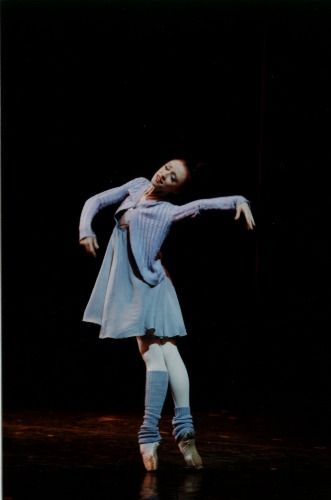

Kirov Ballet of the Maryinsky Theatre: Cinderella / Kennedy Center: Opera House, Washington, DC / January 11-16, 2005

At the behest of the Kirov Ballet, Alexei Ratmansky (now head of the Bolshoi Ballet, late of the Royal Danes) took Perrault’s seventeenth-century, definitive text of the fairy tale and Prokofiev’s haunting 1944 score and concocted a Cinderella for our cynical times. In this version of the ballet, it’s taken for granted that everyone in the story but the principal pair is as nasty and self-serving—or simply as weirdly off-putting—as possible. The production had its premiere in St. Petersburg in 2002 and in DC at the Kennedy Center in this relatively new year several days before I got to see it, so I can’t say I wasn’t warned by advance description.

Ratmansky hasn’t so much meddled with the basic story as given it a turn of the screw via his concept of the characters and their setting. Cinderella, infinitely sweet-tempered in trying circumstances and resilient in her endurance, is the least tampered with. If she dwells just a tad too long on embodying wonder in the face of dawning romantic love, who can blame her, her only alternative being housework? The girl’s stepmom is an over-the-top harridan with a certain witchy glamour, foisting not only her daughters on the eligible Prince but herself as well. The Dreadful Daughters (one skinny, one plump) are one-liner cartoons. Dad is a caricature of hapless alcoholism. (C’s dead mom makes a cameo appearance, evidence only of Ratmansky’s inability to tell a story effectively.)

The Prince, mercifully, is a darling. However, his travels to find the girl whom the shoe fits consist of his visiting, first, a female cat house, then its male equivalent (both instances culminating in his being ridiculed for shoe fetishism). Ratmansky misleads you to think the excursion’s an investigation of the fellow’s sexual identity rather than proof of his ardent fixation on the worthy object of his love. The Fairy Godmother is a street person with a balabusta temperament that is almost instantaneously wearing, and the quartet of male Seasons, whom she summons to watch over Cinderella, seem to be the alter-egos of the bathhouse crew.

When and where are these creatures holding forth? The ballet’s set, designed by Ilia Utkin and Yevgeny Monakhov, opts for a punitively stark urban world. The locale is defined by a black-on-white drop curtain that suggests an architectural cityscape and an all-purpose structure that furnishes the stage with a skeletal, staircase-rich scaffolding reminiscent of grim elevated subway stations. The ballroom is indicated by a line drawing in radically receding perspective. Overhanging the scene, a giant metallic hoop that looks like a crown of thorns flips from vertical to horizontal, serving as both curfew clock and postmodern chandelier. A flat representation of lavishly folded red curtain, hung upstage center when the scene represents Cinderella’s home, seems to be an ironic gesture in the direction of theatrical voluptuousness.

The costumes, by Elena Markovskay, run from rags to grudging riches. At home, Cinderella wears the picturesque schmates female ballet dancers affect for practice sessions. Her ball dress—all limply hanging tulle of the polyester persuasion gussied up with random glitter—can be described most charitably as being in the Soviet style of dress-up. The ball guests, representing take-no-prisoners chic, wear stripped-down formal dress (with rakish little black Deco period hats for the ladies). The Prince’s all-white evening clothes have been aptly compared by the Washington Post’s Sarah Kaufman to the Good-Humor Man’s uniform; I thought of Liberace (before he advanced to screaming-pink sequins). Suffice it to say that, excepting the clock-chandelier, there isn’t an iota of magic—or even generosity (the key to Cinderella’s temperament)—in the scenic investiture of this production.

As if this weren’t disappointing enough, the choreography is even more unequal to the occasion. It lacks amplitude—in every way. Main figures in the story are left onstage for long stretches with nothing to do but perch decoratively on the scaffolding or stand forlornly, fidgeting aimlessly, trying to look concerned. Significant action for large groups has been ignored. Program-length story ballets meant for opera houses require, among other things, an ample corps de ballet deployed in sweeping, reasonably complex patterns that make a big visual impact and offset the work of the principals and soloists. The guests at the Prince’s party—strolling about, alternating unconvincing disco moves with flimsy indications of traditional ballroom stuff—come nowhere close to fulfilling this mission.

The action for the unattractive characters—and for the good guy and girl as well, when they have nothing better to do—is dominated by angular distortions and grotesquely exaggerated mime. The dumb shows jar especially when they fail to include the props they cry out for (a scrubbing brush, for instance) or are utterly incomprehensible (what does a handful of wildly agitated fingers mean?). For comic turns, I think Ratmansky has tried to borrow from the music hall, vaudeville, and raunchy clowning—but he hasn’t got any gift for the low-down genres. The antics he devises for, say, Cinderella’s step-family, lack the subtle observation and timing of good clowning; devoid of depth and variety, they’re hardly funny at all.

Some of my colleagues have praised the passages of classical dancing for Cinderella and the Prince, alone and together, as consolation for the rest of the choreography, which is almost pathetically makeshift. Granted, the classical segments are prettier—and charged with appealing emotions like wistful yearning, nascent joy, and, ultimately, the abandoning of self to other. That said, Ratmansky’s classical mode relies on a scandalously limited vocabulary in the contemporary Russian style, showing off an almost self-congratulatory perfection of line, exaggerated liquidity of motion, circus-worthy flexibility, and the ability to spin like the proverbial top. It favors the eye-catching stuff while blithely ignoring smaller, more intricate pleasures, like petit allegro. Worse still, these passages lack a coherent structure. They consist of one gorgeous-looking move after another, performed in disjointed succession rather than in musical phrases. Unrelated to one another as these bits and pieces are, it’s impossible for them to add up to anything. Hierarchy, modulation, lucidity—keystones of classical dance—are noticeably absent here.

The single area in which Ratmansky succeeds in his Cinderella is the psychology of romantic love. His solos for his heroine and his duets for her and her prince are both inviting and persuasive. Cinderella’s feelings—as she is gradually introduced into a world that includes love—are given the leisure to shift and to register, in observant detail. The duets display not just the ecstasy of love triumphant but also the process of developing love and its necessary companion, trust—along with the pitfalls of momentarily failing self-confidence, missed connections, and even misunderstanding. If the happy ending of the ballet seems barely possible in the vile surround—not just of Cinderella’s dysfunctional family unit but in the ostensible aristocratic world as well—that Ratmansky creates with such relish, perhaps that snatched-from-hell miracle suits our corrupted times.

The two sets of principals I saw—Natalia Sologub with Igor Kolb and Irina Golub with Andrei Merkuriev—were marvelous within the limited range the choreography offered them. Sologub, rightly chosen for the first cast, made the more poignant of the Cinderellas. A lyrical dancer with an infinitely malleable body, she created a heroine modest and innocent in demeanor, tremulous in her anticipation of joy. She was all pathos, vulnerability, and tenderness, spiced with just the right amount of spunk. When, at the ballet’s close, she lay down in darkness with her beloved, sheltered only by a velvety night sky adorned with drifting clouds and glowing stars, she seemed to have found her proper domain—in the realm of kind hearts, not coronets. Irina Golub was more theatrically vivid in the role, more firmly planted in her technical prowess and in her determination to show it off, along with her considerable charms. If her interpretation seemed to me to lack the quality we call soul, it was because she’s less naturally suited to Cinderella’s wistful yearning and reticence, to that heroine’s embodiment of unalloyed goodness—and because I’d seen Sologub.

Both Kolb and Merkuriev, both of modest height but great talent, made wonderful, very different, Princes. Kolb’s dancing is strong, clear, pure to the point where it might provide textbook illustration, and yet informed with grace. He does a dutiful job of creating a character, but you can tell that his real raison d’être is to display the abstract beauty of classical dancing, step by step. Merkuriev is immensely appealing in looks and manner—the kind of guy a girl’s mother hoped she’d bring home back in the days when suitors had to earn parental approval. He’s warm, sweet, and boyish, impeccable yet easy in his behavior. Though he’s a fine technician, he keeps his dancing uniformly soft. All the edges are deliberately smudged, which gives his work the voluptuous quality of daring deeds half veiled by fog. All four of these dancers deserve more challenging material, and their already admiring followers deserve to see them in it.

Ratmansky’s mind seems to be a grab-bag of references, packed with things like Russian folk dance, to say nothing of all the ballets he has ever seen. My favorite throwback in his Cinderella is the resemblance—extending even to a couple of direct quotations—of the heroine and the Stepmother anti-heroine to the pure, deserving, gentle-tempered Hilda and Birthe, the hot-tempered, lascivious daughter of trolls, in Bournonville’s A Folk Tale.

A pair of useful questions to ask about any production of Cinderella: One, would you take a child to it? Two, would you take a grown-up to it? For me, Frederick Ashton’s ravishing version, created in 1948 for the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet and shown to just about universal delight in New York last summer as part of the Royal’s contribution to the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration, gets a pair of yeses; Ratmansky’s gets two noes. And yet, without any doubt, I’m curious to see Ratmansky’s next effort myself.

Photo: Natasha Razina: Natalia Sologub in the title role of Alexei Ratmansky’s Cinderella

© 2005 Tobi Tobias