Savion Glover: Classical Savion / Joyce Theater / January 4-23 2005

Savion Glover is more than the greatest tap dancer of his generation. He’s a phenomenon–as a technician, an inventor, and a compelling presence. He’s been going from strength to strength since he was, at twelve, the tap dance kid. His latest project, Classical Savion, has him strutting his stuff to music by Vivaldi, Bach, Bartók, and Mendelssohn, with Astor Piazzolla thrown in for seasoning. Then, just in case you were missing tap’s more conventional accompaniment, Glover offers that as a finale, integrating the classical musicians–young, enthusiastic academy virtuosi led by Robert Sadin–into the suave proceedings of his familiar partners, The Otherz, a handful of jazzmen who couldn’t be more mellow.

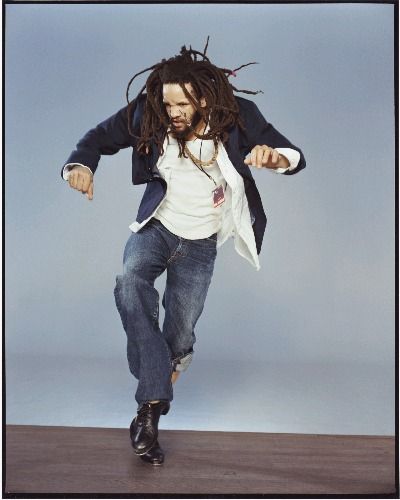

The stage provides Glover with a wide, miked wooden platform, the musicians ranged in curving tiers behind it, as if to hold the dancer in their embrace. Looking a decade younger than his 31 years, Glover enters wearing formal black evening jacket and trousers with a cantaloupe colored shirt (untucked, unbuttoned at the neck and cuffs) and a black bow tie (untied). The costume suggests a rebellious guy who’s fully aware of the grown-up dress code for concert performance and complies, all the while adamantly reasserting his own identity. His luxurious dreads are caught up in a low pony tail; he sports a beard that makes you think Abraham Lincoln.

In the course of what may be the longest vigorous solo stint in Western dance history, he’ll shed the jacket so that you can watch the shirt darken as it soaks up his sweat. In the course of the show, he’ll change the shirt a couple of times to a fresh one of a different hue, leaving the subsequent shirts open to reveal a white singlet, adding a bead necklace–all this a gradual return to the image of a slouchy street kid. Eventually he dances clutching his water bottle in one hand and, in the other, the black hand towel with which he mops his face. In the wake of his movement, the towel flares like a quietly menacing flag.

Like his costume, his stage demeanor slowly and inexorably reverts to a state that seems natural to his identity. Glover used to be a glum, deeply introverted performer. His refusal to make eye contact with his audience looked, to viewers expecting an ingratiating entertainer, both neurotic and hostile. He’s lightened up some in the last couple of years. He’s learned to smile, and his smile is delicious if still somewhat surreptitious. A quarter of the way through the program, though, he begins to lose his apparent resolve to look his public in the face. Performing to an excerpt from Bach’s Brandenburg concerti, he dances largely with his back to the audience, as if he were directing his efforts to the harpsichordist positioned upstage, or in profile, eyes averted from the house. Maybe it’s time, I’m thinking, to quit asking him for something different. The fierce inward focus of his dancing suggests that he’s delving deep into himself to reach something beyond himself, and it’s not our love he’s after but the achievement of ecstasy. Let him be; after all, he does take us along with him.

Now for what really counts–the dancing. Here’s what I notice most: energy (which seems to be part physical, part passion); control (tap is, among other things, a balancing act); a rhythmic acuity operating at genius level; a sly wit. Glover can, and often does, make a big ferocious sound, savage and blunt, the noise of a bad boy in the throes of a singularly destructive tantrum. At other loud moments he becomes a one-man artillery attack, all lethal precision. He juxtaposes his Orange Alert work with cascades of slow lustrous tapping (sensuousness in the abstract) or a tiny, quiet babble of taps that might come from small animals or even insects busily at work on a spring morning. Sometimes he rides the music; sometimes he becomes one of the instruments in the ensemble; sometimes he converts the score into a concerto in which he alternately plays solo and blends back seamlessly into the group.

He’s his own choreographer, of course, and his invention is wide-ranging and seemingly inexhaustible. I can’t count the number of things I hear (and see) Glover’s feet accomplish that I’ve never been privy to before. The improvisatory air of everything he does is invigorating, and the conversation his feet conduct with the floor is probably the most fascinating dialogue I’ll hear all year.

About the music: People have said even about works like Balanchine’s sublime Concerto Barocco, “Why would anyone add dance to music that is evidently complete in itself?” Glover has gone even further in annexing classical scores, not merely adding a visual dimension to an auditory one as ballet does, but adding a contrasting and possibility competing sound. And not in the gentlemanly fashion of Paul Draper, but in the style of a tough contender. Myself, I think it’s an interesting experiment, one worth continuing–to see how the odd coupling can be refined.

Meanwhile, Glover seems to have some notions about a rapprochement between classical and jazz music. In the closing segment of Classical Savion, he introduces the classical instrumentalists by name, one by one, and has each of them execute a bizarre little riff, as if to show that a musician from this camp can be a virtuoso and with-it at the same time. Then he summons the jazz band for the same exercise, lets it jam for a bit (lovely!), with the classical gang eventually invited to join in. Glover, feet still working, but only mildly, ends up center stage, facing the full ensemble, in the position of conductor. Admittedly, these goings on are disarming, but, apart from the jazz combo’s playing, they aren’t absolutely necessary.

My only other reservation about the program is that, except for a few phrases, it offers no opportunity to hear Glover dancing without music. Given the nature of tap, it can be accompanied perfectly by silence. But this is the most minor complaint, just a critic’s tic. In truth, I’m down-on-my-knees grateful for Glover’s dancing–in any fashion he chooses. Dancing like this is simply as good as it gets, and I consider myself wildly fortunate to be sharing time and place with such an artist.

Photo: Len Irish: Pre-classical Savion.

© 2005 Tobi Tobias