The dress on my back, the cloth on my dining table–unique, beautiful, old, and absurdly cheap. “Where’dja get it?” the appreciative and envious exclaimed. Gerry’s, of course.

I came across Gerry and his goods plowing my way home through a street fair devoted, as these events are nowadays, to the peddling of tube socks, junky electronic gizmos, bras and bikinis ostensibly name-branded, off-brand sheets, discontinued makeup and food as likely to kill as to nourish you.

It was high summer and the weather was stupefyingly hot and humid; the wares, depressingly tacky. Suddenly I spied, manifesting itself like an oasis-in the-desert mirage, a long rickety table heaped with fabric that all but spelled out “vintage” in neon light. I spent the next three hours there, pawing through the mound, finding things, among a crowd of enthusiasts. From them I learned that the scruffy youngish man in charge was called Gerry and that he and his offerings appeared irregularly–this was part of the mystique–at such fairs.

Every Sunday morning in the next month, I went out hunting for the elusive Gerry’s “show” (as I found he called it), sometimes successfully, sometimes not. Eventually, I got on a semi-secret phone-alert list that made me privy to the dates and venues of upcoming shows, relayed by a disembodied young female voice. From then on, on the next designated date, fifteen minutes before the appointed hour, I would join the faithful gathered at the indicated Upper West Side locale, waiting in a state of anticipation comparable to that of a very young child on the morning of his birthday. I was rarely disappointed.

Here’s how the maverick operation worked: From the back of a roomy SUV, Gerry, the sole proprietor and impresario of the enterprise, drew a large collapsed trestle table and set it up in the street. Then, with the help of a few volunteers from the eager crowd, he removed dozens of giant trash-bagged bundles from his vehicle and piled them high on the table. They formed a veritable mountain that loomed high over the heads of the participants. Only after the last bag had been stacked did Gerry give the signal that his low-end boutique was open for business. We, his clients, then precipitously threw ourselves upon the bags, ripped them open, and began rooting through the loot.

Just before the opening gun, Gerry had thrust at each prospective shopper a large plastic bag of an institutional royal-blue hue. A horizontal oval cut out near the top of the bag created a handhold. In these circumstances, however, you grabbed your bag, slung it over your arm, and pushed it way up to the elbow so you’d have both hands free. Digging for treasure chez Gerry was definitely a two-handed job.

What, exactly, was in the mountain? Delicate christening gowns, an amazing number of them. Spunky daytime dresses that women wore before jeans were declared to be the uniform for ordinary life. Cocktail dresses, ball gowns, and tuxedo jackets (which today’s women know look fabulous over their uniform of white t-shirt and faded Levis). Tablecloths galore, sometimes with matching napkins, in every size imaginable–from bridge-table squares to banquet-length double damask. Towels of every ilk, including those divine European linen ones with the owner’s initials embroidered at a corner in red cross-stitching. Yesteryear’s baby clothes and kidwear, a study of which would make a fertile dissertation subject for a budding sociologist. Undergarments that included pantalettes from the Victorian era and peach-colored corsets your grandmother might have worn (both find rakish uses today). Hats, shoes, and gloves (occasionally the white kid “Opera length” kind that reaches from impossibly slender fingers to above the elbow). Shards of ravishing embroidery, beading, or lace–all sheared from their original location but considered by some unknown salvager–bless her or him!–too wonderful to jettison.

The basic endowments for your initial search through this merchandise were a keen eye, speed, and ferocity of purpose. The idea was to stow away in your increasingly heavy blue bag anything at all that spoke to your imagination. The elimination process would come later.

Everything was “used,” of course. And nearly all of it was old, some of it, as I’ve indicated, seriously old. Rips, frayed edges, not quite obliterated coffee or wine stains, and other signs of age often made the garment–or linen item–somehow more precious, the way wrinkles give a mature face character. Occasionally I bought examples of meticulous mending, an art that has vanished in today’s throwaway culture. The love, labor, and deftness with which a hole in an antique linen sheet had been repaired never failed to pierce my heart.

In the world of Gerry’s, age was a plus. His customers seemed to agree that clothes were better “back then,” whether they thought “then” was the Sixties and Seventies or the Thirties and Forties. (I admit to the insufferable snobbery of believing that fashion–in a classical sense that includes wearabililty and grace–ended in the Forties.) Clothes were certainly better made back in the day.

Among my favorite acquisitions were black and midnight-blue dresses from the Twenties through the Forties that became mainstays of my “look,” and then, skipping ahead to the extravagances of the Seventies, a killer-flamenco dress–several pounds of flirtatiously ruffled black lace that I never wore but took out to revel in at least twice a year. My oddest find from the stylish past? Two pairs of men’s white suede summer oxfords with those characteristic perforations–very Great Gatsby. They were almost brand new, and they actually fit.

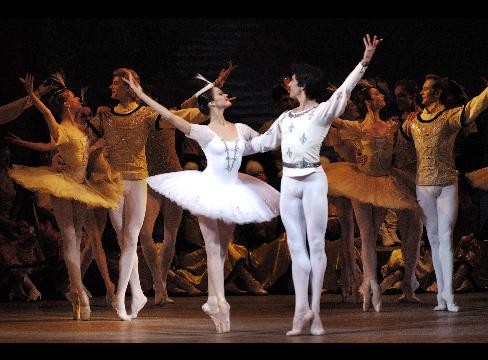

A small percentage of Gerry’s offerings were actually theatrical costumes. Another small percentage–one I cherished–comprised extremely old items. A wisp of a white finely embroidered handkerchief, at least two centuries old, from the look of it–you could, as they say, read a love letter through it and time had lent it a faint sepia cast–had managed not to give up the ghost in the ravages we perpetrated on the dense, twisted pileup of cloth. I rescued it, washed and ironed it with scrupulous care, and took it to Renée, my dear friend in Paris. Utterly in sympathy with it, she had it framed and hung it in her bedroom, in the company of leather-bound books equally antique.

Where on earth did Gerry get his stuff? Of course we were curious, but in vain. He was cagily vague on this subject, even if questioned directly. “Oh, here and there.” Costume-museum cast-offs was one of the most shocking and unlikely sources he’d mention when pressed further, though the nature of his more compelling holdings hinted that he was telling the truth.

Gerry’s clientele was largely female and divided between two subsets: those who dressed with debonair éclat, looking to add to their holdings, and those–collagists and quilters among them–who converted their acquisitions radically, giving them a completely new identity.

Regular Gerry’s customers got to know each other and, while frenetically mining the fabric mountain for items that would suit them, always took the time to find things for their sisters. “Who’s into lace?” one might call from one side of the heap, holding high a gossamer white cloud, then pitching it across the towering stack toward the ebullient voice that replied. Or, “Mirelle,” uttered in a shriek of pleasure, “you’re gonna love this!” and the said Mirelle’s arm would shoot up–palm cupped, fingers splayed–to catch the soft missile being flung in her direction.

The only motionless figure I ever saw in this crowd was Sienna, a ravishing child about seven years old, with red-gold hair falling to her shoulder blades and curling in pre-Raphaelite tendrils around her pale face. She was exquisitely poised and unusually silent. By contrast, Estella, the middle-aged grandmother in charge of her, was an earthy, loquacious type with gypsy looks. Physically and temperamentally, they seemed entirely unrelated. I guessed that Estella was buying for a modest private resale enterprise, perhaps to put bread into the child’s mouth.

At one Gerry’s session, I insisted upon buying Sienna a winter coat that the gods had obviously designed, a half-century back, with just this eerily lovely child in mind. Executed in black poodle-fur, with a neat little collar and a double row of buttons parading primly down the front, it was cut to hug a slender torso, then flare out at skirt level as if whipped suddenly by a November gust. Perfect in its propriety, imaginative in its fabric, meticulous in its tailoring, it was fit for the heroine of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess in her days of good fortune.

To return to the Gerry’s ritual: Once you felt you had fully inspected the hoard of stock (this took at least an hour and a half), the next step in the selection process was to dump the contents of your blue bag out onto the adjacent sidewalk and inspect it, piece by piece, to see which items you really must have or die.

While you did this, another client might hover nearby, politely if sometimes pointedly waiting until you, the original claimant, were done considering a good percentage of your items. The observer wouldn’t touch a thing until the moment seemed right to inquire, “Can I look at your discards?”

A cooperative client (and most were) would then sort her haul into three distinct piles that she indicated were, as far as her own taste and needs went, Keeper, Maybe, and Forget It. The waiting observer was entitled to examine–and stash in her own blue bag–anything in the Forget It pile. By an unspoken courtesy, she would shoulder the responsibility of returning the items she didn’t want back onto the still-looming mountain on the trestle table–unless yet another hopeful connoisseur of discards stood waiting (body motionless, avid eyes scanning) behind her.

Of course these rules, which evolved logically from the needs of the situation, were written nowhere and spoken about only when a newcomer to the process, at a loss as to how the system worked, asked for initiation. The conduct of the whole affair was a convincing argument for letting women run a nation’s government.

Decisions about household linen–whether for table, bed, or bath–can be made by eye and feel alone. Sheer guesswork prevails in choosing articles of clothing you plan to present to your near and dear. But garments you may allow to enter your own wardrobe must be tried on, though an intuitive few can look at a lavish night-life costume or a sober pencil-slim skirt and know if it will fit them flatteringly. Most of Gerry’s clients needed to try on the clothes that had snagged their attention and so created dressing rooms of an invisible architecture on the sidewalk, close to the building line, as if having a bricks-and-mortar structure only inches away from your all but naked body somehow preserved your modesty.

A typical Gerry’s customer, you see, would arrive at the scene clad in the usual flea market costume–jeans or shorts that had seen far better times, a ratty t-shirt, and a banana pouch to hold the bare necessities (money–needless to say, Gerry accepted only cash; a bank card for getting more money; a Metro card; a piece of i.d.; a comb). The savviest among us learned to skip regulation underwear–bra and bikini pants, an outfit the New York police consider adequate for the beach but insufficient coverage smack in the middle of town–and substitute some sort of cat-suit arrangement cut back to biker-shorts height on the legs and singlet sleevelessness on top.

No mirrors were available, not even the usual flea market looking-glass, shakily angled against an unreliable support, so cheap it reflected you with fun-house distortion. With luck, shop windows, if a shop’s interior was dark enough, would provide a murky likeness.

Other than that, we used our own finely honed instincts about how a garment felt on our body and our sister shoppers’ opinions. “What do you think?” we’d ask, presenting ourselves dead-on to the friend we had brought to the scene or an acquaintance we had made on the spot, then revolving in slow motion to be inspected from various perspectives.

Nearly always, the negative responses combined truth with tact. The positive ones, in their enthusiasm, were less decorous. “It’s totally you. You’d be insane not to take it.” Or, “If you don’t take it, I will–and cut it up into a dozen pieces and make pillows.” The dismantling threat often convinced the doubtful model of the garment that it was her moral duty to extend its life intact. Pillows could come later, after she had worn it to death in its original form.

Once a client had winnowed her holdings to the pieces she really wanted, she stuffed them back into her blue bag, deposited any further discards that hadn’t been gobbled up back on the heap, and placed herself at the end of a line of people that led up to Gerry.

The line could be long, but the pricing system had the swift efficiency of a guillotine. One by one, you’d remove the items from your bag and Gerry would tersely quote a price. “Three bucks.” “One.” “Five.” “Ten.” On each item, the shopper was allowed only one of two responses–yes or no. Haggling was forbidden. If you answered yes, Gerry scribbled the number down in a notebook that had seen much service. If your response was no, Gerry took the item and tossed it back on the heap. Once everything in your bag had been priced, Gerry added up the numbers in his notebook, announced the result, and you forked over that many dollars. The entire process clocked in at under three minutes.

You then scooped your yeses back into your blue plastic sack–or, if you were a Big Buyer, like Estella, into one of those ubiquitous plaid zippered shopping bags you’d presciently brought along–and moved on to the nearest Starbucks for a restorative dose of caffeine.

Needless to say, once the madness of the moment had subsided, some of our purchases would turn out to have been mistakes. But, as my frequent companion on these forays–Andrea the quiltmaker, author, swimmer, and Ph.D. candidate–points out, sighing with nostalgia, the entertainment value of The Gerry Experience was reward enough for the lavish investment of time and the ridiculously modest investment of cash.

Nostalgia? Yes, after several madcap years, Gerry’s enterprise folded. Not even his most persistent regulars could trace the man. Having created his unique delight for a time, he was gone–like Mary Poppins. Dozens of us fans were left broken-hearted–and with Sunday mornings once again at our disposal. Finally we might have time to clean our closets.

© 2008 Tobi Tobias