Ballet Diary No.9: American Ballet Theatre: All-Classic [Masters] program; ABT Premieres program; Natalia Osipova dancing Juliet in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet (ABT’s season at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC, closed on July 10, 2010)

Note: This is No. 9 in the series “Ballet Diary”–comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4; No. 5; No. 6; No.7; No. 8. The completed “Ballet Diary” series will comprise nine essays.

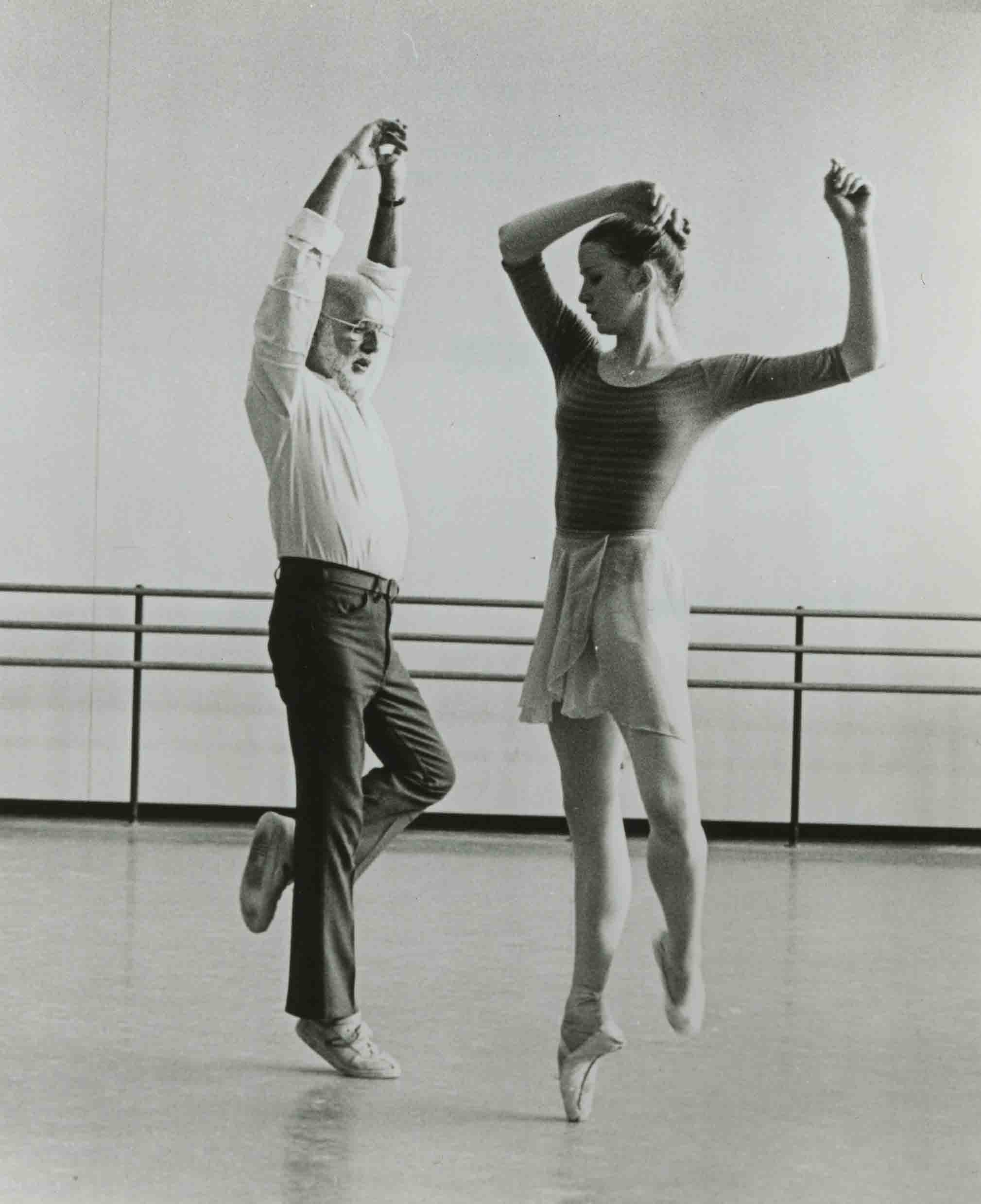

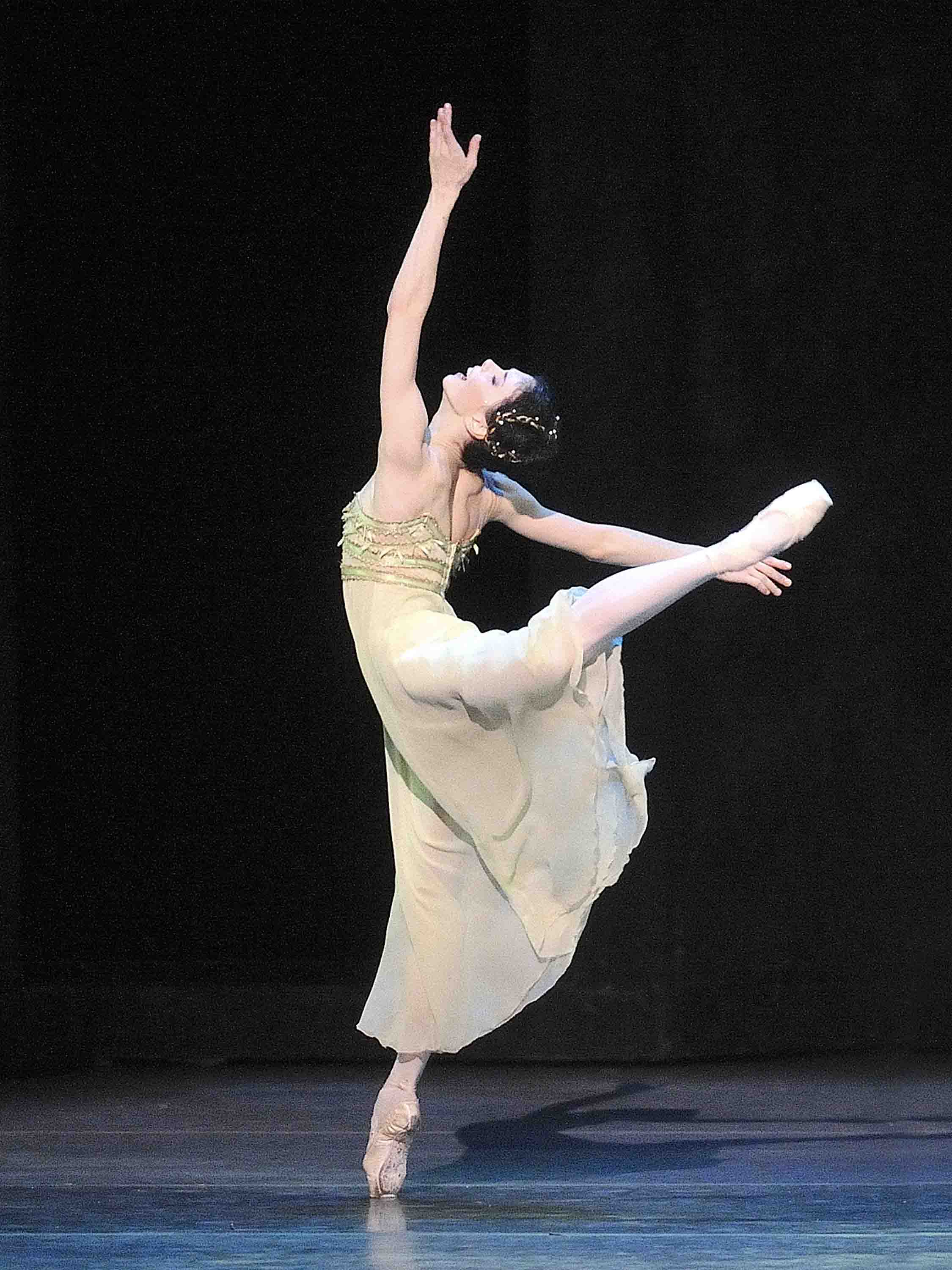

ABT’s Gillian Murphy in Tharp’s Brahms-Haydn Variations

Photo: Gene Schiavone

June has given way to July as I write this and I’m beginning to think I’ve taken up residence at Lincoln Center, along with a dozen or two of my dance writing colleagues. Those camp cots parked in the subterranean corner of the Metropolitan Opera House where you can borrow a booster seat (covered in dark red plush, of course) for a small child you’re introducing to high-end singing and dancing? That’s what we sleep on between one day’s performance and the next. Showers? Did you think those were nymphs and satyrs you glimpsed frolicking in the plaza’s spectacular fountain?

New York City Ballet has finished its eight-week season at the David H. Koch Theater and departed to Saratoga Springs for its annual summer stint, while American Ballet Theatre is in the penultimate week of its eight weeks at the Met.

One of my colleagues asked if, after completing my nine “Ballet Diary” essays on the spring seasons of the two companies, I was going to write a round-up. Well, no. I will already have said all I have to say, but, for anyone who needs a quick condensation, here it is.

Both troupes offered some spectacular dancing–all through the ranks, from newbies to reigning stars. Both companies disappointed when it came to repertory, influenced more by commercial concerns than aesthetic ones. This, despite City Ballet’s proud claim to be an institution bent on producing new choreography to new music–a strategy that regularly yielded fruit only when the new work was by Balanchine and, if you will, Robbins.

