Matthew Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty: A Gothic Romance / New York City Center / October 23 – November 3, 2013

Matthew Bourne, who has changed classical ballet into sheer—often outrageous, often delicious—entertainment, has just brought to New York the last of his three works based on the glowing inheritance from the nineteenth century. Having tackled Swan Lake, with its deeply touching corps of male swans, and a Nutcracker that has changed many an audience dad from a guy reluctantly doing his duty toward his kids into an engaged spectator, he has just given Gotham Matthew Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty: A Gothic Romance. In all three pieces Bourne has been abetted by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whose music—infinitely resourceful and emotionally telling—is impossible to resist.

Hannah Vassallo as Aurora

Hannah Vassallo as Aurora

Photo: Simon Annand

Bourne’s Beauty shapes the original ballet to his own fantasy, which is weird, yes, and at the same time poignant. He even, for one thing, sculpts time in its flight. The first section of his version is set in the Victorian era; Aurora, the heroine of the work, is born in 1890, the year in which the original Beauty was created by Marius Petipa. She duly comes of age and falls victim to the curse of a hundred-year sleep in 1911. (Such details are communicated on a drop cloth, evidence of Bourne’s deep trust in—indeed, love for—the simplest of theatrical maneuvers.) Most interesting, perhaps, is that the final scene is set in the here and now, reminding viewers that self-realization, magic, and delight—in other words, the ingredients for happiness–can be theirs, though their acquisition does take some formidable personal effort.

Tom Jackson Greaves as Tantrum

Tom Jackson Greaves as Tantrum

Photo: Simon Annand

Bourne makes much of Aurora’s feisty personality in his Beauty—having the infant princess, played by a puppet, claw her way up a curtain and generally behave with the daring and spunk of the very young. This aspect of Aurora is carried through her youth with a spontaneous grace, with which she becomes the epitome of the modern woman, who knows what she wants. She wants, as her mate, a mere gamekeeper (shades of Lady Chatterley!) and she promptly sets out to get it, bravely defending herself from all obstacles including an evil suitor—a descendant of the wicked witch Carabosse, who carries out the curse in full vampire mode. At no point in her existence does Aurora behave like a ballerina. Bourne simply makes her a lovely, brave human creature—the kind of ideal any parent or partner would want as his or her own, with no desire to restrict her liberty.

Dominic North as Leo and Hannah Vassallo as Aurora

Dominic North as Leo and Hannah Vassallo as Aurora

Photo: Simon Annand

One of the most important and memorable things about this production is its design. The décor and costumes, both by Lez Brotherston, are not merely lavish and impressive, but utterly singular as well. Tutus (often worn by men) look as if they’ve been made of ribbons in many colors left free to ripple or fly as if gentle winds animated them. These visuals, in themselves icons of freedom, struck me as being the wish-fulfillment of a child endowed with the imagination of genius.

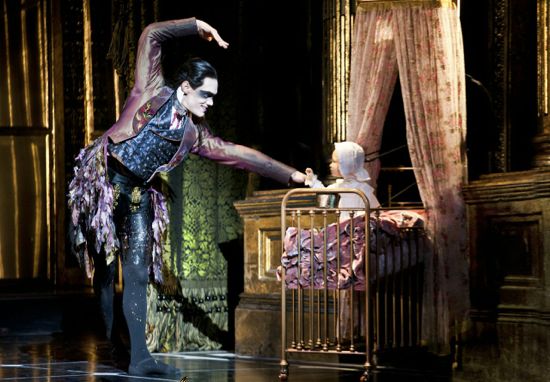

Tom Jackson Greaves as Caradoc and Hannah Vassallo as Aurora

Tom Jackson Greaves as Caradoc and Hannah Vassallo as Aurora

Photo: Simon Annand

The five fairies bring gifts to the newborn child, promising her Passion, Rebirth, Plenty, Spirit, and Temperament. (Contemporary productions select the virtues bestowed on Aurora variously.) The wicked witch Carabosse, a spoilsport if ever there was one, then casts her vicious spell: death by a pointed instrument, as in the original Beauty. I wonder if Petipa was aware of the sexual implication here. Perhaps only subconsciously. However the benevolent Lilac Fairy, a role Bourne interestingly assigns to a man (who’s called Count Lilac), is able to mitigate the horror, changing Aurora’s fate to a hundred-year sleep. Bourne doesn’t bother with the fact that Carabosse’s ill will stems from her accidentally being omitted from the guest list for the christening. I suppose Bourne didn’t want to give an entire scene to a social faux pas.

