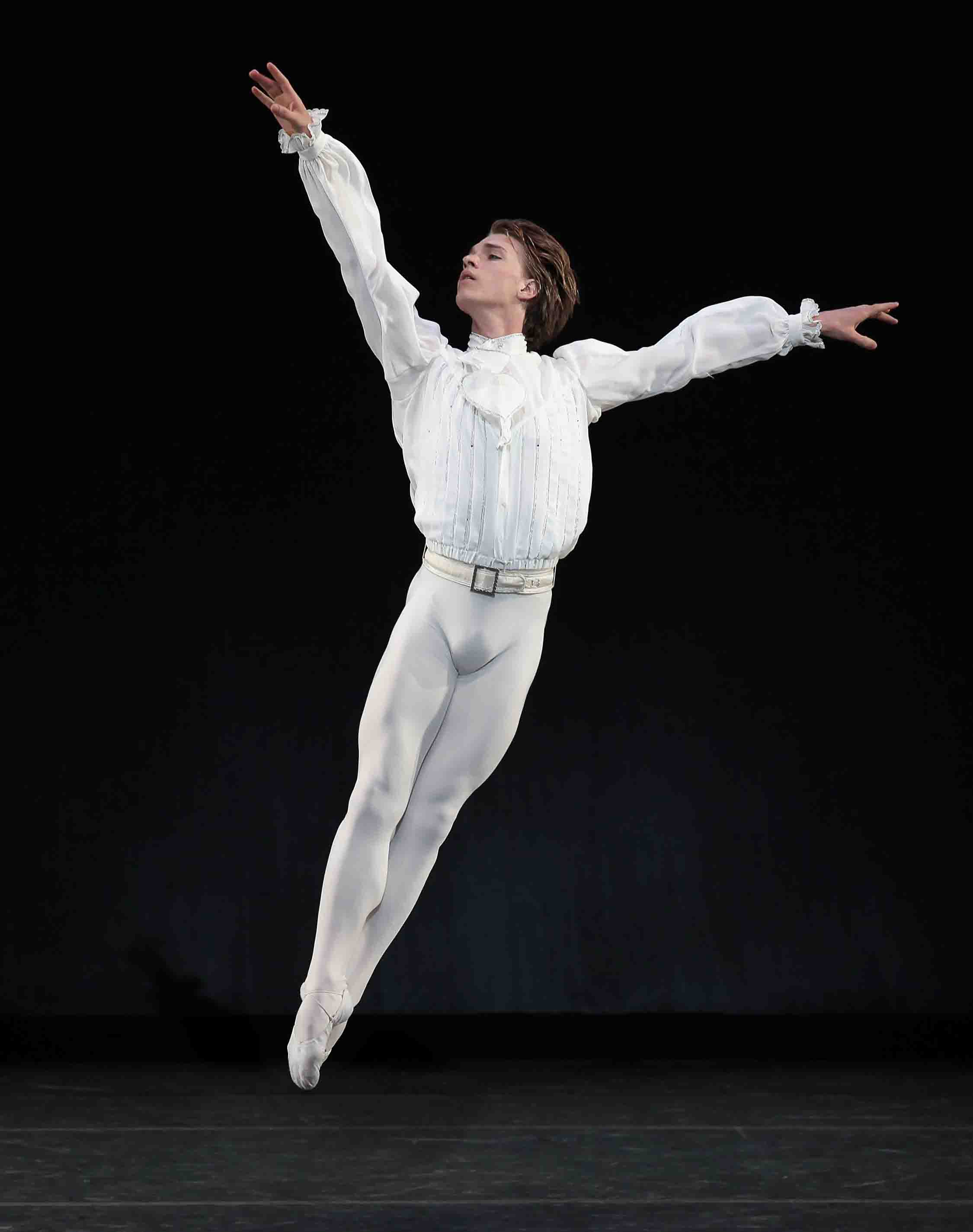

American Ballet Theatre: Jose Manuel Carreño’s farewell performance / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 30, 2011

Jose Manuel Carreño bowing to the audience at the close of his farewell performance with American Ballet Theatre

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Is any dancer among us today as much loved as Jose Manuel Carreño? The ardor was apparent at American Ballet Theatre’s June 30th performance of Swan Lake at the Metropolitan Opera House. The occasion was the company’s official farewell to the 38-year-old star playing Prince Siegfried who has been one the pillars of its fame. Yet the evening seemed not so much a regretful goodbye on the part of the dancer and his audience as a celebration of Carreño’s artistry and the personality that informs it.

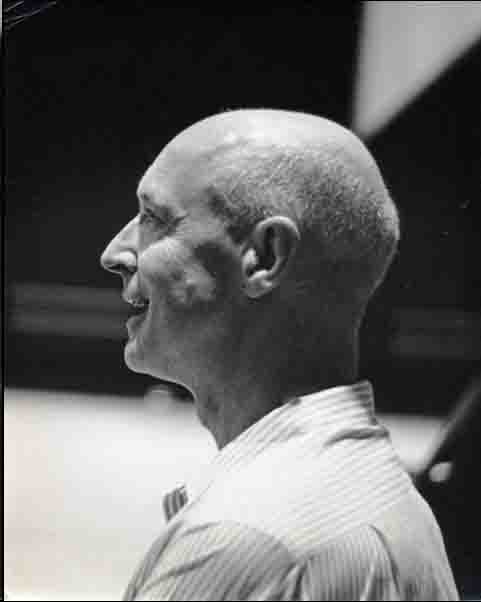

A brief bio is in order. Born and trained in Cuba, Carreño joined the National Ballet of Cuba headed by the legendary taskmistress Alicia Alonso. After winning a couple of major international competitions, he moved on–to the English National Ballet in 1990, then to the Royal Ballet in 1993. Gradually he realized that, despite all he learned from these opportunities, he and England were ill-matched–the people too buttoned up, the weather too gray–and joined ABT, where he has danced to continuous acclaim since 1995.

Since then, I’ve seen dozens of his performances and can report this about them: The moment Carreño appeared onstage, you sensed his warmth, his erotic appeal, his unquenchable joy in dancing, his generosity, and his impeccable manners. Just a few minutes into the proceedings, his remarkable physical prowess had you gasping. The showiest aspect of it comprised astonishing feats made to look like a form of exuberant self-expression, not, as occurs too often, the material of a second-rate circus. Carreño’s technique was clear and correct yet still sensuous, innately musical (rhythm ran through him), and wedded to harmony of line. Longtime fans have been talking, too, about how, even as the bravura capability that first got him noticed inevitably began to fade, it didn’t matter much for a while, and, when it did, he decided to take leave of the company that had been his home in his physical heyday.

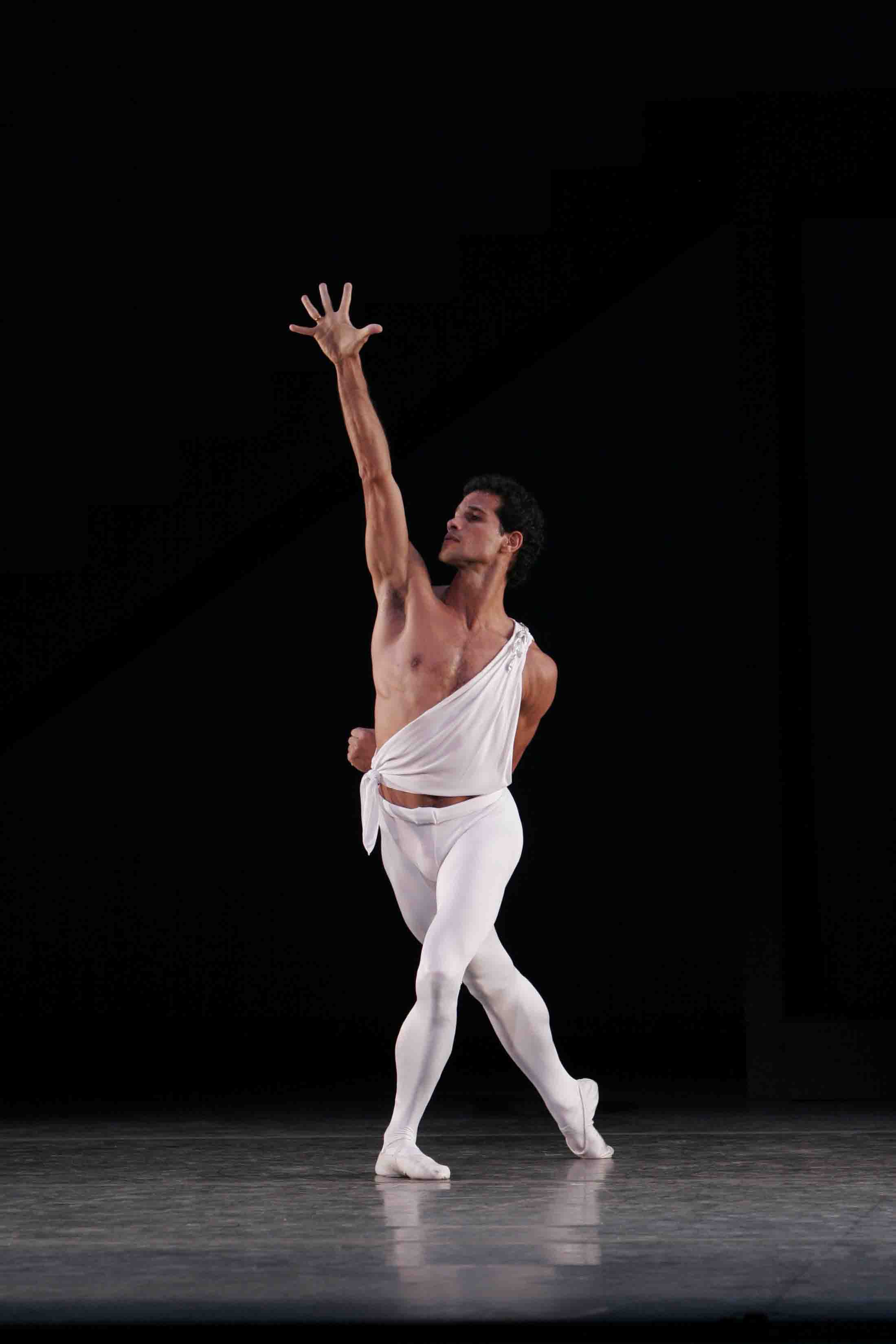

Carreño in the role his fans most identified with him: Basilio in Don Quixote

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

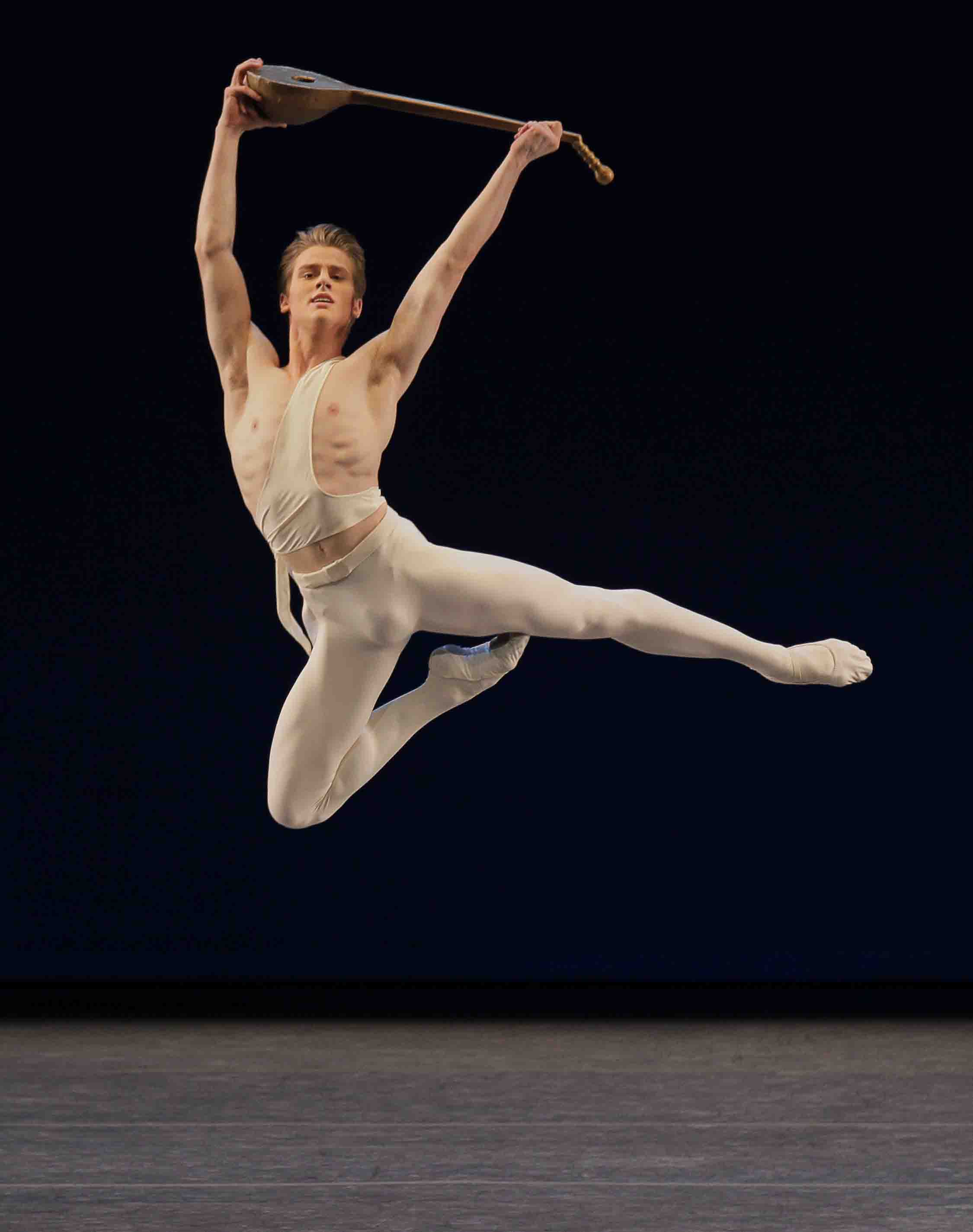

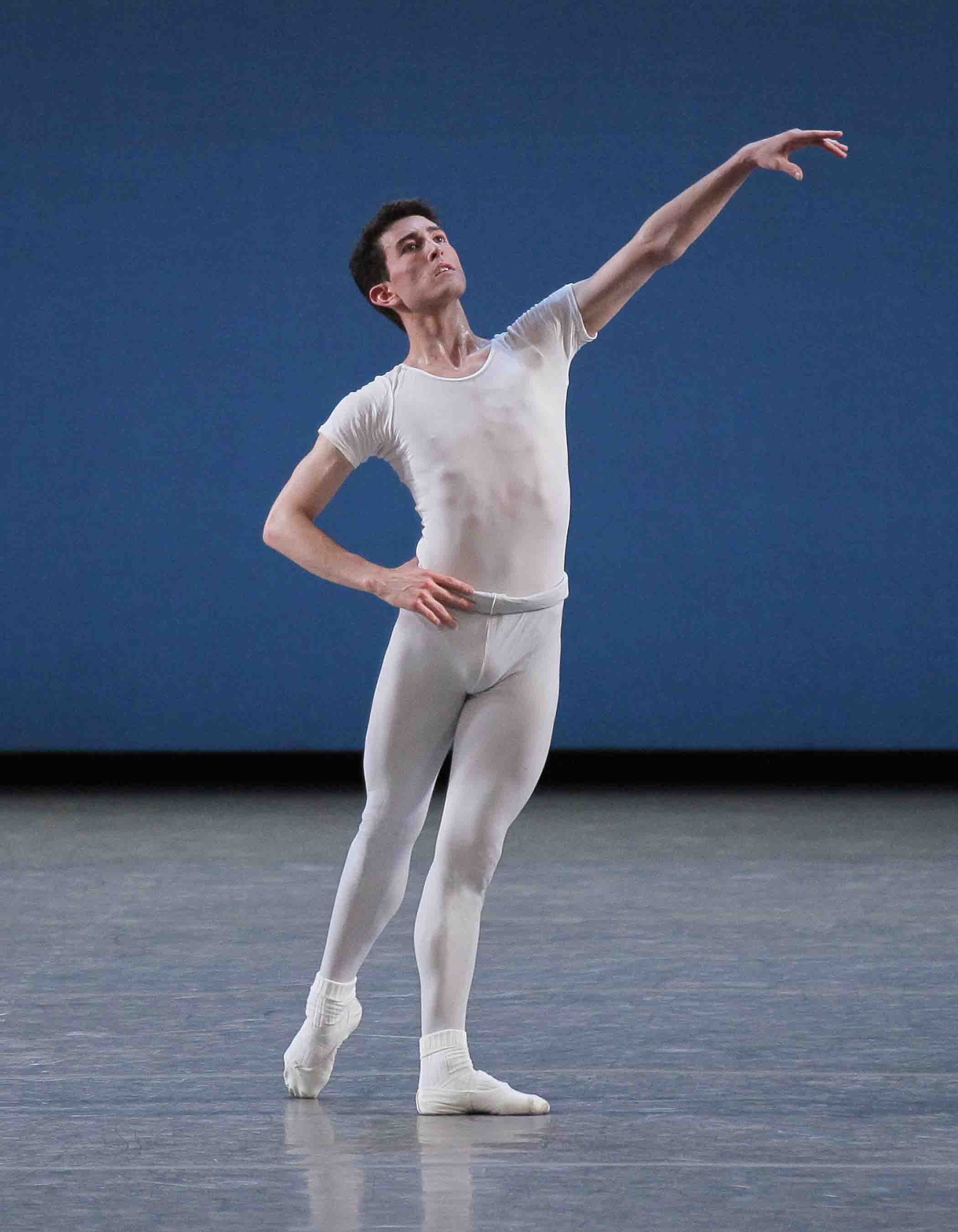

Carreño performing the title role in George Balanchine’s Apollo for ABT

Photo: Marty Sohl

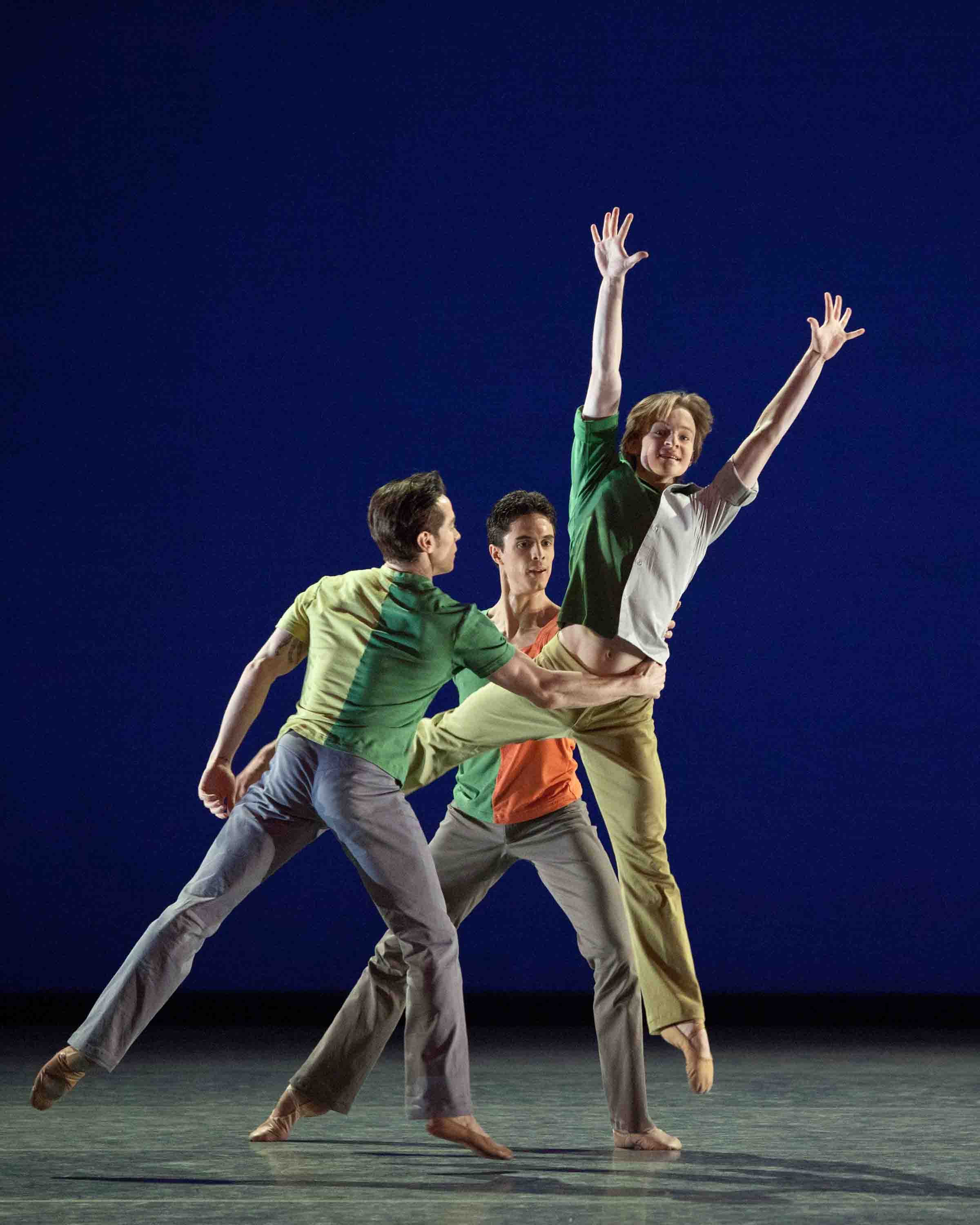

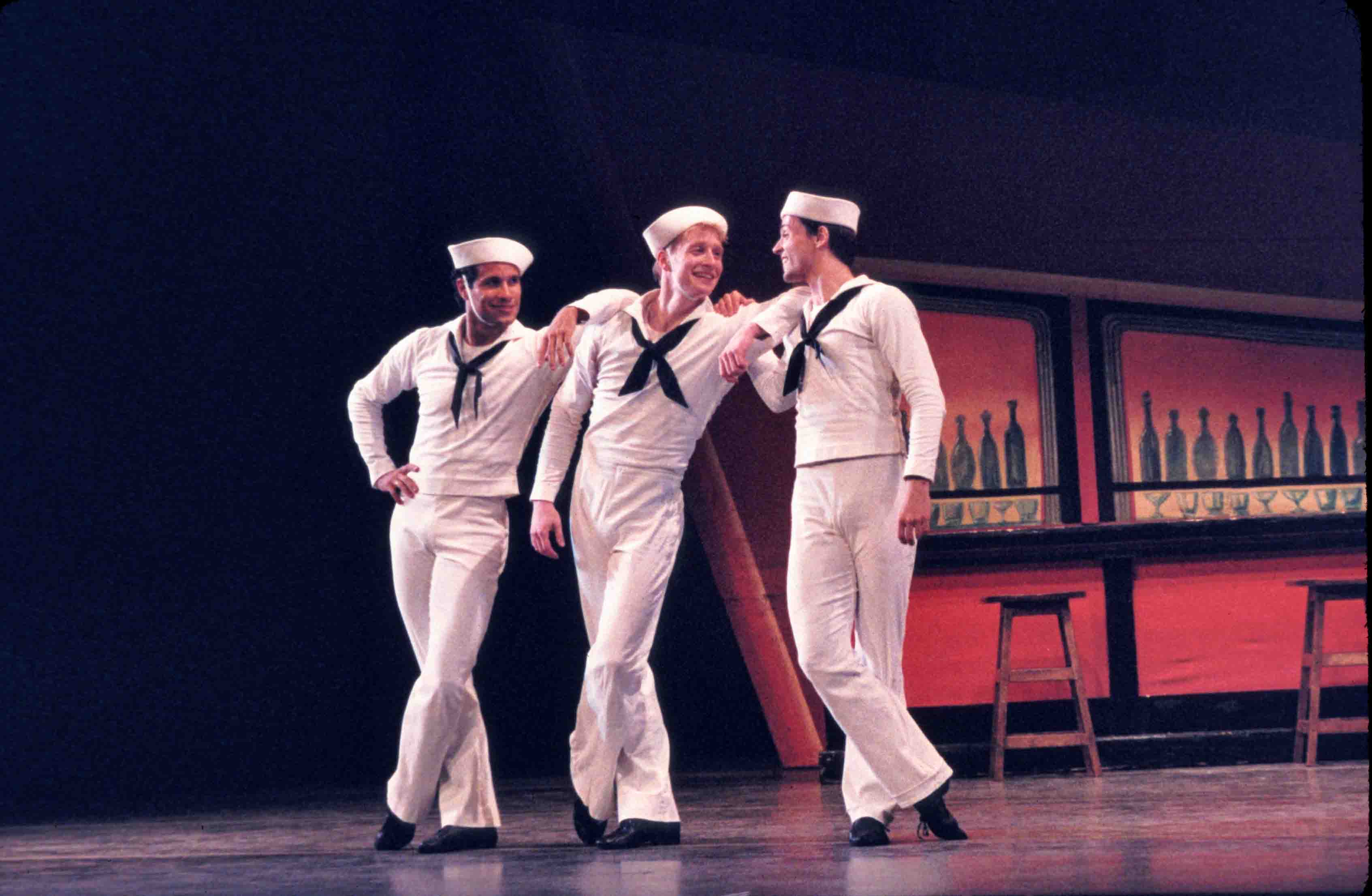

From left: Carreño, Ethan Stiefel, and Angel Corella in Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free

Photo: MIRA

Carreño has been wonderful in both classical and contemporary roles. He’s played just about all the danseur noble roles in the international repertory, from Albrecht to Apollo, and was equally comfortable in the more slangy styles of Jerome Robbins and Twyla Tharp. If classical ballet, 19th-century style, didn’t convince a viewer that Carreño was terrific–and a heartthrob, to boot–this resistance would likely be overcome by his performance in Robbins’s 1944 Fancy Free, which charts the adventures of three sailors on leave in New York. He played the part Robbins created for himself, the guy who does the sexy rhumba with the chair.

As many a grateful ballerina has attested, Carreño has also been the ultimate cavalier, infallibly gracious to his partner, whoever she might be. It’s as if “Woman” were a generic character in his stage life, eliciting from him an instinctive response of deference and devotion, to say nothing of astute partnering.

Despite the fact that farewell performances often require the audience to take on faith the best achievements of the honoree, Carreño’s was thrilling in and of itself.

He was surrounded by friends. Two of his most frequent partners split the leading female role between them, as has occasionally been done in the past, to tailor the technical challenges to each ballerina’s specific gifts. Julie Kent was the epitome of poignant regret and fragility as Odette (the white swan); Gillian Murphy, a voluptuous, witchy daredevil as Odile (black). Susan Jaffe, a third ballerina with a long history as Carreño’s partner, came out of retirement to play the Queen Mother. Cast as Benno, Joachim de Luz–a close pal from earlier ABT days, who’s now with City Ballet–added sparkle to the Act I pas de trois. Melanie Hamrick, Carreño’s fiancée (as was recently announced in the New York Times) was featured in the Spanish Dance and as one of the two swans who do the weighty mirror-image adagio passage that underlines the swans’ communal sorrow. In truth, though, it seemed that the entire company was working as a united force to make the performance as splendid as Carreño deserved.

