Tense Dave’s neighbors (or fantasies) include an elegant sadist, a nightgowned damsel with extravagant suicidal impulses, a languid lady given to enacting the scenarios of Victorian bodice rippers, and a creepy fellow who does nasty things to small creatures in his spare time. Village Voice 5/31/05

Archives for 2005

Momix

Lunar Sea is not a dance but rather multimedia light entertainment for the eyes that blithely ignores engaging the mind or heart. Village Voice 5/24/05

THE BOURNONVILLE FESTIVAL, LOOKING BACK

2005 is the 200th birthday of August Bournonville, the dancer, choreographer and ballet master who gave the Royal Danish Ballet its distinctive profile. To mark the occasion, the company has organized the 3rd Bournonville Festival, which will take place in Copenhagen, June 3-11. All of the Bournonville ballets that are still danced today will be performed on the stage of the Royal Theatre, along with the codified classes devised to preserve the choreographer’s unique style. A host of museum exhibitions will complement these events. The first Bournonville Festival took place in 1979, the 100th anniversary of Bournonville’s death, and the occasion has become legendary. I wrote an account of it for Dance magazine (March 1980) that I offer here as background for the reports I’ll be making on the coming Festival. THE FESTIVAL IN COPENHAGEN It’s almost impossible to dismiss affection in talking about the Royal Danish Ballet’s dancing Bournonville. Perhaps one shouldn’t. To mark the centenary of the choreographer’s death, the company staged a week of performances, November 24-30, 1979, of the Bournonville ballets that have survived into the present: La Sylphide (1836), Napoli (1842), Konservatoriet (1849), Kermesse in Bruges (1851), A Folk Tale (1854), La Ventana (1854; 1856), the pas de deux from The Flower Festival in Genzano (1858), Far from Denmark (1860), and The King’s Volunteers on Amager (1871). Although August Bournonville is among the three or four pivotal choreographer-ballet masters of the nineteenth century, and indisputably the most significant figure in the history of Danish dance, the majority of these works are rarely seen complete outside their native environment. The mounting delight of the audience in the course of the week’s showings—culminating in jubilant ovations unprecedented in this sedate theater—established a bond among the spectators and between the spectators and artists that promised to be cherished and enduring. The audience was an international one: dance fans, scholars, and critics—Americans especially—converged on Copenhagen for the Festival. Nightly performances were given in the jewel-box Royal Theatre (built in the last years of Bournonville’s career), which allows an intimacy lost in our formidable opera houses. In addition, there was a profusion of complementary exhibitions and events. Among them, the Bournonville collection assembled at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts was a miracle of particularizing and revivifying the past—through its displays of costumes and stage designs, convoluted manuscripts and diagrams that notated the ballets’ choreography and production details, the brown-inked diaries that became My Theatre Life (the choreographer’s autobiography, recently published by Wesleyan University Press in Patricia McAndrew’s long-awaited English translation), the raised chair from which Bournonville oversaw classes, his ballet-master stick, and old postcard-photos of several decades of performers. Depicted among these charming souvenirs were Juliette, Sophie, and Amalie Price, for whom Bournonville made the affectionate Pas des Trois Cousines, and their descendant, Ellen Price, the model for the statue of Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid, who gazes out wistfully over Copenhagen’s harbor. Some forty ranking professionals (one wishes the protocol had been somewhat more relaxed) were also treated to events such as a lecture-demonstration by Kirsten Ralov (the company’s assistant director) on the raked stage of the old Court Theatre, where Bournonville danced as a boy, and to a fascinating inch-by-inch tour of the present theater. This visit disclosed an intricate backstage world with inventive, old-fashioned mechanics for stage magic—the device that flies the Sylph heavenward, for example, complete with its two child-sized safety harnesses for her attendant sylphlings. There were videotape and film screenings of Bournonville-related material, ranging from the Peter Elfelt fragments showing Royal Danish Ballet dancers at the turn of the century, through homemade footage of the “lost” Romeo and Juliet Frederick Ashton choreographed on the company in 1955, to contemporary television productions tackling the subject of “Bournonville now.” (This is a thorny problem for the Danish dance world, which tends to be ambivalent about its national treasure.) Aside from lively intermission conversations, there were impromptu convocations (fueled by supplies from the all-night smørrebrød shop) to marvel at and argue about what was being seen and formal receptions glowing in their traditional Danish candlelit welcome. One felt embraced by the occasion. And then there was the city itself. Copenhagen is a walker’s town. One comes to believe, without much exaggeration, that one can encompass the entire city on foot, strolling from the Town Hall Square with its landmark clock-in-the-tower, to the Royal Theatre at Kongens Nytorv, to the antique-and-rare-book haunts of the University Quarter; from canal to harbor to the park-with-a-windmill built on the spiraling city ramparts. The major streets are graciously wide, with long stretches closed to traffic; these are lined with shops, many of which specialize in gleaming china and glass dining ware. The main thoroughfares branch off into crooked byways that invite you to discover, serendipitously, the charm of an old house—a tiny, turquoise-tinted row house, perhaps, where Hans Christian Andersen (a would-be ballet dancer once, and Bournonville’s friend) lived for a decade, or tranquil Old World courtyards overlooked by the windows of fastidiously cared-for homes. The predominant style of architecture is a Dutch Baroque, which gives any building short of a palace a cottagey look. The palaces themselves—the Amalienborg, where tin-soldier sentries pace up and down, guarding their queen, and Christianborg Castle, which might be the setting for a medieval fable—are human in scale, as is everything in the city. The Round Tower, designed for astronomical observation, is a mere 115 feet high. The bourgeois temperament prevails everywhere: While Copenhagen is undeniably one of the world’s pornography capitals, the pharmaceutical matter-of-factness with which sexually titillating devices are displayed is more amusing than arousing, while subtler examples of eroticism are rather like the sculpture chosen by the Glyptotek Museum for its house poster—Gerhard Henning’s Reclining Nude, ingenuous in her sensuality. The complement of this snug, delectable comfort and human proportion is the sudden incidence of chimerical architecture—the Stock Exchange, built for sober, pragmatic transactions, is crowned with the twined tails of four copper dragons—and of sites like illusions: rising out of nowhere there’s a cobblestone hill, studded with slender, gnarled trees growing out of little clearings. The November weather was characteristic of early winter in Scandinavia: wet, often stingingly cold, the daytime sky taking on the silvery gray-green tinge of the nearby sea. By four each afternoon, the long, luminous twilight had set in and a sliver of moon hovered over the dark, grooved roofs of the city. Intriguing as it was to walk by the hour in this strangely silent fantasy land, it was then all the more pleasant to come inside and envelop oneself in the peculiarly Danish hearth-culture, where heat, light, the hospitality of the table, and easy, open friendliness provide not just homely luxury but a sense of immutable security.

Bournonville’s ballets do constitute a special—and inimitable—kind of theater. The classical-dance element of it, which has been excerpted for presentation to audiences in the

Of the works shown in the Festival, Konservatoriet best elucidates the choreographic intelligence Bournonville exercised with this material. Using a demonstration of the danse d’école as its pretext, the ballet begins by slyly captivating the eye with its nostalgic pictorial evocation of a Parisian ballet studio in the Romantic era. It strews visual cameos throughout—typically, fragile jeunes filles in gossamer skirts, bending to tie the ribbons of their pointe shoes. But dancing itself is predominant from the very first moment, which introduces a company—in a devilish unison adagio combination—and proceeds by means of a chain of little cluster dances. A duet for a pair of women, which begins in canon and segues into unison, is followed by a trio, then a second duet—now for a man and a woman—and so forth. The edges even of the solos seem erased, so that the singled-out performer flows from, and back into, the ongoing wave of activity. The groupings mildly imply information about relationships—for instance, that of the faintly peacockish ballet master to a pair of sisterly yet rivalrous prize pupils. But the dance material demonstrates what this assemblage of people has in common: Konservatoriet is a ballet about ballon.

La Ventana, a chamber ballet, evidences the same choreographic sagacity. It is a suite of fiery but chaste Spanish-influenced dances, linked by an anecdote. A señorita is presented in a witty version of a venerable theatrical trick: She and her mirror-image double often move back to back, maintaining the “reflection” without eye contact. Next we have the solo unabashedly made to show off the señorita’s charms—the élan of her dancing, as much as its technical prowess. Then we meet her admiring señor, a trio of their “friends” who supply the virtuoso turn (with its treacherous pitched arabesques, its redoubtable batterie and aerial work), and a small ensemble that serves as a kind of animated-scenery back-up. The remarkable thing about this epicyclic construction is that the organization of the dance appears utterly causal on the surface; interestingly, the work had its genesis as a pièce d’occasion.

The ballet’s use of local color is typically Bournonvillean—a benign, tamed version of the Romantic artist’s longing for the exoticism of faraway places. (Similarly, La Sylphide is set in the Highlands, Kermesse has a Dutch locale and flavor, while Napoli, like several other Bournonville ballets now lost, takes its inspiration from

One of the points brought home by the Festival was that the most inventive and seemingly self-contained of Bournonville’s pure-dance sequences acquire an added dimension when they are seen embedded in the ballets to which they belong. Flower Festival in Genzano has fallen into regrettable—perhaps reprehensible—oblivion, so its lovers’ duet, a favorite in the international repertory, could be presented at the Festival with no supplementary information beyond what two very different casts might

afford. By contrast, the complete production of Kermesse in Bruges exposes the narrative and emotional significance of what seem merely grace-note gestures or congenial spatial designs when its popular Act I pas de deux is performed out of context. The hands extended and withdrawn, the young man’s and woman’s leaning toward each other, then traveling sideways to meet, cross, and retreat, only to step forth again with burgeoning confidence, are all part of the characterization of shy lovers-at-first-sight.

Similarly the Act I ballabile of Napoli, which seems happily self-sufficient in the contextless Bournonville Divertissements Stanley Williams staged for the New York City Ballet, tells us a great deal about Bournonville’s sophisticated strategies of story-weaving and multi-layered construction when it is presented in its intended surround. The dance, dense with interest in itself, serves also as a matrix for the plot. Threaded through its craftily varied group-dance expressions of youthful joie de vivre are the crucial steps in the story: the hero and heroine’s departure for a midnight sail that will end in an encounter with the supernatural and near-tragedy.

Elsewhere in Bournonville’s ballets, it would seem that pure-dance sequences are inserted merely to provide that type of heightened—athletic and highly stylized—dance interest, because of a felt need on the choreographer’s part, or simply to complete the menu of movement ingredients at a given point. In this category I’d put the third act pas de deux of Kermesse in Bruges, the gypsy pas de sept in A Folk Tale—both masquerade, a bit flimsily, as “entertainment” within the situational structure—and the pas de trois in the second act of The King’s Volunteers. These entries strike me as nearly superfluous in their context, given the more organic meshing of the other components and, particularly, the richness of the mime. An idiosyncratic opinion, no doubt, but then I’m repeatedly astounded by critics who applaud the “real” (read bravura) dancing in Bournonville and find the mime dull. It seems to me that if you’re not intently interested in the mime element in Bournonville’s ballets, you can’t possibly like, or even comprehend, Bournonville’s theater.

The most exquisite and sustained illustrations of Bournonville’s nuanced use of pantomime are the first acts of his surviving “vaudeville ballets”: the deliciously bizarre Far from Denmark—which culminates in a series of guilelessly defamatory dance cartoons of national types (nose-rubbing Eskimos, raunchy American Indians)—and The King’s Volunteers on Amager. In both, an entire story is unfolded in leisurely mimed conversations. These gesture colloquies move to the music in phrasing that is rhythmic, but more relaxed and irregular than that of dancing; it makes you think of a spoken song. As in Frederick Ashton’s Enigma Variations, which is the only dance work I know that is anything like these, the action proceeds in vignettes delineating ordinary and rather unemphatic behavior that is intermittently flooded with deep feeling. A poignant sequence in Far from Denmark begins with the delivery of the sailors’ mail: The second of a heartbreakingly young pair of cadets gets no letter from home; turning to the piano to assuage his grief with music, by bittersweet irony he plays an accompaniment to the luckier cadet’s reading his letter. And, from the shifting play of expression over that dancer’s face, you can guess the contents of the page, word for word. (I should mention here that the sociable dimensions of the Royal Theatre allow you to “read” the performers’ faces, and their smallest gestures, from nearly every seat. The dancers behave accordingly; no detail of the pantomime is falsified by being pushed.)

In the more complex and ambitious King’s Volunteers, the drama of the story is seamlessly woven into a double layer of daily household pursuits: Two interrelated planes of activity are visible at once—a hearth-warmed indoors and a snowy outdoors. This is not simply a lovely bit of craftsmanship. An observation is being made of how people’s little romantic adventures—meaning anguish or ecstasy to them—slip with only the slightest ripple into the ongoing, workaday life of a community. The sum of Bournonville’s extant works clearly indicates that this choreographer put a moral value on the stability and continuity promised by middle-class homeliness. In these mime scenes an artistic value is implied too. In the loving depiction of commonplace detail, Bournonville shares the pleasure and wonder evinced by the seventeenth-century Dutch genre painters in “the thingness of things.”

The second act of The King’s Volunteers, in which the romantic plot winds through a communal Shrovetide celebration, reinforces these ideas and posits yet another, again typical of Bournonville: that of dancing’s being the perfect metaphor for people’s personal and social intercourse. In a paradigmatic sequence, a ring of chairs occupies the major, central portion of the stage. Prosperous elderly peasants dance around it, then plump themselves, breathless, into the seats to watch a bevy of blooming young women and men perform a hoop dance. This group next separates into couples, who turn their U-shaped wreaths so that pairs of children—a third generation—can jump them, as if skipping rope. Finally the three generations join for a round dance, their concentric, counter-revolving circles an emblem for the group’s vigor and unity, yet never to the point of subsuming an individual body type or character or relationship—the stringy-figured, prissy-mouthed lady, for example, and her reluctant husband, grouchy and sciatic when he takes his wife’s hand, but already ogling his next partner.

All kinds of dancing are represented in this second act of The King’s Volunteers—with the emphasis aptly on the “folk” sorts—against a background of diverse human types engaged in eating, drinking, music-making, and conversational by-play. The drama builds to a climax in a burlesque dance laden with irony and is resolved with a long look exchanged by the two principals who are noticeable at that moment just because they are the only motionless figures on the stage. As with comparable passages in the Bournonville repertory—the opening and closing scenes of Kermesse come particularly to mind—you feel you can take in barely a tenth of what is going on; repeated viewings prove how carefully arranged and modulated these fecund stage pictures actually are.

For all the richness of the world Bournonville creates, there are worlds apart that he pointedly ignored. Missing from Bournonville’s theater is any sustained grappling with the elements of the erotic and the demonic with which most of the major Romantic inventors intuitively connected—and reveled in. Perhaps the vein of prudishness in his Biedermeier temperament that is acknowledged in his autobiography steered him away from the imaginative lures and presumed dangers of such material. Only in La Sylphide, which belongs to a relatively early phase of his choreographic development, does Bournonville come to grips with these subjects: In what can be taken as a parable of the artist’s pursuit of his muse, James forsakes the domestic security assured him in marrying Effie—his sweetheart in the prosaic world—to pursue the Sylph who represents the other-world of dreams and forbidden desires. He does so to his peril. It is only in this, of all his known ballets, that Bournonville allows an evil (personified by Madge, the witch who may in fact be the Sylph’s alter-ego) virulent enough to produce tragic consequences.

There’s no denying that, by following the path he did of sanguine sobriety, Bournonville cut himself off from a fertile area of creative investigation. I wonder, though, if an artist steeped in the turbulence and soul’s-jeopardy of the prevalent Romantic vein would have been capable of a work as singular and enchanting as Bournonville’s A Folk Tale. It is as shimmering, delicate, and self-contained as a soap bubble—the product of a unique imagination.

The argument of the ballet is a fairy-tale staple: an exchange of infants from dichotomous backgrounds who grow up to uncover their true nature. Here a human child of the gentry is secretly replaced in her cradle with a baby of the troll colony that lurks, half-hidden, in its under-the-mountain (that is, subconscious) domain. The switched girls grow to maidenhood, each instinctively revealing or seeking her roots. Although the human Hilda is promised by the dowager troll to the more loutish of her two sons, she yearns for an ideal goodness, which the ballet symbolizes, endearingly, by Christianity and the handsome young hero, Junker Ove. On the other hand, despite the gentility of her upbringing, Birthe remains a troll at heart and, aptly, in body. In one of the ballet’s most entertaining and psychologically keen sequences, she dances before a full-length mirror, in narcissistic, lyrical phrases—into which contorted troll-motions break uncontrollably.

The ballet contains a vestige of the themes of Romantic preoccupation—in the elf-maidens (a cross between the wilis and the nightgowned muses-with-flowing-hair in the Élégie section of Balanchine’s Tschaikovsky Suite No. 3) who emerge from their mountain caverns and swirl through the dry-ice fog to entrap Junker Ove, and in Ove himself, a sketchy indication of the morbidly dreamy temperament of the model Romantic hero. But the ostensible villains of the piece, the troll folk, feel harmless—because they are so quaint. (The second brother eventually grows as lovable as one of Snow White’s dwarfs.) This is a common folkloric device—subverting the potency of figures of mystery and fear by rendering them whimsically. But the real mark of Bournonville’s genius is that, at the same time, he is able to make the entire troll community a riotously accurate personification of the human race in its less attractive guises. I’m particularly fond of the show of self-congratulatory indulgence in the minor vices revealed at their orgy, but Bournonville’s deftest shaft may be in making the most characteristic attribute of these appalling creatures their bad manners.

Of course Bournonville, that inimitable proselytizer for joy, gives his story a happy outcome. What is remarkable about this closing scene in A Folk Tale is that one is wholly disarmed by the sweetness and purity of his means. The ballet ends, naturally, with the wedding of the lovers made for each other, Hilda and Ove. Imagine this sequence of images: six very young women (blond nymphets in pale green dresses, holding blossoming branches) softly waltzing; a slow processional, bland as a walk, for the wedding party, under wreaths of flowers; then, oddly slowed, the simplest of love pledges—the hand to the heart, then extended to the partner; a brief dance around a pastel-ribboned maypole; and the final assertion of the dulcet waltz motif accompanying a flurry of rose petals. Few artists could work with such trusting innocence.

The essential importance of the Festival for an observer new to the complete existing Bournonville repertory was simply to introduce the materials; a visiting critic’s first task was to understand the nature and scope of the ballets, not to attempt decisive judgments about their presentation. Still, some sort of evaluation of the productions and performances may be in order here.

Unfortunately, the primary question—that of authenticity—cannot begin to be answered by a foreign critic. It’s a hazy one even for Copenhageners. For lack of a continuous performance life in the Royal Danish Ballet’s repertory, many of Bournonville’s works have been lost altogether or eroded and altered. Even the scant documentation available to Danish-illiterate investigators tells us that substantial changes in the ballets have occurred through successive attempts to make them “more relevant to their times.” (This usually mean beefing up the technical virtuosity and cutting the mime.) Even the traditional and faithfully intended process of dancer-to-dancer transmission distorts choreography, in ways that are particularly invidious because they are at first nearly imperceptible. One wishes those responsible for the ballets over the decades had made a more conscientious and thoroughgoing use of notation and, when the media became available, film and videotape; one also wishes they had loved the works more.

Given the vagueness of our knowledge of what is echt Bournonville, it would be impudent for me even to say, This looked stylistically correct, that seemed false. It was a warning that the most incongruous-seeming piece of acting in the Festival, Arne Villumsen’s Bolshoi-style histrionics as Gennaro in

I think most of us who visited

It’s safer and easier to talk about today’s Bournonville dancers. Axiomatic in the theater is the fact that casting will please only some of the artists and viewers concerned, and the casting of the Festival performances was no exception. Often it appeared illogical, unjust, even perverse. American dance observers, introduced to the excerptible portions of Bournonville danced by the small, independent touring group of RDB dancers, may have come to

On the other hand, the casting of Frank Andersen, whose classical dancing is rather craggy, in the character part of Gurn in La Sylphide—a role he invested with new sympathy—seemed to open a promising avenue for his development. The company’s finest male classical dancer is indisputably Ib Andersen, and he’s of the caliber of his illustrious predecessors, Peter Martins and Erik Bruhn. The Danish critics like to call him a typical Bournonville dancer, because of his vitality in allegro, but I think the clarity and brilliance that’s epitomized by the sizzling stretch of his legs and feet, coupled with his long, rangy line and casual style, make him a natural for the New York City Ballet, which, indeed, he joins this spring. Perhaps in anticipation of this event, he was relegated to leading the classical inserts in several works—where he shone consistently—and allotted only one fleshed-out role, the male lead in Kermesse, which he played with appropriately reticent charm.

If we are to predict by favor in casting, the company has picked Arne Villumsen as his intended successor. To me, Villumsen is one of those dancers who is all gift and no desire. He is tall, ideally proportioned, handsome in a jet-haired, olive-skinned, sleepy-eyed way that would give him Gennaro in

The Festival introduced foreign viewers to a number of ascending female dancers, among them Ann Kristin Hauge, notable for her pertness and sparkle, and the ground-skimming Heidi Ryom, who stands out even in a company full of audience-charmers. At present the RDB’s great white hope is the twenty-three-year-old Lis Jeppesen, who made an enchanting Hilda in A Folk Tale by playing nothing more than her own ingénue qualities: April freshness, downy softness and airiness in the dancing, and a canny use of her wide-set dark eyes, which made the changeling girl’s mime utterances, with their artless, impulsive emotions, precise and telling. The Danish critics are besotted with Jeppesen; I don’t yet see the artistry or the formidable technique they’d claim for her. I didn’t think she displayed the dance imagination required for the title role of La Sylphide—somehow she seemed only human, in spite of her gauzy dancing—and I suspect she can’t turn very well.

I had the feeling that Jeppesen’s star was rising at the expense of Mette-Ida Kirk (who was the company’s princess-apparent on the 1976 American tour). In the Festival week we saw Kirk as Hilda in one of the two immaculate, performance-like dress rehearsals of A Folk Tale to which critics were invited and as Eleonora, the shy young heroine of Kermesse in Bruges. While Kirk hasn’t the advantage of Jeppesen’s kittenish prettiness, her dancing is a marvel of clean-cut precision—almost to a fault, actually. You wish she’d relax and flow a little more—explore an elasticity she seems to display only inadvertently.

The Folk Tale rehearsals that were so important in allowing the visiting critics to learn an unfamiliar and utterly delightful ballet better than a single performance could permit also gave them an opportunity to see Annemarie Dybdal, in the alternate cast, as Birthe, the troll girl. Dybdal’s attractive solidity and exuberance suited her to the juicy role, which she performed with intuitive respect for the richness and integrity of the ballet’s style. Linda Hindberg took the part at the official performance and camped it. The week gave us rather more Hindberg than was necessary. Her slangy style is just right for her long limbs and sultry face and it contrasts refreshingly with the Danish Ballet’s customary rounded-and-polished manner, but her technical reliability is uneven. A lot of the time she’s exhilaratingly on target, but she’s careless about intermittent wobbly approximations.

On the whole, the company is weakest when it comes to the sheerly technical aspect of classical dancing. Although solo performers are more often than not adequate to the occasion, if not triumphant at it, you’re never confident that the ensemble is reliable through and through in terms of exactness and strength in allegro dancing, of fluidity, equilibrium, and purity of line in legato movement. Bournonville’s pure-dance sequences were performed with ravishing accuracy and aplomb one night, indifferently the next.

I presumed the reasons for this might be apparent in the classroom, particularly since the Royal Ballet’s classes—both the school’s and the company’s—are customarily firmly closed to observers. (A Danish colleague told me he’d been unable to see Stanley Williams teaching until Williams—the Danes’ most gifted and influential pedagogue since Vera Volkova—emigrated to the

Neither class was the sort of truncated, carefully restrained tune-up affair common in our native companies during a strenuous performance season, but a thoroughgoing workout in which the dancers were evidently applying themselves seriously to correcting and expanding their technique. Everything was very finished and complete, beginning with a a calm methodical barre which, most noticeably in the women’s class, was faithfully executed with every last complementary port de bras and tilt of the head. A sober-spirited mood of daily drill pervaded both classes—a kind of civil-service atmosphere—which was offset here and there by a senior ballerina’s exquisite narcissism, the avidity of a handful of ambitious newcomers, a mischievous soloist’s giving a rakish twist to every other exercise, and Niels Kehlet’s dancing his entire barre.

Although neither session was one of the codified Bournonville classes, the ostensibly “international style” men’s class included many elements of the Bournonville school: an emphasis on accuracy and speed in footwork, combinations that included unsupported grands pliés and frequent unexpected volte-faces and that characteristically alternated light, small, beat-laden steps with broad, forceful leaps. Bournonvillean too were the equal emphasis on inside pirouettes, the dead-stop finishes in an immaculate fifth position, and the self-contained demeanor of the body in its shroud of personal space.

The men’s class was dogged but consistently interesting in its dynamic variety and the challenge issued by the demanding enchaînements; by the final twenty minutes only a third of the participants were capable of executing them. No specific attention was paid to pointe work in the women’s class—although the dancers are conspicuously deficient in this area, even granted the fact that a relaxed foot is attractive in the Bournonville work. I thought the session maddeningly foursquare rhythmically, but the dancers seemed not to notice; aside from one or two veterans who slipped out after the barre, the rest kept up with alacrity, struggling good-humoredly with some gargouillades, until the end.

A great distraction for me, in analyzing what I was seeing, was not just that the exposure was so curtailed and my naïveté about the milieu still so enormous, but the very novelty and pleasure of being there—the sense I had of layers and layers of history suddenly being animated. (Jørgen Leth’s recent film, On Dancing Bournonville, offers a view of the Degas-picturesque classroom, with its walls washed a soft gray-green, its elevated wooden dance floor that is like a miniature stage, complete to the lithe female dancers hauling away the moveable barres before the center work begins.) Watching the men fly across the space in huge assemblés and cabrioles, or hurtle in turning leaps straight downstage toward the observers as they do in the Napoli finale, seeing the succinct perfection of their small batterie executed in unison, watching the women zigzagging neatly two by two in feathery brisés—I found my judgment, already muted by the resonance of the past, suspended by the sheer kinetic wonder of the moment. In retrospect I can see that there may be a significant degree of incompatibility between the requirements of Bournonville dance and the Russian Vaganova training, that the orderly security and insularity of the Danish dancers’ situation may hold them back from daring certain levels of achievement. I doubt that I would have thought that five minutes after either class, though.

While the company may not be as athletically brilliant throughout as other world-ranking troupes, these dancers surely possess the most ingratiating and human manner of all. The unassuming modesty and frankness with which they present themselves is singularly refreshing in today’s dance world, which seems more and more to sustain itself on damn-it-all bravura and egocentric charisma. By contrast, the personal charm of the Royal Danish Ballet’s dancers is natural and reticent, as understated as their dancing. A viewer in their theater hardly notices the process through which his feeling of friendship with these artists grows into intimacy, it is so gentle and unforced.

One of the chief glories of the company is still its mime work. I don’t know that there are currently any virtuosi of the caliber of Gerda Karstens (now retired from the RDB). Just her photograph in the Royal Theatre’s retrospective as Madge in La Sylphide—a disheveled, gat-toothed, half-crippled old woman demonically laughing and gesticulating—is amazing in its reality and power. Still there were, continually, gratifying illustrations of the loving attention paid to mime work. In a single ballet—Napoli—half a dozen adroit dancer-actors appeared in hilarious, meticulously observed characterizations: Fredbjørn Bjørnsson’s endearingly gross macaroni seller, for example, hopelessly vying with Henning Kronstam’s lanky, only slightly cannier lemonade vendor for the flawless Teresina’s hand, and Niels Bjørn Larsen’s goggle-eyed street singer, soundlessly belting out his aria.

If I had to single out just one mime for verve and range, I think it would be Lillian Jensen, for her apple-cheeked farmer’s wife in The King’s Volunteers—the waddling, bobbing walk alone is masterful; for her earthy, self-possessed, petit-bourgeois mother in Kermesse, rubbing her hands together with cheerful greed when a pair of effete noblemen flirt with her daughters; and, above all, for her Muri in A Folk Tale, where each succeeding moment is a perfect accretion to her portrait of a flamboyantly vulgar troll matriarch whose deplorable instincts are absolutely human. In several ballets Mona Jensen seemed typecast as her counterfoil, in roles requiring a nun-like countenance and the kind of serene deportment that stands for unadulterated goodness. It was a wild and rewarding departure, then, to have her as the outrageously caricatured Creole inamorata non grata in Kermesse, padded out to opera-diva amplitude, flashing her garish train and maquillage as she swept along in pursuit of her wayward lover.

All of the mimes mentioned so far are past their strenuous dancing days, as are Solveig Østergaard, who gave us a gay and unembarrassed reading of the blithe, eye-rolling Medea—Bournonville’s innocently racist concept of a Negro servant—in Far from Denmark, and Sorella Englund, who played an unusual Madge, which she seemed to have built out from her body; her witch was long and bone-skinny, with a nervous, hysterical personality to match. The performance of these former ballerinas was satisfying evidence of the continuity a performing career in this company can have—beyond the dancer’s physical prime.

Perhaps the most touching example of this was the appearance of Kirsten Simone (the company’s prima of the 1960s) in The King’s Volunteers on Amager, as Louise, the wife temporarily betrayed by her husband, Edouard, who is an incorrigible ladies’ man. The sweetness and perfume Simone gave the character—entirely through mime—related directly to the stage personality she once projected through dancing. Her maturity and considerable beauty lent an interesting weight and autumnal sadness to the character’s situation without making it cloying or over-dramatic; the ballet is, in the end, a comedy, and Simone astutely brought off the fleeting changes of mood—the impetuous, mischievous inspiration, for instance, with which Louise resolves the affair, tricking her fickle husband into falling in love with her once more.

Simone was wonderful again as the rich widow in the final scene of Kermesse, where an entire village of characters is forced to dance uncontrollably and without respite—for her comic abandon. The willingness of the company’s “aristocracy” (Kronstam, the director and a former danseur noble, and Niels Kehlet, one of its greatest virtuosi, must be praised as well) to accept comedy’s most exacting challenge—allowing oneself to appear absurd—is as commendable as it is rare.

The richness of the mime element in the Bournonville ballets is not solely the creation of gifted individuals. In the famous crowd scenes—of Napoli, say, and Kermesse—it depends upon the action and interaction of the entire company, augmented by experienced extras, many of whom have been supering in these ballets since their university days. In the Festival performances the celebrated third act of Napoli was somewhat frozen, compared to the 1976 performances at the Met, in which every bystander seemed to have a name, an occupation, and a history, but Hans Brenaa’s staging of Kermesse was well-nigh perfect both in its mass effect and its detail. (This production and Kirsten Ralov’s mounting of A Folk Tale beg to be shown abroad while they are still fresh.)

The children of the venerable ballet school attached to the Royal Theatre are an intrinsic part of these scenes, displaying a beguiling combination of naturalness and precocious theatrical skill. It’s difficult to believe that the distorted little bodies and rude personalities—each carefully individuated—of the troldbørn in A Folk Tale belong to the same youngsters who appear as beautifully bred miniatures of the Romantic ballerinas and danseurs in Konservatoriet: sober-faced boys with already remarkable jumps, girls with corn-colored hair, grinning as they fling their legs ear-high.

Another of the company’s trump cards is its wholehearted concern and flair for the folk dance materials with which Bournonville flavors his works. The balleticized Spanish dancing in La Ventana, the Italian tarantella in

Photo: August Bournonville, painting by Carl Bloch, 1876. Courtesy of the Royal Theatre,

© 1980 Tobi Tobias

Nrityagram Dance Ensemble; Andrea E. Woods/Souloworks

Dare I say that the show sometimes seems unreal in its surface perfection, as if the irregularities and ambiguities that make art and life profound had yielded to Disneyfication? (Nrityagram); Andrea E. Woods may be essentially a solo performer–as Souloworks, the punning title of her enterprise, indicates–but she has a steady partner in the rhythmically cut, boldly angled video footage she creates as accompaniment. Village Voice 5/16/05

STAYING POWER

Jock Soto retires from the New York City Ballet’s stage on June 19 at the age of 40, after 25 years with the company. For the latter part of that period he has been extolled as a partner—as if that were his main (even sole) virtue, as was, essentially, the case with the company’s Conrad Ludlow in the past and Charles Askegard today. Yes, Soto’s an astute, often sublime, partner, but—having been around when he first showed up at the School of American Ballet and set the corridors abuzz with excited whispers: “Have you seen the new boy? Down the hall, taking class. He’s amazing !”—I think back to him as a dancer.

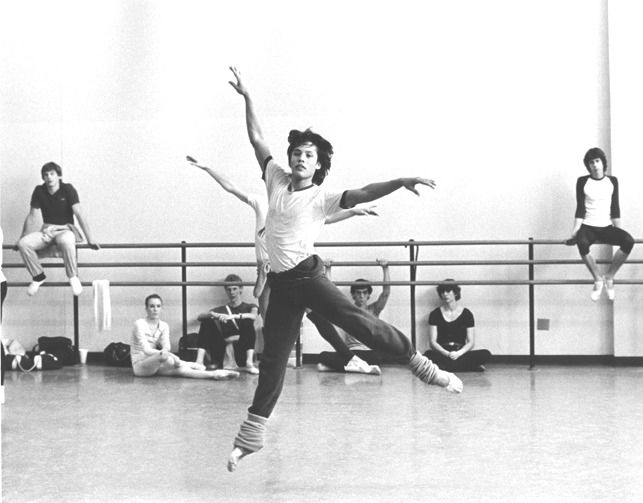

Memory is a tricky thing. Led by sentiment—for an artist’s personality, for the  terrain on which he operated, for the sheer accumulation of history—it can transform dross into gold. So I looked for more concrete evidence of the qualities I remembered in Soto from the early part of his career and found them, where you can see them too, in a videotape of The Magic Flute, choreographed by Peter Martins for the School of American Ballet’s Annual Workshop Performances in 1981. It was right after these performances that Balanchine invited the 16-year-old playing Luke, the male lead, to join the corps of the New York City Ballet.

terrain on which he operated, for the sheer accumulation of history—it can transform dross into gold. So I looked for more concrete evidence of the qualities I remembered in Soto from the early part of his career and found them, where you can see them too, in a videotape of The Magic Flute, choreographed by Peter Martins for the School of American Ballet’s Annual Workshop Performances in 1981. It was right after these performances that Balanchine invited the 16-year-old playing Luke, the male lead, to join the corps of the New York City Ballet.

The ballet itself is a charmer. Like Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée, the model of the genre, it’s a romantic pastoral comedy. Martins adds to the mix a commedia dell’arte element that he no doubt absorbed in his youth from the traditional pantomimes given in Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens.

The adolescent Soto recorded here is utterly disarming, and not just because of a frank, luminous smile that is well-nigh irresistible. Of course there are plenty of raw edges in the performance. He’s gawky here and there, unpolished, impetuous, giving himself over to a very simple joy in the moment. You could say he’s only a kid, though no adolescent in serious training for a career in ballet can be simply a kid. Granted, there’s no sign here of the gravitas that would distinguish Soto’s mature work, but the nascent professional is already evident. His placement is very secure and very beautiful. In motion, he’s not merely fluid but also extremely, if casually, graceful. His dancing is consistently soft and floating. On take-offs and landings, his feet seem to caress the floor. (After one lovely solo passage, his fellow students, breaking stage decorum, come out of character and applaud him.) He takes his acting responsibilities seriously and carries them out naturally, as if he’d discovered that Luke had a personality not too far from his own.

The gift for partnering is apparent, too, lacking only the fine-honed skills and increasingly sensitive intuition that experience would bring. Self-confident, Soto exudes a quiet assurance that, vis-à-vis his partner, he will be in the right place in the right way at the right time. Along with this technical aplomb, he displays an easy sympathy toward his lady (the 18-year-old Katrina Killian—tiny, light, and quick) as well as a devotion and respect that might well be termed chivalric. He knows how to frame her, creating an aura around her like a halo, and he knows how to get the hell out of her way. Close-up shots reveal his large, capable hands and strong back. When supported pirouettes are on the agenda, he’s an enabler first class. You can see how, even in these early days, he “roots” his partner, stabilizes her in her most precarious positions and dangerous moves. He’ll stand at a slight distance—waiting, alert, ready—and then simply move in and become her center.

It should be remembered that it was Martins himself who chose Soto to play Luke. Perhaps he recognized the similarity between them as dancers, both in the buoyant, cushioned solo work and the suave partnering. There’s little physical resemblance between them. Martins was tall, blond, Greek-god beautiful. Soto is of medium height, jet-haired and olive skinned, with an Aztec cast to his features. His build is undeniably stocky, with a larger head and shorter neck than classical ballet, obsessed with harmonious proportion, prefers for its princes. Soto’s distinctive anatomy would eventually add to his onstage presence not merely dignity but also intensity, enhancing a key aspect of his temperament—a darkness and ferocity that seized the viewer and refused to let him go.

Now Soto’s audience must let him go, with thanks.

For succinct bios of Jock Soto, along with lists of ballets created for him and the many other roles he danced with the New York City Ballet, use these links:

http://www.nycballet.com/about/print_sotobio.html

http://www.sab.org/faculty_soto.htm

Photo: Steven Caras: Jock Soto, rehearsing Peter Martins’s The Magic Flute for the School of American Ballet’s Annual Workshop Performances, 1981

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

ON WITH THE NEW!

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / April 26 – June 26, 2005

One way or another, gala programs must be striking. This season, the New York City Ballet’s boldly shunned both Balanchine and Robbins, the guys who give the company its raison d’être, for five new additions to its repertory—all choreographed by current members of the home team. Three of these pieces were duets that could be taken, obliquely, as windows on the state of dance today, at least on NYCB turf, and the state of love in these postmodern times.

Albert Evans’s Broken Promise, set to Matthew Fuerst’s Clarinet Quartet, lets you see what’s best about Ashley Bouder: the diminutive, taut body—fueled by extravagant but implacably controlled energy—creating sharp, intensely vivid images in the vast space of the State Theater stage. Her costume, by Carole Divet, suggests what keeps some observers (like me) hesitant about joining her growing fan club. It’s a sleeveless, backless, cleavage-baring white leotard gaudily studded with giant rhinestones, and it makes her look like a Russian gymnast who’s a sure bet for the gold. At first Stephen Hanna seems to be there only to support her when needed, conveniently disappearing when he’s not. Then he gets some of his own high-octane stuff, though it’s interrupted when she hurtles out of the wings to throw herself at him—literally. Their duets look like physical competitions, sometimes friendly, sometimes hostile, and when the last moves of the dance posit them as lovers bedding down, you’re startled to realize that all that previous athletic bravura must now be understood as foreplay. What this piece says about love is that the sedentary among us should hie ourselves to the gym, pronto, or we won’t stand a chance.

Benjamin Millepied’s Double Aria, first performed by his chamber group, Danses Concertantes, in 2003, takes its name from its music—Daniel Ott’s Double Aria for Violin Alone. (Choreographer and composer have collaborated several times and are now preparing a piece for the School of American Ballet’s annual showcase in June.) Double Aria puts the violinist (Timothy Fain) onstage so that he’s all the more a partner in the proceedings and, indeed, sometimes a soloist, as the dancers fade in and out of the picture. These dancers are an extravagantly (almost eccentrically) long-limbed pair, Maria Kowroski and Ask la Cour. We see them first, then again at intervals, in silhouette, a tactic that emphasizes their shape, as do the repeated vertical undulations and complex intertwinings Millepied assigns them. Kowroski is subjected by her partner to a certain amount of fling-and-drag—a tactic that has cropped up frequently in new pieces at NYCB. I suppose nothing personal is implied when the work purports to be abstract, though—you know how it is—some viewers might just take it personally. The structure of Double Aria wasn’t entirely clear to me, but, giving it the benefit of the doubt, and knowing that Millepied is French-born and French-trained, I thought that it might be one of those subtly clever schemes French intellectuals dream up. Waiting for the enlightenment that might come with a second viewing, I enjoyed the air the dance had of being a sketch spontaneously improvised to the seductive meandering of the music. What it tells us about love—or, at any rate, a “relationship”—is that it needn’t engage the soul.

Edwaard Liang’s Distant Cries, to a plangent Albinoni score, was first seen earlier this season in the repertoire of the chamber group Peter Boal & Company. Danced here, as it was there, by Boal and his frequent partner Wendy Whelan, it is tinged with the dancegoer’s knowledge that Boal will retire from performing in June and leave for the West Coast to direct Pacific Northwest Ballet. Liang’s choreography and Whelan’s increasingly sensitive interpretation of her role suggest themes of loss and grief. (The idea of something irreplaceable’s coming to an end is a particularly big deal at New York City Ballet, going straight back as it does to the death of Balanchine.) Liang uses his dancers wisely, capitalizing on Boal’s reticence and purity and Whelan’s ability to look utterly fragile and malleable without fully concealing a fascinating will of steel. The choreography, if not remarkably innovative, is reasonably adept and unaffected, marred only by some inexplicable peculiarities—suddenly flexed feet in an otherwise classical context and a repeated phrase for the arms that looks as if it should mean something, but doesn’t. What it tells us about love is that, no matter how devoted, it doesn’t last. Of the messages offered by the three duets, this is the only one to interest itself in tenderness.

Two offerings on the program, by the company’s most frequent providers, supplied some expansiveness to contrast with the restricted duet form. In his Tālā Giasma, set to the Estonian composer Pēteris Vasks’s Distant Light: Concerto for Violin and String Orchestra, Peter Martins returns to the concerns of his Eros Piano: A man—perhaps searching for an elusive ideal love, perhaps merely a passerby distracted in the humdrum course of his life—encounters more than one alluring but mysteriously remote lady and finds it impossible to opt for this one or that.

This time there are three women (Sofiane Sylve, Darci Kistler, and Miranda Weese), and they appear to be goddesses, or at least nymphs. Sheathed in palely tinted body stockings, they dance in Mark Stanley’s delicate dawn light. When the man (Jared Angle, replacing the injured Jock Soto) first comes upon them, they are a benign sisterhood, inclined to lyricism. Once he engages with them singly, their individual temperaments surface. Sylve becomes demonic, thrillingly so. Weese displays an implacable strength, but it is cool and remote, while Sylve’s vehemence is sensual. Kistler remains gentle and tender, almost pleading with the man to love her, rewarding him, when he responds, in dulcet terms agreeably tinged with pathos. The three come and go, with the man expressing his confusion (or is it frustrated longing? or dismay?) in solo passages, then masterminding a final quartet. Still he never arrives at a choice, and the ballet ends with him standing behind the women’s recumbent bodies, his arms raised toward the heavens.

The choreography makes much of the women’s extravagant extensions and some sudden, dramatic drops from a supported position on pointe to the floor, as if to claim that modern-dance turf for classical ballet, which traditionally adheres to an aristocratic verticality. Otherwise, it’s pretty much business as usual, including the quotes from Balanchine. Here they’re mostly from Apollo (about another fellow who comes upon a trio of lovelies) and are far too many and too literal, co-opting verbatim text only to sully it. It might also be observed that Balanchine has his hero make a clear selection among the three muses, so there can be a central duet that is key to the firm shape of the ballet. Martins’s piece seems too long, I think, because it is diffuse.

Tālā Giasma also connects, obviously, to Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un faune and, not so obviously, to Bournonville’s A Folk Tale, in which, long ago as a young principal with the Royal Danish Ballet, Martins played the hero, Junker Ove. On the surface the golden youth of everyone’s dreams, Ove is nonetheless a troubled soul, at odds with his destined bride—and rightly so; she turns out to be a troll. He eventually meets his proper match—all sweetness, light, and purity of heart—but not before he has been set upon by the supernatural Elf Maidens (cousins, you might say, of the wilis in Giselle) whose first appearance, rising from a trapdoor in a dense fog, is as a single woman who suddenly, terrifyingly, morphs into three. I’m not saying Martins was consciously thinking about A Folk Tale when he made Tālā Giasma; I’m saying that what one has seen and done remains irrevocably a part of one’s equipment.

Christopher Wheeldon’s An American in Paris, the only new piece on the program to boast décor and a sizeable cast, was no doubt an attempt to send ’em home entertained. Despite the blandishments of the Gershwin score, I slunk home depressed at the conspicuous emptiness of the dance and worried about the possibility that Susan’s Stroman’s Double Feature, which reportedly sold a good many NYCB tickets last year, might be evolving into a regularly used genre, in which a popular vintage movie is co-opted for vacuous shenanigans. Balanchine was no fool. He understood the need for a cheerful program closer. To fill this slot he created ballets like Western Symphony, which was colorful and lighthearted and—for people who cared about that sort of thing—had real choreography. Wheeldon’s effort has innumerable reference points, four drops by Adrienne Lobel ( faux-Cubist takes on tourists’ Paris—a Seine-side quay, the picturesque rooftops, et al.), and lots of pointless agitation.

Damian Woetzel, playing Gene Kelly, gets to mingle with the requisite generic types of Paris in the fifties: pert jeunes filles; young matrons in straw hats and gloves; anonymous guys in berets; a lady of the night; several gendarmes; a nun and her Madeleinesque charges (only three, so the “twelve little girls in two straight lines” effect was blown); and a cyclist (on his machine) taking a break, no doubt, from the Tour de France. He also gets to dance a bluesy duet with his sweetheart-in-pink (Jenifer Ringer, who curls around him like a kitten) and enjoy a little encounter on the side with an adorably saucy Carla Körbes, who emerges from a unisex gang of street toughs. None of this has any originality as dancing. And then we find out (surprise! surprise!) that it was all a dream. After raiding the film for a few basic situations—and failing to develop them—Wheeldon still counts on our transferring our nostalgic affection for the movie to his pallid show. Gimme a break!

Photo: Paul Kolnik: Jenifer Ringer and Damian Woetzel in Chrisopher Wheeldon’s An American in Paris

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Pam Tanowitz Dance

The choreography evolves from walking to whirling, from moves as plain as street signs to the complex body language of emotional enigmas. Village Voice 5/5/05

A PALPABLE HIT

Mark Morris Dance Group / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / April 19-23, 2005

This year, the Mark Morris Dance Group brought no brand-new, grand-slam work to its annual season at BAM. The sole novelty was a piece that had its premiere last fall, way west, in Berkeley, California. But it’s a honey. Rock of Ages, set to the adagio movement of Schubert’s Piano Trio in E flat, is a small, quiet dance that, like meditative deep breathing, expands the consciousness until it seems to reach the deepest feelings and an ever-widening understanding of how the world works.

Its population of four, plainly dressed, enters one by one from the four

Dominating the dance are brief phrases that, after their original impulse, slow and then coalesce into sculptural poses; these, having registered, melt into the succeeding phrase. Certain gestural motifs keep repeating as if they were lodestars. In one, the dancer turns her/his back to the audience, extends one leg behind herself diagonally and stretches her arms behind her back, hands clasped. She turns her head to one side, tipping it downward as if to examine the earth, then suddenly twists it to the other side, and upward, as if scanning the sky. (I thought of 9/11. How could you not?) Elsewhere, a single dancer faces the audience dead on, legs wide, knees deeply bent, arms extended horizontally, as if measuring the space or rooting herself to mark it as significant.

The dancers seem to traverse the stage at random (though even the most casual examination of the choreography reveals that their placing and timing are exquisitely plotted). Encountering one another, they don’t appear so much to be relating as singular personalities with private agendas as simply participating in the same event or sharing, almost anonymously, a common feeling. (Again I thought of 9/11. How could you not?) Occasionally they cluster–in pairs, occasional trios, even all four together, but only very briefly, for the stream of the dance is very fluid—then quickly regroup, exit, reappear. They look into the distance a lot, occasionally at each other, in a prevailing state of self-contained contemplation. Some swift and airborne things happen, too, but they’re just accents placed by a master well aware of the pitfalls of self-indulgence.

The whole dance emanates from the music as if Schubert’s sublime trio were—on this particular playing—being rendered as a quartet. The choreography has a calm, fated feeling; everything that happens is presented as acceptable and accepted, on a plane that lies beyond the tumult of contradiction. I wanted it to go on forever; when it was over, I wanted to see it again right away.

In the engagement’s four performances, eight dancers, ranging from veterans (among them, Joe Bowie, whom followers of the troupe love like family) to a relative newbie (the heavenly Rita Donahue), rotated in the four roles—in different combinations. Morris is the last choreographer on earth to consider his dancers interchangeable. But they are replaceable, instructively so. The shifting distribution of personnel—a tactic used in other parts of the repertory as well—shows any spectator on a repeat visit how a choreographic text, while remaining stable, is significantly inflected by the performing artists essential to bringing it to life.

This one-program engagement also boasted a burnished production of Morris’s 1995 Somebody’s Coming to See Me Tonight. Set to familiar songs by Stephen Foster, it illustrates Morris’s great gift for continually shifting tone within a single work, deepening the overall effect of the choreography by playing one mood against another or, more typically and wonderfully, intertwining them to reflect the way in which real life experience sends us multiple simultaneous messages. At the time of their composition (the mid-1840s to the mid-1860’s), Foster’s songs reflected prevailing sentiments in genteel American culture. Subsequently they came to be considered over- (even nauseatingly) sentimental. Nowadays they’re hailed as examples of classic Americana. Revealing the profound shadings that bodies can lend to words, Morris constructs scenes that find innocent tenderness in love and a final (even welcome) peace in death. Abutting or coexisting with these echt-Foster evocations are ironic takes on the lyrics that infuse them with bawdy humor or irrepressible gaiety (as in the polka that’s rendered in square-dance formations with an odd man out) and an underlying sense of life’s tragic dimension. Like almost all of Morris’s choreography, the piece is immaculately structured, with patterning at once surprising and satisfying in the way Balanchine’s is. The dancers, attentive to details of gesture and feeling, make it luminous.

The program was completed by Silhouettes, a disquisition on mirror-imaging, as well as From Old Seville, a riff on the excesses and beauties of flamenco style, which is too short, and Rhymes With Silver, a glorification of its Lou Harrison score, which is far too long. Seville featured Morris, who, though growing ever more portly as he winds down his performing career, is as rhythmically acute as ever, and Lauren Grant, a tiny, swift, well-muscled blonde, who refuses to be upstaged by the boss. Silver employed just about everyone but Morris, and, if there’s a grander heterogeneous troupe of dancers around, I’d like to know where it is.

Photo: Susana Millman: Michelle Yard and Craig Biesecker in Mark Morris’s Rock of Ages

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

New York City Ballet’s Sofiane Sylve

Sofiane Sylve’s sheer physical vitality feels like an engine that energizes the entire theater, filling it with joy. Village Voice 4/19/05

Peter Boal & Company; Paige Martin and Caitlin Cook

Retiring from the stage in June, Peter Boal, longtime New York City Ballet principal and a bastion of pure classical dancing, appeared with his chamber company for perhaps its final season. . . . Paige Martin and Caitlin Cook: A program curated by pomo dance celebrity Sarah Michelson should have been more striking. Village Voice 4/19/05