I have written “Obsessed by Dress,” a meditation on fashion or–more broadly–clothes, and over two dozen books for children. You can find out more about these diversions from journalism by clicking on (what else?)

Archives for 2005

Shannon Hummel/Cora; Dancemopolitan

Hummel’s Elsewhere is enormously sophisticated on several levels, from the nuanced gradations of feeling expressed to stage pictures that remain beautifully calibrated whether the figures are still or running amok. . . . Packed into Joe’s Pub for Dancemopolitan, we’re craning our necks to ogle the tiny corner platform that serves as a stage for the cabaret show of postmodern dance. Village Voice 3/29/05

DUMB SHOW

Matthew Bourne: Play Without Words / BAM Harvey Theater, NYC / March 15 – April 3, 2005

Matthew Bourne, who has relentlessly been creating new takes on golden holies (Nutcracker, La Sylphide, Cinderella, and—the one that made it to Broadway—Swan Lake), insists in interviews that his work, if it’s dance at all, is for people who don’t like dancing. Yet a number of well-known dance critics, both American and British, have been dancing around it, clapping their hands, and Bourne has won enough awards to require a dedicated trophy room. Now his Play Without Words—which copped an Olivier in 2002, when it was created for the Brits’ National Theatre—has come to town. I like dancing; should I have stayed home?

No one in his right mind would praise Bourne for choreography per se. The weakest element of Swan Lake, it is virtually absent from Play Without Words, which deals mostly in highly stylized mime pumped up with show biz moves, the mix paying little heed to musical structuring. Ostensibly Bourne’s appeal lies in his vivid theatricality and his transgressive bravado. (That flock of gorgeous, vicious boy swans in Swan Lake is typical.) I’m not entirely convinced, or entertained, by either.

Play Without Words takes off from Joseph Losey’s memorable 1963 film The Servant. The ominous screenplay by Harold Pinter tells—in words and even more provocative silences—the black tale of a privileged fellow who hires a “man” (a combination butler-housekeeper-valet) who, playing upon varieties of erotic desire laced with class struggle, proceeds to undo his master. Each of these chaps has a woman in his baggage. Our deplorable/unfortunate hero comes equipped with a fiancée, though neither member of that cold couple has the wits to acknowledge that the gentleman is, at the very least, bisexual. The servant, having made himself indispensable in the household, introduces his “sister” as a maid. The irresistibly provocative miss is, of course, the servant’s bedmate; her real job, to consolidate working-class power by seducing the boss, which she does, ironically, with genuine pleasure.

Play Without Words takes off from Joseph Losey’s memorable 1963 film The Servant. The ominous screenplay by Harold Pinter tells—in words and even more provocative silences—the black tale of a privileged fellow who hires a “man” (a combination butler-housekeeper-valet) who, playing upon varieties of erotic desire laced with class struggle, proceeds to undo his master. Each of these chaps has a woman in his baggage. Our deplorable/unfortunate hero comes equipped with a fiancée, though neither member of that cold couple has the wits to acknowledge that the gentleman is, at the very least, bisexual. The servant, having made himself indispensable in the household, introduces his “sister” as a maid. The irresistibly provocative miss is, of course, the servant’s bedmate; her real job, to consolidate working-class power by seducing the boss, which she does, ironically, with genuine pleasure.

Bourne captures none of the film’s Turn of the Screw atmosphere, its all but palpable air of half-concealed desire, corruption, and menace. His equivalents of the four main characters are tepid, sometimes two-dimensional to the point of caricature. He himself may have found his efforts insufficient, since he casts three dancers, often performing simultaneously, in each role. This persona-in-triplicate scheme makes for a crowded stage and some confusion, though it reveals Bourne’s ability to direct traffic in ways that are visually effective. He has also added a fifth persona, a hefty blue-collar guy who clearly can have any woman he wants, and does. (This character, Bourne’s publicist explained to me, is a composite derived from other movies of the period.)

The Losey film’s pervasive and haunting motif of the characters’ spying on one another translates largely as simplistic farce in Play Without Words. Still, a couple of Bourne’s scenes are clever and genuinely amusing, in particular a double duet of the master being undressed—for a bath, of course, what were you thinking?—and dressed by his man. One passage—in which man and master all but destroy each other, then reconcile—achieves some authentic human depth, making you understand that they’re the most symbiotic lovers in the piece. Yet for the most part, though Bourne is touted as being a dynamic storyteller, Play Without Words fails to convey its characters’ motivations and feelings. It doesn’t even deliver a clear plotline. No wonder the show often grows tedious. Yes, even the change-partners-and-dance sexual exploits involving the kitchen table.

The production boasts a pleasant jazz score by Terry Davies and a Red Grooms-ish set by Lez Brotherston who also provided the early sixties costumes, including stiletto heels that, astonishingly, don’t for a moment faze the handsome ladies in the show.

I’m left wondering if Play Without Words isn’t simply a sign of our times, in which the creative powers-that-be assume their audience needs to be lured by shock tactics—the raucous, the garish, the forbidden, extremes of novelty for novelty’s sake. Surely the insistent use of these means, which quashes the virtues of sincerity and subtlety, is self-defeating. Most of today’s audience is already beyond shock and, what’s more, benumbed by the ever-escalating onslaught.

Photo: Richard Termine: Sam Archer and Steve Kirkham as master and man in Matthew Bourne’s Play Without Words

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Ballet School

My bets for a glorious future are on Joseph Caley, a fresh-faced and courageous high flier who might be the hero of a child’s adventure story–prodigious in his skills, ingenuous in his beauty. Village Voice 3/15/05

GARBO GETS DRESSED

Glamour: Fashion, Film, Fantasy / The Museum at FIT, NYC / February 15 – April 16, 2005

Camille; directed by George Cukor; starring Greta Garbo, Robert Taylor, and Lionel Barrymore; gowns by Adrian; Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1936

Any theory that may lie behind Glamour: Fashion, Film, Fantasy, the current FIT exhibition curated by Valerie Steele and Fred Dennis, pales in face of its simple, captivating reality. It’s essentially a huge room peopled by row upon row of mannequins wearing gowns that, like the movies and the stars they’re associated with, provide a blessed antidote to reality. To make sense of this uninflected panorama of extravagant gorgeousness, you instinctively seek out a few objects (as the pros call them, though the word is a pitiful choice) that were meant for you—not for your body, but for your imagination. And then, inevitably, you zero in on the single one that speaks to you most particularly. Or—who knows, the art of costume employs so much witchery—perhaps it chooses you.

The item with which I bonded was a gown by Adrian, created for Greta Garbo to  wear in George Cukor’s Camille. Executed in black velour, it has a reticent cut—a demure sweetheart neckline, a snugly fitting bodice. From the trim waistline, a generous skirt falls with cushioned weight, extending slightly at the back as if to hint (only hint, mind you) at a train. A spray of black tulle capping the shoulders suggests a pair of wings, the gown’s sole concession to the frivolity of lightness. A modest “brooch” formed from bits of crystal and metal, is anchored dead center on the bosom, like a family heirloom dutifully displayed. But, shooting out a few slender bronze rays, letting fall a sprinkling of minute sparkles that might be stars, it introduces the idea of a celestial universe. This theme expands—explodes, actually—on the skirt, which looks as if a lavish and reckless hand had flung a galaxy across it. The glittering, gleaming incrustation contains clusters of crystals in myriad shapes—squares, rectangles, elongated diamonds, teardrops, five-pointed stars—and graduated sizes. Raised squares and domed circles are emphasized by marcasite-style frames, while flocks of small and even smaller pewter gray sequins create the illusion of stardust. This evocation of a galaxy recalls the work of Schiaparelli’s “Zodiac” collection (with its extravagant beading by the House of Lesage), but where Schiaparelli’s fantasy glories in its ostentation, Adrian’s treatment is more innocent, like something out of a child’s dream.