City Ballet put a name to its season, “Architecture of Dance,” and commissioned seven new ballets along with five scores, hiring a celebrated architect, Santiago Calatrava, to provide décor. In my view, all this looked more like a marketing ploy than an artistic vision. The results, at any rate, proved to be an artistic failure, since only one of the ballets–Alexei Ratmansky’s Namouna: A Grand Divertissement–is worth keeping. Again in my view, of course, but what other view can I offer?

Ballet Theatre settled for a less fancy, less chancy way of selling tickets: Figure out what the public wants and serve it up, enhanced by stars. This resulted in week-long stints devoted to program-length ballets of varying artistic merit. A couple provided nothing more than easy entertainment (Don Q, for instance, hardly speaks to your soul); another two (Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty) were wretched versions of classical ballet’s 19th-century linchpins. Programs of several shorter works were arranged under titles like “All-Ashton” (which was OK as a demonstration of the company’s faith that here was a topnotch choreographer whose style was worth the effort needed to learn it) and “ABT Premieres” (ballets that had been created on the home team), which was plain silly. After all, to quote Gershwin, who cares?

So the delight to be had at performances lay in a few ballets (Ashton’s Dream, Balanchine’s Symphony in Three Movements, to name two) and in the majority of the nearly 200 dancers the companies harbor between them.

The penultimate week of ABT’s season took me first to what was originally advertised as the All-Classic program. Leaving it to scholars with higher brows than mine to debate what constitutes a classic (well, how about “a work that continues to be compelling after the era in which it was made”?), I can report that the evening–shorn of its title in the house program–was pleasurable in part because the five choreographers represented knew and used their heritage while inventing a world according to their singular vision. Equally important was the fact that the dancing ranged from very good to sublime.

In Balanchine’s 1956 Allegro Brillante (which opens with its eight-member ensemble already circling the stage at a run), Gillian Murphy, dancing the female lead, embodied the speed and dazzle the ballet’s title promises. “It contains everything I know about the classical ballet in 13 minutes,” Balanchine said of the piece, and Murphy met and luxuriated in its challenges.

Acting Becomes Her: Xiomara Reyes and Gennadi Saveliev in Tudor’s Romeo and Juliet

Photo: MIRO

A scene choreographed by Antony Tudor, tactfully termed “Romeo’s Farewell to Juliet” (it’s the aftermath of the young lovers’ wedding night), conjured up memories of the most wonderful Romeo and Juliet of them all–Tudor’s one-act version, created in 1943 and set to music by Delius. As a vehicle for Xiomara Reyes, the least compelling of ABT’s ballerinas, the piece is a godsend. Reyes, who is belatedly adding drama to her dancing, lends herself to the demands of the choreography from the first moment. With Romeo still asleep in her bed, Juliet sits up and strokes the inside of one thigh, remembering, then moves toward the early light streaming into the room and shields her face from it, knowing that her new husband, exiled for murder, must leave her with the coming of dawn. Tudor makes every gesture in the pair’s plangent interaction not simply a dance move but a phrase spoken–about a love that both partners fear will be lost to death.

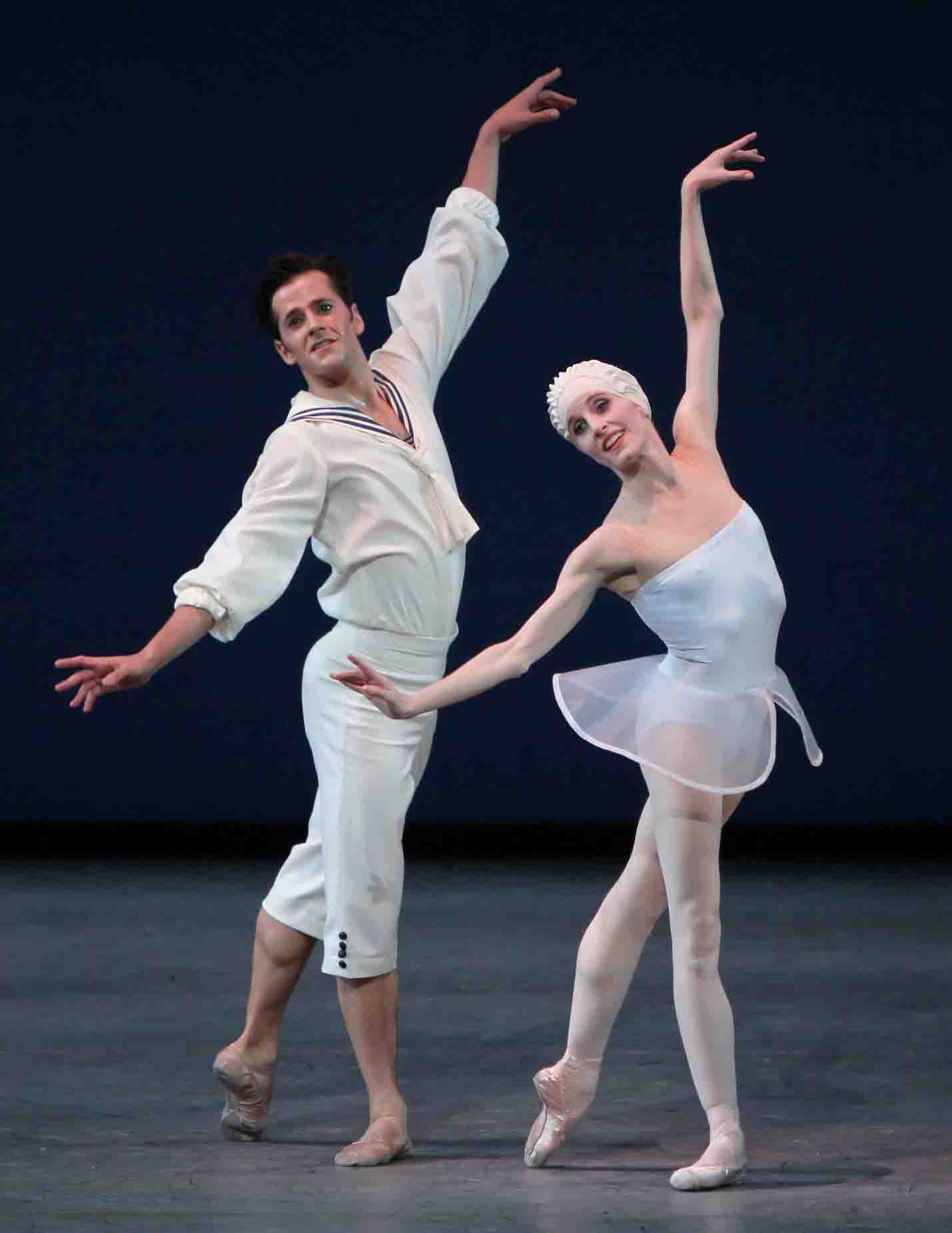

Another Point of View: Hee Seo and Sascha Radetsky in Ashton’s Thaïs Pas de Deux

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Earlier I wrote about Ashton’s evocative Thaïs Pas de Deux, with Diana Vishneva’s being about as good as it gets in the musk-scented title role. Now I’ve seen Hee Seo making her debut in the part. Seo’s a corps de ballet dancer who has lately been fed one prominent role after another. (Note: On July 6, ABT announced–to no one’s surprise–that Seo would be promoted to soloist rank in August.) She has a soft dewy quality, astonishingly beautiful feet, and formidable technique that was coupled in the Thaïs duet with the modest demeanor of a dancer who doesn’t yet “own” the choreography. It seems that, with this piece, made in 1971, Ashton created a situation in which sensuousness can be conveyed in markedly different ways.

On the same program, Vishneva, sympathetically partnered by Jose Manuel Carreño, danced the Act I pas de deux from Kenneth MacMillan’s 1974 Manon. Her portrayal had just the right mix of girlish love and wanton lust, and she gave a perfect account of the scene’s mounting passion. I’ll never really succumb to MacMillan’s exaggerated (and often morbid) theatricality and his near-obsession with seemingly impossible lifts meant to express the peaks of emotion, but he clearly knows how to excite a large audience to fever pitch, and Vishneva is aptly cast as the ballerina to help him do it.

I also wrote about The Dream earlier this season, when ABT’s best-realized achievement with the Ashton repertory was danced by Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg as Titania and Oberon, Herman Cornejo as Puck, and Julio Bragado-Young as Bottom. At that moment, I couldn’t imagine another American cast doing as well.

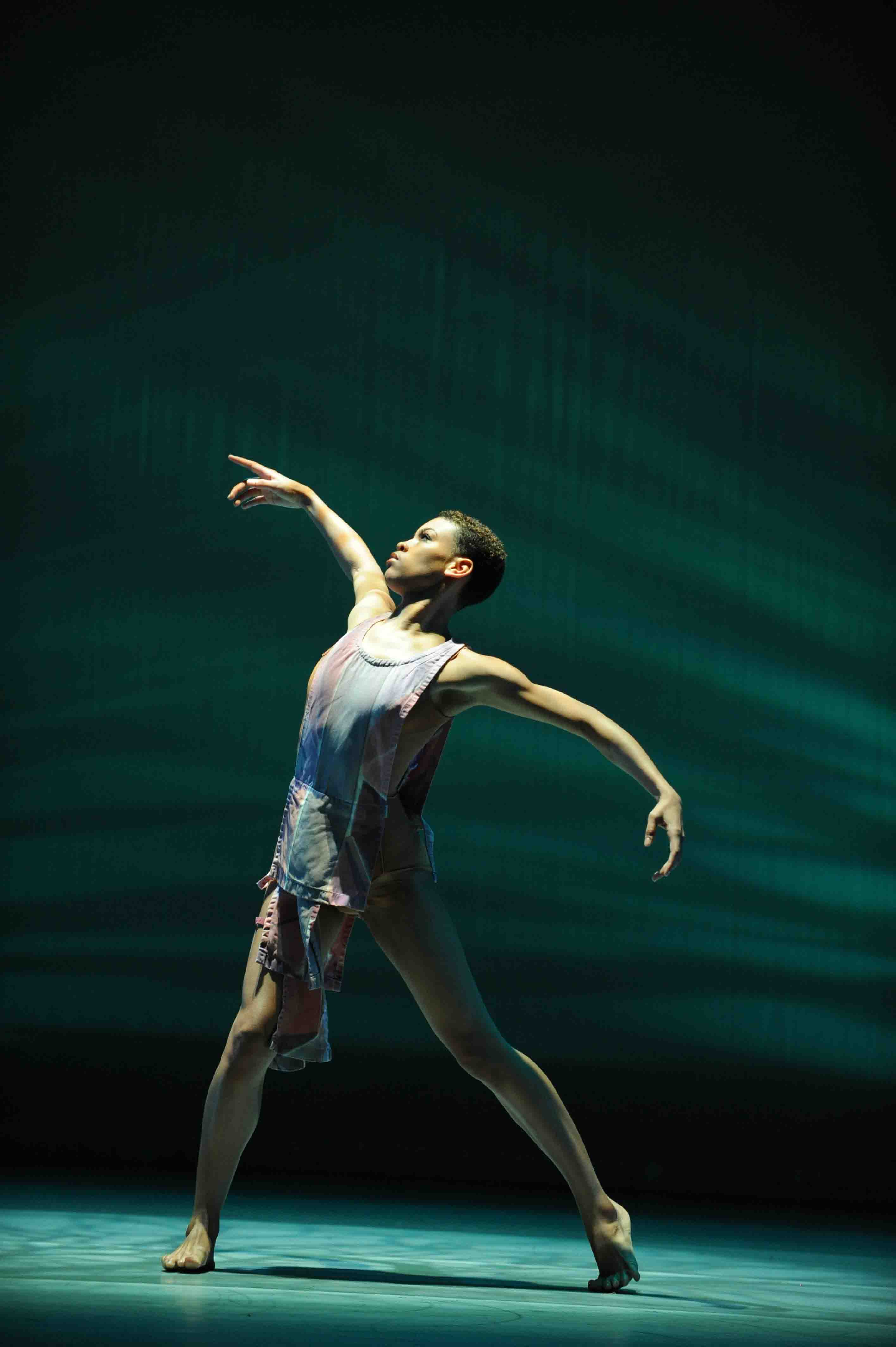

Another Part of the Forest: Julie Kent in Ashton’s Dream

Photo: Gene Schiavone

As it turned out, the team of Julie Kent, Marcello Gomes, Craig Salstein, and Isaac Stappas revealed different dimensions of the choreography. Kent’s rendition of Titania was more conventionally fairylike, given the ballerina’s personal beauty and the delicacy and crispness of her dancing. Gomes’s signature authority was put to splendid use in his interpretation of Oberon. While he couldn’t equal Hallberg’s lightness and fluidity in the role’s pure dance passages, he brought unmatchable clarity and force to the mime. Craig Salstein overplayed the mischief-making Puck with his self-conscious cuteness, but Isaac Stappas gave the most natural–almost Stanislavskian–rendition of the Bottom’s Dream solo that I’ve ever seen. The bevy of fairies scurried more deliciously than ever and the two pairs of human lovers did much to make their botanical drug-induced adventures intelligible in their change-partners-and-dance thread of the plot.

The climactic duet of Titania and Oberon was exquisitely performed. Oberon allows Titania to stray from him thus far and no further, the sequence of release-and-retract moves seeming to occur on the spur of the moment. Soon the partners are twisting and flickering, as if to reveal that they are two of the same breed. Titania runs away (knowingly, not very far) and Oberon pursues her, both of them visibly aware that she has no plans to go astray. And, indeed, she soon flies, literally, into his arms. He supports her at arm’s length as she darts into an arabesque–poised for flight yet again–but then she melts back against his body as if acquiescing to the idea that this is her home. The choreography is tricky, to put it mildly, but Kent and Gomes made it look like a natural extension of their unique dance temperaments.

Panorama: ABT dancers in Tharp’s Brahms-Haydn Variations

Photo: Gene Schiavone

In the same week, I saw the ABT Premieres program. Twyla Tharp’s Brahms-Haydn Variations, created in 2000, was the curtain raiser, as it was for the All-American program, and I wrote about it here. Even so, since there’s always more to see in this ballet, there’s always more to say.

On this showing it was danced with such assurance and calm that its constant contrasts were particularly clear: a pair or two of dancers alternating with a crowd of them, each player confident of his or her place in the choreographic scheme; pure classical form set against impulses that rippled through the entire body, tipped it askew, or turned it upside down; minuscule jokes–about ballet, about myriad ways of dancing, about moving through space in general; celestial harmony juxtaposed with the very different beauty to be found in awkwardness.

Every time I see Brahms-Haydn again, I think that it’s finer than I realized it was the time before. My only quibble with the piece is that it seems too complex to grasp fully on an initial viewing, while because of the hours and dollars that going to the ballet consumes, more spectators than not will be content with a single sighting.

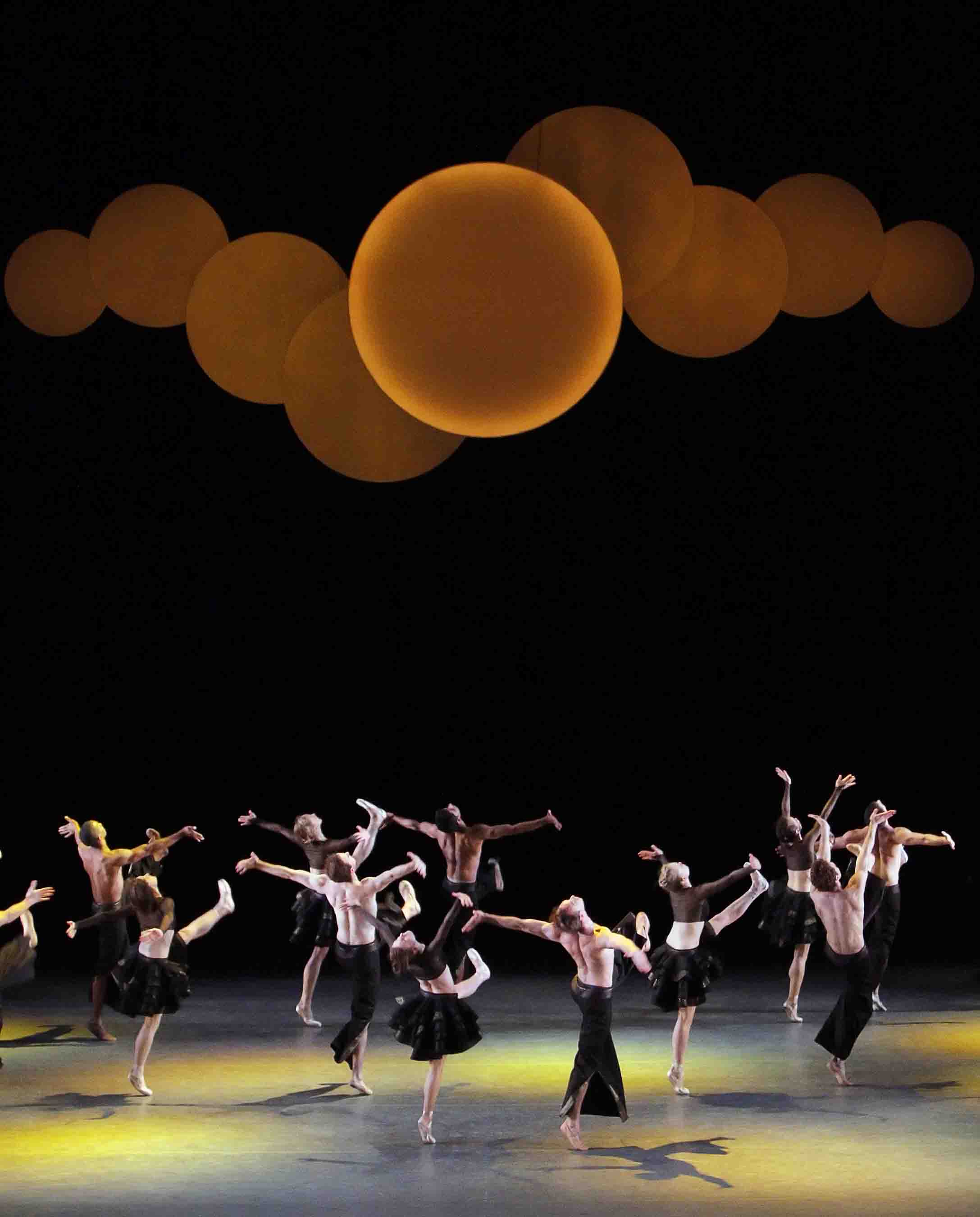

On the Dnieper, made for ABT in 2009 to the eponymous Prokofiev score, is the most deeply Russian of the Alexei Ratmansky ballets that have been performed in the States. Its chief characters–a soldier returning from the front, the fiancée he’s pledged to, and the girl he now finds he wants to marry–are beset by wrenching emotions, and they express them accordingly, like figures in a Dostoevsky novel. In some 40 minutes Ratmansky depicts love, desire refusing to be quelled, confusion, jealousy, regret, selfless resignation–and an unspecific promise of joy.

The choreography is enriched by references–just hints in passing–to landmark Russian ballets, such as the female ensemble’s forming patterns borrowed from Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Noces. Ratmansky is the sort of dance maker who keeps the history of his art in mind and makes it a living element of his own work. Simon Pastukh’s scenery suggests a long-ago rural Russia, a bleak landscape softened by spring’s blooming cherry trees that, all too soon, scatter their petals on the earth.

Late Spring: ABT dancers in Ratmansky’s On the Dnieper

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Having seen and reviewed the first cast of the ballet at its premiere (with Marcelo Gomes as the soldier, Veronika Part as his old love, Paloma Herrera as his new), I chose to see the second cast this season. Gomes remains irreplaceable, but Maria Riccetto, whom I’ve always thought of as a dry, inexpressive dancer, blossomed as the fiancée and was truly touching. Simone Messmer was fascinating as the most innocent “other woman” in ballet history except, perhaps, the Sylphide. In every role I’ve seen her perform, she has looked different–and remarkable. Here she made me wonder how ABT thinks of her: as a character dancer? a dramatic dancer? I’m fairly certain she’s not on the tiara-type ballerina track, but, if the company provides intelligent, steady mentoring, might she not become tomorrow’s Nora Kaye? Or, more likely, more fully and clearly herself?

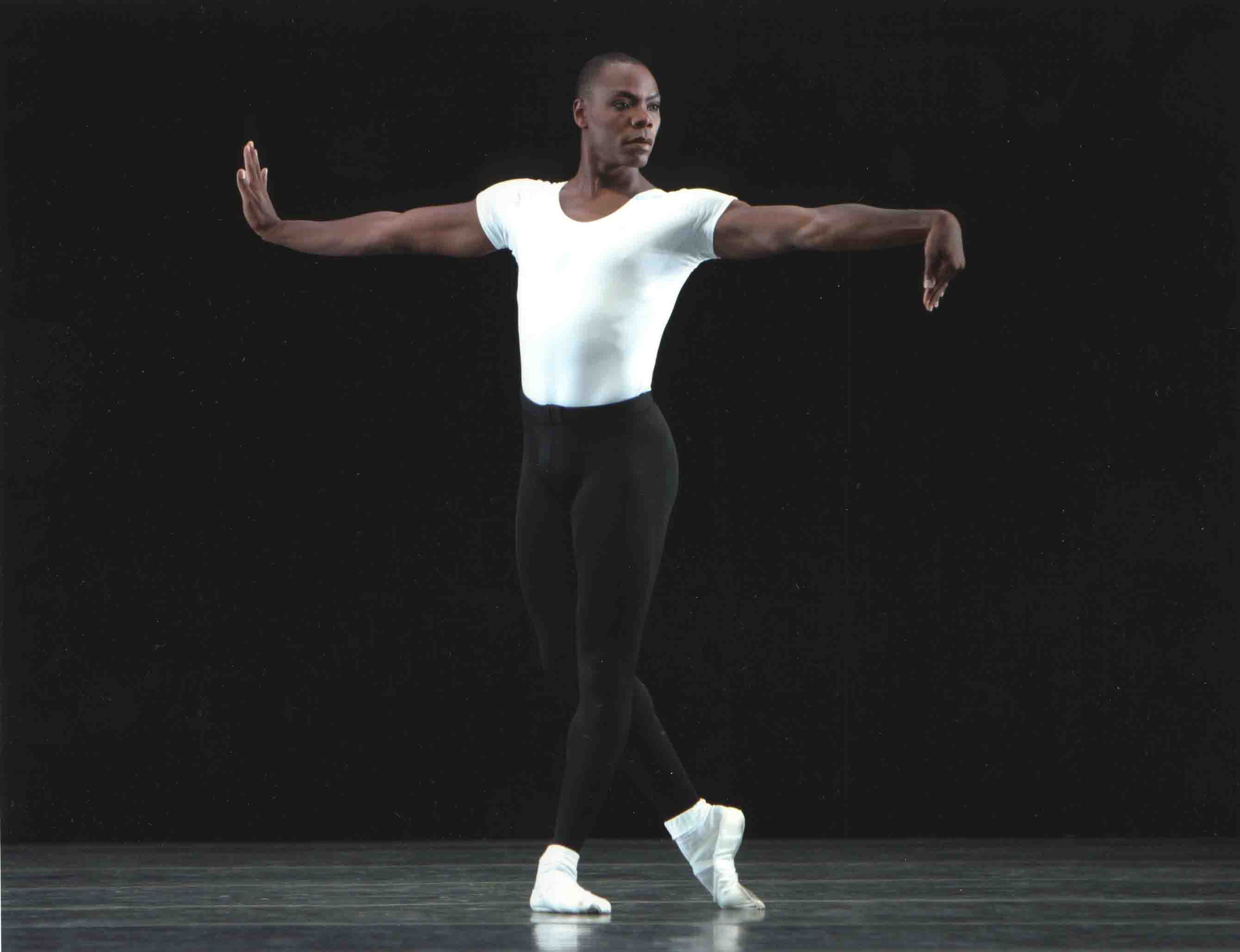

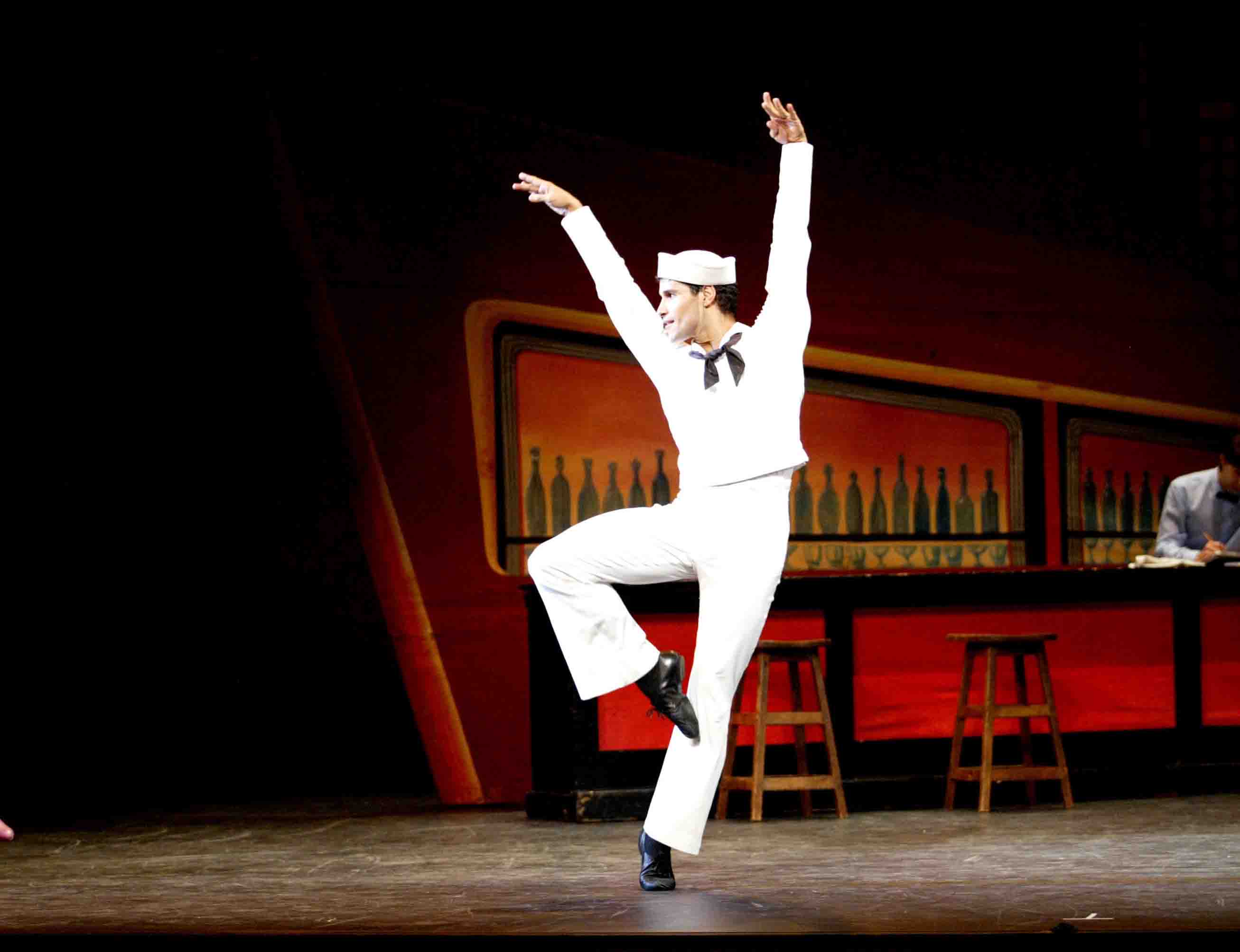

Jerome Robbins’s 1944 Fancy Free (perfectly matched with its vivid Leonard Bernstein score and its nifty Oliver Smith set) is pure Forties, yet it has remained a favorite to this day. Telling a tale of three sailors on shore leave, hopefully trolling for pick-ups, it maintains a mood typical of American optimism, all the while closely observing realities of individual temperament.

The sailors in the performance I saw were Craig Salstein (as the brash virtuoso, jumping from the corner saloon’s bar to land in a split), Marcelo Gomes (as the guy who does a sexy rhumba partnering an imaginary chair), and David Hallberg (as the wistful fellow, who gets the duet with the loveliest girl). Gomes and Hallberg seemed to be having the time of their lives, freed from the restraints of playing princes. The women were the duly lovely Julie Kent, whose smile can light up a 4,000-seat theater, and Kristi Boone, as the spirited, street-savvy gal with a red shoulder bag, who won’t take any nonsense. Karen Uphoff was a more than plausible choice for the impossibly pretty walk-on.

Then, on July 10, the final day of ABT’s season, there was Natalia Osipova, a phenomenon if not yet a great ballerina, as Juliet, in Kenneth MacMillan’s grand-scale version of star-crossed teenage love.

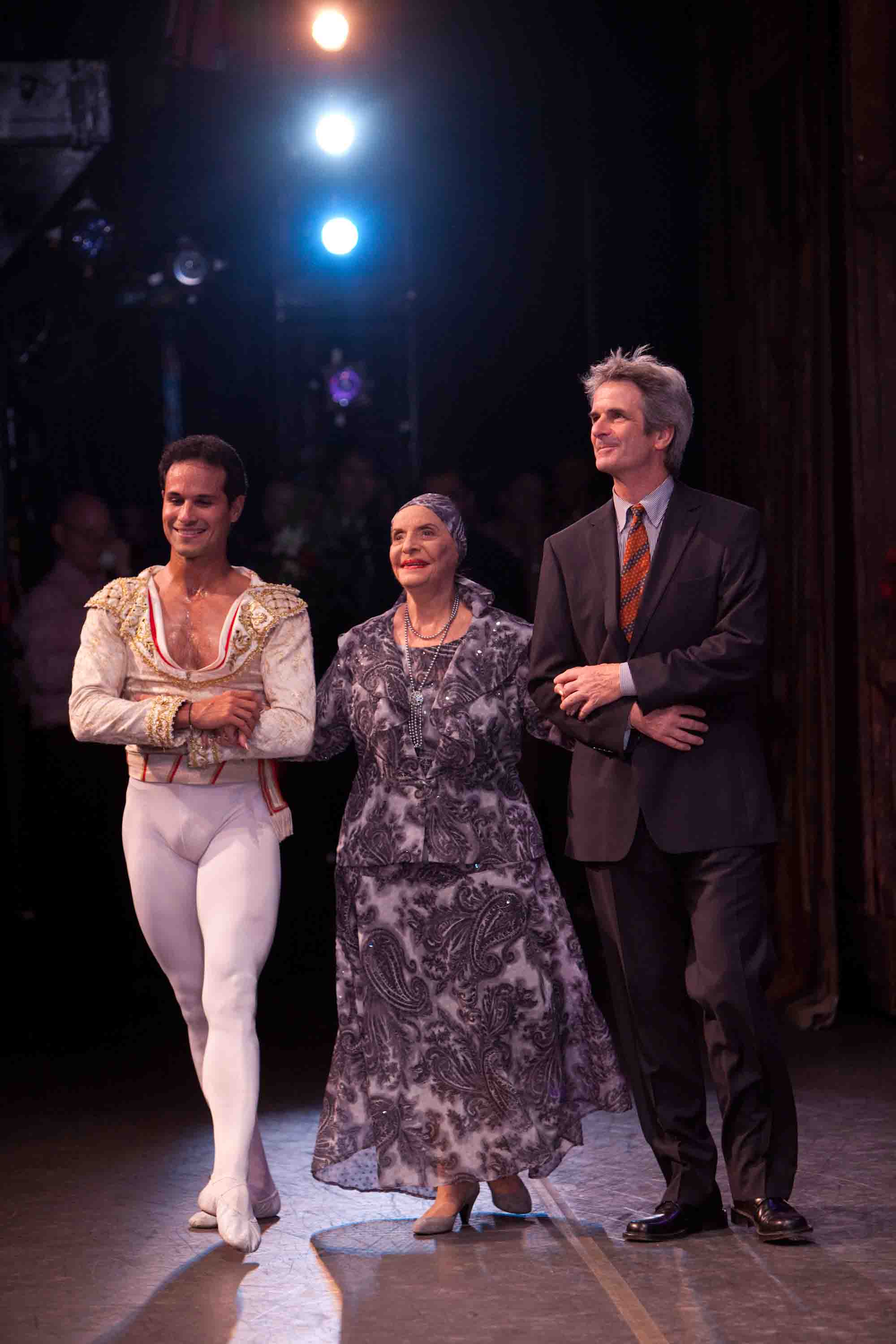

Fatal Attraction: Natalia Osipova as Juliet

Photo: Gene Schiavone

This was Osipova’s first Juliet ever. She had been resident with ABT for the entire season, learning the role in addition to giving a few spectacular performances in other ballets. The celebrated dramatic dancer Alessandra Ferri taught her the role and she was coached by Irina Kolpakova, the legendary Kirov ballerina, now an ABT ballet mistress, who understands that, in narrative dance, feeling and form must fuse.

Osipova’s interpretation of Juliet will grow with experience, but it’s already on the right track. The young star has proved her mettle by shaping Juliet’s story as a powerful arc that moves inexorably from the last moment of the girl’s childhood, rambunctiously playing with her nurse; through her developing awareness of love as it flowers by stages into unquenchable passion; to her suicide, which becomes the only possible response to her beloved’s.

Osipova also wisely suits her portrayal of Juliet to her own stage appearance and temperament. Abandoning the familiar aspect of Juliet that derives from Margot Fonteyn’s unforgettable portrayal–which makes the spectator feel that the terrible aspects of the tale should not be happening to so lovely a creature–Osipova judiciously abandons any attempt at “being beautiful.” She opts for realism.

This Juliet begins as a hyper-spirited youngster. Slowly, she’s tamed a little by experiencing routine gestures of admiration from Paris, the suitable suitor her parents have chosen for her, and her own shy, then slightly tender response, when she realizes it’s pleasant to be pleasing. This softening is immediately succeeded by her love-at-first-sight for Romeo–an enemy of her household. Once this sudden attraction (and his to her) becomes the sole focus of her being, she embraces its ecstatic fulfillment, which inevitably hurtles her toward death.

Stage by stage, Osipova spells out this evolution from child to adolescent to full-grown woman who makes her own choices and embraces the choices that are dictated by her heart. (Which is just as well, since her father and Paris finally try to bend her to their will with brute force.) Osipova presents Juliet’s trajectory in clear detail, even when events render her grotesque with horror and pain. Every gesture has a reason behind it. She does not–cannot, perhaps–weave a romantic spell, but her interpretation suits her in its boldness and reach. With time and luck, it could make her Juliet a genuinely tragic figure.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias