Slowly her fingers emerge from her shroud, their tips like tiny, vicious claws, her hands engendering subtle anatomical horrors that she places where her face should be. Village Voice 11/08/04

Archives for 2004

A FUGITIVE FRAGRANCE

American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / October 20 – November 7, 2004

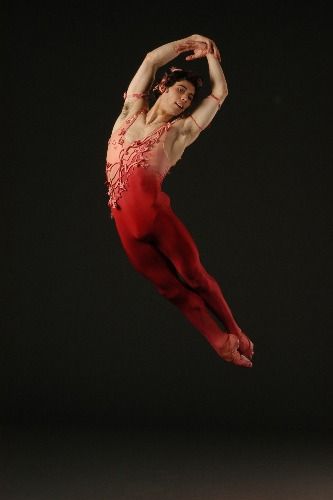

Le Spectre de la Rose is a nine-minute ballet choreographed by Michel Fokine in 1911 for Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina. It is set to Carl Maria von Weber’s Invitation to the Dance and based on a poem by Gautier that opens “I am the spirit of the rose / That you wore last night at the ball.” A young woman, having danced in society, comes home to her Biedermeier boudoir. The ecstatic dreams of young romance surround her like a perfume. She draws a full-blown rose from her décolletage and holds it to her face, absorbing its fragrance, then falls, languid, into her easy chair and drowses. A male spirit, costumed as the embodiment of the rose, leaps through her open French doors and dances—all voluptuous virtuosity. The incarnation of nature and its intransigent impulses, he induces the virginal dreamer to join him, then releases her to sleep and vanishes with a faun-like leap that, when Nijinsky performed it, made history.

Everything mitigates against American Ballet Theatre’s achieving a production of this piece that will be viable today, though it has, in Herman Cornejo, a dancer clearly born for the leading role. Our contemporary culture scorns the innocence and ecstatic vision of the subject. The lyrical dancing style Fokine requires in his neo-Romantic vein is almost a foreign language to dancers bred to thrill audiences with their dazzling technical accomplishment, not to beguile the public by means of subtle evocation. The combination of traditionally masculine and feminine elements in the main role makes a good chunk of the current audience uneasy, while an even larger chunk has trouble believing that anything created nearly a century ago can have the force, the significance, and the power to persuade the emotions as do the products of the present.

Everything mitigates against American Ballet Theatre’s achieving a production of this piece that will be viable today, though it has, in Herman Cornejo, a dancer clearly born for the leading role. Our contemporary culture scorns the innocence and ecstatic vision of the subject. The lyrical dancing style Fokine requires in his neo-Romantic vein is almost a foreign language to dancers bred to thrill audiences with their dazzling technical accomplishment, not to beguile the public by means of subtle evocation. The combination of traditionally masculine and feminine elements in the main role makes a good chunk of the current audience uneasy, while an even larger chunk has trouble believing that anything created nearly a century ago can have the force, the significance, and the power to persuade the emotions as do the products of the present.

At best, it would seem, the company can offer a viable reproduction—a dutiful, intelligent rendering that sacrifices inspiration to caution—just as it is doing this season with Fokine’s Les Sylphides. Even this—and it is no mean feat—is worth the effort. I think. Who knows? If the piece is kept active in the repertory, continuing performance might allow it to spring back to life and provide the kind of ecstasy for which we addicts used to flock to the ballet.

Postscript: At press time, ABT announced that it has slated a full program of Fokine ballets for its spring season at the Metropolitan Opera House, May 23 – July 16—the two mentioned here plus the tragic Petrouchka (created for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and, once upon a time, an ABT staple) as well as the lusty Polovtsian Dances from Borodin’s opera Prince Igor. This brave, admirable venture, clearly not driven by the commercial concerns that dominate arts management nowadays, looks like the impulse of an institution trying to retrieve its soul.

Photo credit: Marty Sohl: Herman Cornejo in Michel Fokine’s Le Spectre de la Rose

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

NOVELTY

American Ballet Theatre / City Center, NYC / October 20 – November 7, 2004

Trey McIntyre—born in Kansas and trained at the North Carolina School of the Arts—is better known in the West than here on the East Coast, primarily for dances he created for the Houston Ballet and Oregon Ballet Theatre. But his grasp of composition, thought to be unusual in a young choreographer (he began at the age of 20 and is still under 35), has earned him freelance commissions farther afield—from the New York City Ballet (a decade back, for its Diamond Project) to Germany’s Stuttgart Ballet.

Pretty Good Year, set to excerpts from a Dvorák trio for piano, violin, and cello, lives up to McIntyre’s reputation for a certain competence. A plotless work for three male-female couples and an odd man out, who is its star, or at least its driving force, it deploys its personnel deftly and confidently. It segues with ease from a single duet to simultaneous ones, then evolves into a trio, a quintet, and so on, with the extra man silkily woven in and out of the proceedings. Superbly danced by Herman Cornejo, who has an innate feral quality, the figure might be the nature god Pan, igniting the erotic instincts of the eternally youthful shepherds and shepherdesses in his pastoral domain. (Liz Prince’s charming balletic-bucolic costumes support the idea.)

The ballet’s opening section creates a good-humored atmosphere, one full of genuine sweetness, with the dancers going through their paces like children at play, all bounce and verve. Even this early on, though, the busyness of the choreography—a step for every note, it would seem; lifts that are too coyly devised; an almost complete absence of stillness—threatens to exhaust the spectator.

The adagio section that follows, though cannily constructed, is also marred by McIntyre’s hyperactive impulse; by his continuing to favor the curvy, buoyant moves of allegro dancing rather than switching to the more appropriate reaching, languid lines that make for poetry; and by a strange, seemingly arbitrary motif of small writhing gestures. Here, set against a colloquy for a pair of lovers (Zhong-Jing Fang and Bo Busby), the work for Cornejo expands handsomely in scope and dynamics, so that he seems to charge the space with unquenchable energy—until, inexplicably, he falters, to be gathered up in the other young man’s arms as if he were a flagging child succored by a tender parent.

By the time the dance moves on to a predictable jovial male-competition duet, the viewer him- or herself will be done in simply by the plethora of steps and the accompanying lack of information about the nature of the participants and their agenda. McIntyre makes suggestions, but they’re not powerful enough, and they fail to cohere. Pretty Good Year ends with the return of the three couples, more animated than ever, with Cornejo rushing about among them, seemingly egging them on, then falling flat on his back, spent. As climaxes go, it’s been done before—and more tellingly.

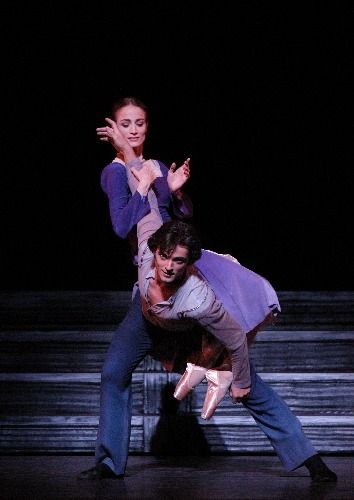

Wheeldon’s VIII investigates the critical moment in British history when—for reasons of lust, love, and a pressing need for a male heir—King Henry VIII forsakes his queen, Katherine of Aragon, for Anne Boleyn. After some juggling with the religious law of the land (not shown), Anne becomes the second of the notorious monarch’s six wives. However, like the pious, plaintive Katherine, the keen-witted, provocative Anne is unable to produce the required princeling, and so it’s off with her head and on to her successor, Jane Seymour, a delectable little thing who catches Henry’s eye just before the curtain falls.

