New York City Ballet: All-Wheeldon program / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 28, 2012

He started out as a prodigy. He got better and better at what he was good at: the architectural organization of a dance; the seamless incorporation of non-traditional dance movements into the classical matrix he had inherited; a deep understanding of the partnership of dance and music.

Born in England in 1973, Christopher Wheeldon began studying dance at 8, entered the Royal Ballet School at 11, and graduated into the company at 18. His career as a dancer was all smooth—and swift—sailing. He copped a Gold Medal at the Prix de Lausanne, then, at 20, left for America to join the New York City Ballet. There he rose to the rank of soloist, all the while creating ballets for that company. In 2001, having retired from performing to devote himself to creating dances, he became City Ballet’s Resident Choreographer, a position created for him. Good fortune continued to smile upon him. The first ballet he made in this position was Polyphonia, which remains one of his finest achievements. It wasn’t long before major classical companies in Europe as well as the States were requesting a new ballet from him, a state of affairs that, much intensified, prevails today.

By 2007 Wheeldon had moved on to his next venture, creating a company called Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company that was intended to revivify ballet in some sort of Diaghilevian way, involving the collaboration of artists from different genres. Youthfully outspoken at that time, Wheeldon said some unfortunate things about Balanchine, which won him no friends. Far worse, he abandoned this group in 2010, dissatisfied with its demand on his time and its inability, as a pick-up company, to offer him a steady group of dancers. This move looked like desertion. Wheeldon, with so much sunny experience behind him, lacked the patience required for the slow development of a ballet company. (The group, under the direction of Lourdes Lopez, Wheeldon’s associate for practical matters in the formation of Morphoses, is attempting to continue the company’s life without Wheeldon’s participation or name. And with a markedly different agenda.)

Wheeldon’s success as a free-lance choreographer is rivaled only by that of Alexei Ratmansky. He makes every kind of ballet imaginable, although, to my mind, his finest works by far are shorter pieces (one-acters, so to speak) that are abstract, sometimes with a subtext of mood or even story, sometimes not. His 2011 Thirteen Diversions for American Ballet Theatre showed him still advancing steadily in complexity and sophistication, as well as attempting to have his choreography do what it had never yet done (to the disappointment even of his most enthusiastic fans): evoke stirring emotional life.

On January 28, City Ballet honored Wheeldon by presenting a one-man-show of his work. The occasion was the annual New Combinations evening; the ballets were Les Carillons, in its world premiere; Polyphonia, perhaps still his best ballet, more than a decade after its creation; and the 2006 DVG: Danse à Grande Vitesse, in its company premiere.

Polyphonia showed Wheeldon poised on the verge of a remarkable choreographic career. The ballet could have been called What I Learned From Balanchine and Where I Can Go From There. The references to and fleeting direct quotes from the master come largely from the “leotard ballets” that lie at the heart of Balanchine’s aesthetic and seem to reveal the workings of the universe.

Wheeldon’s opening, for example, refers to the opening of Agon. Where Balanchine used a horizontal upstage line-up of four men working in canon with dazzling clarity, Wheeldon places the four couples who constitute his full cast in the same position to create a whirlwind of limbs until they settle down into unison. The full cast doesn’t appear again until the finale; in between, duets, a trio, and a quartet—with solos embedded in them—demonstrate an outsize skill in arrangement.

Like Balanchine, Wheeldon understood the marriage of dance to music and made an astute choice for Polyphonia in the sharpness and delicacy of ten piano pieces by György Ligeti.

Essentially the ballet is a statement about Wheeldon’s roots—here Balanchine, in other ballets Robbins, Ashton, and MacMillan. Wheeldon has always seen the “greats” as mentors. But as befits an ambitious young choreographer, Wheeldon uses Polyphonia to challenge the master as much as to pay homage to him. To take the tiniest but still revelatory example, Wheeldon concedes to Balanchine in clothing the dancers in austere classroom uniforms, even to the narrow leather belt girding each woman’s waist, but he replaces the customary black—in the leotards for the women and both t-shirts and tights for the men—with a rich, aubergine-tinged brown. So many years after he scored that deft little point, it still makes me happy.

Midway through Polyphonia, Jennie Somogyi, one of its principals, sustained a major injury to her right ankle, later diagnosed as a torn Achilles tendon, a disaster that has ended the careers of many a professional dancer and athlete. She managed to walk—hobble, really, in obviously tremendous pain—the long path between the glaringly lit center of the stage and the dark shelter of the wings, to allow the ballet to continue. Continue it did, with an empty space where Somogyi belonged, until Tiler Peck gallantly came in to replace her. Somogyi’s courage and grace, despite her pain and foreboding—she had already made a long, heroic recovery from the same injury to her left ankle in 2004—are qualities that make dancers mythic. I wish her the favorable outcome she deserves.

DGV: Danse à Grande Vitesse—which takes its name from the super-swift trains (TGV) that transformed tedious journeys into quick commutes—reveals qualities that are the very opposite of Polyphonia’s. It is so showy, hollow, and poorly organized, you wonder if the same guy could have produced the two. Actually, it made me think of Benjamin Millepied’s work in the grandiose vein.

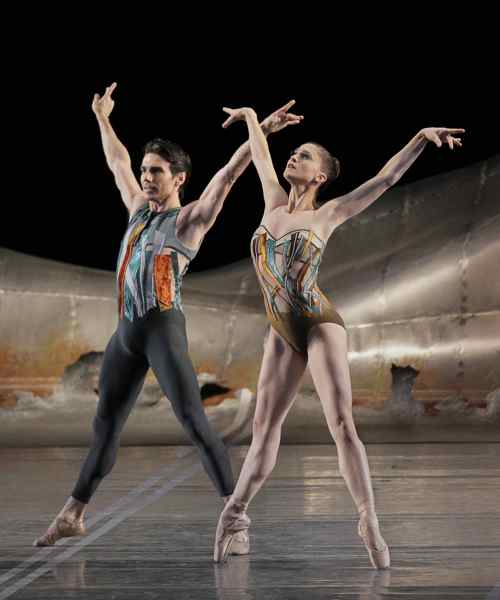

It’s performed to a Michael Nyman score, MGV (Musique à Grande Vitesse), heavy on drums, that basically sounds and functions like movie music and makes what’s essentially a one-acter feel as long as a main-feature film. The set, by Jean-Marc Puissant, who also created the jittery-looking costumes, causes even worse trouble. If Wheeldon was determined to choreograph a ballet about the thrill of high speed, why did he have his designer occupy a huge part of the stage? Speed needs space. Otherwise it’s just running in place.

Puissant stretches an attention-stealing wrecked train horizontally across the stage. In its viciously crumpled titanium magnificence, it’s handsome indeed, and clever too (becoming translucent after a while and providing entrance and exit stations—inhospitable though they are—for the dancers). Does the threat of disaster make high-speed travel more exciting? I guess so, but that train is as obtrusive as the Santiago Calatrava sculptures were for every choreographer who used them in City Ballet’s dismal Architecture of Dance festival of 2010.

The ballet is divided into two parts—first day, with night (and dreams?) succeeding it. Choreographically there wasn’t any telling difference between the two. Most often the stage looked like the rehearsal site of a Broadway musical that had lost its way in a series of out-of-town try-outs. It did at times show off City’s Ballet’s highly evolved technical prowess, though it was sometimes lost in the relentless maelstrom of activity. I managed to appreciate the work of Maria Kowroski, spinning a spider web of delicate designs as she was sympathetically partnered by Tyler Angle, and the high spirits of Tiler Peck and Andrew Veyette in an energetic duet. Teresa Reichlen, because of her marvelous height and security in balance, looked like an icon assuring the populace that, even amidst tumult, things needn’t fall apart.

And then there was the newly created Les Carillons, It’s set to Bizet’s L’Arlésienne Suites Nos. 1 & 2, with which we’re already too familiar. The ballet seems to be informed by the qualities conventionally associated with the Spanish soul: pride, passion, and patriotism unto the death, to begin with.

Wheeldon certainly shows off his organizational expertise in this piece while the music is allowed to dictate fluctuations in tone. The segments vary gracefully among populations of different sizes and configurations. Four dancers peopling a sequence, for instance, shift silkily, again and again, between being two couples and coalescing as a quartet. Symmetry and asymmetry are often part of the same stage picture, an effect tricky to bring off. But at no point are we clear about who’s who, the specific temperament of individuals or groups, or what they’re trying to accomplish.

As happens so often in a Wheeldon ballet, Wendy Whelan’s incandescent presence drives other figures into the shadows and she mesmerizes the audience simply by becoming a hypersensitive body folding and unfolding. Here, after this is accomplished, a crowd returns to surround her and she threads her way through this human maze like a lost maiden in a legend or, perhaps, a fragile young woman—you read about them in the newspapers—unable to cope with the rigors of contemporary urban life. Sara Mearns makes just the right foil for her. She’s all womanly power, boldly devouring space, laying claim to it as her own. Astutely partnered by Craig Hall, who is not intimidated by her largesse of body and spirit, she’s also spectacular on her own. And so it goes, but sooner rather than later, the viewer will start to wonder what point the piece is trying to make. One among such spectators, I concluded unhappily that there was no discernable point.

Mark Zappone’s costumes, presumably aiming for tasteful flamboyance, were too lavish, as the outfits for Wheeldon’s ballets became the moment he had a generous budget. The stage was flooded with jewel tones, the skirts of the women’s dresses were too full and too heavy-looking, and the men seemed to be outfitted as look-alike suitors. Many observers might have found this wardrobe handsome, but none of the intermission talk I heard had a good word for Puissant’s backcloth, an abstract display in peach, sienna, and shades of gray, which put me in mind of an expiring fire.

So what are we to think about Wheeldon’s future? Will he build on the progress he displayed in last year’s Thirteen Diversions for ABT? Or are the problems of his most recent work likely to resurface? When you’re as gifted as he is, it must be tough to hear that you’re still not good enough.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias

A choreographer goes through different periods, much like a painter. Every dance is part of a larger process, just as Picasso went through his blue period or Matisse turned to cut-outs. An unsuccessful piece of choreography may be the darker side of a group of works about to emerge with more clarity and wit. I hope Christopher Wheeldon finds the support and the environment he needs to create. Or maybe he will become accustomed to the difficult road as it is and surprise us with his next body of work. Perseverance furthers.

In response to Catherine Turocy: Perhaps. But sometimes inspiration dries up — see Antony Tudor. My own feeling is that Wheeldon will not fulfill his early promise.

You are a marvel!. You describe the essence of what you see accurately, creatively, and soulfully. Your reviews are always so articulate and descriptive, the reader almost feels as if s/he were at the performance. I hope you derive as much satisfaction from what you write as you give to others like me.

Rob Daniels, New York City Ballet’s Managing Director of Communications and Special Projects, writes:

”Just read your ArtsJournal post on Saturday night’s Wheeldon program and thought you would want to know that the current injury to Jennie Somogyi’s right foot is not the same as the injury she sustained on her left foot in 2004. The 2004 injury was to the posterior tibial tendon, and the current injury is to her Achilles tendon.”

“A choreographer goes through different periods,much like a painter,” is an interesting comment from Catherine Turocy, though this longtime observer of both choreography and painting would like to amend it to “some choreographers go through different periods, much like some painters,” for I’m damned if I can figure out different periods of Balanchine’s work or my artist father’s either. It’s a handy kind of pigeonholing that arts writers, of which I am one, do, but I’m not sure it’s really valid. And how do you categorize them, anyway? By palette as in Picasso’s “blue” period (and actually blue paint was the cheapest available when he was young and very broke in Paris), by composer, in the case of a choreographer, like Stravinsky for Balanchine? Is “Firebird” like “Agon”? I don’t think so.

As for the subject of this review, he’s obviously a fine craftsman; there is nothing disorganized about any of the work I”ve seen, including his Degas-infused “Swan Lake” commissioned by the Pennsylvania Ballet, and “Polyphonia” is a lovely piece. The man is still quite young, and still searching, and he has a right to fail. I don’t know that City Ballet has served him well by programming an all-Wheeldon evening; I wasn’t there, except to the degree that TT invariably puts me there with vivid, thoughtful writing.

Having been present in the theater when James Canfield put paid to his dancing career by tearing his Achilles tendon (I actually heard it–it was awful) I’m very sorry to know that Ms. Somogyi has injured hers and I fervently hope it will mend. She’s a lovely dancer.

I don’t think you can say Christopher Wheeldon deserted Morphoses. Every time I heard him speak about it, he emphasized that it would NOT be a pick up company. Yet that is what it was. My feeling is Lourdes [Lopez] DID NOT do HER administrative/fundraising job well. She should have been to Wheeldon what [Lincoln] Kirstein was to Balanchine; she wasn’t. Unless Wheeldon wanted to go down with a sinking ship, the painful but right choice was to resign.

Unlike dancers, who learn much of their craft in the relative privacy of the studio, choreographers learn how to make dances in public. There are very few times that a choreographer can make a dance and then put it away without presenting it. Good dances and bad ones (the latter often the most instructive) — almost all of them will wind up in a performance somewhere, and we will see them.

True, Sandi, true, but I also thought as I read Tobi’s review, that we more easily forgive or over look the failings of people we also find likable and it made me wonder if there wasn’t something that rubs the wrong way in Wheeldon’s work or personality. As I’ve never seen it, I don’t have an opinion, just a suspicion.

I’ve been meaning to look up the myth of the Arlesienne and where it came from. Before I did my homework, I knew she was considered an important mythic figure in the Provence, around Arles, and also that Christian Lacoix dedicated a couture collection to L’Arlesienne.

As a result of Wheeldon’s ballet, I looked up l’Arlesienne and discovered that in general the reference is to the play that was taken from Alphonse Daudet’s stories “Lettres à Mon Moulin,” which has a story about L’Arlesienne. The music for the play is the Bizet music that Wheeldon used, with additions later on, for his ballet “Les Carillons.”

In the story and play, it is an absent woman who is the basis of the tale. The absence alludes to the Venus of Arles, discovered in 1651 in the ruins of the antique Roman theater in Arles. She was missing an arm, but she was a beautiful Greek statue, probably based on an earlier statue by the great Greek sculptor Praxiteles (French spelling). At any rate, she immediately generated great local enthusiasm, so everyone was pissed when Louis XIV commandeered her for the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and promptly restored her missing arm and nose. She stayed at Versailles until 1797, when the Louvre got her. At any rate, there is a very early copy in Arles, but Arles has never managed to get the Louvre to return the original, except as will happen next year, for an occasional exhibit.

This also generated a myth around the beauty of women from Arles. Even Stendhal, whose love of Italians was well known, found the Arlesiennes particularly beautiful on his trips to Marseilles and Provence: white skinned, with intensely black hair. The Venus d’Arles is more refined in her body, thinner, and not as bodacious, for example, as the Venus de Milo, who came to France in the 19th century. So in a sense she incarnates a quintessentially French ideal of beauty, particularly that of the area that is the cradle of classical Roman France.

And of course, Lacroix, who is from Arles, as I remember, would also be aware of this myth and its artistic and literary history. When Gauguin and Van Gogh were in Arles they also made paintings known as “L’Arlesienne.”

I think you see all this in the ballet — not just the music, but the costumes and the backdrop. I found it very evocative, recalling memories of Arles and how much I loved it. The ballet was beautifully danced and wonderfully evocative of the light and intensity of Arles. It is a ballet that I think will age well.