Wendy Whelan knows how to make her “sunset years,” so to speak, work well as a much-admired principal dancer—a veteran of over a quarter-century with the New York City Ballet. With this company, astute technique has become an essential—indeed the foremost—of a star dancer’s attributes, competing only with musicality, which is not Whelan’s primary forte. And, at the age of 47, some of this ballerina’s technical prowess, which was distinctive as she displayed it, is naturally failing her. Anatomy is remorseless.

Of late, presumably conforming to the company’s wishes, Whelan performs fewer roles. One of the ploys that sustains her reputation, showing off the kind of movement in which she is now most poignant, is to dance slowly, with precise delicacy. She takes on roles in which legato becomes almost a fetish. A beautiful fetish, I would add, though I wouldn’t want to watch a daily dose of it unless I was also getting to see its opposite—to say nothing of its middle ground—in the course of a program.

It would seem that a goodly number of the School of American Ballet nymphets, from whom Whelan’s successor will eventually emerge, admire, even revere her. For many, she is their role model. See, for example, her account of the duet in Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain—it’s become almost an iconic piece for her. Its subject, incidentally, is a quiet but heart-wrenching farewell. Jock Soto, who originated the role of the man in the duet, was about to retire from the company, a great loss to all concerned.

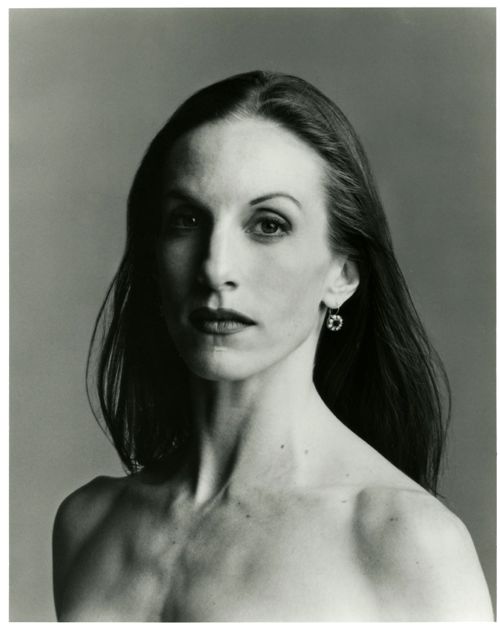

Tall, rail thin (her body sometimes looks alarmingly undernourished in roles not requiring tights, which smooth out many a revelation), with the profile of a crown princess, Whelan manages to appear imposing and vulnerable at the same time. The critic John Rockwell has aptly referred to her “sinewy lightness.” Her arms often fall into a hieratic angularity—as if insisting on an important part of her birthright. Typically, every move she makes, she makes her own as well as the choreographer’s.

Most interesting as a career move in Whelan’s current life is her expanding the way she can still be seen as a dancer who looks very special. Characteristic of the arrangements she has worked out is her upcoming show, Restless Creature, which will have its official premiere at Jacob’s Pillow’s Ted Shawn Theater, August 14-18. For this she has commissioned four ballets by four newish choreographers—works presumably tailored to the assets she still has available, which, so far, are many. The choreographers invited to merge their imaginations with hers are Kyle Abraham, Josh Beamish, Brian Brooks, and Alejandro Cerrudo.

In some ways I wish she wouldn’t pursue this activity. In the end, it’s always a sad and losing battle. For other reasons, I hope she will. If ever there were a dancer out to make the most of herself—and expend enormous valor of body and soul in doing so, it is Whelan. May I confess that I would prefer a gentler goodbye? Something like Kyra Nichols’s last few seasons, which made “less is more” piercingly meaningful? No, probably not. The two dancers harbored very disparate souls. At any event the choice is hardly up to me.

Note: On April 14 and 15 at 7:30, the Works & Process series at the Guggenheim Museum was devoted to Whelan and her Restless Creature. Ella Baff moderated a discussion with Whelan and the quartet of choreographers she had commissioned for the piece.

Photo: David Michalek

© 2013 Tobi Tobias

As usual Tobi, you are eloquent and sensitive in your writing. A great dancer in the twilight of his or her career has limited choices. Do they give it all up and walk away, or find new paths that enable them to work with the reality of their physical capabilities? I personally prefer the second option and I look forward to seeing Wendy in this next phase. As long as she feels motivated, that is good enough for me!

Tobi, thanks for addressing this interesting turn in Whelan’s career. What is missing, for me, in your essay (and the general discourse about Whelan at this moment) is the implication of her choice to work with contemporary dance choreographers in the twilight of her performance career in ballet. It seems as if she (and you) are implying that, without all of her classical technique at hand, that the “modern dance” is her next best choice. This suggests that modern dance is for slumming. This is obnoxious. Whelan spent most of her life achieving heights of classical balletic accomplishments. Others chose to devote themselves to another set of aesthetics. Whelan seems to think that she can achieve performance in the contemporary dance genre as a less-than proposition. While recent essays in the New York Times have spoken of her fantastic work ethic (and I’m sure she is very committed), work ethic is not enough. Time for any body to absorb a variety of new and differently embodied aesthetics is necessary; it is important to note that the choreographers she has chosen are exemplary in their complex and subtle contemporary aesthetics. Does she have the time? Well, August is here and the Pillow awaits. I’m doubtful.

While I agree that After the Rain was a marvelous vehicle for both Whelan and Soto, I can only applaud Whelan’s eagerness to look forward to different kinds of projects such as her weekend at Jacob’s Pillow. I will not be there this summer but I will certainly follow her path in the coming year. I marveled at the way she performed in the Ratmansky works for NYCB and others. Her dancing has become increasingly expressive at a range of speeds and contexts.

The program has taken place, and kudos go to the choreographers for being so attentive to what Whelan is and needs. She can now make curves (perhaps marriage gave her softness), but her pigeon-breasted, skeletal frame still gives me anguish. And no: she hasn’t achieved the weightedness of modern dance. After all, Soto brought the best out of her.

“Anatomy is remorseless.” Ain’t it the truth, and not just for dancers. I’m interested that no one has commented on Baryshnikov’s explorations of modern and contemporary movement after he cast off his princely tights and tunic; I especially liked the show he did with Anna Laguna, wasn’t as impressed with what he did with Mark Morris years ago.

Hi Martha,

Good point about Baryshnikov. The thought I had in mind while typing earlier about Whelan was that my experience with Baryshnikov in some of his post-modern forays was that standing still without emanating a princely aura seemed very difficult for him. The standing still part is okay, but the aura part was very hard for him to reduce. How it is that one learns this in a post-modern embodiment is difficult to say, but seeing it NOT done is very clear in my memory.

Laura Peterson replies to Jeff Friedman: Thank you.