Wheeldon has chosen not to make this vivid raw material an occasion for dancing, but Alexandra Ferri, who is celebrating her twentieth year with ABT, manages, through some quiet, intense acting, to portray a Katherine who is a vessel of mystery and grief. By similar means, Julie Kent creates an Anne whose intelligence, independence, cunning, and erotic appeal are almost palpable. Both portrayals create a definite character, and both have immense dignity. As their sometime husband, Angel Corella is miscast. He’s not effective as a sheer kingly presence and has been given no choreography that would show the mettle he’s revealed in dozens of other, widely varied roles.

Wheeldon, abetted by his choice of score, Benjamin Brittens’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, creates a somber mood that seems to repress dancing. The piece is governed by a formal severity that has the “ghosts” of Henry’s half-dozen wives haunting the premises. They are, indeed, striking. Rigged out in aristocratic Renaissance regalia (they don’t dance, so they can be laden with costume), they look like a gallery of Holbein portraits elongated to full-figure. But then the key duets, between Katherine and Henry as well as Anne and Henry, which should, logically, quicken the action of the piece and raise its emotional temperature, are hieratic and oddly unexpansive—even when the king first beds the seductive Boleyn—as if they were indicating situations and their accompanying emotions rather than enacting them. Wheeldon, who knows his craft, dutifully offsets this constriction and gravity with the rakish antics of a quartet of court entertainers, but then neglects to make the two modes of behavior inflect each other. The court—eight men and eight women strong—thrashes about busily and handsomely, but remains anonymous. Its members appear to have little relation to the principals and certainly no opinion about what’s going on, though you’d think their ranks would be rife with it. The only indication of the convoluted intrigues that must have been a part of Henry’s affairs is an ongoing motif of people watching each other from a distance in the ominous pervading gloom. Still, the act of watching, however potent a contribution it makes to the atmosphere of a dance, does nothing to enliven it in terms of motion.

As a whole, VIII has the air not of a dance or dance-drama but of a pageant. This is understandable given the fact that Wheeldon, though he has pursued his career in the States for the last decade (he is now Resident Choreographer with the New York City Ballet), comes to us from Britain, a land where the pageant genre has long flourished. Wheeldon’s origins also account for the fact that he may be rather more interested in Henry, Katherine, and Anne and their place in history than is your average American, despite his or her obsession with the misadventures of Prince Charles and Lady Di.

Next week I’ll report on ABT’s current renditions of two Fokine works, Les Sylphides and Le Spectre de la rose. Oldfangled though it may be of me, I’ve always had a penchant for yesteryear’s artifacts. In the case of dance, the most ephemeral of the arts, the survival of anything from the past in anything like its original form is little short of miraculous.

Photo credit: Marty Sohl: Julie Kent and Angel Corella in Christopher Wheeldon’s VIII.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

“Uqbartango”

Pablo Pugliese, born into a family of tango pros, entertains the notion that the soul of the genre can be expressed by augmenting its vocabulary with modern dance and ballet. Village Voice 10/19/04

“Mountain View Estates”

Kourtney Rutherford, whose résumé adds three years in construction work to familiar dance and drama credits, spins a goofy, macabre tale in a half-built tract house set. Village Voice 10/19/04

Octavia Cup Dance Theatre

Laura Ward’s new, ambitious, bilingually titled Enredaderas: Entanglemnts opts for excess at every turn. Village Voice 10/19/04

PULLING STRINGS

Basil Twist: Symphonie Fantastique / Dodger Stages, NYC / ongoing

Mark Dendy: choreography for Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / October 8, 11, 15, 18, and 21, 2004; April 5, 13, 16, 20, and 23, 2005

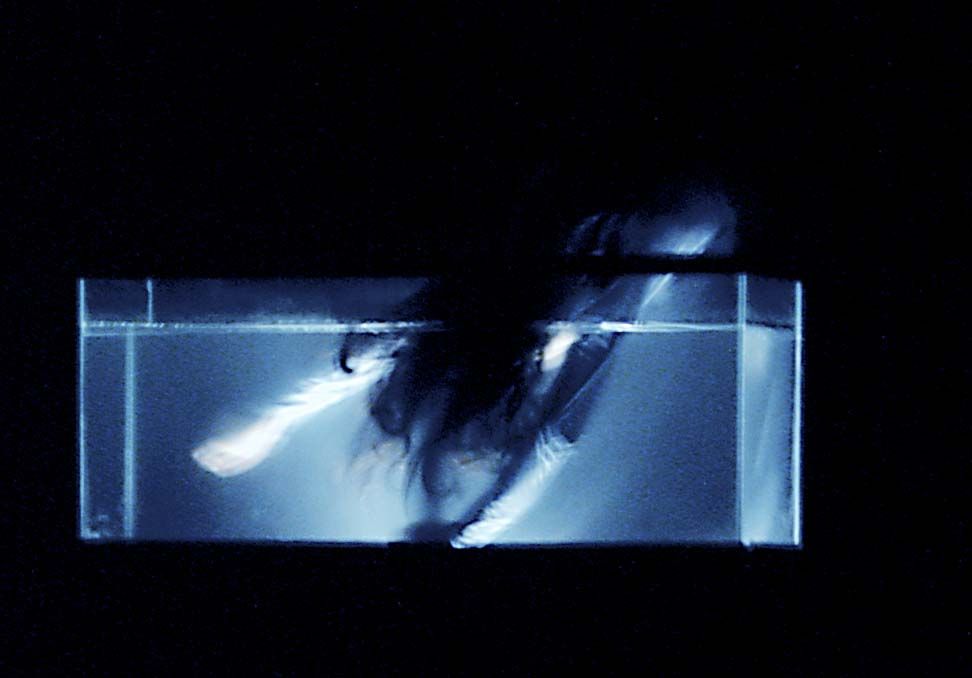

The idea of Basil Twist’s Symphonie Fantastique is magical: You’re sitting in this small neo-Bauhaus black-box theater—one of five spaces at the new, ingenious Dodger Stages complex on West 50th Street. And you’re staring in anticipation at an oversize fish tank or, if you will, a Lilliputian aquarium. Its contents are concealed for the moment by the sort of lavish looped red curtain (or is it a picture or projection of one?) typical of yesteryear’s opera houses.

Up the curtain goes to reveal water (defined by clusters of giddy air bubbles) and its inhabitants. You’ve been promised puppets, and marionetteers—six of them, including Twist, and two swings—are indeed listed in the house program with impressive credentials such as training at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts de la Marionette. You can even see a few of the strings and wires being used by the dexterous hidden manipulators. But this is no Punch and Judy, no Salzburg Marionette Theatre, no Muppets, no Bunraku. Twist is on the trail of abstract puppetry, and his “characters” are wisps of cloth, feathers, and tinsel strips.

The first puppet on is a smallish swath of white fabric that leads a turbulent life in its glassed-enclosed sea and seems to think it can fly as well. Watch it carefully. It will emerge as the show’s protagonist, a brave, optimistic little fellow with whom, I believe, the viewer is meant to identify. The personal-size sea will, accordingly, come to stand for the universe. For the sake of convenience, I’ll call our hero Salamander (Sal, on better acquaintance), since he often assumes the shape of one.

It turns out that Sal has a cluster of look-alike friends as well a capability to change color that gives him the air of a psychedelic chameleon. Alas, the trouble with Sal’s effects is that they could be rendered on video with no loss of impact or created electronically from scratch. I’m wondering if the several children in the audience recognize the difference between the live show they’re watching and the fare regularly served up to them on TV. I can see how the grown-ups might regard the performance as nothing more than a screen-saver with pretensions to Higher Things. Similarly, the intermittent bubble effects, though they have their charm, are duplicated and topped by many an exuberantly programmed public fountain, such as the one delighting and mesmerizing spectators ogling it from Greek-amphitheater bleachers at the newly constructed plaza fronting the Brooklyn Museum.

After running Sal through his repertoire, Twist introduces other players: feathery plumes (which shed a little, so that they enjoy an accidental afterlife) and other filaments, like thin, translucent ribbons. They’re ravishing, but by the time they’ve come and gone—certainly before they come again—the viewer may be admitting that it’s hard to engage with marionettes that don’t represent people or animals, if only in fantasy forms. Inanimate objects, animated though they may be by their keepers, are pretty much incapable of narrative and its offspring, drama—unless, of course, they’re anthropomorphized (as I’m guilty of doing, naming Sal). One-third of the way through the hour-long show, Twist’s material begins to look merely like eye candy, the idea of it far more compelling than the execution and the result.

No doubt Twist himself recognized the problem and, applying an obvious remedy, added the attention-getting element of apocalypse—or at least enough hints of it to keep his viewers alert. First he sets the scene, taking us to a midnight blue forest glowing with tiny specks of flickering light, as if it had been invaded by fireflies. Or is he, perhaps, showing us a single tree, bedecked with tinsel and inexplicably submerged in a dark lake? Beauty, mystery, and menace; the atmosphere serves as a prelude. From here on in, Twist counts heavily on the audience’s impulse to create story—and thus meaning—where none exists, at least at the literal level. The phenomenon is common. Most people can’t bear looking at things they can’t identify. Think of how often abstract painting, sculpture, and dance is greeted by a plaintive or hostile “What is it?”

Stubbornly enigmatic, Twist moves us to a shades-of-gray Nowheresville punctuated by hazy beams of light that suggest outer space and punches the action right up to Star Wars level. Small, brave Sal returns to thrash his way through the fuzzy, shifting crosshairs, attended in time by his loyal pals. The creature’s earlier idyll of indolent, graceful swimming that segues into ecstatic flight becomes a mere memory of calm before the storm. Swirling himself into a roll, Sal resembles an angry little cyclone. And now an ominous patch of inky threads invades the silvery space like a cancer, devouring or blotting out huge segments of the once-upon-a-time peaceable kingdom. Hope is not quite abandoned yet; the section concludes with the appearance of a portentous glowing speck surrounded by smoke, like a match ignited in darkness.

Next, a scene of vibrating cylinders. Remember Claes Oldenburg’s outsize soft sculptures of small, hard, everyday objects? Like that—if he’d done cigarettes. A pair of these flexible columns (in ironic pastel tints) invades the foreground from opposite sides like self-important opposing leaders, confronts but doesn’t take that fatal last step into combat. Each is then portentously seconded by a second. The threat comes to nothing. Generals and lieutenants retreat to their own sides only to repeat the inconclusive face-off. In the background, a close-packed line of them—let’s call them The People—trembles. It looks like politics as usual, but this stuff is punctuated by intermittent fires, green on one side, red on the other. And our innocent salamander beams straight into the conflagration and is destroyed.

And so it goes, the same basic elements used in increasingly agitated and elaborate ways, accompanied by Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, conveyed by a sound system evidently so primitive it has only two modes: OFF and VERY LOUD. I must say the music supports the visual antics, lending them a drama of danger, conflict, and bliss they might not otherwise convey so clearly.

Maybe it’s just me, subjected to too many excursions to the planetarium, first with small children my age, then with my own children, and then with my grands, but Twist’s show reminds me of those darkened-auditorium displays in which the nature of the universe is depicted in visuals that are essentially so abstract, I slip almost immediately into a stupor. Others have certainly reacted otherwise to Symphonie Fantastique. When the show was first done in 1998, it was all the rage with the downtown crowd and garnered both an Obie award and a Drama Desk nomination. And I haven’t given up on Twist. He’s preparing a new show, Dogugaeshi, based on esoteric Japanese puppetry traditions now threatened with extinction. Japan Society will present it November 18-23. Given my susceptibility to Japanese art and to puppetry, with its beguiling combination of the sophisticated and the ingenuous, it sounds like my kind of show.

The fall season in New York was full of puppet-driven productions, the most elaborate of them being the Metropolitan Opera’s new rendition of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute). Its mastermind was Julie Taymor—an opera director long before The Lion King made her name a household word—who was responsible for the overall concept, the costumes, and, with Michael Curry, the puppetry. Gregory Tsypin did the overbearing phantasmagoric sets. The puppet effects are a bit much, too. One patron hardly exaggerated when he claimed that the overload of visual stimuli prevented him from hearing the singing. Mark Dendy got the choreography credit. I’d be happy to follow the dictates of my job description and comment on his work—if only I could figure out what he did.

Nearly all of the movement interest belongs to the puppets, manipulated by an agile crew shrouded in black: an enormous dragon breathing fire (if not smoke) who nearly fells the princely hero, and requires at least ten deft attendants; a gaudy, avian flock fluttering on long willowy sticks to surround and tantalize the bird-catcher Papageno; a pack of polar bears (the best item in the show) that prove to be kites, inflating to full size and power as they’re guided aloft, cloth miraculously becoming flesh and muscle, then collapsing like melting marshmallow; and (unworthy of the occasion) a feast of flying food. Where did Dendy’s work come in? Was he responsible for the predictable patterns these objects create in the air? The delight, where it exists, lies in the objects themselves, not their traffic patterns. Presumably, Dendy choreographed the scene in which some absurdly long-legged birds, including several of the flamingo persuasion, offer a Vegas riff on Swan Lake, but this stuff is so routine, I wonder if some irony was intended, then only feebly resolved.

Throughout the production, the puppets, the costumes, and the sets conspire too blatantly to overwhelm the spectator. The puppet effects add to their sins by teetering on the edge of the Abyss of Cuteness, revealing a shameless cousinship with the world of Disney. As a dance critic, I found the most fascinating aspect of the evening to be the sight of human bodies going through pedestrian or theatrically stylized movements with only minimal visceral impulse and fluency, performing rote gestures while—as if emanating from another body entirely—the voice spoke worlds, rendering every idea radiant with feeling.

Photo credit: Carol Rosegg: Basil Twist’s Symphonie Fantastique

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Dancenow/NYC

ELEMENTS OF STYLE

Johannes Wieland / Diane von Furstenberg the Theatre, NYC / October 7-10, 2004

Johannes Wieland opened his recent concert with his 2002 Parietal Region, which, for the uninitiated, might serve neatly as Wieland 101. As this piece reveals, the choreographer, whose stern aesthetic may be related to the Bauhaus movement in his native Germany, favors austere architectural settings and groupings, along with a parallel emotional reticence.

Frederica Nascimento’s set for the piece features six austerely white boxes, two of which, with transparent “windows,” serve as cages—and, secondarily, jungle gyms—for a quintet of dancers (Julian Barnett, Brittany Beyer-Schubert, Nicholas Duran, Eliza Littrell, and Isadora Wolfe). In this bleak, handsome landscape, different but related activities occur simultaneously in various locations. Each of them is interesting on its own, while the stage picture as a whole is visually coherent, and, in that sense, meaningful. Here, as in his other works, Wieland proves himself to be more of a visual choreographer than a visceral one.

Needless to say, the set dehumanizes the dancers. The main box makes you think of a living-room aquarium, its confined denizens entirely at the mercy of random gazing eyes. When an inhabitant stands erect in the structure, the top of the frame cuts his head off from view. That overhead frame also conceals the equivalent of a chinning bar. Dancers inside the box hang from it at intervals. One woman swings from it upended, like a body taken from the gallows and hung to blow in the wind for passersby to notice, if they will.

The piece is handsome and ruthless—and part of its ferocity comes from the fact that both dancers and choreography do their best to seem affectless. But Wieland has another card up his sleeve. His dancers, who move with the sudden, lethal action of switchblades, are also extremely sensuous. Behind their lack of overt expression lies a potent universe of moods. Most of the feeling suggested is typical of our times—cool, subliminally hostile, and despairing. Nevertheless, it is there, working on the spectator’s emotions.

Parietal Region is clearly the ancestor of the new Corrosion, whose six dancers (the above, plus Branislav Henselmann) dwell in a recognizable contemporary world where love seems impossible. In changing-partners couples, they manipulate each others’ bodies, all the while apparently incapable of—perhaps immune to—effective communication. They seem more aware of invisible observers than they are of each other. An embrace is anatomized in slow motion; rites that should pass for intimate are performed eyeing the audience, as if gauging the anonymous public response. The prevailing climate is one of imminent disaster, though the piece never offers the catharsis of actual calamity. Just about every moment in it would make (does make) a still photo worthy of the high-end glossies.

Espen Sommer Eide provided the atmospheric electronic music for Corrosion, manipulating his equipment onstage. Diane von Furstenberg, who provided the theater for the concert—it’s part of her atelier, in the Manhattan’s fashionable Meatpacking District—designed the costumes. Much to her credit, the pearly gray outfits are suitably draped for the action of highly flexible, highly articulate bodies. The women’s dresses, translucent over their breasts, with skirts that cling to the hips, then flare out in clusters of pleats, make their wearers look like latter-day goddesses. The charm of both the men’s and the women’s outfits lies in the fact that they could be worn on the street in that downtown locale, where trendy restaurants and boutiques indicating fashion’s future spring up amid the persistent odor of dried blood.

The program included a newish trio, One, seemingly a three-ages-of-man affair. It’s full of Wieland trademarks, but vague in both its matter and meaning. Still, it was performed with distinction by two dance-world “elders”—the 65-year-old Gus Solomons jr, who, with one of the greatest mature faces in contemporary dance, brought to it a near-tragic dignity, and Keith Sabado, who, at 50, continues to be a paragon of delicate precision. Wieland himself—35, but an old soul—offered little more than physical fluidity coupled with a reservation so adamant, he seemed to be avoiding the audience’s scrutiny. I suppose this, in itself, is an artistic statement of sorts.

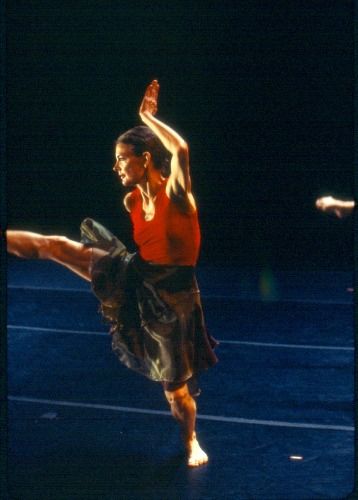

For me, the only dance on the program with more than visual or cerebral impact was the 2000 Tomorrow, named for and accompanied by the Richard Strauss song “Morgen!” (recorded by Jessye Norman) as well as passages of silence. Its “set” consists of three boxes, placed upstage, that are real aquariums. A trio of dancers (Barnett, Beyer-Schubert, and Littrell) lean over them to immerse their heads in the water for just a little longer than is comfortable to watch (and, no doubt, to do), then emerge from this near-death experience to splash the air and floor with giant droplets in wave-like arcs.

Though the dance then moves away from the tanks, it keeps returning to them. They are both objects and places, and they constitute the core of the piece. One of the women dips her brow and arm into the water in a singularly lovely gesture that might belong to a religious ritual. It suggests baptism, or a plea for—and gracious granting of—absolution. In a more violent (and typical) passage, the other woman (I think it is) holds the man’s head under water. This act—essentially inscrutable, as is much of what happens on Wieland’s stage—seems to lie somewhere between childish prank and erotically tinged cruelty. Later, the man, as if losing control, flings himself upon a tank and savagely strikes the surface of the water. The sound created by the impact is more terrifying than gunfire.

In between the encounters with the water there is much terrestrial thrashing about, much of it with the dancers sitting, lying, and rolling on the floor. More specific images of combat between an erect pair are witnessed by the third figure, whose arms and head hang limp, the very image of a person defeated by an environment that’s both hostile and hopeless and offers no viable alternatives.

The dancers wear silvery costumes by Stefanie Krimmel that might have been fashioned for postmodern garage attendants, and these designs are as integral to the piece as might be imagined.

I thought the whole business was fascinating and beautiful. It sold me, once again, on the idea that Wieland is a substantial talent. I wonder when—indeed, if—he’s going to unlock the box in which he’s confined himself among his personal obsessions.

Photo credit: Sebastian Lemm: Johannes Wieland’s Tomorrow

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

BODY LANGUAGE

Molissa Fenley and Dancers / The Kitchen, NYC / September 29 – October 9, 2004

More than a quarter-century after Molissa Fenley first appeared on the postmodern dance scene, an oddity in her way of moving—apparent throughout the cycles of solos and group works she’s choreographed—remains a distinct personal signature. She holds her hands sharply angled at the wrist, palms very flat, fingers tight together, thumb joined to them or splayed outward. This articulation, at once awkward and graceful, is accompanied by an unusual fluidity in the arms and a sentient pitch to her torso. It gives her a feral air, which is augmented by her intent concentration. She has passed this creature-like stance on—as far as any individual way of moving can be replicated—to the five women, at least a generation her junior, who joined her to perform some of her new and recent choreography in the first of two programs at the Kitchen. (The second, to run October 6-9, constitutes a revival of her 1983 Hemispheres.)

The look I’ve described proved to be most effective in the atmospheric sextet Kuro Shio, created in 2003. Set to music by Bun-Ching Lam called Like Water, this dance does, indeed, suggest an imagined natural world. The creatures disporting themselves in Evan Ayotte’s soft silvery jeans and translucent shimmering tops under David Moodey’s low, azure-filtered light might well be postmodern neriads. And while they are happily diverse in ethnicity, coloring, and body type, the dancers (Ashley Brunning, Tessa Chandler, Wanjiru Kamuyu, Cassie Mey, and Pan Tanjuaquio) are all clearly disciples of Fenley, who works among them, serving as the model for their inner-directed focus; their poised, unemphatic reiteration of gestures and groupings; the hieroglyphic work of their hands and arms.

The new piece, Lava Field, to John Bischoff’s Piano 7hz, is not as successful. It delivers a familiar Fenley message about the certain, if essentially unfathomable, connection among living things. In a kind of prelude, three women gently fit their bodies together. Lying on the ground, they move with the fluidity of molten lava—pouring in streams and coalescing in rivulets—as if they represented an ocean born of fire now lapsing into quiescence. When they’re erect, forming abstract stage patterns that allow them to disperse only to re-bond as parts of a matrix, the same principle holds. The implication is that interdependence, observable throughout inanimate nature, is no less present in human relationships.

The problem is that this is not exactly news and, in Lava Field, Fenley gives it no particular illumination or even intensity of statement.

Throughout the piece, the movement is very arm-y and leggy, as is this choreographer’s wont. Here you begin to wish—at least I did—that she would allow the mid-section of the body to take charge more, serve as an energy center, initiating the impulse for the dance and provide a compelling urgency in place of a calm that is neither hypnotic nor ecstatic but, rather, flaccid and monotonous.

From the first, I think, Fenley’s choreography has suffered from a condition that plagues all of modern dance—the limitations of a vocabulary derived largely from a single body’s instincts. It’s instructive to study how and to what degree some of the greats in the field—Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Mark Morris—have escaped from the prison of self.

Photo credit: Paula Court: Molissa Fenley in her Lava Field.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias