Bookwormish-ness runs in our family. Over the generations it has seized the soul of my mother, me, my daughter, and my daughter’s elder daughter, to name just the female victims. For example, whenever I take the subway with my young granddaughters–which is often, and often from one end of Manhattan to the other–I read aloud to them. Nearby passengers listen, smiling. Occasionally one of them says, “I remember that book from when I was a child.”

There is nothing like a book. Nothing. People complain about standing in that endless line at the post office or curse the tedium of their daily train commute from suburb to city and back again. Such frustrating situations can be averted by always (always!) having a book with you. Why wallow in boredom when you can simply transport yourself into another world?

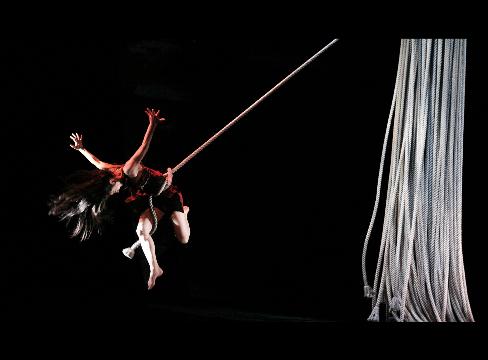

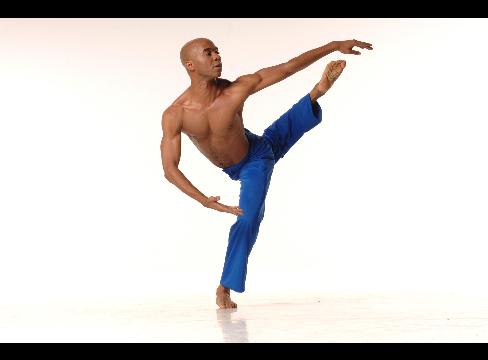

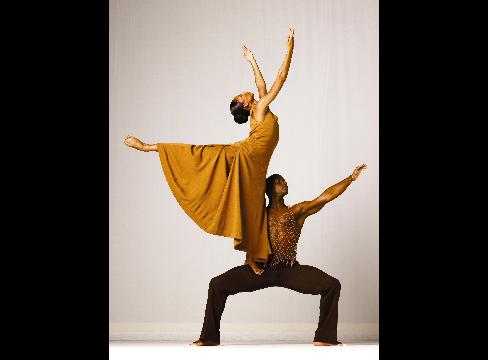

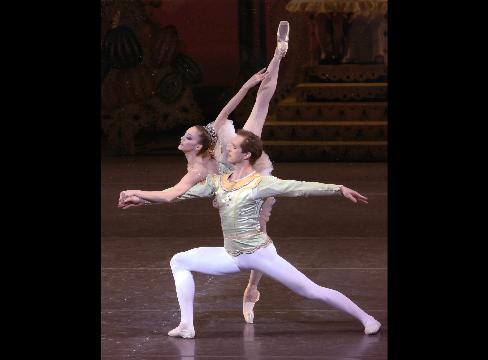

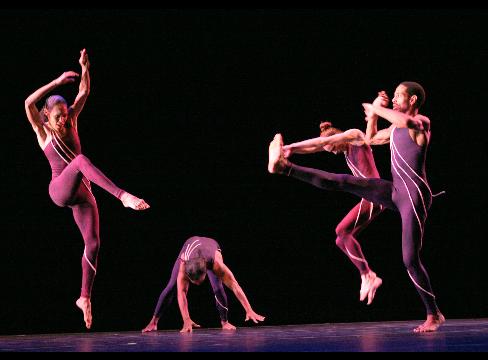

Arthur Mitchell, whose Standard English is meticulous, uses Black English to thrust a point home when the occasion or the audience will benefit from it. Back in the seventies, when he founded Dance Theatre of Harlem, a black classical-dance company–literally taking children off the street to make dancers out of them, as well as teaching them to speak, act, and dress with an elegance that made them royal ambassadors–he’d say, in the accent of his native Harlem, “If I ever catch you in the subway without a book in front of your face . . . .” The sentence was never finished but the implied threat was dire and effective.

I have no idea if young DTH aspirants are still subject to that rule but, when I was teaching dance writing at Barnard College, I used it with my students. I explained to them that their “subway book” had to be one they weren’t required to read but, rather, chose to read, and I offered to buy books for any whose budget couldn’t support the strain. Then, every few sessions of our weekly seminar, I’d require them to whip out their book of the moment and hold it aloft.

I also mentioned regularly that the activities most likely to contribute to one’s becoming a professional writer were, first and foremost, to write a lot and, a close second, to read a lot. To my mind, taking courses in writing counted for nothing compared to learning from the examples of successful practitioners, from the pros who constituted the canon to purveyors of popular junk. Without realizing it at the time, I must have constantly mentioned many books that I loved and that had influenced my work.

The proof: Press tickets, a perk of performance journalists, usually come in pairs, and I regularly shared mine with my students. Occasionally, a dance company performing outside the usual Manhattan precincts would send a bus to collect journalists at Lincoln Center and deliver them to the outlying district in question by curtain time. Journalists were told the appointed hour of the bus’s departure and understood that it would be strictly adhered to. One day I sat in a crowded press bus fuming because my student “date,” who was usually reliable to a fault (scatterbrained conduct was simply not in her rep), had not shown up. Just as the doors of the bus were about to close for the trip, she staggered down the aisle to the empty seat beside me, lugging two outsize, bulging shopping bags emblazoned with the name of a familiar bookstore. “I’m sorry,” she said, close to tears, “I was buying every book you mentioned all semester, and it took longer than I expected.” I expected that, in the course of the next year, she would read them all. She was, as I said, reliable.

Obviously, I consider the acquisition of books a commendable enterprise. It is equally a serious problem. As every obsessive reader knows, books multiply in the night, and you soon find they are taking over your living space to a degree that can be outright dangerous. I remember that Edward Gorey, the inimitable author/artist, having filled his many bookshelves, took to creating tall, rickety, freestanding pillars of subsequently amassed volumes without which, apparently, he could not exist. Once, when I visited my dear friend the novelist Lynne Sharon Schwartz, she had ruthlessly plucked some 150 books from her overladen shelves and set them, spines up for easy identification, in cartons outside her apartment door. In front of them she had placed a boldly lettered sign: “TAKE AS MANY AS YOU WANT.” I’m afraid I did. She offered me some shopping bags with a gleeful smile.

None of the solutions to holding the book invasion at bay are particularly satisfactory, though they may fend off a bibliophile’s anxiety for a while. First of all, one can recognize the fact that book-owning isn’t what it used to be. The books you buy these days, alas, self-destruct at headlong speed–sometimes the spines crack even on the first reading–so amassing a personal library for posterity isn’t even possible. My grandchildren have pored over many of the picture books I originally bought for my children–volumes that are well worn from loving but incessant handling, yet still intact. The new books the grands acquire, however, will surely have collapsed long before their own children arrive on the scene.

As for me, after decades I got tired of using crammed bookshelves as wallpaper. I was never going to read Spinoza or Mickey Spillane–much as I thought I should when I acquired their works–so out they went, along with dozens of other worthy titles that had failed, over time, to seduce me. I felt little guilt about their afterlife. I live in a row house on the Upper West Side; any book put out on my stoop is adopted in ten minutes flat.

At the same time as I deaccessioned, I rediscovered the New York Public Library. Its catalogue is online. In the dead of night, your other chores finally done, you can order any volume in the entire city’s circulating collection to be sent to your local branch. You will be notified by e-mail when it arrives there. Then, all you have to do is stroll over with your library card (surely the ticket to a world of wonders!) and pick it up. If you’re a slow reader, you can renew the book online, more than once if no one else is clamoring for it. The most beautiful thing about the arrangement, though, is that the library makes these books go away–indeed, demands them back, threatening the dilatory with daily, if modest, fines. So now I can, theoretically at least, limit the books I give houseroom to the ones I need and the ones I love. Admittedly, I still have thousands.

I have also become a devotee of the adult version of being read to–audiobooks. While I’m allergic to electronic devices and congenitally incapable of understanding them, my husband, like many another man, is addicted to them. He has helped me acquire the spoken texts (there are several ways to do this without paying a cent, and even more choices if you have funds to spare), get them onto a tiny, portable gizmo that will play them (an iPod or other MP3 player) as I’m moving around, and learn the basic instructions for transferring word to ear–nothing fancy, mind you, like replaying a short section so admirable it begs to be repeated, just the essentials.

Now, when I do my regulation thirty minutes on the gym’s Treadmill to Nowhere or perform routine household tasks–both occasions, for me, of excruciating boredom–I can hear stories. In the last two months, I’ve heard Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting, and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night. (That’s a lot of listening hours, but I have a streak of fitness fanaticism and I do a considerable amount of housework. I even iron, like Balanchine.) True, hearing a book is not really the same as reading the text, just as, between close friends, an e-mail lacks the texture of a letter. But, providing me with a way to elevate my heart rate without going out of my mind, audiobooks are on my short list of admirable contemporary inventions.

And then, just so you know, for books you can read without turning a page (though you do have to stay parked in front of a computer), there’s Project Gutenberg, which provides thousands of works in the public domain. Granted, people who detest reading literature from a screen will hate this. The same folks, however, may be happy to know that pillars of bookdom–the Bible, Shakespeare–are readily accessible on the Internet and yield to keyword searches, a convenience that can’t be claimed by our personally owned (perhaps inherited) bricks-and-mortar copies, though these are laden with other values, sentiment among them.

Valéry-Nicolas Larbaud called his two volumes of literary criticism Ce vice impuni, la lecture (reading, that unpunished vice). Vice only in the secret, all-pervasive delight it can bring, I’d say, along with the haunting fact that the addicted can’t be cured of it. My friend Lynne has, finally, given up smoking, but would never consider giving up books, indeed would never be able to. Nor would I. Nor would my granddaughter Lili, who since she was seven, has marched down the street holding her current book open in front of her face, ignoring her elders’ admonitions about the danger of accident, her very being enraptured by story. Reading may be marred by minor inconveniences, as stated above, along with possible solutions. Still, as I’ve mentioned, there is simply nothing like it. Nothing.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias