Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

When I titled my series of articles on the Royal Danish Ballet’s 3rd Bournonville Festival “Total Immersion,” I truly meant total. In the 13 pieces preceding this one, I aimed to concentrate on covering all the performances of the existing Bournonville ballets—which were, after all, the heart of the Festival—and what seemed to me the most compelling Bournonville-related exhibitions. But there was more, much more—some of it open to the public, some of it organized especially to familiarize foreign journalists and other interested parties with Bournonville’s world.

In addition to the exhibitions I’ve written about at length in the “Total Immersion” series, there were a few I didn’t have the time and strength to report on. These included Alt dandser, tro mit ord! (Everything dances—take my word for it!) at Thorvaldsens Museum, curated by the musicologist Ole Nørlyng. It explored the link between Bournonville and the neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), whose dulcet idealization of the human form greatly influenced the choreographer. The prolific research librarian Knud Arne Jürgensen produced yet another exhibition—this one at Bournonville’s home in Fredensborg, a suburb of Copenhagen favored by the Danish royal family—placing the choreographer in the circle of his family and in the wider but similarly intimate circle of his friends in the arts. And so on. I couldn’t help feeling it was a pity that the life of the exhibitions was almost as ephemeral as dancing. Still, as I’ve written, Digterens Teaterdrømme (The Poet’s Theater Dreams) is available in a splendid online version, while Tyl & Trikot, the imaginative display of costumes for the Bournonville ballets, has been extended until July 10 and is accompanied by a useful catalogue, available through the National Museum.

In addition to Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter’s six lecture-demonstrations on the Bournonville Schools—open to the public and a huge hit with the Festival audiences—there was an illuminating and vastly entertaining invitation-only program on mime, organized by the effervescent Dinna Bjørn. It explored—with piquant demonstrations—the connection between the mime in the Bournonville ballets and the mime used in the playlets given nightly at the Peacock Theatre in the pleasure gardens of Tivoli, the site of Europe’s longest unbroken tradition of commedia dell’ arte performance. Bjørn, who now heads the Finnish National Ballet, after a distinguished career as an RDB dancer, began her theater life as a diminutive devil in one of the Peacock Theatre pantomimes, when her father, Niels Bjørn Larsen, headed both the RDB and the Tivoli troupe. Bjørn’s program was given on the raked stage of the eighteenth-century Court Theatre, where Bournonville himself once danced, and which now houses the Theatre Museum, an enchantment in itself. On another day, journalists were treated to a full performance of a pantomime play at the Peacock Theatre and a tour of the minuscule backstage quarters where all the stage machinery, including the device that unfurls and retracts the peacock-tail curtain (it’s constructed like a fan), is worked by hand.

Other mini-excursions included a trip to Fredensborg to view Bournonville’s home (see above) and to visit the Bournonville family’s burial site in the Asminderod churchyard—all simplicity, greenery, and peace. There, according to Jewish custom, I lay a small stone on the grave markers of the master and his father, Antoine Bournonville, who headed the Royal Danish Ballet when his son was young and, presciently, took the boy to Paris, where he learned—and then co-opted—the French Romantic school of dancing.

The RDB company and school, which were operating behind firmly closed doors at the first Bournonville Festival in 1979 have adopted a new policy of openness in recent years, so journalists were allowed to observe a number of classes and rehearsals. Though I didn’t attend any this time, I’ve happily done so on earlier visits, since a behind-the-scenes view can provide piercing insights into what you see on stage. Last year, in these pages, I explored the issue of the extraordinarily high caliber of the RDB’s male dancers by looking into the training of the boys and young men in the company’s school. To read Ballet Boyz, Danish Style, go here.

The Festival also celebrated the recent or upcoming publication of a slew of Bournonville items. A complete list of them appears here. I’m looking forward to reading Bournonville’s travel letters to his wife, who stayed home with their six children while her husband spent half a year in France and Italy, though, as the inscription atop the Royal Theatre’s proscenium says, “ei blot til lyst” (not for pleasure alone); the choreographer’s observations and experiences abroad, we’re assured, became part of his ballets.

Throughout the Festival, hospitality, a Danish specialty, was lavished on the visiting journalists and, of course, their local colleagues. Each participant—and there were over one hundred of us—was greeted as if he or she were a combination of dignitary and close family friend. Each was presented with a sturdy slate gray carry-on discretely marked with the Royal Theatre logo (in a gold that managed not to glitter) and weighted with publications connected to Bournonville and the Festival, from books to pamphlets to detailed lists of enticing events. Every round of activity seemed to conclude with the provision of (at the very least) sandwiches and glasses of wine, and every professional need, from general information to Internet use, was answered, with infinite cordiality, by the Royal Theatre’s press department staff. After every performance, there was a reception, at which speeches, food, and drink flowed lavishly, and excitement at being part of a telling moment in dance history ran high. Most of us went home to terrifying amounts of work that had piled up in our absence. What we really needed, instead, was a week on a deserted beach where we could lie inert, staring at the sea and sky, letting memory sort out and store up our experiences.

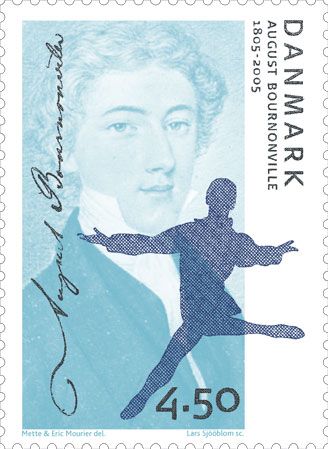

Photo: One of the two Danish postage stamps issued to commemorate the 200th anniversary of August Bournonville’s birth. The art is by Mette and Eric Mourier; the engraving, by Lars Sjööblom.

© 2005 Tobi Tobias