New York City Ballet: George Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream / David H. Koch Theater, NYC / June 16 -21, 2009

George Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, screening of the 1967 film / Baryshnikov Arts Center, NYC / May 26, 2009

George Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, created for the New York City Ballet in 1962–with co-collaborators William Shakespeare (libretto) and Felix Mendelssohn (music)–is a perennial enchantment.

Some observers will dismiss it as too “pink” (a favorite Barbara Karinska color for her costumes), but it covers a wide spectrum of jealousy, greed, questionable uses of power, sexual attraction between woman and ass, foolishness, stupidity, and murderous rage (albeit most of these tempered by their comic aspect) before arriving at its magically happy resolution.

You know the story; you read it at school. If you’ve forgotten it, treat yourself to a refresher course. The delightful text is no further away than your computer (http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/8609). Though Balanchine is remembered as saying he was primarily inspired by the music, he renders the narrative deftly. At the age of eight, apparently, he played one of the tiny creatures of the air that inhabit the story in a St. Petersburg production, and City Ballet alum claim he remembered and would recite excerpts from the text in Russian.

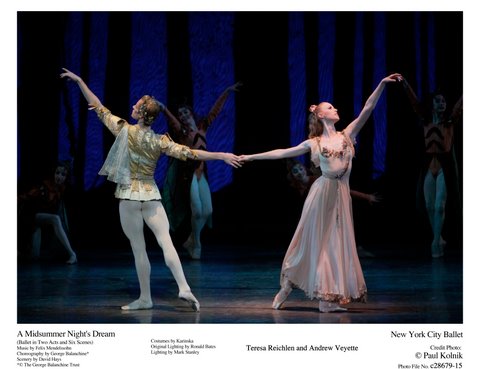

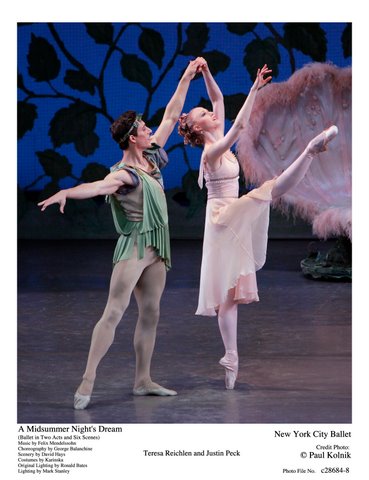

From the company’s week of Midsummer performances this season, at the David H. Koch Theater, I chose the cast that featured Teresa Reichlen as Titania, Queen of the Fairies. Reichlen’s career is still relatively young, but she’s been a winner from the start. It’s not just the impeccable dancing accentuating her very long limbs and perfect line I admire, but her courage as well. She tackles prominent assignments with authority and, it seems, the expectation of pleasure.

As Titania she has decided upon a combination of empathy with her fellow characters–child, adult, and–yes–donkey. She is alert to their needs without ever relinquishing the characteristics of queenliness. For example, she allows the laborer magically transmuted into an ass his yen for dewy grass to nibble on but never loses her faith that–coaxed onto his hind legs–he may make a suitably elegant partner in a pas de deux.

When, after much imperious argument, she finally cedes possession of the changeling child in her retinue to Oberon, her kingly counterpart, it’s simply because he desires it so intensely (even though his methods of acquiring it include attempted kidnapping). Everything about Reichlen’s Titania is warm as well as aristocratic.

Reichlen can’t yet lay claim to the sudden plunges from the vertical that made Suzanne Farrell’s celebrated interpretation so sensuous and exciting, but perhaps that is never to be.

The male stars in this performance, Gonzalo Garcia as Oberon and Troy Schumacher as Puck, were adequate but not memorable. The most striking performance was given by Janie Taylor, beautifully partnered by Tyler Angle, as the couple in the wedding divertissement who embody perfect love. This season has marked Taylor’s return to the repertory after prolonged absences. A fragile, often thrillingly wild dancer, Taylor is one of those performers whose soul seems to dance through her. The audience recognized this in a instant, with hold-your-breath silence and then tempestuous applause. She’s one of a very rare breed and deserves all the cherishing that can be given her.

A bevy of children (pupils of the company-affiliated School of American Ballet), playing the chorus of winged insects or fairies threaded through the piece, made it heartening to see that today–compared to yesteryear when I first saw the ballet–the students have acquired a fleetness and clarity unknown to their predecessors and at an earlier age. (This means that younger, thus smaller, children can be used, offering a more piquant contrast with the adults). Balanchine, of course, had a way with dancing children that has never been equaled in the States. He assigned each level of youngsters steps they could do effectively, with precision and verve, without losing their natural charm.

Transparency note, should one be needed: As a student at the School of American Ballet, my daughter danced for a few seasons in this chorus of airy sprites. She was young enough to need an adult escort to and from the theater, and it was a long, dreary wait between commutes, since the kids figure in the choreography from beginning to end. But the music was piped into the chaperones’ holding pen during the performance, and I’d often find my way (i.e., sneak into) the back of the auditorium just in time to watch the exquisite Act II pas de deux. Danced, appropriately, by a couple that has no role in the story, it is an abstraction of love’s deepest feelings and perfectly beautiful.

Suzanne Farrell as Titania

Courtesy NYCB Archives

A few weeks before the City Ballet finished its spring season with seven performances of Midsummer, the Baryshnikov Arts Center offered a single screening of the 1967 film version of the ballet, directed by Dan Eriksen and the choreographer. Whatever its flaws, and they are considerable, it reveals the qualities that made its leading dancers legendary. The young Suzanne Farrell reveals miracles of supple and impetuous motion as Titania. As Oberon, Edward Villella deploys his mercurial footwork, mating ferocious speed with rock-steady power. He originated the role, and his only subsequent rival since has been Helgi Tomasson, rendering the choreography in the fleet style that made him look airborne. Arthur Mitchell, as Puck (he, too, created his role) is simply not replaceable–a gleaming-skinned figure with a handsome, knowing face, who is clearly a born trickster.

The cast also includes the already dazzling Patricia McBride, Nicholas Magallanes, a soulful Mimi Paul, Jacques d’Amboise, and Allegra Kent. Veteran City Ballet followers will also enjoy singling out, amid the corps, dancers they recall fondly from the company’s mid-twentieth-century blossoming.

In many ways the production is a natural result of the era’s prevailing film conventions, which were then so commonplace as to be unnoticeable. But in no way is it equal to the live performances the City Ballet has given us over the years and what video has accomplished in the last half century to transfer ballet more authentically to the screen.

The worst aspect of the film is its scenery. It’s not merely a case of the patently fake asking us to take it for reality but also a question of its hampering the choreography. The combination undermines the ballet in both its woodland-animated-by-spirits and its aristocratic locales. In the forest, the landscape has the falsity of a plaster and plastic background for a model railroad or a Playmobil rainforest. What’s more, the pseudo-Mother Nature foliage constantly obscures the view and threatens the dancers with vines to trip over, trees and bushes to block their path. One of the basic requirements of Balanchine dancing is clear space.

The second act takes us to Theseus’s court to celebrate three weddings, those of the Duke of Athens himself with the Amazon huntress Hippolyta (an odd couple, perhaps) and the two pairs of plebeian lovers, whose complicated, shifting interrelationships (“What fools these mortals be!”) are finally straightened out–not without some early errors–by Puck at Oberon’s command, using doses of a rare rose pollen. The royal residence and grounds, with their imposing staircase and multi-tiered fountain, look like a Reno rendition of Louis XIV’s palatial concept of house and garden.

At the finale, back in the forest, Titania and Oberon are reconciled; she relinquishes the changeling child in her retinue that Oberon coveted to the point of their quarreling vehemently over it. But they are, pointedly, not included in the marriage rites (perhaps, as king and queen of the fairies they are already “married,”) and they part, moving off in opposite directions, though slightly turned to each other, each gently waving a hand in an amicable temporary farewell. Balanchine liked to explain (perhaps tongue in cheek) that they’re fairy folk, a breed that doesn’t engage in carnal intimacies.

Inevitably, the film makes alterations to the choreography that are disconcerting, at times downright confusing when it comes to keeping the plot straight, especially concerning the quartet of middleclass lovers. At other times, there are effects that are plain silly, such as the “magical” appearances of characters out of thin air.

Balanchine makes magic with his imagination that is far more potent than elementary camera tricks.

The camera does its worthiest work with close-ups. While the ravishing dewy beauty of the sleeping Titania is pure Hollywood, where Balanchine did some time in the 1930s and ’40s, it’s a blessing because you’d never be close enough to see it in the theater.

Now for the really bad news. Just before attending the single public showing of the film at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, I viewed it on my computer, using a screener provided by the celebrated Parisian archival institution, the Cinémathèque Française. It was wonderfully clear. The mechanics of the BAC showing, also using a Cinémathèque print, were simply not of professional caliber. Throughout, the image was migraine-inducing–severely blurred, accompanied by deafening sound. Nobody tried to fix this. Then, at the brief live Q & A that followed the film, the microphones worked only sporadically–an apt coda to the general malfunctioning of the event. Suzanne Farrell, straightforward and charming, and the deft interlocutor, the dance writer Robert Greskovic, coped with the situation like troupers.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias

Lovely column.

One question: did you see Melissa Hayden’s Titania? (She did the premiere in 1962.) Did she also plunge from the vertical, as Suzanne Farrell did: that is, is the plunge part of the choreography or specific to Farrell?

Tobi, have you seen Pacific Northwest Ballet’s version of “AMND,” which was filmed by the BBC at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in 1999? I’d be interested in your comparisons between the two film versions!

Unfortunately, I haven’t seen that version. Thank you, on my part and that of SEEING THINGS’ readers, for calling it to our attention. t

PLS. SEE MINDY ALOFF COMMENT, BELOW.

If I did see Melissa Hayden as Titania, I don’t remember it. I recall Suzanne Farrell’s performances in the role vividly. Of all the wonderful ballerinas I remember in the role, I think Farrell was most eccentric and beautiful in her play with gravity. I also believe that ballets change with subsequent casts, so that those “plunges” which may have entered “Midsummer” through Farrell’s proclivities (and Balanchine’s urging her on) have, for the veteran viewer, become part of the choreography, Thank you for writing. Perhaps other readers will have interesting responses to your question. t

Dear Tobi,

Great to “read” your voice again. I too was at the screening of Balanchine’s “Midsummer.” I agree it was a bit dated but one must remember when the piece was filmed. Imagine what it would look like now with updated special effects.

I was amazed by how beautiful Allegra Kent was in the Divertissement and can’t tell you how excited I am to see Suzanne Farrell recreate it for the Kennedy Center season of her company in the Spring.

Holly Hynes

Costume Designer

Costume Consultant George Balanchine Trust

I have not seen the film of Pacific Northwest Ballet’s production of “Midsummer,” but I saw five performances of the ballet when it premiered in Seattle in 1997. Francia Russell and Kent Stowell received permission from the Balanchine Trust to mount a new production with sets and costumes by Martin Pakledinaz; Balanchine’s choreography, needless to say, remained the same. I know that Russell found the second act set of the original cumbersome for dancers and I’m wondering too if they had seen the 1967 film. Russell, who has been staging Balanchine ballets all over the world for several decades, handpicked by Balanchine when she was in her twenties, did not tamper with his choreography for this version of the ballet. She did, however, add an apotheosis with lighting effects that were not part of the original production; it worked well, as I recall. It would be interesting, I think, to look at the 1967 film and the later one of PNB, indeed made in London when the company was on tour, consecutively it seems to me. Meanwhile I am grateful to Ms. Tobias for putting me in the theater with her at City Ballet’s recent performances.

Balanchine’s “Midsummer” ballet has been one of my favorites for decades. I think that this is one of his true masterpieces. Not only is it riveting musically but the characterization of the adult roles, down to the tiniest fairy, is so distinctly indigenous to the choreography itself.

Each role is in its own realm and reality, and comes to life in magical juxtaposition of the others. I can hear the Shakespeare and I can feel the palette of feelings in a different way than when viewing the play.

Perhaps it was the moment Bottom ate the grass, upon my first viewing of the ballet that was a “eureka” moment for me as a budding choreographer: that simple truthfulness of character– suit the word to the action and the action to the word.

As a choreographer for dance and theater and as the artistic director of my own company, I have always been inspired by this ballet, and often in the gloom of January I am looking forward to June in which I might yet schedule another viewing of this magnificent work.