Fall for Dance / City Center, NYC / October 27 – November 6, 2011

The price of just about everything is escalating–food, college, shoes, diamonds, you name it. Yet one thing in New York has kept to its bargain rate. Tickets to the annual Fall for Dance festival at the newly refurbished City Center are still just $10 each. From October 27 through November 6 this year the Festival has offered two performances each of five different shows, each of them contrasting four soloists or groups of very different stylistic persuasions. Dance veterans and newbies beware: You’ve got to be quick on your feet in buying your tickets since Fall for Dance is famous not just for its range and affordability but also for its sold-out houses.

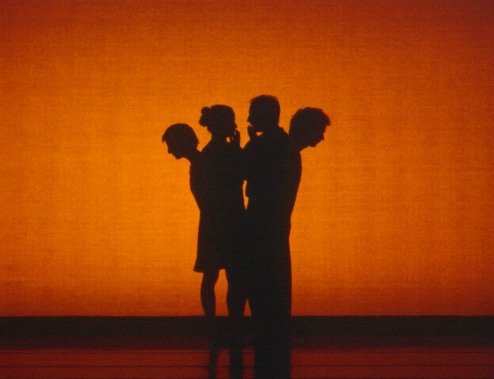

Last night I saw the first program, which presented the Mark Morris Dance Group, Lil Buck, the Trisha Brown Dance Company, and the Joffrey Ballet. The evening opened with Morris’s 2003 All Fours, set to Bartók’s String Quartet No. 4, played live. Admirably, Morris insists on this condition and is willing–and, thanks to his success, able–to pay for it. Essentially abstract, the dance appears to pit two communities against each other, then bring them to an uneasy reconciliation. The groups are identified by the color of their costumes; there are eight “blacks,” four “whites.”

Profiled: Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’s All Fours

Photo: Ken Friedman

The black crowd might be a gang possessed by evil, brain-washed into it perhaps, and ready to disseminate it, or so I assumed from the mechanical, staccato quality of their actions. The white contingent may remember what love is, but obviously harbors a deadly secret (indicated by their cautionary gesture of raising their fingers to their lips). It comes as no surprise that Morris never reveals what the secret might be; doing so would ruin the work’s power. Paul Taylor operates with the same splendid motto: Never explain.

The rapprochement of the two contingents isn’t rendered as clearly as their earlier opposition, which is presented as turf warfare. Once the two gangs tentatively start occupying the same space, it’s hard to tell what might have brought them together. But then compromise is never as clearly dramatic as contention.

The choreography is full of astute references to other legendary modern dance choreographers. From Martha Graham Morris co-opts the pleading or praying gestures of folks in trouble; from Paul Taylor, the lumbering gait of the grotesques in 3 Epitaphs; from Doris Humphrey, the most gorgeous of the falls to the floor that she invented: from vertical to splayed-out supine on a single count.

The audience for All Fours may also find literary associations in the piece, whether Morris himself intended them or not. Eerily and wonderfully two of the black men function as clones, but not quite. The pair made me think of Tweedledum and Tweedledee in Alice’s Wonderland as well as Dupont and Dupond (pronounced the same way in French, in English translation called Thomson and Thompson), the hapless detectives in the Tintin comics.

Typically Morris accumulates a series of gestures–some of them suggesting an attitude or an emotion, some perhaps arbitrary–and repeats them in deftly varied ways throughout a tightly structured dance. In All Fours it’s thrashing arms, a hand cupped to the ear, fists with a single finger raised straight up, a woman standing on the thighs of a man who obligingly bends his knees to create her perch. You notice the ways in which Morris deploys this material and you think, Here’s a guy who knows what he’s doing.

My only problem with the Fall for Dance performance of All Fours is that the cast didn’t seem to be working with the lusty commitment Morris fans have come to count on. Why I can’t imagine.

The most fun and the greatest surprise of the evening was Lil Buck’s The Swan, a solo, partially improvised, set to the Saint-Saëns music to which Michel Fokine choreographed for Anna Pavlova. Lil Buck (aka Charles Riley) wasn’t wearing pointe shoes, though his limber gyrations in sneakers often whisked him onto pointe and demi-pointe. What he does is a form of urban street dancing called Memphis Jookin’ and he’s a born star.

Articulate Ankles: Lil Buck, both dancer and choreographer for The Swan

Photo: Erin Baiano

Accompanied by an onstage cellist (Joshua Roman) and a harpist (Riza Hequibal Printup) who, beautifully lighted, suggest a corner of Heaven, Buck (the “Lil” seems to be an honorific in his trade) makes a calm entrance. Then, energy coursing through him, he delivers arm gestures that suggest, simultaneously, both the rippling wings of a swan (at least as imagined by Fokine, and Ivanov before him) and the water that is the bird’s element. His whole body is preternaturally fluid. He has the most articulate ankles imaginable and the mobility of a contortionist in every joint. Buck’s Swan meets its death as the dancer slowly ties his body into a knot from which there is no escape.

There’s more to Buck’s performance than a lithe body, physical eccentricity abetted by grace, and a charismatic stage presence. He seems to identify with the swan in its plight, giving the creature the same kind of dignity and pathos that I once saw Galina Ulanova achieve in the Fokine version.

Right after the performance I went to YouTube, that gallery of innumerable uncurated images, to see and learn more. I saw that while the vocabulary of Memphis Jookin’ is small, the joyous defiance with which its inadequately privileged practitioners break the rules of Establishment Dancin’ is immense.

The most sublime contribution to the program was Trisha Brown’s Rogues, new work, set to music by Alvin Curran, that looks like part of something larger, still to be created. As it stands, it’s an exquisite duet performed by Neal Beasley and Lee Serle, one a head taller than the other. In gray jerseys and skinny jeans–typical Brown workaday garb–they do much of their dancing in unison or at least in canon. This tactic, of course, reveals the differences between things that might be carelessly considered the same.

As the dance progresses, Brown subtly and slyly persuades you not only to notice the differences between the two men but also to rejoice in them. Just to begin with, the shorter fellow is stockier, the taller one lankier, and these disparate builds affect the way they move and the very texture of their movement, even when they’re synchronized.

The men performed very faithfully in Brown’s style–fluid yet full of unexpected angles, understated and unaffected, yet with unwavering focus. They did remarkably well, as far as anyone can replicate a uniquely personal style. As yet, no one has fully succeeded. Onstage Brown was a marvel, tossing off sneakily complex moves as if she were sauntering down the road and performing feats of concentration as if she were part of a desultory conversation. Her remarkable physical sensitivity, her intellectual acuity, and her wry sense of humor make imitators look lazy. The “next” Trisha Brown would have to be an original, just as she herself is.

The Joffrey Ballet, which way back when was resident at City Center, flew in from its Chicago home to represent classical dancing. To me, Edwaard Liang’s Woven Dreams, set to music by Maurice Ravel, Michael Galasso, Benjamin Britten, and Henryk Gorecki, seemed essentially unwatchable. Svelte muscular bodies in sleek costumes rendered a slew of balletic conventions that lacked a coherent structure and afforded no clues as to musical inflection and emotional subtext. The dancers–hardworking if still needing a jot more technical polish–seemed to be, literally, just going through the motions.

The piece begins with a group emerging from an enormous, heavy web (designed by Jeff Bauer, who also provided the ice blue Vegas-goes-minimalist costumes). Oh so predictably, the web rises to serve as a ceiling and, many moons later, descends to hover over the performers’ heads, signaling the end of the ballet’s meaningless maneuvers.

Many of us in New York miss the Joffrey but Woven Dreams made me recall how many indifferent-to-godawful ballets the company has always had in its repertory. When Robert Joffrey was alive (he died in 1988), he fostered a rep in which easy-looking ballets, mostly by the facile Gerald Arpino, were programmed side by side with neglected but fascinating one-acters of the past by the likes of Kurt Jooss and Léonide Massine as well as more current masters like Ashton and Balanchine. At the same time, Joffrey commissioned work from gifted choreographers on the cutting edge, notably Twyla Tharp and Laura Dean. He remains a hard man to replace.

I should say here that a slot on a Fall for Dance program doesn’t let you fairly size up a company. It was never meant to. Fall for Dance offers pleasure and stimulation. Intrigued viewers must take it from there on their own.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

This is a terrific piece. I especially love what you write about Lil Buck’s “Swan.” Particularly evocative: “There’s more to Buck’s performance than a lithe body, physical eccentricity abetted by grace, and a charismatic stage presence. He seems to identify with the swan in its plight, giving the creature the same kind of dignity and pathos that I once saw Galina Ulanova achieve in the Fokine version.” I absolutely agree, and only wish I could express it this well. I was also interested to read what you learned from watching more Jookin’ on YouTube. Your research inspired me to do a bit of my own.

This sentence about Trisha Brown’s dancing is splendid as well: “Onstage Brown was a marvel, tossing off sneakily complex moves as if she were sauntering down the road and performing feats of concentration as if she were part of a desultory conversation.”

READERS: PLEASE SEE NICOLE COLLINS’ COMMENT, BELOW

Amen Sister Nicole! I love the YouTube film of Lil Buck and Yo Yo Ma, especially since it gave me some clues (many clues) to what this form, Memphis Jookin’, looks like in general. It reminded me of Maya Plisetskaya dancing Fokine’s “Dying Swan,” as it’s popularly known, in a Portland sports arena nearly fifty years ago, managing to execute those rippling arms when she was clearly spitting mad at the venue! There is more than one way to skin a dying swan . . .