It’s summer, the lazy season, and dancing, which never rests, has taken to outdoor venues.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on July 30, 2008. To read it, click here.

Tobi Tobias on Dance et al.

by Tobi Tobias

It’s summer, the lazy season, and dancing, which never rests, has taken to outdoor venues.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on July 30, 2008. To read it, click here.

by Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on July 19, 2008.

Helen Pickett as Agnes, top, and Jim De Block as Mr. Pnut take part in the Royal Ballet of Flanders production of “Impressing the Czar” on Nov. 22, 2005. The ballet, created by William Forsythe in 1988, will be performed by the Royal Ballet of Flanders at the Rose Theater in New York as part of the Lincoln Center Festival through July 20, 2008. Photographer: Johan Persson/Royal Ballet of Flanders via Bloomberg News

July 19 (Bloomberg) — Imagine an evening-length ballet with two unfathomable sections of pretentious chaos and frenzy surrounding an oasis of logic and calm.

That’s “Impressing the Czar,” created by William Forsythe in 1988 for Ballett Frankfurt, reconstructed by the Royal Ballet of Flanders in 2005 and now brought by that troupe to Manhattan’s Rose Theater, where it runs through tomorrow as part of the Lincoln Center Festival.

Acts I and III are busy and loud, jam-packed with action and lacking in sense but crammed full of stuff: people rushing about to a foolish mix of music; raucous, often patently silly, spoken text; a conglomeration of dance styles, ballet basics predominating; gold-painted props portentously exuding ambiguous meanings; gorgeous or outlandish clothes inspired by different locales and times.

What is Forsythe trying to tell us? In Act I, that past eras of art are rich in treasures but that we’re poor custodians of them, treating them as if they were interchangeable parts of the present moment? In Act III, that the culture, in which everything is for sale, has gone to hell in a hand basket? Your guess is as good as mine, probably better; I have little patience for highbrow shenanigans.

The second of the ballet’s three acts, “In the Middle, somewhat elevated,” has nine dancers in practice clothes, a pair of golden cherries hanging above them, execute an abstract work that Forsythe made for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1987. The next year it became the centerpiece of “Czar” and is now danced on its own by several distinguished classical companies.

Cool Chic

Although the Flanders performers are earthier, less finely honed than the Paris crowd, you can still see the cool chic of the choreography. There’s no postmodern froufrou here; Forsythe relies on the intricacies and beauties of more complex classical steps and on form and pattern, mingled judiciously with pedestrian actions like strolling, running and just hanging out, watching. It did him a world of good.

Aki Saito stood out in this section, her movement now like the slice of a lethally sharp knife, now melting like chocolate in the sun.

The inordinately ambitious choreographer is trying to do three things in “Impressing the Czar.” Not content with emulating Balanchine with “In the Middle,” he wants to outdo him. Balanchine took Marius Petipa’s 19th-century achievement forward, building from it — and from his own genius — ballets that would define classical dance in the 20th century and beyond.

No Balanchine

Forsythe, certainly a talent though hardly on the scale of Balanchine, wants to be the man who revitalizes the genre for the 21st century. Yet his deconstruction of the technique he’s inherited from his role model remains theoretical — handsome enough but devoid of feeling.

In the first and final acts, Forsythe wants to indulge his interest in art and architecture, which is keen, tasteful, even imaginative — though it often overwhelms the movement. He also seems to think that if spectators fail to be impressed by the intellectual underpinning he claims for his choreography, they’ll find some thrills in the gaudy chaos and violence to which he gives full rein in this rule-breaking extravaganza.

It’s easy to see that these aims are incompatible.

At the Rose Theater, Broadway at West 60th Street; +1-212-721-6500; http://www.lincolncenter.org.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

by Tobi Tobias

Noche Flamenca

Theater 80, 80 St. Mark’s Place, NYC / July 9-August 12, 2008

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on July 15, 2008. To read it, click here.

by Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on July 7, 2008.

Noah Vinson and Maile Okamura dance during a rehearsal of Mark Morris’ “Romeo & Juliet, On Motifs of Shakespeare,” in New York, on June 11, 2008. Photographer: Johan Henckens/Mark Morris Dance Group via Bloomberg News

July 7 (Bloomberg) — Leave it to Mark Morris to create a “Romeo and Juliet” danced to Prokofiev that features no balcony, no crypt, no pointe work, plenty of passion and violence, yet no final tragedy. The lovers simply move on to some higher plane, enveloped in a star-studded sky.

Morris, 51, is fanatically committed to presenting his dances with live music, so it’s only fitting that this celebrated and controversial choreographer should be the first ever to use Prokofiev’s recently recovered original score for the world premiere of “Romeo and Juliet, On Motifs of Shakespeare” as part of Bard College’s Summerscape Festival.

Material for the reconstruction of the score was recently discovered in a Moscow archive by musicologist Simon Morrison. This original version, occasionally dissonant and rhythmically complex, was intended to show passionate youth challenging feudal conventions about marriage and family. (The blissful-end narrative was worked out with the experimental theater director Sergey Radlov.) It was barred from production by both the Soviet regime and ballet community beginning in 1935.

Desperate to see his work staged, Prokofiev resigned himself in 1940 to a more bombastic and melodramatic alternative, now familiar to dance fans from productions by the Kirov Ballet’s Leonid Lavrovsky, then by John Cranko, Kenneth MacMillan and Frederick Ashton, to name a few.

Homemade Air

The production at Bard, in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, uses the original music and offers many aspects of enchantment, though it hardly eclipses MacMillan’s pull-out-the-stops extravaganza. Morris’s version is tastefully small — fewer than 20 dancers and a single set — and captures the beguiling, homemade air of talented kids putting on a show.

It also relinquishes class distinctions to a great degree. Juliet’s parents, for example, mingle with the throngs in the town square as friendly neighbors of women who don’t even own shoes. The human intimacy of the whole affair is well matched to Bard’s exquisitely proportioned, 500-seat Richard B. Fisher Center for the

Performing Arts.

The choreography mixes a rather thin ballet vocabulary with robust modern dance and folk touches and lusty, centuries-old Italian mime — a typical Morris blend. One of the best elements of the production, rare for this choreographer, is the detail with which the principals reflect the most fleeting emotion.

Tender Romeo

Rita Donahue as Juliet goes from the touching confusion of an inexperienced teen making her social debut to incredulous delight in David Leventhal’s Romeo, who has crashed the party. Leventhal, whose initial reticence is wimpy, gains confidence by quick degrees from Juliet’s response, assuring us (and her) that he will always treat her tenderly. This is fortunate because, in a unique interpretation, Bradon McDonald’s Paris, the suitor with the senior Capulets’ approval, acts as if he owns the girl, repelling her with his rough handling.

Lauren Grant is terrific as the Nurse (more of a multipurpose servant who participates in all of the family’s affairs). As Prince Escalus, Joe Bowie’s putting down the latest melee in the Capulet-Montague feud was my favorite passage. Resplendent in the black and gold of his authority, he faces the crowd in the blood-soaked town square and, with grave, calm gestures, preaches that reconciliation is the only path to peace.

The gender switch in the casting of Amber Darragh as Mercutio and Julie Worden as Tybalt was fun yet unconvincing. The biggest disappointment was the quartet of senior dancers — now retired from the company, though some of the most memorable artists it has ever had — summoned back to play the Capulet and Montague parents. Three had nothing meaningful to do; the fourth seemed not to include dramatic imagination among her gifts.

Leon Botstein conducted the American Symphony Orchestra in a sensitive reading of the score. Allen Moyer contributed handsome, clever scenery with a childlike air, raw-looking wood prevailing from swords to miniature houses representing Verona. Martin Pakledinaz was at less than his personal best with the costumes.

Mark Morris Dance Group and American Symphony Orchestra perform “Romeo and Juliet, On Motifs of Shakespeare” through July 9 at Bard Summerscape Festival, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. Information: +1-845-758-7926; http://summerscape.bard.edu.

The $1.1 million production will travel to Berkeley, California, Sept. 25-28; London, Nov. 5-8; Urbana, Illinois, March 13-14; Norfolk, Virginia, May 8-10; New York’s Lincoln Center, May 14-17; and Chicago, September 2009.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

by Tobi Tobias

Compagnie Maguy Marin: Umwelt

Joyce Theater, NYC / June 17-22, 2008

Compagnie Maguy Marin in Maguy Marin’s Umwelt. Photo by Ganet.

Commentators claim that Marin, inspired by Samuel Beckett, considers the actions banal and underlines that quality by reiterating them obsessively. I suspect she has a trick card up her sleeve. They certainly don’t look banal to me; I think they take on an epic radiance. I’d guess that Marin is observing the everyday world and saying “Wow! Just look at that!”

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on June 24, 2008. To read it, click here.

by Tobi Tobias

I am in Paris with my husband. I have convinced him that he wants to accompany me to one of the city’s legendary flea markets. It is way, way out on the edge of town, a lengthy pilgrimage on the Métro, past stops with names like La Fourche (the fork, as in a road, which it is), Montparnasse-Bienvenüe, Gaîté, Plaisance. Eventually we arrive.

I shop; he watches. After nearly two hours of this, even I–the indefatigable seeker after the old and unusual–get tired. We exit and collapse onto the low, narrow concrete ledge in which the hefty chain-link fence that separates the market from ordinary life has been embedded.

We are both exhausted and the sun is turning brutal. What’s more, we’re both hungry, a state that can lead to cranky in a matter of minutes. (Has anyone ever studied the effect of low blood sugar on intimate human relationships?) The two of us sit there gathering strength for our next move, which should be lunch–a croque monsieur and a beer, say, if we can find a café that’s not too seedy. Meanwhile, my husband has closed his eyes and retreated into the semi-comatose state of men haplessly extended beyond their tolerance.

Suddenly, some 200 yards away, I see a woman walking toward the market. She’s nibbling on something she holds in her hand. If we were in the States, I’d assume, from the look of the thing, that it was a hotdog roll. But we are not in the States. We are in the land called Delicious.

As the woman comes nearer, I realize that it’s pastry she’s holding. Even nearer: Pastry of a lightness and flakiness that are the province of French baking. Very close, just about to pass us: The sublime pastry is coated on top with a gleaming stripe of icing the color of café au lait and filled with a silky-looking cream a shade paler.

“Come on, come on,” I say to rouse my somnolent husband. I’m standing now, tugging at his hand, pulling him to his feet. “A coffee éclair! It looked fabulous! We’ll just walk in the direction she came from,” I urge, pointing to the woman now visible to us only from the back. “The bakery can’t be far away.” And it isn’t. Just about two and half blocks.

“How do you know these things?” my husband asks wearily, as if his question were rhetorical.

“I know everything about things like coffee éclairs,” I reply with considerable–if somewhat defensive–dignity. I may not know much about math or science, but I do know literature and dancing and coffee éclairs.” (I choose not to reveal to my husband that, as an Agatha Christie addict, I’ve deduced that the point of purchase must have been close enough for the pastry not to have been fully consumed when the woman passed us.) My husband just shakes his head as we enter the fragrant shop.

Since I’m in charge of French in our marriage, I do the ordering: a coffee éclair for me, a chocolate éclair for him. He dislikes coffee, but I knew chocolate would be available, it being the default mode for éclairs. He pays. He understands foreign money. When I’m alone, I just cross my own palm abundantly with silver and extend it to the seller, hoping he’s honest.

Not surprisingly, this is the most delectable éclair I have ever tasted. And it continues, in memory, to hold first place to this day, despite the passing of so many tastings and so many decades.

© 2008 Tobi Tobias

by Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on June 20, 2008.

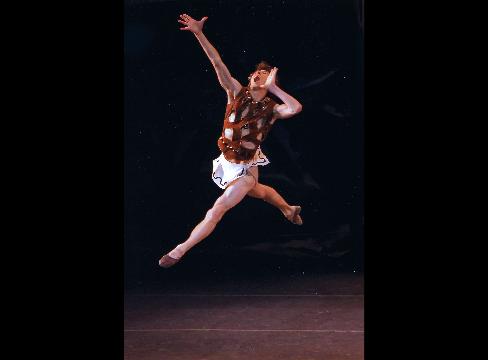

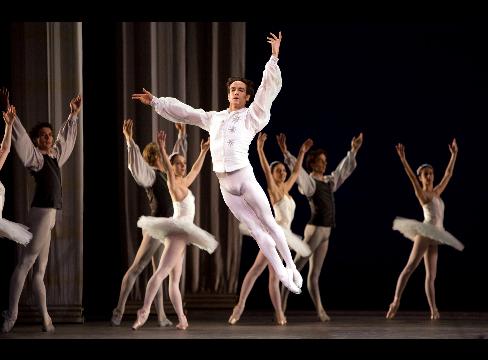

Damian Woetzel dances in “Prodigal Son (Ballet in Three Scenes)” during his farewell performance with the New York City Ballet at the New York State Theatre at Lincoln Center in New York on June 18, 2008. Woetzel has danced with the NYCB to continual acclaim for 23 years, 19 of them as a principal. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

June 20 (Bloomberg) — Damian Woetzel has danced with the New York City Ballet to continual acclaim for 23 years, 19 of them as a principal. Wednesday night, at Lincoln Center’s New York State Theater, the 41-year-old gave his farewell performance with the company, thus taking the decisive next step into his future.

Not, however, before both his colleagues and his fans treated him to ovations, bouquets and a shower of confetti that seemed to go on and on, as if doing so would keep the night from ending.

Woetzel belongs to the type best exemplified by Edward Villella — a regular American guy, tough and likable, with craggy good looks and no fancy airs about him. When virtuosity is called for, he makes it look free and easy. When drama is needed, he projects emotions that are intense and true.

A natural for Jerome Robbins’s work, which was what drew him to City Ballet in the first place, Woetzel chose to retire in the company’s season-long celebration of the late choreographer on the 90th anniversary of his birth.

Dancers, from left, Joaquin de Luz, Tyler Angle, and Damian Woetzel take part in a performance of “Fancy Free” during Woetzel’s farewell performance with the New York City Ballet at the New York State Theatre at Lincoln Center in New York on June 18, 2008. Woetzel has danced with the NYCB to continual acclaim for 23 years, 19 of them as a principal. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

For his last performance Woetzel appeared in “Fancy Free,” the ballet about three sailors on shore leave in New York that put Robbins on the map in 1944 and remains an audience favorite. He danced the role Robbins himself originated — the guy with a way of seducing girls with his war stories and slinky rumba. His performance — every move seemingly colloquial — was a perfect expression of his blithe naturalness, his sense of humor, his sheer pleasure in dancing.

`Prodigal Son’

Of course he performed a landmark George Balanchine work as well. In the 1929 biblically based “Prodigal Son,” Woetzel plays a rebellious adolescent who learns humility, respect and love only after leaving home for the freedom of a hellish world. Woetzel’s searing encounters with wild drinking, demonic sex and being stripped of everything he owns are capped by his return, bruised, filthy and crawling on his knees into his father’s forgiving embrace. Every scene revealed his ability to make a ballet look newborn, and his pathos in the final passages was the most poignant I’ve ever witnessed.

At the end of the show — which included Balanchine’s “Rubies,” with Woetzel, partnering Yvonne Borree, making a surprise appearance — the packed house stood, clapping and cheering (as they had for “Fancy Free”). One by one, a bevy of principal dancers, some from friendly rival troupes, presented him with lush bouquets.

Glittering Confetti

Dancer Damian Woetzel, on center stage, bows to the crowd after his farewell performance with the New York City Ballet at the New York State Theatre at Lincoln Center in New York on June 18, 2008. Woetzel has danced with the NYCB to continual acclaim for 23 years, 19 of them as a principal. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

The rest of his colleagues joined the onstage crowd to applaud him while company director Peter Martins signaled for a shower of glittering confetti to fall from above. Audience members hurled their own floral tributes over the heads of the orchestra, refusing to go home even when the house lights went up.

The hoopla was not simply conventional. Woetzel has earned not just his fans’ admiration but their love. You don’t have to know the man personally to sense his intelligence and integrity; it glows through his dancing.

What’s next? In tandem with the last years of his performing career, Woetzel earned a master’s degree in Public Administration at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government — accepted though he’d never been to college — and won acclaim as the new artistic director of the Vail International Dance Festival.

With the sensibility he’s developed as a dancer combined with the administrative know-how he’s acquiring, Woetzel seems a likely successor to Martins. He’s already indicated to the press that he’d be very interested in the job — when the time comes.

The New York City Ballet continues through June 29 at Lincoln Center, Broadway at 65th St. Information: +1-212-721-6500; http://www.nycballet.org.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

by Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on June 9, 2008.

June 9 (Bloomberg) — Alexei Ratmansky’s “Concerto DSCH,” by far the most exciting new ballet I’ve seen in ages, had its world premiere last week in the New York City Ballet’s spring season at Lincoln Center. At first it looks like a mere romp — Jazz Age youth cavorting on the beach — but almost immediately its unflaggingly deft and original construction becomes apparent.

Taking its title from its score, Dimitri Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto, the ballet sets in motion a clear cast of characters, without getting bogged down in introducing them formally. Ratmansky arranges the action so ingeniously that the viewer can identify them even as the dance hurtles on.

Wendy Whelan (a cool mermaid) and Benjamin Millepied (her hopelessly ardent swain) provide fleeting summer romance; virtuosi Ashley Bouder, Joaquin De Luz and Gonzalo Garcia are like rough-and-tumble saltimbanques on speed. The 14-member ensemble, creating whirlwinds as a whole, also fractures into smaller units to serve as demi-soloists.

The marvel of the choreography is that the groupings keep combining and recombining, often very unusually placed on the stage. Ratmansky’s virtues don’t stop here. His choreography concerns itself with people, not just dancers and their phenomenal physicality.

Crouching God

He knows ballet history and uses it with wit, making a bow to the house he’s working in, for example, by extending the “swimming lesson” of Balanchine’s “Apollo”: When the god crouches to float Terpsichore on his back, he walks her into the wings in that position. Most charmingly, the lovers’ inevitable farewell echoes the separation of child hero and heroine at the end of the Christmas Eve party in

Balanchine’s “Nutcracker.”

Earlier this year, Ratmansky said he planned to resign as artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet in order to devote himself to choreography. His work, accomplished and fresh, is much in demand from world-class companies. City Ballet was considering him as a replacement for company choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, but the arrangement fell through. “Concerto DSCH” suggests it’s time for the proposition to be reconsidered.

Meanwhile City Ballet continues its season-long celebration of Jerome Robbins. So far, the incontestable highlight has been “Definitive Chopin,” a program offering three ballets with music by the composer to whom Robbins repeatedly returned.

Teasing Gaiety

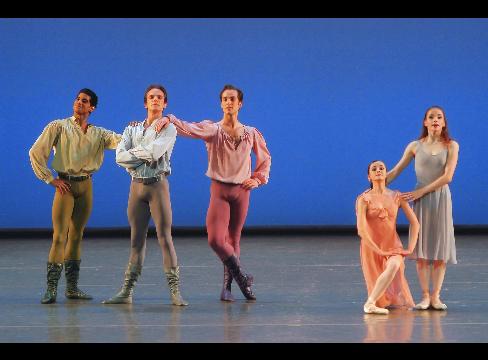

Dancers, from left, Yvonne Borree, Rachel Rutherford, and Abi Stafford perform in the New York City Ballet production “Dances at a Gathering” in New York on May 27, 2007. Performances of the present production continue through June 29, 2008 at the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

The main entry is the 1969 “Dances at a Gathering,” in which the young people of a rural community bond with one another and with the land that is their home. Contentment, a teasing gaiety, emotionally stormy weather tempered by reconciliation, the qualified acceptance of a newcomer among them — all are tinged with unclouded optimism, undercut by just one tableau that hints at the approaching destruction of war.

The present production is the most technically polished and musically sensitive I’ve seen since the premiere, which was buoyed by charismatic stars — Edward Villella, Patricia McBride and Violette Verdy — who have no equivalent in the company today. Most impressive among the 10 dancers were the radiantly girlish Rachel Rutherford, who was in her element and projected the deepest feeling among the group, and Sara Mearns, who played the flirtatious odd girl out on her own terms.

Dancers, from left, Amar Ramasar, Jonathan Stafford, Jared Angle, Yvonne Borree, and Abi Stafford perform in the New York City Ballet production “Dances at a Gathering” in New York, on May 27, 2007. Performances of the present production continue through June 29, 2008 at the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

“Other Dances,” created in 1976 for Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov, has deservedly become a keeper, performed by many stellar successors. Mainly lyrical in mood, it’s inflected with middle-European folk-dance motifs, as if to remind us of where the composer came from. It’s not a romantic duet but something more remarkable — an illustration of the intimacy dancers forge with each other through the act of dancing.

Poetic to Absurd

This time out, Damian Woetzel, who retires from the City Ballet this season, partnered Julie Kent, a senior American Ballet Theater ballerina. Woetzel brought all his gifts to the occasion: virtuosic technical command, astute, gracious partnering, keen intelligence and craggy good looks. Kent, all ethereal delicacy, melted in his arms.

“The Concert” (1956) is that welcome rarity, a successful funny ballet. It depicts the reveries, from poetic to absurd, of the concert-hall audience. Sterling Hyltin, her waist-length wavy blond hair prominent, shone as the production’s ditzy siren, while the jokes about all-too-human types and choreographic discombobulation seemed new once again.

Through June 29 at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, Broadway at 65th St. Information: +1-212-721-6500; http://www.nycballet.org.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

by Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on June 5, 2008.

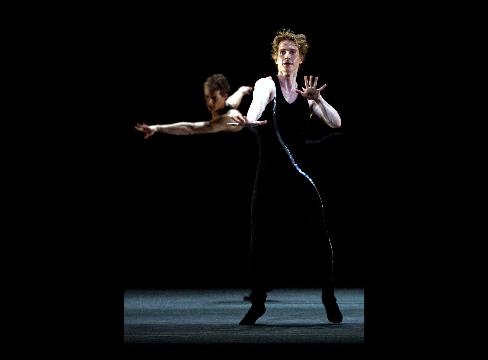

Ethan Stiefel, right, performs in the American Ballet Theatre production of Twyla Tharp’s “Rabbit and Rogue” at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York on June 2, 2008. Performances continue through July 12 at the opera house, part of Manhattan’s Lincoln Center. Photographer: Rosalie O’Connor/ABT via Bloomberg News

June 5 (Bloomberg) — Ethan Stiefel, his Mr. Perfect technique softened since an operation for knee trouble, is the elder brother, all smart-alecky goofiness. Herman Cornejo, a whiz of a dancer, is his competitive kid brother. Driving each other nuts yet irrevocably bonded, the two are the heroes of Twyla Tharp’s “Rabbit and Rogue,” given its world premiere Tuesday night in New York by American Ballet Theatre.

The pair sets out to see the world, accompanied by a colorful mix of music by the film composer Danny Elfman. Well, a postmodern idea of the world: They visit Hell, where Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg, alternately quarreling and making love, are the central patrons of a with-it nightclub where the required dress is black, skimpy and spangled. (Outfits by Norma Kamali.)

Next stop is Heaven, a peaceable kingdom, all white gowns and silver trousers, reigned over by Paloma Herrera and Gennadi Saveliev. In this place, one might find serene compatibility, even true love, perhaps bliss. Then the worlds commingle, as in real life.

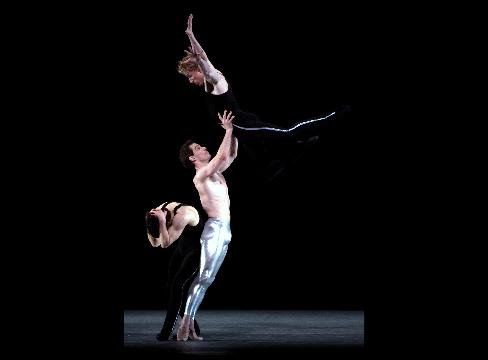

Dancers, from left, Herman Cornejo, Craig Salstein and Ethan Stiefel perform in the American Ballet Theatre production of Twyla Tharp’s “Rabbit and Rogue” at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York on June 2, 2008. Performances continue through July 12 at the opera house, part of Manhattan’s Lincoln Center. Photographer: Rosalie O’Connor/ABT via Bloomberg News

At this point, the ballet begins to feel too long and too diffuse.

The most remarkable thing about the choreography is that most of it travels in horizontal lines from one side of the stage to the other. The dancers look like an adrenalin-infused Greek frieze or simply a view of life’s passing parade. Leave it to Tharp to break one of dance-making’s cardinal rules about variety with deadpan confidence.

Steel-Trap Mind

From conventionally avant-gardish beginnings in the late 1960s, Tharp — with her steel-trap mind, theatrical flair and inordinate ambition — swiftly found her singular mode of combining classical ballet, jazz and vernacular moves. Her choreography has always been rigorous and complex, wittily melding popular with highbrow.

From exquisite pieces that caught the mood of a moment in cultural history, she switched to semi-narrative work that ran on rage. In recent years, she created high-voltage shows for Broadway. “Movin’ Out,” set to Billy Joel songs, had legs; “The Times They Are A-Changin,” to Bob Dylan numbers, was a dud. “Rabbit and Rogue” brings her back to ABT after a long absence. Surprisingly, for she is a great inventor, it doesn’t have much in it that seems new.

`Etudes’

Sascha Radetsky, center, performs in the American Ballet Theatre production of Harald Lander’s “Etudes” at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York on May 19, 2008. Performances continue through July 12 at the opera house, part of Manhattan’s Lincoln Center. Photographer: Rosalie O’Connor/ABT via Bloomberg News

In 1948, Harald Lander created “Etudes” — his best work, I’m afraid — for the Royal Danish Ballet, which he headed. He left the company under unpleasant circumstances a few years later for the Paris Opera Ballet, where he reworked the piece into the souped-up version seen worldwide today. For reasons I can’t fathom, ABT revived its production to accompany the Tharp.

Granted, “Etudes” is a crowd pleaser, but it’s in execrable taste. It purports to show the classical dancer’s training in a nutshell, goes on to hokey incarnations of the contrasting Romantic and Classical periods and climaxes in a series of escalating virtuoso feats performed in intersecting diagonal lines — a situation that titillates the audience with its looming peril.

On the whole, ABT’s dancers performed it with immaculate precision, a mark of commendable technique throughout the ranks. Still, the company might have done better to sacrifice neatness to more fire in the belly.

Through July 12 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, Broadway at 65th Street. Information: +1-212-419-4321; http://www.abt.org.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

by Tobi Tobias

2008 School of American Ballet Workshop Performances

Peter Jay Sharp Theater / Lincoln Center, NYC / May 31 & June 2, 2008

Students of the School of American Ballet in Jock Soto’s Interlude. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

The performers of Jerome Robbins’s “2 & 3 Part Inventions” moved with a graciousness, fluency, and technical prowess you’d hardly expect from aspirants of their tender age. They also have a more than nascent command of style and remarkable stage presence. I was especially taken by Lauren Lovette. She has the grave dignity of a princess without being high and mighty about it.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on June 3, 2008. To read it, click here.

an ArtsJournal blog