Bourne’s Beauty is wonderfully enhanced by puppetry, though the house program fails to give it a credit—a flaw that seems to me as grave as carelessly leaving Carabosse off the guest list. The aptness and detail of the puppet work reminded me of Basil Twist’s creations.

Mari Kamata

Mari Kamata

Photo: Simon Annand

You might call this ballet a takeoff, but I’m convinced you’d be mistaken. I think Bourne reveres the original—and is not greedily envious of its place “in the canon.” Can we not assume he is simply fashioning a clever and beautiful response to it, along with some useful and/or witty “corrections”?

Christopher Marney as Count Lilac

Christopher Marney as Count Lilac

Photo: Simon Annand

Truth to tell, Bourne is not a great choreographer. Alexei Ratmansky need have no fear of being bested in classical ballet’s challenge of making the body’s movement speak with an eloquence beyond words. Bourne’s ballets depend on a fairly literal depiction of admittedly curiouser and curiouser events that offer a compelling lesson, if we’re open to it. I can’t help thinking that a screening of it should be part of the “orientation” colleges provide for their first-year students, before the 17- and 18-year olds foolishly relinquish their naiveté.

Liam Mower as Count Lilac and Dominic North as Leo

Liam Mower as Count Lilac and Dominic North as Leo

Photo: Mikah Smillie

The piece requires sustained high energy from its dancers, so the production is mercifully double cast. The performance I saw featured Ashley Shaw as Aurora; Liam Mower as Count Lilac, King of the Fairies; Dominic North as Leo, the Royal Gamekeeper, whom Aurora fancies; and Tom Jackson Greaves as Carabosse (and, later Caradoc, her son). The house program might do well to contain a genealogy. Fetchingly designed, it could work as a souvenir.

© 2013 Tobi Tobias

Generous appreciation of a show I’d really love to see. Thank you for this report, Tobi.

Dear Tobi,

As always, a beautifully written review.

Because of your review I will go to see the show.

“…self-realization, magic, and delight–in other words the ingredients for happiness–” I might substitute self-fulfillment for self-realization, but that about sums up what I believe, and alas, the culture we live in does not. None of those ingredients for happiness necessarily requires money, although it certainly helps. Seems to me that while Mr. Bourne may not be a great choreographer, he is a great showman, and is therefore in the tradition of Petipa, Bournonville and Balanchine. I deduce this from TT’s impeccable description of his “Sleeping Beauty” and profoundly wish I could see it with mine own eyes.

Reading your BEAUTY piece with the backdrop of Ponte Vecchio is

surreal.

Tobi, this review has some of the magic and delight you attribute to the dance itself. A pleasure to read, and it made me want to see it. Onward!

Unfortunately we missed the Bourne Sleeping Beauty, which sounds interesting if rather confused, with adding the all-too-fashionable vampires to cover the time lapses. Is it noteworthy that Christopher Wheeldon’s slightly earlier Alice in Wonderland for the Royal Ballet added a gardener’s boy who comes to partner Alice in her dream, just as Bourne adds a young gamekeeper?

But I would point out that this is Bourne’s fourth work remaking a nineteenth century ballet. In addition to the three Tchaikovsky scores, in 1994, the year before Swan Lake, he made his version of La Sylphide, using the Løvenskiold score plus some additions, as Highland Fling. And in 1997 came his Cinderella with the Prokofiev score. Neither has been seen in this country, I believe.

I’m a big Matthew Bourne fan too bad i missed this event, if I had known at the time i would have bben first row for sure.