Paris Opera Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 11-22, 2012

The Paris Opera Ballet, playing at the David H. Koch through July 22, gets the prize for vintage achievement. Formed in 1669, it has the distinction of being the world’s oldest classical ballet troupe. The academy that produces most of its dancers dates from 1713. Naturally, this legendary institution, absent from New York for 16 years, had to re-introduce itself.

The Paris Opera Ballet’s Aurélie Dupont (center, held aloft) with fellow artists of the company in Serge Lifar’s Suite en Blanc

The Paris Opera Ballet’s Aurélie Dupont (center, held aloft) with fellow artists of the company in Serge Lifar’s Suite en Blanc

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The first of the three ballets it performed on its opening night in New York declared that exquisite technique rules the company’s aesthetic. Serge Lifar’s Suite en Blanc, set to Édouard Lalo’s score for Namouna, is essentially a compendium of steps, steps immaculately executed by the dancers—almost all trained at the company’s school from early childhood—so that they seem to be the definitive, textbook, version of that step. The goal is, quite simply, perfection. Onlookers will find this sublime, curious, or off-putting, according to their taste. As for its being a ballet about ballet, it’s a distant cousin of Harald Lander’s Études, often performed by American Ballet Theatre, but neither gaudy nor wild. Suite en Blanc is completely confined within the parameters of good taste.

Some, almost random, particulars:

The women’s feet—in their spanking clean, neatly tied pink satin pointe shoes—seem to caress the stage floor and, incredibly, make no sound on the landings from jumps and leaps or on gentle pitter-pattering runs.

The women’s arms are graceful and ornamental, tracing filigreed patterns on the air. The head, neck, and shoulders harmonize scrupulously to produce an effect called épaulement, something Balanchine ignored, because it interfered with the speed he wanted and, perhaps, because it looked old-fashioned.

There are women who can balance forever on one foot—en pointe, of course—turning themselves into an unwavering middle-weight piece of sculpture, apparently through sheer will or perhaps a code of honor.

Everyone in the company, it seems, can turn like mad, some even like gyroscopes. Among the men the finishes—always the telling part of a turn—are sometimes uneven.

The men bend their knees slightly and shoot their bodies directly up into the air, beating their feet together, clearly and firmly, then landing neatly. Missteps, even on a first performance in an unfamiliar theater, are few and clearly destined for eradication.

The men are not only adept partners, but also infinitely polite and respectful cavaliers as well. And they manage to pull off impressive athletic feats without looking like cavemen. True this unremitting chivalry and control may exasperate the New York spectator. We’re simply not used to it.

Throughout, there’s not much variation in the weight of a step. Even in the air, the dancers don’t create the illusion of being ethereal—or, on the ground, impressively forceful. What they’re aiming for, I guess, is sublimity.

Aurélie Dupont and Benjamin Pech in Suite en Blanc

Aurélie Dupont and Benjamin Pech in Suite en Blanc

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The high point of Suite en Blanc is a duet in which I saw Aurélie Dupont, a ravishing dancer nearing the company’s compulsory retirement age of 42, sveltely partnered one evening by Benjamin Pech and the next by Mathieu Ganio. Dupont is undeniably a beauty—in both face and figure, a superb dancer with the lush quality of a Suzanne Farrell or a Sara Mearns, and a role model of calm, confident serenity. She exemplifies the rank of étoile (star)—which the company awards to those artists who have a luminous quality that draws viewers’ attention like a magnet and makes them rejoice in what they see. There’s a marvelous moment in the duet where the man walks forward holding her body above the floor and she “walks” too—on air. And another in which she lifts her arms over her head and intertwines her fingers as if to indicate at once the crown of a regent and the halo of an angel. If I had known about her earlier, I would have traveled to Paris more often.

Isabelle Ciaravola and Jérémie Bélingard in Roland Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Isabelle Ciaravola and Jérémie Bélingard in Roland Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Photo: Stephanie Berger

It took me a second viewing to figure out the tale Roland Petit’s 1974 L’Arlésienne was trying to tell and even then the story felt wrong-headed. The title itself, The Woman from Arles, appropriated from the Bizet score to which it’s set, is a red herring because the central figure of the ballet is a young man. He and the woman his fellow villagers—a 16-member corps—assume he will marry and settle down with, can’t make their relationship work because the youth has visions—visions of a love that’s utterly beyond earthly reach. Think of La Sylphide, in which James, slated to marry the charming, down-to-earth Effie, feels trapped in the ordinariness of his bride-to-be and the domestic life their community expects them to lead together, and so dreams of a love that’s literally unearthly. You know how that one ends.

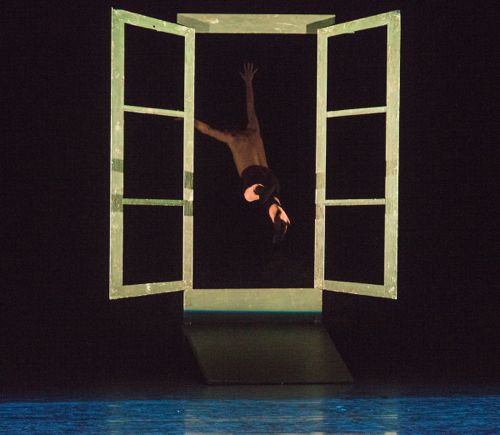

The woman, played paper-doll style (is this how Our Hero thinks of her?) by Isabelle Ciaravola and more humanly and sweetly by Nolwenn Daniel, approaches her intended again and again—this is a tediously long ballet—and the two do try to connect, to no avail. He grows more and more possessed by his visions and allergic to her overtures and at last jumps out of a suddenly and conveniently appearing window to his death.

Jérémie Bélingard in Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Jérémie Bélingard in Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The dancers I preferred in the leading roles were Jérémie Bélingard in the opening night cast—his acting was so convincing I almost believed in the goings on–and Nolwenn Daniel (who played a sweetheart any man would be proud to win) in the second performance.

Bolero: You know that Ravel music. And it’s still just as long as you remember. It belabors a simple melody, assuming that repetition, hand in hand with escalating volume and augmenting instrumentation, will hypnotize the hearer. The composer, it’s said, told a friend that he found the little phrase itself “insistent.” Apparently Bronislava Nijinska thought so too and was the first to choreograph the score, in 1928.

Nicolas Le Riche in the central role of Maurice Béjart’s Bolero

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The Paris Opera Ballet does Maurice Béjart’s 1961 version. It’s an audience pleaser, god knows; I find it unbearable. The choreography features a man or a woman (I saw Nicolas Le Riche on opening night, Marie-Agnès Gillot the following evening), discreetly wearing as little as possible under the circumstances, standing on a red oval table to pulsate, gyrate, and gesticulate nonstop with increasing fervor. He (or she) is bordered on all three sides of the stage by a row of dancers who become drawn into the rite until, at the finish, they close in and lunge at the figure on the table, suggesting a synchronized orgasm.

Nicolas Le Riche and the male ensemble in Bolero

Nicolas Le Riche and the male ensemble in Bolero

Photo: Stephanie Berger

My guest for the opening night program, with which Bolero concluded—with a bang, you might say–condemned the piece, which she was seeing for the first time, as incredibly vulgar. I was bored by the trite choreography, but deeply impressed by the sensuous power and selfless dedication to the enterprise of the two dancers I saw in the leading role. It was definitely a case in which maturity counted. The audience as a whole went crazy for it. Standing ovation and all that. Yelps of delight.

The POB’s mixed repertory program will be followed by Giselle, created for the company in 1841. I can’t wait.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias

Love your wit !

Has the ensemble in the Béjart “Boléro” ever been coed? I seem to recall that in the beginning when there was a woman on the table, the crowd was all male and vice versa. Then came the scandale of an all-male cast, top to bottom (you should excuse the expression), led by the phocine Jorge Dunn, sauna attendant in excelsis. (Didn’t Nureyev do the number that way, too?) An all-female cast would seem an impossibility, given the music, not that such considerations would have been likely to sway Béjart. I wonder what options are open today, and which ones have the choreographer’s imprimatur. I wonder also that I should wonder, loathing the ballet as I do. But the score is not what we often think it is. Leading the New York Philharmonic a few seasons ago, Riccardo Muti proposed a stern, transcendental reading: deeply Spanish, even Inquisitorial. Wish you’d heard it.

At last I saw the same program you write about, at least the July 11th performance. I appreciate what you wrote about “Suite en Blanc.” The dancers were impeccable and I wasn’t familiar with any of the cast so I would have to say they were all memorable as a cast. The stage design was also memorable with its use of levels and symmetry. Even during the dancing I started to wonder about the emphasis on pure form at the sacrifice of expression of feeling. Was it something about Serge Lifar as a choreographer perhaps? I had heard he ran the Paris Opera with tight control, but didn’t many who came after him? Anyhow it was a great opener and introduced the company well.

“L’Arlessiene” started to remind me of “Les Noces” but then not. It seemed too long, for one thing. And the role of Frederi with Jeremie Belingard was wonderfully danced. He clearly didn’t want the relationship with Vivette. In today’s world he wouldn’t have jumped out the window but at that point I thought of “Spectre de la Rose” and I started to lose sympathy for him.

As for “Bolero”, the performance by Nicholas Le Riche was great enough to outweigh the memories of all the others I’d seen in the role. I think that was mainly why the audience went crazy at the end.

I’m sorry I won’t be there for “Giselle.”

Tobi, What I first realized when I read this spectacular piece of writing was how very much you see–and how much I miss. What an eye for the particulars; well, I guess that’s your job but you certainly do it with eclat. And thank you for clarifying what “L’Arlesienne” was about. It did seem to me that she was chasing him around! To no avail, apparently. As far as the Bejart–a bit of a thrill to see myself cited. Thanks for all of this, done with your usual grace and acuity.

Thanks for the accurate review.

I echo Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s enconium to TT’s writing and acuity of observation; not only does she see what many others, including her colleagues, sometimes do not, she remembers what she saw when she sits down to write.

I have a question however about her statement re Balanchine and epaulement, since someone I was interviewing about Todd Bolender–I think it was Jonnie Greene– told me that he, who originated Phlegmatic in “4T’s” and the Sarabande in “Agon,” had the most beautiful epaulement she’d ever seen.

I have a secret affection for “Bolero,” the score, particularly when I remember that it is meant to be “industrial” music. I thought Nicolo Fonte used it very well, and in this industrial context, for a ballet commissioned by Oregon Ballet Theatre in 2008. It is now in the repertoires of the Washington Ballet and Ballet West.

I must say that I hadn’t particularly wanted to see the POB on this tour, but having read TT’s review of its first program, I regret that I won’t be able to. Looking forward therefore to having her put me into the theater with her for “Giselle” and Bausch’s version of “Orpheus.”

What a perceptive, persuasive (you draw me in and along) and above all generous review. Thank you! I too wish I had been to Paris to see Aurélie Dupont more often.

Yelping with delight!

So glad you feel the same as I about “Bolero,” Tobi. Crowd pleaser or not, surely the Paris Opera Ballet has so many pieces to choose from that they might have brought.

I do agree with one of your readers [Alice Halpern –Ed.] in regard to “Les Noces.” Just for a moment though.

Unfortunately I do not have a ticket for “Giselle.” I am really sad.

However, I can’t wait until I see the Bausch.

I’m really looking forward to your next posting.

The review makes up for what I missed, since I was too late to get tickets. However, reading your description of the Lifar ballet reminded me that this was a ballet created to please the Nazis. While Lifar managed to stay in power even under the Occupation and afterwards, there have always been whispers that he was more pro-Nazi than the French care to admit. So perhaps the formality of the ballet and its lack of expressiveness and feeling was a way to satisfy the German attitudes about a French art?

it is true that the Paris dancers are truly beautiful, although I must admit that when I lived in Paris I saw them do an evening of Balanchine and immediately got homesick for the New York City Ballet. Their interpretation of Balanchine is much closer to the 19th century traditions they know best than to the 20th century ballet Balanchine invented.

As always, Tobi, it is a pleasure to read what you have to say.

Wonderful, as usual.

I read your piece on the mixed-rep Paris Opera Balllet program on Sunday morning and went to the matinee in the afternoon. Every word and feeling you conveyed is exactly what I felt.

I first saw “Bolero” outdoors, in San Francisco in the 1970’s and couldn’t believe the tremendously positive audience reception to the trite, repetitive, boring “ballet.” I believe it was all men, and somehow I got the impression (it was the first time I’d seen Bejart) that Bejart hated women. Now why do you think that was? When Suzanne Farrell joined his company after that, I grieved for her sanity.

Why do people let “artists” get away with crap like that?

Just speaking my mind…….

Oops! Tobi, the second most important thing, in Balanchine’s class. after tendus, was epaulment. We worked on the head position with the tilt of the head in croise, efface and the profile head in ecarte forever in class. The one thing he always said was, he didn’t want to see FLAT DANCERS!!

P.S. Great review.