wear in George Cukor’s Camille. Executed in black velour, it has a reticent cut—a demure sweetheart neckline, a snugly fitting bodice. From the trim waistline, a generous skirt falls with cushioned weight, extending slightly at the back as if to hint (only hint, mind you) at a train. A spray of black tulle capping the shoulders suggests a pair of wings, the gown’s sole concession to the frivolity of lightness. A modest “brooch” formed from bits of crystal and metal, is anchored dead center on the bosom, like a family heirloom dutifully displayed. But, shooting out a few slender bronze rays, letting fall a sprinkling of minute sparkles that might be stars, it introduces the idea of a celestial universe. This theme expands—explodes, actually—on the skirt, which looks as if a lavish and reckless hand had flung a galaxy across it. The glittering, gleaming incrustation contains clusters of crystals in myriad shapes—squares, rectangles, elongated diamonds, teardrops, five-pointed stars—and graduated sizes. Raised squares and domed circles are emphasized by marcasite-style frames, while flocks of small and even smaller pewter gray sequins create the illusion of stardust. This evocation of a galaxy recalls the work of Schiaparelli’s “Zodiac” collection (with its extravagant beading by the House of Lesage), but where Schiaparelli’s fantasy glories in its ostentation, Adrian’s treatment is more innocent, like something out of a child’s dream.

The gown is quietly and extraordinarily beautiful. It also turns out not to have been used in the film. After much inquiry around town, initiated by a puzzled query on my part, it has been relabeled to indicate that it’s simply one of several variations proposed for the occasion. But I didn’t know that when I fell in love with it, and afterwards, as in most such affairs, there was no going back.

From the sheer pleasure of gazing at this object, I went compulsively further, as writers will. What could be more fitting for a dance fanatic, after all, than to screen the film for which the gown was designed, to see it in motion?

The wardrobe Adrian created for Garbo in Camille demonstrates the fantasy side of a designer equally renowned for the subtle, witty tailoring of ostensibly Plain Jane tweed suits. It is ravishing piece by piece. What’s more astonishing, though, is the use of the costumes, in sequence, as a metaphor for sublime beauty haunted—and finally extinguished—by death. (Should anyone in the Western world still be unaware of the fact, let me say that the heroine of Camille succumbs to TB—a scourge that art has somehow associated with high romance.)

Marguerite Gautier—the lady of the camellias, as Alexandre Dumas calls her in the novel that spawned not just this film but Verdi’s La Traviata and minor but poignant ballets by Ashton and Tudor—habitually arrays herself in the white of her signature flower. She may be a kept woman, we’re given to understand, but once she encounters Armand Duval she experiences genuine, selfless love, and the white comes to stand for the purity and innocence of romance free from corruption.

After their initial encounter, Marguerite invites Armand to her birthday celebration, to which, as we see first in close-up, she wears a gown that’s an enormous froth of white tulle, like beaten egg whites. It’s offset only by a single but striking ornament—a huge black bow pinned between her breasts like a “scarlet” letter, signifying death. Moments later, when she’s captured in a long shot, standing and then dancing, we see that both bodice and skirt are sparsely strewn with large glittery paillettes in the form of stars, an indication that the heavens are her inevitable realm. The gown’s drooping gauzy sleeves, dance aficionados will enjoy noting, might belong to the ethereal costume of a Romantic-era ballerina.

Further on in the film, another white gown—far less diaphanous than the first, as if the air had been sucked out of it—bears two smaller black bows, one under the other, like a sign with a definite yet still undecipherable meaning. Thin lines of black edge the shoulders, the décolletage, and the giggly puffed sleeves as well, like a warning—indeed, an omen.

Marguerite’s health deteriorates. She and Armand retreat to the country where they deceive themselves into thinking she will be cured by a life of idyllic simplicity and calm in the fresh air. In the horse-drawn carriage taking them to their rural destination, she’s swathed in a black coat and hat that refuse to reflect a single ray of light. Only a white scarf at her neck recalls a happier time. Black has become the dominant hue enveloping her, white reduced to a minor presence.

At the cottage, shortly before the arrival of Armand’s father, who will persuade Marguerite to sacrifice her love to her lover’s future, she wears a modestly long-sleeved, full-skirted white dress. As if to reinforce the image of decorum, the camera keeps steadfastly away from her throat, the locus, in other scenes—when Garbo flings back her head in abandon—of nudity abandoning itself to erotic pleasure. The chaste outfit in which Marguerite receives her lover’s parent—and submits to his request, which means ultimate self-sacrifice—is slashed by a black waistband anchored by a tight bow at the center, its long inky streamers streaking down the ballooning skirt with the assured ruthlessness of the incision made by a scalpel in the hand of an autopsy surgeon.

Attending the wedding of Armand’s luminously virginal sister, Marguerite extinguishes the white of her dress with a black bonnet and stole, to which she subsequently adds a black pelisse that might as well be a shroud. (White, after all, is for untouched brides, whom a wedding’s witnesses are forbidden to rival.) These cover-ups, very Victorian, are the only ugly garments in the film. Restitution will be made for this incursion by Garbo’s final costume, a pure white nightdress designer-cut for a saint. Standing to greet the lover returned to her at the last moment, the expiring heroine tucks a single white camellia into its waistband. In the black and white film the petals edging the blossom suggest the black borders on the creamy letter paper the Victorians used for death announcements and ensuing condolences.

Meanwhile, at the end of the scene in which, breaking her heart, Marguerite sends Armand away by telling him she prefers the man who formerly kept her, she wraps an enormous length of white fabric around her, turning her body into a narrow fluted column, a premonition of an effigy on a tombstone.

Now comes the passage I had been anticipating so eagerly. Having renounced her liaison with Armand, Marguerite has returned to the lover who previously supported her hectic life in the demimonde. She appears with her protector at a raucous soiree, where Armand, returned, encounters her just as she is being insulted by her escort. All cool subtlety, Armand reprimands his unworthy rival, then triumphs over him at the gaming table, making a killing at his expense. Then, in bitterness and barely contained rage, he hurls the money he has won at Marguerite, so that the huge, crumpled bills spill down the length of her dress.

I assumed that, in this scene, Garbo would be wearing the gown I’d fallen in love with at FIT. But no. She’s dressed in a gaudily elaborated version of it—the paillettes scintillating everywhere, the decoration on the bodice amped up, the black tulle that had been confined to the sleeves not merely augmented and fluffed out there but also extended over the entire garment, closely wrapping the gown and, by implication, the body, like the netting used to surround an offering of luxurious chocolates. Undeniably, this version of the costume is metaphorically correct. On the surface, Marguerite has been reduced to the status of luxury goods, available to anyone who can afford her. But the costume used in the film neglects the pathos of her situation, while the gown on display at FIT, grasping it so truly, is not merely beautiful but deeply touching as well. Of course, even to consider my claim, you have to believe that a dress—nothing more than a few yards of cunningly cut black velvet, a little jet tulle, and a shower of sparkles—can have emotionally persuasive power. The proposition can’t be argued. It has to be succumbed to.

Photo: Irving Solero: Adrian: Movie costume for Greta Garbo in Camille: Black velvet and tulle with beads and embroidery; The Museum at FIT; Gift of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc.

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

FIFTY YEARS OF HEAVEN AND HELL

Paul Taylor Dance Company / City Center, NYC / March 1-20, 2005

Celebrating its 50th anniversary with a tour to the full 50 United States, the Paul Taylor Dance Company is playing three weeks in New York City, its hometown. The repertoire encompasses a host of golden (and silver) oldies and a pair of new works. Newish, anyway; both had their premieres out of town.

Klezmerbluegrass honors an even more venerable anniversary than Taylor can lay claim to. The piece was commissioned by the National Foundation for Jewish Culture to celebrate 350 years of Jewish life in America. (The celebrants have in common the fact that it hasn’t been easy going.) It’s typical of the bemused perversity that characterizes Taylor’s mindset that the choreographer, while executing his commission, should combine the folk music of itinerant bands in eastern Europe with another folk genre: American bluegrass. What these two share, of course, is a vigorous dance impulse. Margot Leverett, who arranged the music and plays it (on clarinet) with the Klezmer Mountain Boys, has, indeed, arranged a reasonably convincing marriage of the genres. Taylor, maverick miracle worker that he is, combines them even more seamlessly in dance. If the resulting piece never digs deep into the human condition, as the best of Taylor does, it supplies a thoroughly enjoyable surface exuberance.

Klezmerbluegrass honors an even more venerable anniversary than Taylor can lay claim to. The piece was commissioned by the National Foundation for Jewish Culture to celebrate 350 years of Jewish life in America. (The celebrants have in common the fact that it hasn’t been easy going.) It’s typical of the bemused perversity that characterizes Taylor’s mindset that the choreographer, while executing his commission, should combine the folk music of itinerant bands in eastern Europe with another folk genre: American bluegrass. What these two share, of course, is a vigorous dance impulse. Margot Leverett, who arranged the music and plays it (on clarinet) with the Klezmer Mountain Boys, has, indeed, arranged a reasonably convincing marriage of the genres. Taylor, maverick miracle worker that he is, combines them even more seamlessly in dance. If the resulting piece never digs deep into the human condition, as the best of Taylor does, it supplies a thoroughly enjoyable surface exuberance.

Klezmerbluegrass opens with four couples doing square dancey stuff; the moment this registers, three more couples join in to give the lie to the restrictions of foursquare structure. This is an aspect of Taylor’s genius: He never dwells on the obvious; he simply states it briefly to give the viewer a firm reference point and then moves–swims, skedaddles, slips–on, creating variations on the theme so inventive he seems at time to depart from it entirely (though not quite).

The gleeful opening section gives way to a somber, melancholy dance for the work’s seven men, which cleverly uses the motif of line or chain dancing both as a structural device and a decorative one. One at a time, a single man emerges for the briefest solo stint in front of the moving wall, then lets himself be absorbed back into the quietly throbbing matrix of the tight-knit community.

A raucous passage, follows, led by Richard Chen See. Evoking wild–perhaps ecstatic–release, it’s succeeded, a tad too obviously (at this stage of his career, Taylor occasionally operates on automatic pilot), by a sultry female quintet led by Silvia Nevjinsky. Taylor has Nevjinsky evoke all the stock images of the houri, and she does so so beautifully and with such unemphatic conviction, they are somehow renewed. Chain dancing appears here again, with a single gesture spilling, wave-like, down the line and, at one point, a witty reference to Balanchine’s compulsive daisy chains. Eventually five men arrive to shadow the women, then partner them, as if to imply that the female display, which we took to be what women do (or discuss) in a private, intimate women’s world was, after all, only a device to attract the men with whom they’re destined to mate.

Next, logically, comes the obligatory “love” duet of the piece, but it’s more playful than romantic here, with the tiny Julie Tice becoming a plaything (albeit a feisty one) in the arms of the lanky Michael Trusnovec. At the end of their tête-à-tête, the two are held aloft and paraded around, mounted on the shoulders of the ensemble like the bridal pair at a Hasidic wedding.

As the dance winds down, Taylor gives us the “Ah, but . . .” with which he typically qualifies any proposal of the world’s perfection. The neatly coupled 14 dancers of the piece are joined by the loner, the outsider–here in the form of Annmaria Mazzini. She’s given a long, sensuous solo of yearning, tailor-made, if the pun can be forgiven, for her expressive power. I suspect–this is just on one viewing, mind you–that, choreographically speaking, the solo doesn’t amount to much, that its meanderings are charged with a sensuous melancholy Mazzini could project simply doing her daily exercises, but it grabbed my heart nonetheless. In the final moments of the dance, the ensemble returns, comforts Mazzini’s character a little, and allows her to leave. The point is quietly made, but made nonetheless: an effective social matrix must cast off the occasional person who doesn’t fit in. By definition, community has little space for the aberrant.

When Taylor turns out the pair of new pieces he assigns himself to create annually, he usually adheres to the practical formula of one upbeat, one gloomy. Dante Variations, set to music by György Ligeti, falls into the dark-night-of-the-soul category, with its pointed epigraph from the Inferno, its opening and closing frieze of recumbent writhing bodies, and its prevalent mood of torment and despair.

Early on, the fallen figures of the frieze struggle to their feet and move from a gray-blue gloom into a glowing peach-colored light that lets us witness, as if in the reflection from hellish flames, some particulars of their plight. Nevjinsky, however, remains in the ominous fog, futilely extending a pleading hand to a merciless fate; eventually she’s joined by three lurking men for couplings right out of Hieronymus Bosch. Elsewhere, a small crowd of figures reverting to their animal instincts surrounds Michelle Fleet (in happier circumstances, worthy of her surname), who sits on the floor as if rigid with fear, legs wide open. When the men in the group lift her high, displaying her as prey, she beats her thighs with her fists. Then this treacherous little community blindfolds her with a narrow length of white cloth, watches as she fumbles and staggers through a miasma of lost dimensions, and abandons her to grope her way out of our view, alone. The bandage-like strip of fabric appears elsewhere to thwart the body by “handcuffing” it at the wrists or knees–or, in a mistaken deviation into slapstick, tripping it up.

It’s only to be expected that the obligatory central duet, given to Trusnovec and Lisa Viola, should examine the antithesis of love. The two take turns in the dusky light and the bright glow. She’s frenetic; he’s riddled with shame and incapacity. Eventually they get together for a series of horrific moves that, again predictably, provides solace to neither of them. Their final flight takes them to opposite corners of the stage.

Everything Taylor makes his dancers do in this piece, he’s had them do before–with greater conviction and intensity. Looking uninspired and recycled, Dante Variations provides little illumination for its audience. But, while I don’t think this venture amounts to much, it did make me realize how much of Taylor’s work argues–and argues convincingly–that we humans are a breed of cripples aspiring to sublimity. Who, after all, so in need? Who, after all, so deserving?

Photo: Lois Greenfield: Silvia Nevjinsky in Paul Taylor’s Klezmerbluegrass

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Cathy Weis Projects

Impelled by her unabashedly maverick imagination, Cathy Weis melds dance, video, and the fact that she has multiple sclerosis into haunting theater pieces. Village Voice 2/22/05

Elisa Monte Dance; Configuration

Monte’s choreography is handsome and functional, but all her devices remain standard; on the Configuration program, only Harrison McEldowney’s “At the End of the Road” offered genuine joy and wit. Village Voice 2/22/05

RoseAnne Spradlin

I guess RoseAnne Spradlin has death on her mind. Village Voice 2/8/05

STAR TURN

Stars of the 21st Century / New York State Theater, NYC / February 14, 2005

Agrippina Vaganova’s showy Diana & Acteon pas de deux found American Ballet Theatre’s Xiomara Reyes, a pixie of a huntress, demonstrating how the body can represent at once bow, arrow, and archer, while her partner, Herman Cornejo (also from ABT) displayed the bravura technique, everywhere suffused with grace, that has catapulted him to the top echelon of today’s male dancers. Though he’s a stunning virtuoso, his performances have increasingly suggested a range and depth of feeling that might qualify him for the danseur noble category. He lacks only the height and princely good looks associated with that type; maybe it’s time to quit holding that against him.

Eleonora Abbagnato and Alessio Carbone drew the short straw when it came to choreography (though presumably the dancers had some say in what they performed). Their first number was a duet from Roland Petit’s L’Arlesienne, where the folkloric embellishments do nothing to conceal the lack of an authentic dance impulse. Though the material natters on endlessly, it never gets close to answering the question a baffled viewer might well pose: Is the soldierly gentleman’s problem conscientious objection or a more domestic difficulty that a dose of Viagra could resolve? (Neither, I found, after some post-performance googling, but, ripped from its larger context, the duet fails to tell its real story.) A second stymied offering, Mauro Bigonzetti Kazimir’s Colours, proved to be an exercise in angularities and gymnastic coupling, with little air allowed between the two bodies. The attempt to evoke Kazimir Malevitch and the abstract geometry of that painter’s Suprematist style, was surely a foolhardy undertaking; given the nature of the human body, the concept is impossible to convey. Nevertheless, being from the Paris Opera Ballet, the dancers executed both their assignments with an objective, impeccable purity that’s a phenomenon in itself.

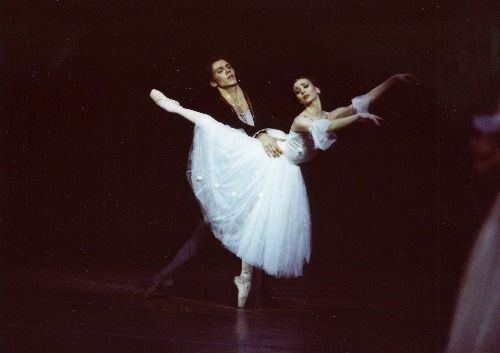

The celebrated partnership of the Royal Ballet’s Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg—she emerging as the most gifted ballerina of her generation; he the most sympathetic of partners—was showcased in the Act II pas de deux from Coralli and Perrot’s Giselle (which epitomizes the delicate, morbid, and sublime elements of Romantic dancing) and Petipa’s Don Quixote pas the deux (which demonstrates the fireworks element of the classical mode). I’ve had my say about this pair in these pages and their gratifying physical and emotional rapport. Just now, the much-feted Cojocaru needs to beware of exaggerating her effects in the gauzy Romantic style and to cultivate, if it’s in her, more of an appetite for the dazzling bravura feats she already commands. She can bring them off, all right, but she lacks the instinct for circus-style excitement.

Dancing the Rubies pas de deux from Jewels, Diana Vishneva and Andrian Fadeev, proved—if this still needs proving—that the Kirov Ballet can manage a reputable reading of Balanchine. Vishneva, in her effort to be echt American in the jazzy rhythms and free-flung moves, goes almost too far—yet the results suggest that she’s still imposing a Russian-school control on her material, simply at extravagant extremes. Fadeev, all boyish charm and correctness, must learn to burn brighter before he can accurately be termed a star, but he’s undeniably appealing. In the Balcony pas de deux—performed alas, sans balcony—from Leonid Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet (the granddaddy of the great R&Js), Vishneva was lovely if, as always, overly aware of the effect she wanted to make; Fadeev, again, a little too reticent. Both, though, deflected any serious complaint with the most beautifully shaped high-flying leaps imaginable.

The famous pas de deux from Le Corsaire teamed up the New York City Ballet’s Alexandra Ansanelli with ABT’s Angel Corella. Ansanelli is so petite and pretty, she can’t help simpering a little, but Corella, a virtuoso with a full complement of humanity to him, deserves more depth in a partner—and more technical precision. On this occasion some of Corella’s gasp-inducing feats looked a little forced, despite his irresistible combination of sunniness and wild-animal élan. Could it be that he has begun to grow insufficiently elastic for the murderous shenanigans? If ABT can’t provide him with roles to ensure his future as a mature artist, he might profitably consider going the Baryshnikov route. But I digress.

Munich Ballet’s Lucia Lacarra and Cyril Pierre received the evening’s heartiest acclaim, in two sensational numbers by Petit, whose forte is theatrically savvy melodrama: the bedroom pas de deux from Carmen and a pas de deux from La Prisonnière. Both items deal in poster-art eroticism, the latter as kinky as the Proustian situation on which it’s based. The dancers approached the material as if it were an exercise in style, and the results were duly effective, though I’ve seen realistic Carmens that were more moving. Needless to say, Lacarra’s exquisitely arched feet and fabulous leg extensions worked to great advantage in these assignments.

A pas de deux from Bournonville’s La Sylphide seemed to take place in two different countries as well as two different eras. The Bolshoi Ballet’s Svetlana Lunkina, costumed à la Marie Taglioni, evoked the nineteenth-century Romantic style that originated in France, dancing as if she were doing delicate embroidery. Her James, the National Ballet of Canada’s Guillaume Côté (a last-minute replacement for Lunkina’s scheduled Bolshoi partner), was a contemporary North American type—athletic in style, forthright in demeanor. Needless to say, the combination failed to transmit either the ballet’s scenario or its atmosphere, but each dancer had considerable charm in his own way.

For the first time, the Stars agenda admitted some modern dance—the powerful and poignant “Steps in the Street” section from Martha Graham’s 1936 Chronicle, staged by Yuriko for an eleven-woman ensemble of Graham pros. Perfectly structured, magnificently stark, forceful, and poignant, it was performed with just the right focus and fervor by the group, Stacey Kapalan at its head. Judging from its less than thunderous applause and the absence of the shouts that greeted the fouetté displays on the program, the Stars audience was underwhelmed, but at least it saw an alternative to its favorite mode.

There is no way to provide a meaningful finale for a smorgasbord event like this one because, in truth, it doesn’t add up to anything. This occasion concluded with something inaccurately called a défilé. After bows for each pair that seemed to milk applause readily awarded earlier and a comedy-of-errors presentation of some very pretty bouquets, the stars took turns crossing the stage with their most flamboyant feats. Don’t ask.

Photo: Nina Alovert: Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg in Giselle

© 2005 Tobi Tobias