Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

The first week of the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration brought the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago back to New York after a 10-year absence. The company, which used to be resident here, was very welcome. In the old days, even when you weren’t feeling much admiration for it, you often still felt affection for the engaging personalities of its dancers and the troupe’s overall feisty spirit. To be sure, purists in the audience back then would complain about the Joffrey’s imperfect classical technique and the many pop numbers in its repertory (a majority of them by the company’s present artistic director, Gerald Arpino), but they were the first to be grateful for the late Robert Joffrey’s reaching out to choreographers outside the classical domain, such as Twyla Tharp and Laura Dean; his resurrecting “lost” but worthy ballets of the Diaghilev era; and his giving a major American presence to the works of Frederick Ashton. My own happy acquaintance with several Ashton ballets comes solely from their Joffrey Ballet productions. Looking at Les Patineurs, A Wedding Bouquet, and Monotones I and II this past week, I could only wonder, What happened? Not one of the stagings was as good as it should be—and had been.

Les Patineurs, choreographed in 1937 to ebullient music from Meyerbeer, pretends to chart the ups and downs of a winter’s eve Victorian ice-skating party. It has the all the requisite guests: A small spirited ensemble to demonstrate the peculiar pleasure of gliding, especially in tandem, and to react to spills with equanimity. Virtuosi in the form of a young man who’s a veritable whirligig and two sturdy young women who engage in a can-you-top-this? orgy of single-legged turns on pointe. A pair of lovers whose romantic accord is celebrated by a dulcet pas deux. Their locale, the set originally designed for the ballet by William Chappell—all white latticework trellises and hanging paper lanterns—has the charm of a vintage Christmas card.

While the choreography is quietly ingenious enough to fascinate aficionados, Les Patineurs is perhaps the most easily accessible of Ashton’s top-drawer works. Children adore it; people happy to know nothing about ballet succumb to it. But, though it requires of its performers nothing like the subtlety of emotion that must be understood and projected in, say, Enigma Variations, it does demand a secure technique—fluent and graceful in the upper body, covertly powerful in the pelvis and legs, crisp and delicate in the feet. This the present dancers of the Joffrey can’t quite muster. Or let’s say that some of them manage it some of the time, but that this proves insufficient to the occasion. Their vivacity is unquestioned, but it can’t conceal uncertain placement, flaccid footwork, tentative balances, or underpowered action in the thighs, which should be the base of a classical dancer’s turned-out posture.

The present look of the Joffrey’s Patineurs also suggests that there’s no one available to preserve the nuances of shape, rhythm, and tone that are significant in all dancing but absolutely an elemental concern in dancing Ashton. This flaw gravely undermines the company’s production of the 1937 A Wedding Bouquet, a far more sophisticated piece.

David Vaughan, in his Frederick Ashton and His Ballets, tells us what we need to know up front about A Wedding Bouquet: “It is not a narrative ballet, but rather a series of incidents at a provincial wedding in France around the turn of the century, one of those ghastly occasions where everything goes wrong.” The fragments of slyly near-nonsensical text spoken from the stage by a debonair narrator in evening clothes are taken from Gertrude Stein’s play They Must. Be Wedded. To Their Wife. The score, as well as the costumes and set, are from the hand of Lord Berners, who made a career of poetic eccentricity. And Ashton, with his magical fusion of fantasy and craft, gives a bizarre logic to the characters (Julia, for example, who “is known as forlorn”) and their often unfortunate interconnections (“they incline to oblige only one when they stare”; “they all speak as if they expected him not to be charming”), which only the literal-minded would question. But the whole business—sophisticated and amusing—has the fragility of a bubble; if not treated deftly and lightly, it breaks. I recall being enchanted, years back, by the Joffrey’s production. Now, with neither the dancing nor the characters fine-tuned, the piece is apt to appear incomprehensible or pointless to neophyte viewers and sadly coarsened to veteran fans.

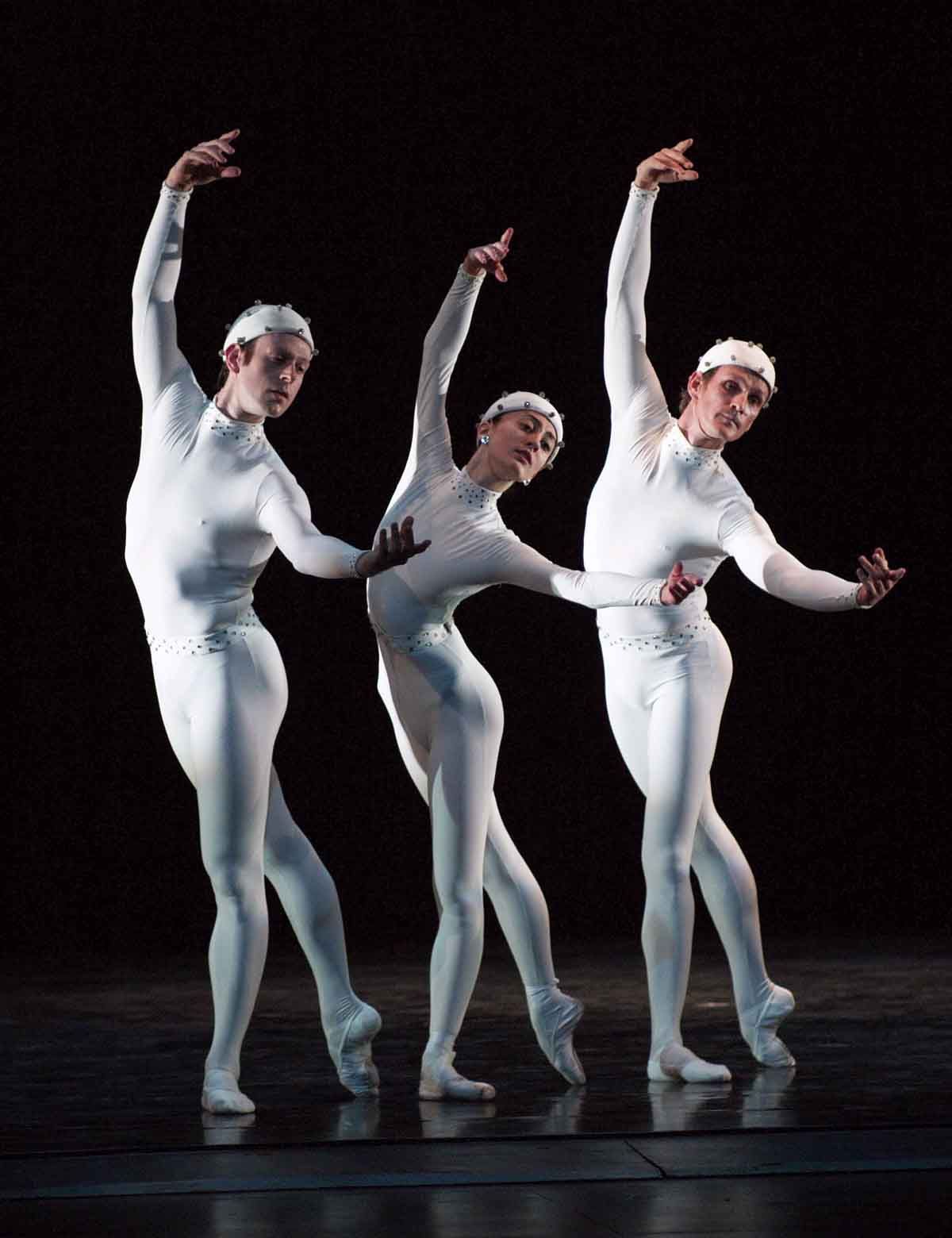

Monotones, the most important of the Ashton works the Joffrey presented, managed to survive a less than perfect treatment. It suffered most from the dancers’ technical inadequacies, but you could still see clearly what kind of ballet it is—celestial. It comprises two trios, now called Monotones I (set to Satie’s Trois Gnossiennes) and Monotones II (set to the composer’s Trois Gymnopédies). Monotones II, for two men and an extremely pliable woman, was choreographed first, in 1965, for a charity gala; Monotones I, for two women and a man, the next year, the earlier piece having been recognized as a miniature masterpiece. Most observers agree that Monotones II (which is occasionally performed separately) is the more sublime of the pair, but the two together are better than either one alone because of the sorcerer’s-mirror way in which they reflect each other in personnel, sculptural shapes, and spatial arrangements.

In each, the dancers are sheathed androgynously in pale skin-tight casings and helmets, here and there highlighted by brilliants, that give them the look of imaginary intergalactic travelers, voyagers to infinity. Their aloof demeanor suggests the divine remoteness and calm of a Buddah. Their dancing, spare to the point of austerity, seems to be a paradigm of purity—or of the very basics of classicism—an illusion that is only enhanced by its being inflected occasionally with eerie acrobatic configurations. It unwinds with hypnotic serenity, and each trio in its entirety, though it looks complete and self-contained, also suggests that it is part of a continuum lying beyond the grasp of mere mortals. The poses of the individual bodies and the ways in which they are grouped—actually touching, separated only by inches, or with generous space between them but still intimately connected visually—is intensely sculptural. At the same time, Ashton seems to be occupied with exquisite linear tracing. “The continuity of his line,” Arlene Croce wrote, “is like that of a master draftsman whose pen never leaves the paper.”

At an ideal performance, Montones doesn’t seem so much choreographed and danced as it appears to be an astonishing glimpse into the workings of the heavens. True, the center did not hold in the recent performances, but it looked as if the dancers and their coaches understood and honored the nature of the ballet and were attempting to do it justice.

Under Robert Joffrey’s leadership the Joffrey company annexed such a goodly number of Ashton works and presented them so gratifyingly that I, for one, would contend that it made a promise to its audience, a promise I ardently hope it will go about keeping.

Note: Having mentioned David Vaughan’s Frederick Ashton and His Ballets (Knopf, 1977) in all my postings to date on the Ashton Celebration—because I’m forever consulting it—I feel obliged to say that another ambitious Ashton tome exists: Julie Kavanagh’s Secret Muses (Pantheon, 1996). It contains some useful information, to be sure. However, it is maddening to read if it’s Ashton’s ballets you want to know about. It continually insists upon sliding without warning from the subject of Ashton’s work to his private life, which—unlike his art, in no way unique—is made to appear by turns seamy, frustrated, and pathetic, a fitting subject for a Boris Eifman. I’ve nicknamed Kavanagh’s book “Sir Fred in Bed.” I think of Vaughan’s book as “the Bible.”

Photo credit: Herbert Migdoll: Members of the Joffrey Ballet in Frederick Ashton’s Monotones II

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Correction: In my July 7 posting, Ashton Celebration #1, I recommended standing room tickets as a budget-conscious way of seeing the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration, currently at the Metropolitan Opera House. (Standing room tickets for American Ballet Theatre’s recent season at the Met cost $20; the advertised price range for Ashton Celebration tickets is $150 – $35.) A reader has since alerted me to the fact that standing room has not been made available for the Ashton Celebration. Representatives of the LCF tell me that (1) students of any age with a valid current student i.d. card can buy a single or a pair of tickets in the Family Circle at $20 per ticket, applying for them in person at the Met box office, and that (2) the Playbill Club \http://www.playbill.com/index.php\ is offering moderately reduced prices on $50 and $35 tickets.