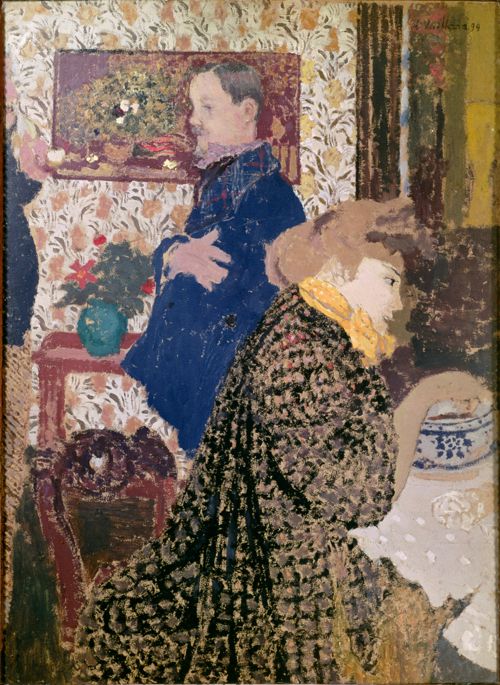

Edouard Vuillard, Misia and Vallotton at Villeneuve, 1899, oil on cardboard. Collection of William Kelly Simpson.

As you can see from the Jewish Museum’s rich retrospective of his pictures, Edouard Vuillard (1868 – 1940) was obsessed by fractured patterns. Clothing in figured fabric and décor vie for attention with the people represented. Dresses, wallpaper, exuberant plants refusing to confirm that they’re indoors or out, and secondary human figures appearing as half-visible ghosts charge the viewer’s retinae and create a haunting—even ominous—mood of instability. In the picture above, the man and woman ignore each other’s presence, while the man’s head becomes part of the painting behind him and the woman’s pet dog, begging for a treat, nearly disappears against the rambunctious checkerboard of her dress. Vuillard gets his showing at the Jewish Museum because he was befriended by powerful Jewish art enthusiasts in the Paris of his day. Could there be any connection, I wonder, between his hallucinatory view of the world and the mystical aspects of the Jewish faith?

Edouard Vuillard: A Painter and His Muses, 1890-1940 / The Jewish Museum, NYC / May 4 – September 23, 2012

© 2012 Tobi Tobias

An interesting question, TT, and I’d like to explore it a bit, having studied Martin Buber pretty extensively in college. Is the painting above an illustration for “I and Thou”? Do the complex patterns in the painting illustrate Hassidic concepts, which are complex and extremely well-designed? Beats the hell out of me, but I think it’s a very interesting painting and I’m pleased to see you writing again about art that in the literal sense stands still!

Vuillard is among my favorite artists. I travel to see shows of Vuillard paintings and prints, and I think about how he combines prints even when I dress. For years I used his paintings as a way to inspire my own dressing – prints with prints, way before it was fashionable. In fact, people used to comment that my prints didn’t “go” together, as if matching was ever the point. So it comes as no surprise that you, Tobi, are also a Vuillard fanatic, since I have noticed that when reading your blog I get a different perspective on the very things that interest me.

But the Jewish question you ask has raised my historical hackles. As an historian of 19th century France, I know something about these Jews and they were by choice and political sympathies totally assimilated, a long way from their religious Jewish roots. Moreover, in general they weren’t Eastern European to begin with, but Spanish Jews who fled Spain and settled in Bordeaux or Alsatian Jews, some of whom had been Eastern European Jews in the 15th and 16th centuries, but settled in France quite early and, by the time of Vuillard, chose France when Alsace became German after 1870. Vuillard’s Jewish circle was closer to those described by Edmund de Waal in his amazing book The Hare with the Amber Eyes, or Proust’s mother’s family. Of course they showed up in Synagogue now and then, but like the Dreyfus family, they were French above all else. We see Vuillard’s world as hallucinatory, but I am wondering if it isn’t something as simple as bad French taste (I remember when I first went to France how much I hated the decor it was so fussy) exaggerated and foreshortened to create an illusion of a rich tapestry. Indeed, Vuillard’s paintings reflect a quintessential French taste, but abstracted to move us forward into a modern sensibility. It reminds me of Gertrude Stein’s comment [in her book, Paris, France] that the reason the 20th century was created in France was because France itself was so traditional and the hats were forever beautiful and chic.

IN REPLY TO ANN ILAN ALTER:

Oh, I love Vuillard too! I came under his work’s spell at the Met’s wonderful 2001 exhibit “Beyond the Easel” and insisted on a vacation in Montreal just to see the major 2003 Vuillard retrospective at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Vuillard’s widowed mother ran a dressmaking business in the family’s Paris apartment. Perhaps growing up surrounded by heaps of fabric in close juxtaposition with elaborately patterned wallpaper, furniture, carpets, and the seamstresses’ own dresses gave Vuillard his eye for the unexpected harmony in a happy profusion. I’ve never found his work particularly hallucinatory, but its affective power is tremendous.

Vuillard drew on his mother’s workshop for images in a number of his works. “Interior with Worktable” (aka “The Suitor”) is one of my favorites. It is not in the Jewish Museum’s current exhibition, but you can see an image of it here: http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/edouard-vuillard/interior-of-the-work-table.

IN RESPONSE TO KATHLEEN O’CONNELL:

Thank you for your two Comments. I urge readers to view the reproduction of the Vuillard picture you mention–“The Suitor.” It provides so much about what you describe as Vuillard’s “affective power.”

RESPONSE TO MARTHA ULLLMAN WEST:

Ginger:

So were you and I in the same small classes with Harold Stahmer on Buber? Definitely among my more memorable experiences at Barnard!

Emily (Fowler) Omura

It might be equally interesting to expand on the painting’s subjects: Misia Sert (born Godebska) and Félix Vallotton, artist associated with the Nabis. What was going on at Villeneuve in this 1899 painting?