Carreño himself danced the way, perhaps, he dreams of dancing; everything worked, his gifts and his current abilities coalescing. He nailed each of his solos. The virtuosic demands were well considered, ably met, and finished with neat, cushioned landings, while Siegfried’s melancholy solo when he feels alone and loveless in a crowd of his paired-off friends, was handsomely sculpted and beautifully acted. Performances like this come only rarely in a dancer’s life, and usually at a poorly-attended matinee on a rainy Sunday. Here, with some 4,000 pairs of eyes fixed on him alone, there were many passages that must have made the spectators wonder why the guy was retiring at all.

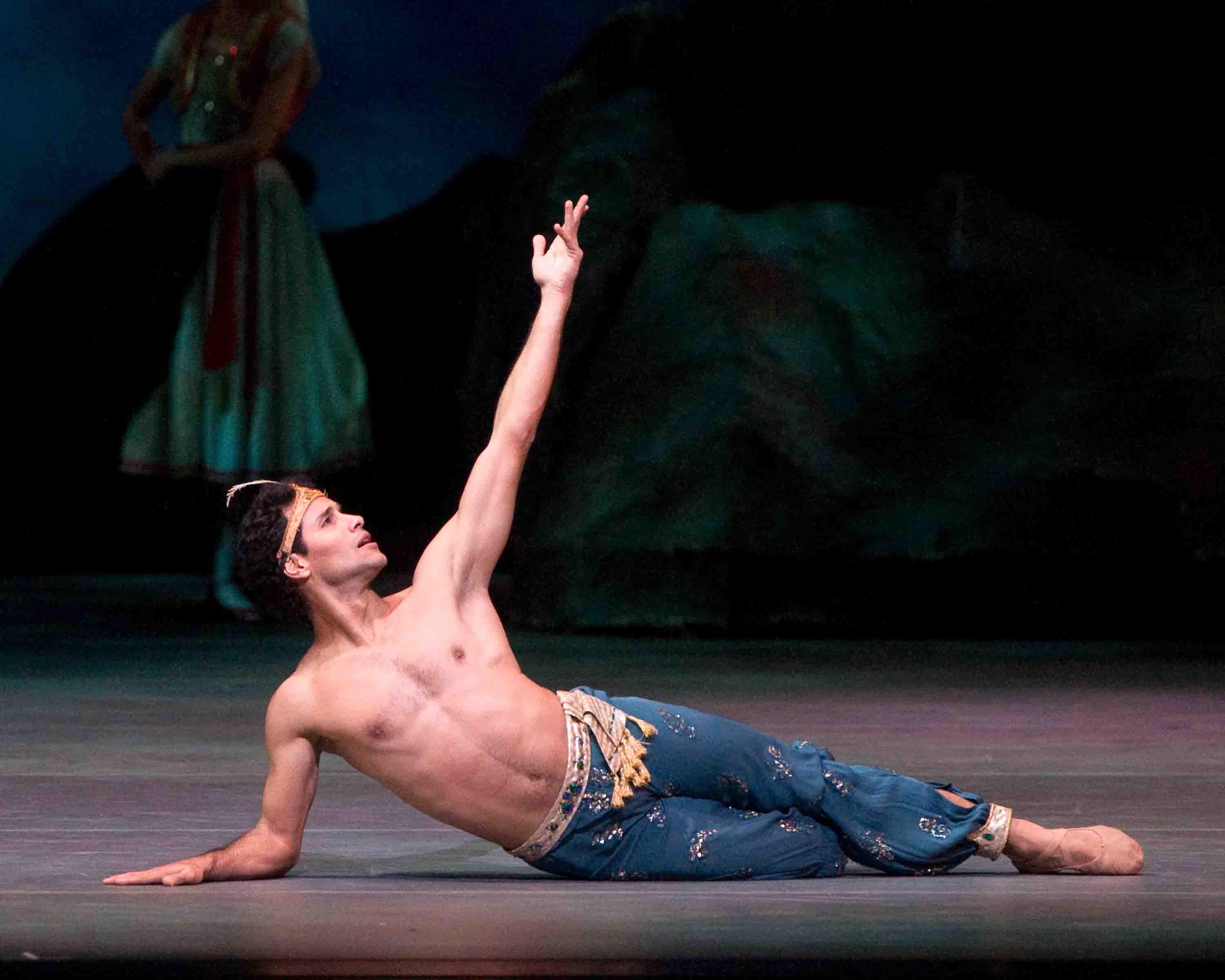

Carreño and dancers of ABT in Le Corsaire

Photo: Gene Schiavone

True, his leaps these days are not what they once were. They’re softer in attack and lower at their peak. Still, now as well as back then, for a dancer who always seemed so much more of-the-earth than most danseurs nobles, he appears very light in the air–not ethereal, but simple very light, as if gravity had reduced its claim and the air itself made him buoyant.

