Mark Morris Dance Group / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / March 1-3, 2012

The only information I have to offer about the world premiere of Mark Morris’ A Choral Fantasy is descriptive. The relatively brief, high-spirited piece is set to Beethoven’s Fantasia in C Minor for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra, Op. 80.

Amber Star Merkens in Mark Morris’ A Choral Fantasy

Amber Star Merkens in Mark Morris’ A Choral Fantasy

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The dance opens with a single tall, lean figure taking the stage and, after a few bold, vigorous movements, flying off to leave the space empty, merely illuminated in a tint the color of the sea. This emptiness will be repeated throughout the piece, as if to remind viewers of the crucial role space itself plays in choreography.

The figure is Amber Star Merkens, who will lead the other 14 dancers in the cast. She and they are clothed alike (by Isaac Mizrahi) in a quasi-military uniform consisting of a sleeveless top and trousers, both a deep forest green. A large pale X is embossed on both chest and back of the outfit; a matching line ripples down the side of the trousers.

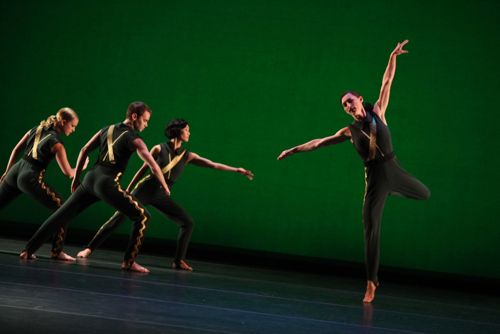

Merkens (far right) with members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in A Choral Fantasy

Merkens (far right) with members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in A Choral Fantasy

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Again and again Merkens summons her squad and directs its activities, often referring to the marching theme that dominates the music. At one stunning moment the motif is carried out by the full cast’s marching across the stage, once in each direction, with the firm footfalls that indicate unassailable confidence. In a dissenting tableau, which vanishes quickly after it appears, three dancers lie on the floor like fallen troops, while Merkens leans over them, troubled.

In every segment Morris reveals all that can be done, in terms of pattern, with a group of equals. His only match in this ability is Alexei Ratmansky. (Balanchine, it appears, thought one might successfully do less.) When Morris has lots of people on the stage, the scene suggests impending chaos swiftly and deftly organized into legible phrases. Should this dictate too martial a vocabulary, he introduces and repeats an occasional sensuous step like the Doris Humphrey fall in which the body spirals slowly and smoothly from erect to supine.

Chelsea Lynn Acree (center) with members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in A Choral Fantasy

Chelsea Lynn Acree (center) with members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in A Choral Fantasy

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

But what are we to make of all this? Towards the end, the chorus gets to sing something (vague in the English translation offered in the house program) about love and strength combining to serve humankind’s positive goals. Is Morris suggesting that dance, requiring as it does devotion allied with physical power, is on the side of the Good? As when Twyla Tharp, referring to her early all-female group, called it “a bunch of broads doing God’s work”? Or is he being sardonic about the glory so many people find in the military? This doesn’t sound like the man we know from the other dances he’s made. For me, the point of A Choral Fantasy remains a puzzlement.

The stringency of A Choral Fantasy was counterbalanced by the lushness of Morris’ version of Four Saints in Three Acts, created in 2000 to Virgil Thomson’s plainspoken score, accompanied—and outshone—by Gertrude Stein’s cockeyed libretto (“If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas . . .“). Morris enhanced these givens with Maira Kalman’s faux-naif sets, which evoke a sunlit, blossoming world, and Elizabeth Kurtzman’s pretty, witty costumes.

Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’ Four Saints in Three Acts. Set by Maira Kalman

Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’ Four Saints in Three Acts. Set by Maira Kalman

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Having written about the production on the occasion of its U.S. premiere, this time round I allowed myself to dwell on the most wonderful part of it—Michelle Yard, in the leading role of St. Teresa.

It should be mentioned that Yard is the only black dancer in the current company of 19, and so the role might have obviously been hers in a bow to history; the original, 1934 production of Saints was completely cast with black artists. But Yard, on whom Morris created the role of the contemplative, mystic saint, has seemed irreplaceable from the start because of the warmth and joy she emanates. You feel that if you died and, to your astonishment, went to Heaven, she might be there at the gates to make you feel welcome.

Center: Laurel Lynch and Michelle Yard in Four Saints in Three Acts

Center: Laurel Lynch and Michelle Yard in Four Saints in Three Acts

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Yard is a woman with some flesh on her, so that her technical acuity always seems lusciously cushioned. Over time she’s grown more precise and, with that, more delicate. In this role, especially—and very appropriately—she doesn’t force her presence on the audience; she bides her time patiently until the spectator “receives” her. Of course it helps that she has an irresistibly radiant smile.

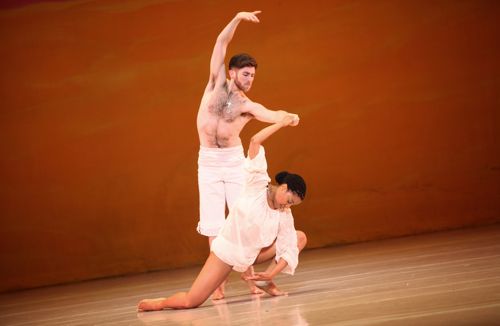

Samuel Black as St. Ignatius with Yard as St. Teresa in Four Saints in Three Acts

Samuel Black as St. Ignatius with Yard as St. Teresa in Four Saints in Three Acts

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Yard is ably complemented by Samuel Black as a solemn, reliable St. Ignatius, and Laurel Lynch stands out—and is given bits of soloist recognition—as the “more equal” of the “Assorted Saints.”

© 2012 Tobi Tobias

Gertrude Stein’s prose was all about rhythm, thus lending itself to musical setting as well as choreography, so I think not so cockeyed after all. Of course it also lent itself to some brilliant parody, to wit, Thurber’s riff on pigeons on the grass, alas, in which he stated that dogs can be on the grass, alas, people on the grass, alas, but pigeons are never alas.

Your prose, Tobi, which is never cockeyed, is also very much about rhythm, and this review is a lovely example of same. Many thanks.

Lovely piece. Did you know — probably you do by now — that last night Michelle Yard tore a calf muscle halfway through “Four Saints”? The show had to be stopped, because there wasn’t any St. Teresa. The curtains came down, the music stopped. Then, after a minute or so, MM came onstage, told the conductor where to restart, and walked off. Rita Donohue ran in, in Michelle’s costume, as if nothing had happened, and the show went on. Very touching. It’s all true about those theater people. The muscle should heal in about six weeks.

Thanks for your report. It evokes some aspects of MM’s recent premiere in San Francisco, for nine men of San Francisco Ballet. It’s called “Beaux,” is costumed in pink camo unitards, and put me in mind of the sadness when soldiers die young. There was nothing to pin this feeling on, aside from the imagery and the tenderness of the dancing, which evoked the tone of Whitman’s poetry — the dear love of comrades, the touch-and-go bonding. It was all about tone — a very elusive tone, which left me almost desperate to experience that again. Many people actively, vociferously, on the spot turned to their nearest friend and said they hated it. Of Morris’ other ballets, “Beaux” most put me in mind of “Robe of White,” “World Power,” and “Socrates.” Of other people’s, “Summerspace” and “Sunset.”

Here’s a link to what I wrote about it: http://www.ebar.com/arts/art_article.php?sec=dance&article=197

I wish you’d seen it; would love to know what you’d have thought.

I miss any mention of the music, played and voiced so superbly by the orchestra (what amazing orchestration!) and chorus. The only problem was the difficulty in hearing all the words in “4 Saints,” which is a fact. And I appreciate the photo of the full backdrop in “Act 1”, of which we in the balcony saw only a few feet.

Your encomium to Michelle Yard is lovely, Tobi. Alas, on Friday night she tore a calf muscle while performing her central role in “Four Saints and Three Acts.” Rita Donahue, stepping in for her, was different yet also marvelous, fleet, innocent without being cloying, and running through minutely calibrated expressive states as easily as if they were pages of a flip book. I’d also like to mention the lighting, by Michael Chybowski, which very subtly turns Maira Kalman’s sets from sun-drenched heavenly here-and-nows to distant memories of the saints’ earthly grin-and-bear-its.

As for “A Choral Fantasy”: I second Martha West’s tribute to your prose; and, having seen the program now, I think you’re onto something. It’s an exciting dance but also, as you say, a puzzling one–and puzzling in the military way you suggest. Mark Morris seems to hear the Beethoven–which, for me, sucks all the oxygen out of the room–as lightning bolts, literally represented by the zigzagging designs on Isaac Mizrahi’s fascinating green uniforms (the Environmentalist Brigade?) and by the dynamic diagonal vectors for many of the entrances, as well as by the asymmetrical phrases, fragmentary groupings, and unpredictable timings. He hears Beethoven as Thor, at least on one level.

But, on another level, there is an alarming, and, it does seem, quite deliberate discrepany between the organic, spiralling experience of the music for any listener and the stylized containments of the severely geometrical choreographic patterns. These are statements, it seems to me, not about the musical work per se but rather about the condition of our earth now as we listen to the Beethoven. And the choreographer’s message, though terrifically energetic, isn’t pretty: There are the Humphrey battlefield falls and what I think of as MM’s characteristically foreboding bourrées in parallel position (in “Four Saints,” they turn the dancers into inanimate objects–possibly the crucifixion structures for the saints?). For the most part, the dancers’ bodies are hammered into vertical slots, without shading to the shoulders or contrapposto. The look, further emphasized by Mizrahi’s uniforms, reminds me of the 1920s Expressionist novels in woodcuts of the Belgian artist Frans Masereel.

Right now–and I’d have to see the dance again, of course–it strikes me as both a tribute to the composer’s galvanizing life force, to his weather, if you will, and also a very ironic essay indeed. I embrace the interpretive option you feel uncomfortable settling for: how far humanity has fallen from Beethoven’s profoundly hopeful and nearly ecstatic worldview. So, Tobi, I think you and I are on the same page about this one, though in different paragraphs.