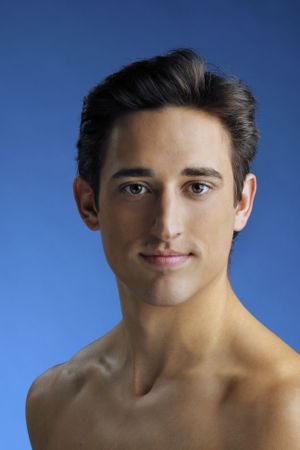

New York City Ballet: Justin Peck’s new work, Paz de la Jolla / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 31, February 2, 6, and 8, 2013

Justin Peck, choreographer of Paz de la Jolla for New York City Ballet

Justin Peck, choreographer of Paz de la Jolla for New York City Ballet

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Justin Peck, a 25-year-old member of New York City Ballet’s corps de ballet, seems to have lots of useful ideas and moods in his unstoppably busy brain. His latest work for the company is Paz de la Jolla (the peacefulness of La Jolla) and set to a similarly evocative score along the same lines by Bohuslav Martinů.

The choreography is typical of Peck’s prescience about the useful “rules” of choreography—and those that are not. He is so informed that you feel he’s equipped to make a reasonably commendable ballet in his sleep and that if the results didn’t satisfy him, he could tweak his material until they did.

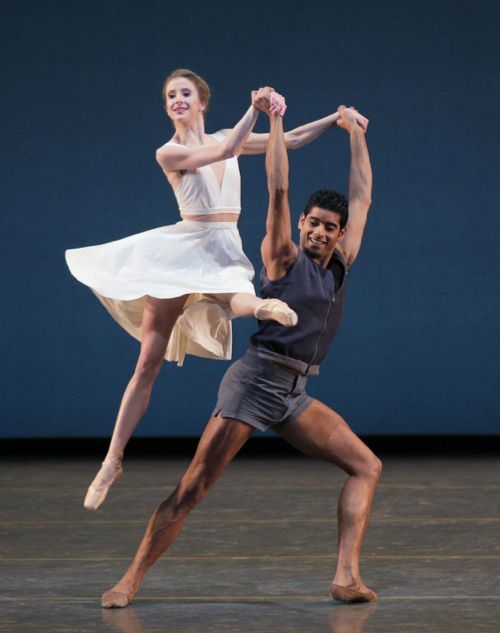

Beach Boys in Peck’s Paz de la Jolla

Beach Boys in Peck’s Paz de la Jolla

Photo: Paul Kolnik

For Paz de la Jolla Peck wisely follows the trite but still instructive admonition to writers at the starting gate of their careers: “Write what you know.” In a good many ways, Paz de la Jolla epitomizes the sensuous pleasure native to southern California culture, in which he grew up. From his description, it was a wonder he ever left—but he wanted to dance and he believed that that would happen most effectively in New York, which, for him, it did.

Sterling Hyltin and Amar Ramasar, as the lovers in Paz de la Jolla

Sterling Hyltin and Amar Ramasar, as the lovers in Paz de la Jolla

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The warmth of the Californian climate (Peck often lets you see it in the way the dancers move) matched by Martinů’s evocative music arouse the happily susceptible body and soul. Peck sets off the benign effect by slight additions from the underside of joy, and the effect was accidentally enlarged by the first several performances’ taking place in New York during a period of freezing snow, icy streets to navigate, and bouts of high winds that are all too prevalent in our local winter weather. Getting to the theater without incident was an adventure in itself.

Perhaps Peck’s development as a choreographer will one day follow the writer Grace Paley’s instruction: “Write about what you don’t know about what you know.”

The ballet opens with lots of swift brilliant movement, laced with authentic-looking split-second choices about what happens next.

Hyperactive arms and legs, like the long, thin limbs of gangly teenagers, shoot this way and that. It’s clear from the get-go that Tiler Peck (no relation to the choreographer) is the tomboy in the bunch; Sterling Hyltin, the sweetheart; Amar Ramasar, the eternal boyfriend. The ground is the sandy beach; the 15-member corps de ballet, costumed in blue, is the ocean—as dangerous as it is beautiful. The subsequent goings on are melodramatic in a predictable seaside vein, as if Peck were saying “Well, it’s always like this, isn’t it?”.

There’s a lovely—and refreshingly original—moment during the obligatory lovers’ pas de deux when Ramasar moves away from Hyltin for a moment, as if captivated by his own dream, but then returns—as most reliable tales, other than Hans Christian Andersen’s, would insist—to focus on her.

Now and then the water figures have an ominous air. They dally with Hyltin while her boyfriend dozes, then lure her into their midst; when they vanish, she lies on the shore alone, as if dead. The problem here, as well as with the ballet as a whole, is that, with everything happening at top speed, you’re not always sure what’s going on. The choreographer insists upon a happy ending, though; you can’t blame him, he’s still young and Martinů has given him no “death music.”

Hyltin, Ramasar, and Tiler Peck, as the principals in Paz de la Jolla

Hyltin, Ramasar, and Tiler Peck, as the principals in Paz de la Jolla

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The casting for La Jolla is happily conventional: Hyltin is the young woman whose evident, indeed sole, job in life is to be beloved. She calmly accepts her duties without conflict or protest; they are her fate. Tiler Peck is surefooted and delightful as an emissary of exuberance and delight, while Amar Ramasar is, as almost always, the guy immediately recognizable as “the prince.” At first glance you might think the three were sent over from Central Casting, but they’re far better—the very models of their respective roles.

Peck, as the woman who needs no support, in Paz de la Jolla

Peck, as the woman who needs no support, in Paz de la Jolla

Photo: Paul Kolnik

All 18 in the cast look terrific in the beach clothes designed for them by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung, as well they might, since their training makes them so eye-worthy.

As its its right, the ballet is confined to the halcyon side of life in La Jolla, indirectly to its climate and to its lovely long meandering shoreline. For such reasons the place has, in real life, become a paradise for the greatly privileged. (Wikipedia tells us that Mitt Romney has a vacation house there.) Let that pass, but not this: anti-Semitism had a long reign in La Jolla. Still the ballet itself is strong and consistent enough to ignore the darker aspects of the location’s history—from the truly offensive to just plain human failings. Nevertheless, what Peck might most usefully direct his attention to next, is to find ways in which to make his dancers look like real (though imaginary) people. For examples of this he might pay acute attention to Alexei Ratmansky, who delights in the human race.

© 2013 Tobi Tobias

Haven’t seen the ballet yet, but I love the Grace Paley quotation. Thanks!

Thank you!

Going to see this on Friday, February 8th. Can’t wait.

Justin Peck is on his way to becoming a major choreographer. It’s fun to see him take his choreographic bows, and then go on to appear as a corps dancer in Concerto DSCH. Do you see a Ratmansky influence in his work, as I believe I do?

Dear Dr. Steeg,

Thank you for writing. As my review indicates, I can’t say I do see a resemblance between Peck and Ratmansky, but Peck is still young and has time to absorb many useful influences. Like you, I enjoy the idea of his still being active as a dancer as well as having a good beginning as a choreographer.

Can you explain the relationship between the Spanish title and the Czech composer? I’m curious.

You’ll have to read one of those brief lives of the composer. The NYCB’s music notes had some info. For more, you might try Grove’s or simply ask a librarian in the Music Department at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts to point you in the right direction.

Martinů did the bulk of his composing in the States between 1941 and 1953 and no doubt visited Southern California.

I breezed along in your review of the new Justin Peck ballet, until near the end, when you introduced a matter of social reality: the anti-Semitic history of Justin Peck’s idealized La Jolla. I was startled to find it in a ballet review?) and admired you. But I wanted to know more.

Your moral interjection led me to a scholarly piece in a 1996 issue of American Jewish History (Mary Ellen Stratthaus, “Flaw in the Jewel”), providing an account of discriminatory policies in real estate plus other aspects of social and economic life in La Jolla through the 1950’s.

Amar Ramasar would have been unwelcome in La Jolla, even on the beach, as recently as a few generations ago. Jews (considered a “race” in sunny California) and also Mexicans, blacks, Latinos, Asians, Hawaiians, Filipinos, all-“non-Caucasians” were kept out.

The barriers went down only when the University of California sought to establish a campus in the La Jolla area. “How can there be a university without Jews on the faculty?” was the argument of a (Scripps-Howard related) reformer, pointing to the fact that professors would need housing. Eventually the “people of discrimination” [realtor sales talk] caved, but not without legal battles.

Maybe you already know all this, and more. Do you know La Jolla?

Many thanks for bringing a moral issue to the beautiful beach.