Turns are Carreño’s specialty and his continue to be unsurpassed in their finesse. Throughout his ABT career, as I recall, he was in the forefront of inventing variations on multiple pirouettes–as with the working foot poised at the knee of the standing leg and then, with a barber-pole effect, stealing down the standing leg to hug the ankle. Lately, while still swiveling smoothly, he can make the working foot sneak upward again. He can also diminish the speed of a multiple pirouette so that it starts out ferociously energetic and finishes in a contemplative calm. Such inventions, adopted by his peers and the rising generation of standout men, enliven and enrich the ballet vocabulary though they occur so naturally, we hardly notice them.

Time has only enlarged Carreño’s adroit partnering skills. In terms of physical support, he’s keenly sensitive to what his ballerina needs, how much, and when. At the same time he builds an emotional rapport between her character and the way she’s playing it and his. Everything he does is governed by a self-effacement that seems to be central to his temperament. Though his stardom is indisputable, he tempers it with humility.

Carreño in his farewell performance with ABT, dancing Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake with Julie Kent as Odette

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

In his response to Kent’s Odette, he gauged his presence and held back in intensity. He was never not there, but he never overwhelmed her. The music for their lakeside pas de deux was taken at so slow a pace–presumably requested–that it provided a gossamer surround for the ballerina’s fragility. Carreño performed as if the character Kent had devised for herself were the most important element in the ballet–as if, indeed, he’d forgotten to whom the evening was dedicated.

Carreño in his farewell performance with ABT, dancing Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake with Gillian Murphy as Odile

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

With Murphy, he matched both her physical challenges (which were spectacular, such as triple fouettés enlivening the obligatory 32 singles) and the nearly excessive excitement with which she played the temptress. In their pas de deux he even smiled for a few seconds like someone having an indecently good time; then let some doubt that Odile was his beloved Odette shade his face; next quietly and sweetly surrendered himself to Odile as her prey. Given the mounting incendiary quality of their match, the firebomb explosion when the villains’ duplicity was revealed seemed a crude afterthought.

Some of the wonders Carreño worked were very small and subtle, yet they registered large as moments charged with meaning–and magic. An example: At one point Siegfried is searching, futilely, for Odette among the lamentation of swans; then she enters the stage from behind him and he seems to feel her presence at the nape of his neck. Carreño’s expression of Odette’s effect on him–simply through her being near him, before he turns his head to see her–is an effect I’ve witnessed only in classical Japanese theater. I’ve seen it attempted in Giselle of course, but never convincingly.

From Carreño’s farewell performance with ABT: Carreño (center, with bouquet); to his left, David Hallberg; to his right, Kevin McKenzie, ABT’s artistic director

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Then, the bows, always the final act of such an occasion. As the curtain fell on Swan Lake the spectators in the packed theater rose as one, applauding and shouting their acclaim. First the full cast, much of it in white feathers, bowed. Then the dancers of the solo parts, and then the principals: David Hallberg who’d been spectacular as the licentious von Rothbart (a dancing role in the current ABT production), then Carreño and his two ballerinas.

As the sequence was repeated, Carreño kept the pair of ballerinas by his side as long as he could before he allowed himself to take a solo bow. Needless to say, it elicited roars from the house. Murphy and Kent had retreated to the sides of the stage and, with the rest of the cast, were applauding Carreño who, turning his back toward the audience, knelt and bowed his head in homage to the company.

While all this was going on, red and white flowers were hurled from the heights of the auditorium and flung over the orchestra pit. No sooner had a more formal presentation of tributes concluded than a parade of Carreño’s colleagues marched onstage from the wings, one by one, to deliver embraces along with their own floral offerings–so many that the bouquets and laurel wreaths had to be laid to rest on the floor, where the petals and leaves, gently crushed, formed a mound of tribute.

After another round of bows for the principals in front of the Met’s iconic golden curtain–mind you, the applause went on steadily for some 15 minutes–Carreño, by now weeping between smiles, took his last bow, one arm around each of his lovely, raven-haired teenaged daughters. No confetti. No helium balloons. They’d have been a frivolous distraction at an event that anatomized devotion.

ABT’s Jose Manuel Carreño in the company’s production of Le Corsaire

Photo: MIRA

Carreño’s future in dance is assured. He talks about the possibility of guest appearances with ABT and beyond. He’d love to perform on Broadway or in film. He is also already celebrated as a teacher, working with the boys at the School of American Ballet (New York City Ballet’s academy) and giving company class at ABT. This summer he’ll offer a comprehensive summer program for the young, the Carreño Dance Festival, in Sarasota, Florida. Perhaps he’ll have more time for some favorite diversions: playing tennis, exercising his salsa chops in the clubs. We won’t see as much of him, but we’ll never forget him.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias