Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Heisei Nakamura-Za / Damrosch Park, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 17-25, 2004

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

In one, a sympathetic woman volunteers to serve as caretaker to the princeling who is hiding out for reasons too convoluted to record here. An objection arises: What if this woman’s youth and beauty should tempt the young man to sexual imprudence? (In truth, the lady in question is not so much nubile as the picture of matronly elegance, her bulky figure clad in a black kimono elegantly offset by touches of sienna and red, her soft, plump fingers manipulating a matching lacquered parasol—but we theatergoers know how to suspend our disbelief.) With furrowed brow and a sorrowful twist to her mouth, the woman ponders the problem. Then, seizing a taper from the burning brazier at her side, she heroically it presses to her cheek. When she removes it, the smooth white flesh is marred with a bloody wound. (The audience knows this is just a make-up trick, but gasps in horror anyway, because the performer makes the moment thrill with reality.) Her hands, all delicate agitation at the wrists, flutter with tremors of pain as she holds a cloth to the crimson streak. Offered a hand mirror, she confronts her scarred image, and now her whole body pulses with shock. Her face twists in her first voiced response to the event as if the burn had not merely ruined the outer layer of skin but also reached deep into muscle. “The face her parents gave her,” she declares, is now scarred for life, and she wants the onstage witnesses to know how much that disfigurement means to her. So, after the self-mutilating action that’s sensational in its brutality and courage plus the exquisitely calibrated physical detail of its aftermath, we paying voyeurs get to savor the irony of her verbally requesting understanding from her fellow characters in the play when she has already secured our empathy through the emotional intensity of her actions. From this scene, too, comes the telling line, “There’s no sense in matters of the heart, and the unexpected can always happen.”

Another, more extended passage, works as the centerpiece of the play. Danshichi, the tale’s chief character, quick to use force as reason, confronts his father-in-law, Giheiji, a low-life whose corruption is symbolized by his wizened body, filthy ragged clothes, and truly deplorable teeth. No paragon of everyday honor himself, Danshichi uses a fake bribe to make Giheiji right the most urgent of his numerous wrongs. Once Giheiji realizes he’s been duped, he heaps a torrent of abuse (some of it frankly scatological) on his son-in-law, taunting Danshichi into attacking him physically, reminding him all the while that the punishment for killing a parent is death.

Slowly the scene slips from rough comedy to a moral and emotional seriousness that belongs to poetry. And in the course of this progression, the scene, which can be imagined to have started at sundown, slowly darkens into night. The traditional black-veiled stagehands of Japanese theater move in with translucent lanterns extended on long poles, following the swiftly moving protagonists to illuminate their bodies and faces.

The ensuing battle—a tour de force blending sword swipes, body-to-body grappling, and profound psychological conflict that prefigures Macbeth’s—is so protracted it becomes hallucinatory. Danshichi, who has on his side a brute physical advantage and the single available weapon, is reluctant to commit a murder he’s sure both the law and the heavens will curse. More and more blood flows. The combatants’ clothing is gradually stripped away, and their hair hangs wild. The illumination grows increasingly fugitive, sometimes reduced to a single beam held up to a single crazed face. Eventually it becomes so dim that the frenzied action takes on the insubstantial air of a dream, then plunges into “endless night.” In the obscurity, the skeletal old man falls into a pool of muddy water and rises from it a dripping brown specter—not yet dead but already a ghost. Now, finally, Danshichi summons the courage (or desperation) to put his victim down forever and poses, briefly floodlit, a victor himself in extremis, passing his sword through a lantern’s flame, hysterically sloshing himself with buckets of water, as if, with these rituals, he might repossess his soul.

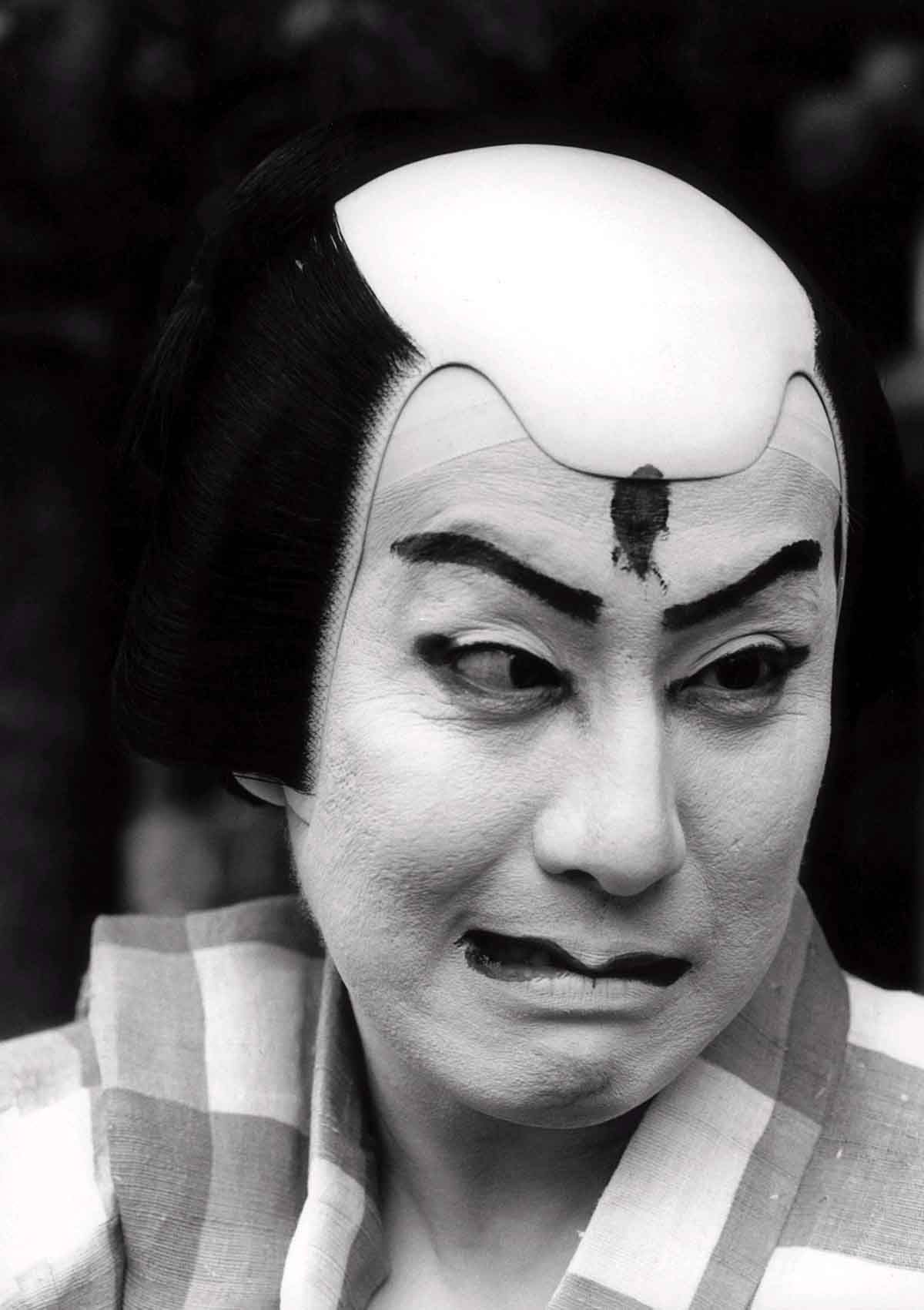

Have I neglected to mention that the self-sacrificing woman and the guilt-ridden warrior were played by the same actor? He’s Nakamura Kankuro V, a 48-year-old scion of a family that has been practicing the art of Kabuki since the 17th century. He does honor to his heritage.

Photo: Nakamura Kankuro V in Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka)

© 2004 Tobi Tobias