School of American Ballet: 2011 Workshop Performances / Peter Jay Sharp Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 4 and 7, 2011

As classical dance fans know, the annual Workshop Performances of the School of American Ballet–New York City Ballet’s renowned academy–display the accomplishments of its budding teen-age dancers, some of whom will be the next decade’s stars, others who will make a corps de ballet ever more deserving of its name–“the body of the ballet.”

This year’s performances–I saw two of the three showings, the matinee and evening performances on June 4–can be considered a landmark event. The two casts of nine men (average age 17 ½) alternating in Peter Martins’s 1987 Les Gentilhommes proved irrefutably that, after decades of working toward the social acceptance of boys who choose to dance, America, with SAB in the lead, can produce a male contingent of classical dancers of the highest caliber.

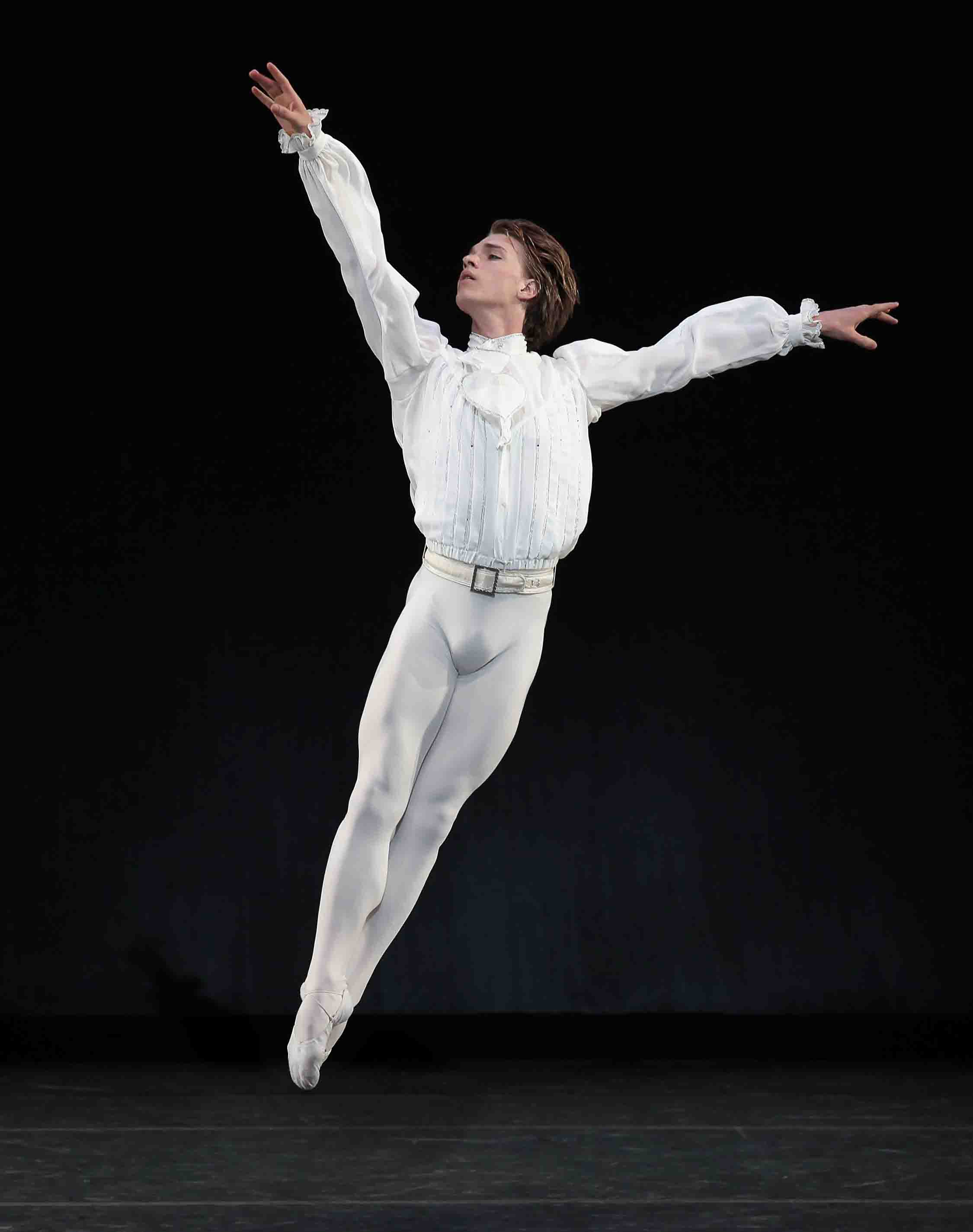

Amazing Grace: School of American Ballet’s Harrison Ball in Peter Martins’s Les Gentilhommes

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Set to felicitous music by Handel, Les Gentilhommes demonstrates the refinement a young man can achieve through rigorous schooling in strength, exactitude, selflessness, and unforced grace of manner. The ballet’s cast of nine is dressed in loosely pleated white shirts, ruffle-trimmed at the wrist and neck, and unforgiving white tights. They might have stepped out of Castiglioni’s Book of the Courtier, which describes the attributes a young man of the Renaissance needed to cultivate in order to shine in courtly society.

The breathtaking adagio in place with which the ballet opens consists solely of changes in posture and gesture, so the viewer can see the harmony of each dancer’s form from shifting points, as if she or he were slowly walking around a piece of sculpture.

Then one of the nine, placed at the center of the group, acts as its leader, proposing a brief sequence of steps that is then reiterated by the others–in flawless unison. This consonance is never mechanical or show-offy (like the sensational Rockettes’). Rather, buoyed by music and breath, it looks perfectly–albeit ideally–human.

The piece progresses with three sequential trios, each emphasizing a specific aspect of classical-ballet virtuosity. Finally the nine dancers assemble again, now in a diagonal line, and take up their call-and-response activity, first in brisk tempo, then quieting into the legato pace of the opening. Gradually the stage darkens and they perform a révérence (the traditional formal bow of ballet students to their classroom teacher, with which they will eventually recognize and thank their audience).

The deference of the bows and the falling darkness seem to be reminders that a dancer’s job is to serve his demanding art with humility, discipline, and devotion. Such a commitment eats up his youth and, because the body falters long before the desire to dance is quenched, lasts only halfway through his maturity. The reward is satisfaction in doing what one was destined to do–and, just possibly, glory.

Ad Astra Per Aspera: Young men from SAB–Joseph Gordon, center–in Martins’s Les Gentilhommes

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Seeing Gentilhommes again at the evening performance, I noticed many lovely details:

● Proof that the angle of the wrist and the placement of the fingers can matter tremendously. (Once you learn this from dancing, you can look for it beyond dancing. In sculpture, in acting, in everyday life.)

● A movement traveling down a diagonal side-by-side line-up of the dancers almost faster than you could see each one execute it.

● Grands battements in which the leg is not forced or hauled upward but flung high softly and easily, even buoyantly.

● Each man’s composed stillness when he’s finished a phrase and is “just” standing in place.

● The reaching into the air with a single arm, the eyes following and extending that reach, and then, only then, the body soaring straight upward, almost invisibly thrust off the ground by the legs and feet.

● The beauty of the beats, tiny and unemphatic, added to a jump without the least effort, simply to make the jump glitter. (It’s what the stars do to a nighttime sky.)

● Last, but most amazing, the men’s perfectly turned-out fifth position: feet locked tightly together, right heel to left toes, right toes to left heel, forming a base so secure, a rocket could be launched from it. Peter Boal, one of the most impeccable principal dancers City Ballet ever harbored, a member of the original cast of Gentilhommes, now artistic director of Pacific Northwest Ballet, confessed one day with rueful humor to the SAB boys he was teaching, “I feel as if I’ve spent my life getting in and out of fifth position.”

High Fidelity: SAB’s gentlemen in fifth position

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Albert Evans and Arch Higgins, both former dancers with City Ballet, did the superb staging. Their production looked as if Stanley Williams–Evans’s teacher, Higgins’s teacher, Boal’s teacher, Martins’s teacher–had coached it himself. At the premiere of Les Gentilhommes in 1987, Martins dedicated the ballet to Williams with the words Skol, Stanley!, as if raising a glass to the justly renowned (and loved) classical dance pedagogue, a man with a persistent vision of exquisite simplicity.

George Balanchine said that his Allegro Brillante, which opened this year’s Workshop program, “contains everything I knew about the classical ballet–in thirteen minutes.” And it’s an exigent 13 minutes for the leading couple–here Angelica Generosa partnered by Harrison Ball at the matinee and Joseph Gordon at the evening performance–as well as for the four necessarily highly accomplished couples who make up the ensemble. (At Workshop the ensemble was terrific and justly earned its own ovation.)

Co-stars: The ensemble of Balanchine’s Allegro Brillante

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Balanchine’s choreography to the single completed movement of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in E-flat major is exhilarating, often speed-driven and simultaneously insistent upon having its every image register with acute clarity. An abstract ballet, Allegro has no subtext whatsoever; it’s about the sheer thrill of the academic vocabulary–and Balanchine’s startling but eminently logical extensions of it–responding to the surging music.

As just one example, take the way the dancers’ arms and legs keep thrusting sharply into diagonal positions one way and another, then quickly reverse, often taking the whole body in a new direction. Again and again, the dancer looks like a weather vane in a lashing tempest. Then take another–perhaps the ballerina’s series of turns on pointe escalating into a string of every related turn in the book. Take yet another and you find your heartbeat has been accelerating all along the way.

Sparklers: Angelica Generosa and Joseph Gordon in Balanchine’s Allegro Brillante

Photo: Paul Kolnik

My one problem with all this is that I simply couldn’t take to Generosa, prodigy though she may be. Unlike most gifted pre-professionals, she’s already a finished product, secure in everything she does (and tops with a pretty smile). She looks as if she’s absorbed every bit of coaching she’s been given and does to perfection everything she’s been told to do. As a result, she has become an encyclopedia of scrupulously rendered feats. Now, if it’s not already too late, she needs to become a dancer.

