Weegee: “Murder Is My Business” / ICP, NYC / through September 2; Bill Cunningham: “On the Street” / weekly in the New York Times online

Is it too strange that, seeing the latest Weegee exhibition (subject: violence), I thought of Bill Cunningham (subject: fashion)?

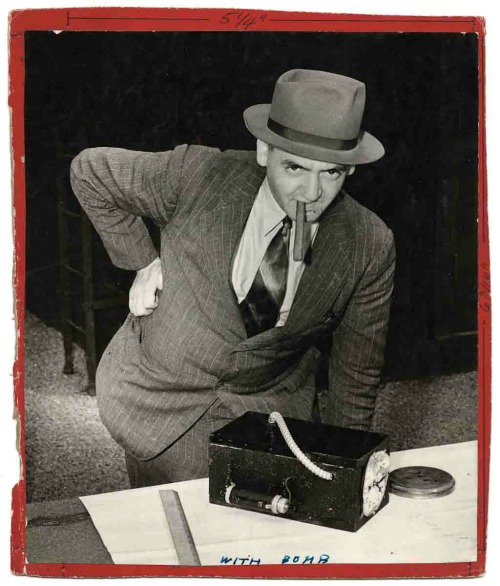

Weegee (the moniker Arthur Fellig gave himself) was, as you may well know, the mid-twentieth-century tabloid photographer who turned his genre into an art form. A retrospective, accurately titled “Murder is My Business,” is at ICP through September 2. Cunningham’s “On the Street” column—caught-on-the-fly photos accompanied by his joyous down-home narration—appears weekly, online, in the New York Times. Richard Press’ 2010 documentary, Bill Cunningham New York, now available as a DVD, offers an extensive view of Cunningham at work and a glimpse into his soul.

Weegee seized his images-in-the-raw by being the first to arrive—sometimes even ahead of the cops—on tawdry scenes of violence in New York’s mean streets. This uncanny instant response depended on canny devices with which he hooked up to the police station across the way from his home base and to fire house alerts as well. His shots of a fallen body sprawled at the weird angles that instant death by bullets provides—grainy images in which white glares at black—seem to have been caught before the blood coagulated. A building being devoured by fire is captured at the peak of its agony, not in the pathos of its fall.

Cunningham’s world is infinitely sweeter, utterly free from pain. It is, perhaps, an antidote to pain. Its landscape is often the Bergdorf Goodman vicinity, the famous outdoor steps (a linear amphitheater) of the public library’s main branch—places for strolling and lounging, not vicious confrontation. His camera captures people we can’t name, who have created their costume for the day with a certain awareness of current fashion’s dictates and a witty, poetic, contrarian attitude of their own. They’re lovely, every one of them, because they are singular, resourceful, and self-aware.

Weegee showed you what the devil can do—creating raw violence that sparks hysterical grief. Cunningham’s delight—in how the man and, especially, the woman in the street seizes the current trends of fashion and vivifies them through personal style—is angelic. Each of them is working at extremes, as if to present—indeed, to communicate—a reality of his own creation.

Each of these photographers was/is married to the idea of authenticity. Each was/is a connoisseur of the world he knew/knows best. Both were/are fueled by unquenchable devotion (call it obsession, if you will) to his subject.

Riding his trusty bicycle, Cunningham reached venues likely to yield a trove of people who activated his imagination or confirmed his vision, and there he trawled for his material. Weegee followed disaster in his souped-up car. Both, responding to need, invented the best way to arrive, a one-man operation, on his subject’s turf.

The living quarters of both photographers were bare-boned, and they both seemed to be unencumbered with family. This is not coincidental ; it is a significant part of what makes their work fascinating. Having a one-track mind requires omitting distraction. If such a mind possesses something that borders on genius, all the better for everyone concerned.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias

Right on! I agree, and I adore the film BILL CUNNINGHAM NEW YORK, though I found sadness in it.

I found the sadness a key part of the film portrait’s beauty. Especially in the passage where Cunningham is asked about his religious leanings and can’t find the words to describe his feelings.

As much as I love seeing and watching Bill Cunningham take his photographs, and indeed, as Anna [Wintour] says in the film, “We all dress for Bill,” whether consciously or subconsciously, hoping we will end up in a photo, I find his view of fashion all too narrow, recording the tastes of a group who are closer to the 1% than the 99%. Of course this is reinforced since Cunningham is the tastemaker in fashion for the NYTimes; what is published tends to confirm the Times’ view of what is fashionable. It is a view of fashion that emphasizes the group-think of what is in fashion, not the real creativity of those who use fashion to present a unique vision of themselves.

Weegee is quite different, I think, since it seems as though he were using these photographs to make his own “film noir” and suggesting that, as a society, film noir is what we are. I feel this is true more and more, that violence is not an extraordinary occurrence but has taken over our lives. For an example, look at the video of the Occupy demonstrator in Washington, D.C., who was tasered today.

I agree with Tobi that these are very insular men, recording a chosen and perhaps outlandish world, but their choice of subject and their methods reinforce their alienation. Nonetheless, what I really feel is missing is their uncensored voices: Which photos would Weegee have chosen, given free rein? Which photographs would Bill Cunningham choose if he could publish anything he wanted? Is this their last word? I think not.

.

Aloha, Tobi! Much enjoyed your thoughts on these polar opposites, one of them well known to me, one of them not. I’ll let you guess which is which. Clues: two articles of mine from the Smithsonian Magazine archives, one about a photo called A Day at the Beach (http://bit.ly/wTSYPn), the other called The Critic (http://bit.ly/xeuzTz).

Hello, Tobi,

This is a beautiful piece, and what a stroke of genius to treat the two together. Yes, indeed. Only you would have thought of the pairing. I much prefer the angelic vision.