Admittedly, the leading woman of this ballet has got to be a virtuosa–the role was created for Maria Tallchief–but a 17-year-old virtuosa who doesn’t seem to realize that there’s a world beyond physical prowess kind of dampens your day.

The piece was staged by Suki Schorer, formerly a principal dancer with City Ballet, an instructor at SAB for four decades, and a longtime provider of distinguished Balanchine productions for Workshop. She must have realized that, given the senior SAB students at her disposal this season, Allegro couldn’t have been staged effectively without Generosa, who danced all three performances.

Girl Crazy: Peter Walker, escorting Lindsay Turkel, one of his three dates, in Balanchine’s Who Cares?

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Balanchine’s Who Cares?, set to an irresistible slew of Gershwin songs, encourages belief in the choreographer’s assertion that “ballet is woman.” Susan Pilarre–like Schorer, an expert stager of Balanchine’s ballets–mounted the piece for Workshop with remarkable insight, but it was clear that she didn’t have enough women to fill the ballet’s requirements–or her own. Each of the female soloists, at the very least, must have excellent technique and, most significant, her unique “perfume”–if the ballet is to evoke the many moods of romance proposed by the songs and the choreography. Each should have the power to make you fall in love with love. But as past Workshops have demonstrated, there are vintage years in dancers as well as in wines, and this year’s crop had few women of that special quality.

Man About Town: Walker in Who Cares?

Photo: Paul Kolnik

It was left to the leading man to carry the show. He has a duet with each of the three main women, followed by a solo of his own. Peter Walker was fast and fleet in the role, always attentive to the lady in his arms–indeed he had no eyes for anyone but the one of the three he was dancing with at the moment. (This alone was bound to make viewers a little suspicious. Had Walker decided he was playing a trickster?) He went on to perform his solo with the casual ease of Jacques d’Amboise, who originated the part, but added to that a hint of cunning and danger. It suited the portrait of a young man about town who seems sweet and sincere enough but perhaps is not quite the gentleman he’s billed as being–or that Walker had appeared to be, not an hour before, in Les Gentilhommes.

A male quintet, to Bidin’ My Time, offered viewers another look at performers who’d caught their eye earlier in the program. I was particularly happy to see Austin Bachman, whose promise and progress I’ve followed for a couple of years. He still looks boyish and is more than ever a model of classical correctness–presented softly, as are his modesty and charm.

I was delighted, too, to notice Silas Farley–tall, willowy, and gentle–for the first time. He’s the sort of dancer who makes you imagine the ballets that might suit him, even though, so far, you’ve only seen him in one or two.

Follow the Leader: Jock Soto as the Ringmaster parading 48 girls from SAB in Jerome Robbins’s Circus Polka

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The school’s Children’s Division, represented by Circus Polka, looked better than ever this year. Every time I see this three-minute showpiece, devised in 1972 by Jerome Robbins for 48 girls–ranging from tiny enough to be (wrongly) dismissed as “cute” to just pubescent middle schoolers–the pony tails are longer and bouncier; the uniformly slender legs, molded by ballet training, more lithe and disciplined; the footwork more finely articulated; the stage presence more confident and joyous.

There’s an anecdote attached to the piece that’s recalled whenever the ballet is performed. Back in 1941 the Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey Circus invited Balanchine to choreograph a routine for some 50 elephants and the pretty girls who rode them. Accepting the challenge, Balanchine asked Stravinsky (who, along with Tchaikovsky, was a source of unending inspiration for him) to compose a brief score–a polka perhaps–for the occasion. After being assured that the elephants were “very young,” the composer complied and, in 1942, the show went on. The score bore this dedication: “For a Young Elephant.” Three decades later, for City Ballet’s Stravinsky Festival, Robbins co-opted the music for three tiers of SAB girls and an adult Ringmaster who put them through their paces.

Spelling Bee: For the curtain line of Robbins’s Circus Polka, the young dancers form the initials of Igor Stravinsky, who composed the ballet’s score

Photo: Paul Kolnik

This year’s Ringmaster was Jock Soto, a former City Ballet principal dancer, now a member of SAB’s faculty. The piece was staged by Garielle Whittle, a longtime member of the faculty as well as children’s ballet master for the company. The Ringmaster wields a mean whip (which of course never touches a child). Unarmed, Whittle prepares youngsters to combine exorbitant energy and technical precision with springtime freshness and grace.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

I enjoyed this review and the accompanying Paul Kolnik photographs so very much – you made me feel as though I were sitting in the audience. Thanks!

I was there on Tuesday — much the same effect, with only slightly different casts. Couldn’t agree more with your take on Generosa. I found her dull and unmusical, but I found almost all the girls a little disappointing. Ball and Walker seemed to be the people to watch. No one coming up seems to have the exuberance of Damian Woetzel, although Andrew Veyette may get there, but I was much encouraged by the boys, in general.