All four choreographers—Janis Brenner, Susan Marshall, Ronald K. Brown, and Robert Battle—displayed an astute understanding of the newcomers’ formidable gifts and limited experience plus well-nigh palpable affection and respect for the rising generation. Village Voice 12/20/04

Archives for 2004

Himiko Minato & Dancers

A tense, haunted figure, Minato plays a tormented pilgrim in a dark forest, involved with lethal human threats as well as a portentously symbolic rope hanging from above. Village Voice 12/20/04

OUT OF THE ORDINARY

Merce Cunningham Dance Company / Joyce Theater, NYC / December 14 – 19, 2004

“Presented without intermission, each Event consists of complete dances, excerpts of dances from the repertory, and often new sequences arranged for the particular performance and place, with the possibility of several separate activities happening at the same time—to allow not so much an evening of dances as the experience of dance.”

The shortest and best way to describe a Merce Cunningham Event is in the choreographer’s own words. A series of eight Events took place at the Joyce just as the town was launching into full-blown winter solstice hysteria. In the company of the wealthy intelligentsia and a cluster of my colleagues, I saw the gala opening night performance on December 14. Baffling though Cunningham’s work can be, it seemed to me, once again, luminous in its perception, invention, and sophistication.

Here are some random notes. (I assume that, under the circumstances, a kaleidoscope of fragments is in order.)

The dancers’ appearances and disappearances—the famous Cunningham flock-of-birds effect—feel swifter and lighter than ever. Blink and you’ve missed one. In flight, the bodies look weightless, though never flat. Grounded, they combine oak-tree sturdiness with filigreed delicacy.

Suddenly, fearlessly, the figures plunge off the vertical into pitched arabesques or deep supported leans that suggest putting one’s whole being—soul as well as body—into a partner’s hands. Or, perhaps, self-immolation.

It seems to me that watching Cunningham is like taking a nature walk. The shifting landscape you scan offers many beautiful (or fascinating or eerie) things, but in an entirely evenhanded way. It is your own wandering view, guided by your own temperament, that selects which of them to notice, which of them to enhance through deeper contemplation, which of them to elaborate with your personal fantasies. The choreographer has chosen to abstain from dictating in these matters. He is present in the scheme, absolutely, but mysterious and silent.

A man stretched out at length on the ground slowly rolls over, wrapped in his own arms. His body seems as heavy as stone. Nothing leads up to this. Nothing leads away from it. It just happens.

Much Cunningham dancing looks like a distant branch of classical ballet. Evidence: the poised carriage of the body; the long, harmonious line; the insistently pointed feet; the attention paid to equilibrium; the unfailing composure and control; the idea that grace lies in harmony. And yet contradictory evidence exists everywhere. It’s as if the ancestors of what we see today at ABT or the Kirov and what we see at a Cunningham concert had once shared a dance continent subsequently split in two by a geologic cataclysm, the separated halves then evolving alone. Of course pedestrian vocabulary and animal motion play key parts in Cunningham’s dance language, too, and he has never forgotten entirely the fact that he was once a key performer with Martha Graham.

People frequently talk about the bird imagery in Cunningham’s work, and then the animal imagery—gazelles and suchlike loping across the plains—but you don’t hear so much about the sheer weirdness of the stuff that conjures up distinctly human encounters and endeavors: People flinging themselves about, all the while maintaining careful control. Bodies folding and twisting into impossible postures. Peculiar cantileverings and oddities of balance. Phrases that would pass as perfectly conventional dancing if the performer weren’t traveling backwards.

In these cases, the operation of the body may follow anatomical logic or just as easily contradict it—often in the space of a single phrase. Figures cooperate with each other or, just as often, confront or thwart each other’s expectations. Either way, there is no reference to an accepted norm of behavior. This is a society in which all the usual givens exist only to be skewed—and yet it’s incontrovertibly human. Cunningham, via his deft dancers, provides the text of the action. The viewer provides the subtext, and it is, invariably, a very strange one indeed.

Cunningham’s work contains many moments of stasis in which the dancer appears to continue traveling or gesturing in his own imagination.

Because Cunningham choreography firmly closes the door to melodrama (even conventional drama, to say nothing of characters or personalities ), it has a certain evenness of tone. Everything is set forth with the same elegance and equanimity. Some spectators find this excruciatingly boring.

Often, in Cunningham’s work, people fall to the ground, suddenly, and are quickly resurrected. I’ve often wondered what’s behind this recurring image—the falling into stillness succeeded by a rising back into action. Is it a metaphor for the nature of dancing? I know Cunningham would say—at the age of 85, he must be so tired of saying it, with that dogged patience of his that is nothing if not heroic—that it is not a metaphor for anything; it just is.

What delights me most about this choreography, and keeps me going when my patience with it flags, is its intelligence. It makes much of the other choreography I look at, whatever visceral or emotional thrills it may provide, seem stupid.

Often the performers display the antic beauty of traditional circus performers. They are extraordinary in their fleetness, their strength; their acuity, their devotion. Here are their names: Cédric Andrieux, Johan Bokaer, Lisa Boudreau, Julie Cunningham, Holley Farmer, Jennifer Goggans, Rashaun Mitchell, Koji Mizuta, Marcie Munnerlyn, Daniel Roberts, Daniel Squire, Jeannie Steele, Robert Swinston, Andrea Weber.

Jackie Monnier’s décor for the December 14 Event suggested—appropriately for the season—a winter carnival in the sky, and the program ended with some ebullient group shenanigans that brought to mind a Mexican fiesta. I couldn’t resist asking a Cunningham expert and devotee, where this last material came from, and she told me (Squaregame, 1976). Still, one of the most futile things one can do at an Event—and dance critics, being veteran Merce watchers, are most prone to it—is to rack one’s brains trying to identify the choreographic shards, put them back in their repertory context. It’s a fine parlor game, I suppose, but a profitless distraction from the business of seeing and the business, central to Cunningham’s Zen-infused aesthetic, of experiencing life in the moment.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Margot Fonteyn: A Life, by Meredith Daneman

Daneman’s sensibilities, thinking, and writing style are insufficiently sophisticated for the task of making Fonteyn live on paper. I suspect only a poet would be equal to it. Village Voice 12/14/04

THE FRENCH HAVE A SCHOOL FOR IT

Demonstrations of the École de Danse of the Ballet de l’Opéra National de Paris (School of the Paris Opera Ballet) / Opéra National de Paris: Palais Garnier, Paris / December 5, 2004

The Paris Opera Ballet School, founded by Louis XIV in 1713—it’s the world’s oldest academy for producing classical dancers—is now located in a utilitarian complex specifically built for it in Nanterre, on the bleak outskirts of the City of Light. But for more than a century it was located in the bowels of the lavish Palais Garnier, at the hub of urban elegance. It was there—cocooned in that opera house’s imposing Second Empire decorative excesses of varicolored marble offset by gilt and bronze; of statues, bas-reliefs, frescos, and mosaics; of deep red plush and heavy figured and tasseled drapery; of an infinity of mirrors and chandeliers—that I saw the daylong program this extraordinary school, the oldest and arguably the greatest of its kind, modestly calls its “Demonstrations.”

The program, nearly six hours long, with a break midway in which valiant spectators went out to revive themselves with shots of strong black coffee, comprised separate mini-classes for boys and girls from Level 6 (ages 12 to 13) up to Level 1 (18 and under). (You work your way up in this system, those who stay the rigorous course graduating into the parent company or a life in dance elsewhere, at the age of 18, though the precocious may join POB earlier.)

The gracefully and intelligently constructed instruction samples were led by the regular teachers attached to each group, most of whom have been dancers with the parent company. Introductions were performed by Elisabeth Platel, a former POB star, who this year succeeded Claude Bessy, the formidable woman who led the academy to new heights in the course of her three-decade tenure. The grandeur of the Palais Garnier setting provided an elaborate frame that underscored the importance and dignity of the process being revealed on stage—the development, by means of a system begun some 300 years ago, of exquisite dancers. Seeing the succession of children and adolescents methodically attaining professional capability in their esoteric art was like watching one of those films that show a flower unfurling from bud to blossom—always itself, always expanding.

The goal of the youngsters’ scrupulous training, it would seem, is threefold. The most obvious aim is for precision, which permits the uncanny clarity these pupils display at every level of their development. The mark their bodies make in space, while it never relinquishes its sculptural dimension, recalls the fine, incisive lines of an etching.

How is this achieved? Guessing from what I saw, there are several contributing factors, starting with the selection of youngsters physically apt for the work (and the yearly weeding out of those who, for one reason or another, prove unsuitable). Once begun, the training continually emphasizes an independence of the upper body from the lower body, achieved through a fierce command of the mid-section. This allows the young dancer to control what the legs and feet are doing while the torso, arms, and head tell a separate but complementary story. Simultaneously, there’s an intense cultivation of mobility in the hips, knees, ankles, which lends the dancing its all-important fluidity.

A significant aspect of the teaching process, apparently, is the anatomization of steps. At the barre and in the center, steps are minutely taken apart—deconstructed, you might say. Astonishingly, when the discrete elements are reassembled into the complete step, the calculated effort all but disappears, and the step is produced with confidence and ease. For example, the youngest boys perform an exercise for tour en l’air (jump straight up, legs neatly together, turn a full circle without wavering while in the air, and land, still utterly composed, neatly on the take-off spot). As if the sequence were a valuable fragment of choreography, they essay quarter turns, half turns, and three-quarter turns—in both directions, without leaving a clue to the fact that every dancer has a strong and a weak side—and then, triumphantly, the full turn. The feat is produced with such exactitude and with such an air of repose that the audience awards it the kind of fervent response usually reserved for virtuosi at their most spectacular. Boys only a year or two older execute one-and-a-half turns with equal equanimity.

This anatomization, which leads to freedom rather than the constriction you’d predict, is just one aspect of the process the school employs to develop bodies that might well be described as machines for dancing. Yet the POB students are in no way automatons. Equally important in their schooling is an insistence on musicality. As soon as possible, exercises are turned into dancing, where mere accuracy is transformed, animated, made memorable by flow and rhythmic inflection. Shepherding the advanced girls through an intricate exercise in multiple pirouettes—nothing if not a test of sheer technical prowess—the instructor utters only one admonition: “Use this music well.”

Pervading the entire POB academy’s process, it seems to me, is the cultivation of aristocratic virtues, among them elegance, refinement, understatement, the illusion of effortlessness in the most challenging endeavors, and conduct governed by beautifully honed manners. Even the youngest boys on view seem to be descendents of Renaissance cavaliers—gentlemen at once skilled horsemen, lovers, soldiers, diplomats, and poets. The girls who are their counterparts—and foils—possess incomparable delicacy and charm, along with a self-possession suggesting half-hidden capabilities that might enable them to rule the world.

The gaucheness that goes hand in hand with adolescence has been repressed in these aspirants to a remarkable degree. Awkwardness, the weakness that often accompanies growth spurts, the plumpness that goes hand in hand with a newly maturing female body—all these are denied to them. Vulgarity is equally unknown to these young practitioners; apparently, it has been extirpated from their lives. Their dancing is not allowed the slightest degree of gymnastic distortion; their line is utterly pure. The 14-year-old girls of Level 4, a group of long-stemmed lilies, stand in a profiled row at the barre to display their arabesque and, though their extensions are now spectacular, they are kept scrupulously within the boundaries of classical harmony.

Nothing is allowed to appear difficult. POB style insists upon the dancing that is invariably light, gentle, and smooth. Thus, grands battements (ferocious high kicks), even when they’re executed without any support, reveal no visible expenditure of energy. In the same way, multiple pirouettes are spun out as if they were part of the silken filament of a spider web. Huge traveling leaps seem to float—like petals or leaves, released by a breeze from their stalks or branches. (Théophile Gautier, the nineteenth-century French poet of the dance, would have made much of this.) No matter how much virtuosity is required of these youngsters, their audience rarely hears a footfall.

Masters of composure, the students at every level finish each sequence of movements required of them in a perfectly harmonious pose, which they hold, calm and still, turning themselves into living statues. Suffused with dignity, grace, and a self-confidence that’s modestly worn, they offer themselves to be admired.

The senior classes reveal the results of the POB system. The young women, in their pale rose or ivory costumes—the simplest elaboration on practice dress, but ravishingly cut—resemble a cluster of porcelain figurines. At this advanced point in their schooling, every single one of them has been transformed into a creature of the stage. Slowly and almost secretly, they’ve learned to seduce the spectator with their dancing, and, little by little, each of them exudes a unique temperament, like a personal perfume. In partnered adagio, the men concentrate on the intricacies of the support they’re providing, but the women—as with adolescents in real life, more sophisticated than their male peers—seem to harbor a secret excitement vis à vis their partners.

On their own, these 16- to 18-year-old ingénues display sparkling footwork that makes you think of water drops set in play by an exuberant fountain. Their extensions fly high, as do their huge cross-stage leaps, yet everything appears unforced. The beautiful alignment in which they’ve been schooled from the start—and can now maintain even when they’re sweeping through space—has become second nature, and they’ve learned to make the correctness that governs their most complicated and difficult feats look like child’s play.

In the 17- and 18-year-old men, the stripling look of boys just a year or two junior to them has given way to a firm manly build. This year’s group is a vintage crop; in most of them, the quality of dancing seems to predict stardom. They offer a demonstration of double pirouettes from every conceivable position, each ending with the working leg extended high into the air: in attitude, stretched to the side, or reaching arrow-like for the stars. This is followed immediately by cascades of small jumps, fleecy and buoyant, and then by jumps with beats in which the legs work like incisive Solingen scissors. (Most dancers are turners or jumpers; these fellows aspire to be both.) One by one, a half dozen of them execute a manège of tours jetés with the back leg curved, unwavering, in attitude. Then the most courageous of the lot offers a circle of barrel turns in which, at the very top of the arc he outlines in the air, he seems to rest, as if in an inverted hammock. Perfectly poised finishes give the final touch to an accomplishment that is little short of stupefying.

In addition to their graded classes in academic dance (the danse d’école, with partnered adagio as a special department), the students have supplementary lessons in mime, folk dancing, character dancing, modern dance, and some mysterious endeavor called “chorale,” which had the youngest children singing or speaking and moving at the same time in archly playful material. All of these “extra” subjects were represented on the program with an almost reverential acknowledgement of their importance (secondary yet essential) in forming a fully-equipped classical dancer.

The display of mime instruction began with basic exercises for the solid grounding of the body (which contradicts the ballet dancer’s eternal impulse to be airborne) and moved on to matters of weight displacement, the exaggerated isolation of body parts, and the use of the face. With these articulations of stance, gesture, and facial features, the performer learns to convert physical expression into emotional expression and acquires the ability to make the actions of a wordless body tell a detailed story. The style on view was that of the commedia dell’arte, an earthy street theater, and the young pupils entered into it with enthusiasm. Their display culminated with a simultaneous improvisation in which each student acted out his unique version of a madcap narrative—it opened with the preparation of dinner and somehow wound up with a burglary—dictated by the instructor, who cautioned them, as they dealt with dozens of invisible props, “Give every object you touch its proper weight.”

Weight is a primary issue in character and folk dancing, too, along with rhythmic complexity, dynamics, and relating to one’s partner. “On ne danse pas seul, hein?” (You’re not dancing alone, right?), remarked the character dance teacher, as she imitated the 14- and 15-year-olds’ shy indifference to each other when they coupled up for a Polish mazurka. On a second go, some of them managed a little eye contact, even a complicit smile. Next they launched into a series of intricate space-and-timing maneuvers, first executed neutrally, then with a Spanish flavor. “You think too much,” their teacher cried out. “You seem so glum. When you do it that way, it has no interest whatsoever.” Obviously, this indomitable lady takes it as her mission to inject them with spirit: “Quickness of body! Quickness of mind! That’s what you need. Eyes! Eyes! Eyes!”

The more mature teenagers’ character class showed them doing a special barre that evoked, in turn, the national dances of Hungary, Poland, and Spain. The young women were duly outfitted for the occasion in heeled shoes, the young men in red boots. First they worked in an aristocratic mode, with the instructor urging them to be “very grand, very sumptuous.” Then they shifted into the peasant manner, with much clapping of hands, much flexing and stamping of feet. “The face, the face,” their teacher called over the music and the body percussion. “Animate the face. Don’t close the shutters!”

The senior students demonstrated modern dance in the manner of Martha Graham. Everyone was appropriately barefoot, the young men bare-chested as well, the young women in vermilion tops. Like most ballet practitioners confronting Graham’s singular, visceral technique, they operated from the outside in, trying to replicate the look of the material, rather than from an energy source at the core of the body, as the genre requires if it’s to be authentic. And of course it was impossible for these students to shed the habits of their own highly evolved language, in which they’ve been rigorously schooled since childhood. The instructor, who evidently knows full well what she’s up against, remained undaunted, encouraging them to summon up more force and, interestingly, amplitude. In the floor exercises they remained merely decorative. However, at the peak of the traveling work, they suddenly tore through the space, devouring it like panthers, proving that their gift—and it’s a lavish one—is for dancing, not merely ballet.

The achievement of the Paris Opera Ballet’s academy has its human cost. As with any program effectively training children to become topnotch professional dancers, a fierce system of selection and discipline is imposed on minds, bodies, and spirits too immature to give meaningful consent to their fate—and the process has its casualties. Nevertheless, the lure for the children and their parents and guardians remains irresistible. Who does not, at one time or another, aspire to be perfectly beautiful? The difference between the young people who emerge successfully from this extraordinary education and the blessedly ordinary people who constitute most of the world’s population is that Terpsichore’s chosen ones aspire to this transfiguration far more intensely than “normal” types, and more steadily. Observed in the course of their formation, they become, collectively, a work of art in itself, a phenomenon that takes your breath away.

Photo: Photos Icare: Students of the School of the Paris Opera Ballet: (1) Level 5 girls; (2) Senior students in a demonstration of partnered adagio work.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

CHEERING UP

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / November 16-21, 2004

I’m having a lot of trouble with Pina Bausch’s work these days. As just about everyone has noted, the German choreographer whose dark and dirty dance-theater extravaganzas were once hailed as marvelously radical, has, in the last decade, been producing pieces that are gentler, tamer, ostensibly more mellow. In the productions with which she made her name in the States in the 1980s, Bausch took the position of a plaintive, damaged witness to a numbingly reiterative existence in which individuals shuffled between melancholy isolation and hostile matings. Gradually, however, she has turned into a proselyter for the possibility, at least, of pleasure, even romantic love. Bausch Lite, folks are calling the present mode.

I found most of the early work loathsome—hardly dancing, conceptually sophomoric, self-indulgent, and dull—but in retrospect I prefer it to Bausch’s mature-phase tactics. When I think back, the early, tediously unpleasant stuff seems to me at least sincere—Authentic Bausch. In the latest work to hit BAM, the 2002 Für die Kinder von gestern, heute und Morgen (For the Children of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow), some of the old devices—mean and heavily ironic—appear, but mostly as tics, automatic throwbacks to earlier procedures, rather than events that register with the striking vehemence of a mood or idea that goes straight from impulse to metaphor.

An interesting symptom of Bausch’s evolution is the minimizing of the grunge element. In the course of the pieces that made her an art-world celebrity, Bausch could be counted on to produce a filthy, intentionally disgusting stage floor. Dirt, liquids, crazily mistreated food, crushed blossoms—you name it—were routinely smeared, splashed, or strewn on the dancing ground and subsequently massaged into it by treading, flailing, falling bodies. The effect resembled the mess a child makes naturally (or in fits of gleeful misbehavior) with its food or excrement. And of course it referred to the fallout from sex.

Now the housekeeping is immaculate. Even the small puddles of water or the few drifting petals that happen to sully to the pristine white floor in the course of For the Children are neatly picked up or tidily wiped away. Similarly: Bausch’s people originally appeared in garments scavenged from thrift shops—ill-fitting and evocatively downscale castoffs, just right for the savaging they’d get as the action progressed. Now the performers have a costumer, Marion Cito, and the women’s gowns are ravishing. (Each lady sports several changes.) In the Bad Old Days, makeup was largely Hallowe’en Garish and often put to lethal purpose (a guy, say, using lipstick to paint graffiti on the naked back of his female victim). Today, the women are as cosmetically beautified as mannequins readied for a Vogue shoot. Female armpits and legs that went defiantly unshaven are now smooth, and their owners have gone to the trouble, it looks like, to extend their foundation from face and neck to arms and upper torso like a pack of conscientious ballerinas suiting up to play Odette, Queen of the Swans.

Like all of Bausch’s pieces, For the Children proceeds by increments—over nearly three hours. Vignette follows vignette; structure is loose; meaning—even message–remain vague. Some segments, most of them sappy—the full cast pretending to be butterflies or building sand castles—may refer to the dance’s cryptic title, which, I assume with regret, refers to adults’ contacting their Inner Child. Several disjunctive solos depicting a kind of psychic falling apart provide the show’s most eloquent moments. The most bizarre passages include a group of drop-dead glamorous women in black raking parts into their hair with their stiletto-heeled pumps; nasty uses of fire to mutilate clothing, flesh, and, pointedly, a book; plus the customary Bauschian variations on the theme of humiliating courtships and bad sex.

A good part of the show’s second half is devoted to free-for-all dancing—high-octane displays of physical bravado that owe much to break dancing, skate boarding, and the wild improvisatory action that occurs in clubs where the refreshments are mind-bending. The idea seems to be that physical ecstasy equates with psychic triumph or release. Twyla Tharp used this ploy in the “Golden Section” of The Catherine Wheel; the finale of Harald Lander’s Études can be thought of as an early prototype. Bausch’s grand slam finale doesn’t earn what it’s aiming for, though. In no way is it the logical outcome of the events preceding it; it appears to be tacked on, in desperation. Neither can it lay claim to any intrinsic choreographic merit. It looks like raw improvisation, edited only to avoid collisions.

Despite the shift in emphasis in Bausch’s work from acting to dancing, most of the fifteen technically accomplished members of the cast register as distinct personalities. Ditta Miranda Jasjfi, childlike in appearance, is remarkable in her pathos and stubborn resilience, while two veterans—Nazareth Panadero and Dominique Mercy—recall the peculiar, unique force of the old-school Bausch performers. Panadero, with her gravelly voice, her blithe, firm stride, and her vivid self-projection, is primarily neither dancer nor actor but sheer personality. Though she skirts the edge of self-parody, audiences still adore her appetite for life, her nerve, her way with a blood-red lipstick. Mercy is her opposite—mild-mannered and physically unassuming. He makes the most of that recessive quality, operating like an anonymous man in the street, wrapped in a thoughtful, slightly troubled, inner-directed air. Invariably, he’s cast as a person to whom things happen, not one who initiates events. His secret ace? His tremendous dignity; it pervades everything he does. Mercy’s best moment in For the Children—more telling even than his pair of quietly riveting man-at-the-end-of-his-rope solos—finds him clad in nothing but a supersized tutu; instead of a fig leaf, there’s this huge cloud of chiffon fluff. He crosses the stage in this absurd outfit, his manner entirely uninflected, wielding one of those French galvanized-tin watering cans, as if to sprinkle the dance floor, as the youngest “rat” of the Paris Opera did, to prevent skidding accidents, in a time immortalized by Degas. Not an iota of Trockadero-style comedy intrudes into this strange small escapade; Mercy makes it all grave beauty.

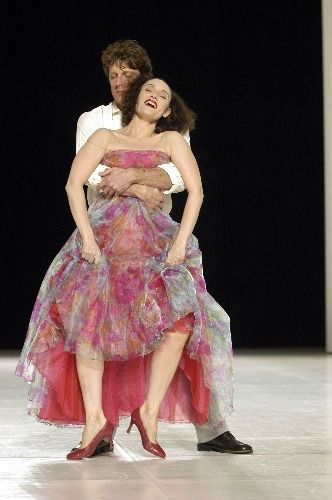

Photo: Stephanie Berger: Nazareth Panadero with Pascal Merighi in Pina Bausch’s Für die Kinder von gestern, heute und Morgen

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

IB ANDERSEN & BALLET ARIZONA AT THE GUGGENHEIM

Works & Process at the Guggenheim: Balanchine Continued . . . at Ballet Arizona / Guggenheim Museum, NYC / November 14 and 15, 2004

The first program in a series of four exploring the ongoing life of George Balanchine’s legacy showcased Ib Andersen, one of the most glorious of the Danish male dancers who “defected” to the New York City Ballet to be part of that incomparable choreographer’s world, and nine dancers of Ballet Arizona, where he is now artistic director.

With the company’s permission, I watched early afternoon class the day of the first performance. On a chilly stage, on a floor that was sticky in some places, slippery in others (these flaws would be corrected by curtain time), without musical accompaniment, Andersen put his dancers through their paces. Despite these less than favorable circumstances, it was evident that he has been managing, very effectively, to transmit key principles of the Balanchine style. The dancers’ work was brisk and clean; its goal seemed to be execution that is eloquent in its very stripped-down efficiency. Refusing the decoration or sentimentality that can prettify the classical vocabulary but inevitably smudges it, this way of working lets the step speak for itself.

Once the dancers moved from the barre to the center of the space, they revealed, in addition to swiftness and clarity, a sculptural dimension as well as a welcome individuality of physical type and temperament. This last made me recall the New York City Ballet of the fifties, when the company, of necessity, harbored a more variegated range of dancers than it does today, with a limitless talent pool available to it.

Like Balanchine before him, Andersen is a man of few words in class. He doesn’t explicate and he doesn’t exhort. He sets the steps—in canny, challenging combinations—watches keen-eyed, and corrects sparingly, matter-of-factly, and unerringly. Under his aegis, I imagine, one could learn quite a lot.

Andersen’s own choreography, seen in the evening’s performance, is another matter. On a single viewing, I found it baffling. He presented solos and duets drawn from a lengthy work, Mosaik, each excerpt to music from a different composer, and segments of Elevations, to Handel. With few exceptions, this choreography is simply not dancey. For whatever reason, Andersen chooses not to do what the music is saying, even dictating. Despite the allurements of the score, his choreography remains aloof, disengaged. It has other agendas, it would seem, but at first glance they’re unfathomable.

Much of the choreography is adamantly spare, and its steps or small clusters of steps refuse to connect. One thing is done, then another. Then another. To what purpose? one keeps wondering. And why the pauses in the action that are like pockets of dead air? A few of the dances seem to be very brainy, comments on the music rather than an emanation from it, or reflections on a “concept.” The Mosaik solo to some upbeat Rossini, for instance, charmingly danced by Astrit Zejnati, might be a deconstruction of bravura work. Another solo from the same piece, to which Joseph Cavanaugh brought admirable gravity and weight, suggested the half-life of a god sculpted in stone. But ideas don’t dance with much alacrity; indeed, they’re inclined to stasis.

When it comes to theme, Andersen seems to be preoccupied with isolation, alienation, estrangement—that is, with people remaining distanced even when they are coupled, with action that thwarts the body’s natural impulse toward coordination and flow. The results include perverse lifts and entanglements and an atmosphere dismayingly devoid of vitality.

All of this seems to contradict the dancer he once was: musical; lyric; a quicksilver athlete; a creature of the air, buoyed, it always appeared, by an ecstatic vision; a performer who had located his rightful artistic home.

The program offered two Balanchine items: the sublime adagio from Divertimento No. 15, which is danced by five couples who appear in sequence, like poignant but fugitive images amplifying the transcendent beauty of Mozart’s music, and the duet from Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.

The Mozart ballet was beautifully done, the dancing profoundly musical and filled with delight. The women, in particular, aimed for the kind amplitude that once—but, alas, no longer—made NYCB audiences weep in response to the sight and sound, perfectly combined, of ineffable beauty. Their cavaliers provided careful, sympathetic support. Everyone, despite individual limitations of anatomy and talent (blessings so cruelly rationed by the gods), rose to the occasion with an elegance of bearing that spoke of classical dancing’s aristocratic roots and a purity of intent that has become all too rare. This is the sort of mass transformation that only excellent artistic direction—based on taste, vision, and endless labor in good faith—can bring into being. The dancers were Lisbet Companioni, Michael Cook, Nancy Crowley, Paola Hartley, Natalia Magnicaballi, Kendra Mitchell, Elye Olson, and Zejnati.

The rendering of the Slaughter duet was, to my mind, diminished by a dimension lacking in its dancers. Magnicaballi and Cook, both fine as far as they went, didn’t go far enough into the realm of raw—adult—sensuality. They seemed to be a pair of teenagers astonished to find they’ve fallen crazily in love, like the appealing adolescents in a Robbins ballet. This lightweight reading is not what Suzanne Farrell (in whose company Magnicaballi dances) used to give us.

In between the segments of dancing, Andersen was interviewed by Lourdes Lopez, a former principal dancer at the New York City Ballet who is now executive director of the Balanchine Foundation. She is a perfect ambassador for dance, combining a keen intelligence with a gracious manner. She elicited from Andersen, who used to be shuttered in interviews, thoughtful comments on his handling of the Balanchine legacy and a vivid picture—frank, warm, and tinged with Danish irony—of his position as artistic director of a small company operating far from the hubs of classical dancing.

Here are a few fragments of their conversation—as accurately as I could record them on the fly:

IA, commenting on an amateur film Lopez screened that showed him at his fleetest, rehearsing one of the Mozartiana variations choreographed for him, with Balanchine applauding him at the finish: He used what I could do then.

IA, on Balanchine: Dancing his ballets was an education of how to be in life.

IA, on staging Balanchine’s ballets: I teach the steps and I teach what I think his intent was. It’s what I think he intended, which is of course not [necessarily] what he intended. And, like everyone else who stages Balanchine’s ballets, I put something of myself into it—because what else can you do?

LL: What do you think Balanchine wanted to see [in dancing]?

IA: Expressive bodies.

IA, on his position with Ballet Arizona: Arizona is pioneering country. A lot of people there don’t know much about dancing. Some do, but a lot don’t. You give that audience what it wants, and then you give them something that challenges them. I’m lucky enough to have shaped my own environment there. (Half joking) I tell the board of directors what they should think.

LL: (Laughing) That’s the Balanchine legacy in a nutshell.

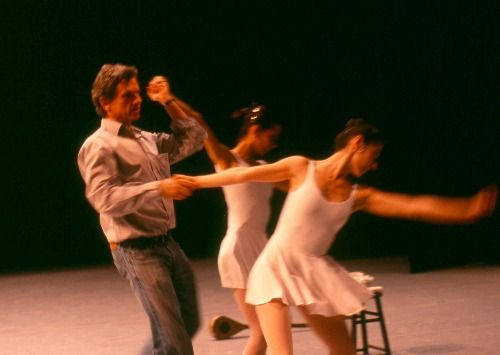

Photo: Harrison Hurwitz: Ib Andersen in rehearsal at Ballet Arizona

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Monica Bill Barnes

At each of their recurrent impasses, unable to establish a mode of togetherness that will last, yet determined not to part, they face each other as if to ask, “Where do we go from here?” Village Voice 11/15/04

RUNNING IN PLACE

Mandance Project / Joyce Theater, NYC / October 21 – November 7, 2004

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, as the French say. The more things change, the more they remain the same. The proverb might have been generated to describe Eliot’s Feld’s choreographic career. Feld’s latest company, Mandance Project—consisting of five men and a lone woman—recently made its debut in New York with a repertory of 11 dances, all but one of them brand new. Astonishingly, the work looks like much that Feld, a huge but inexplicably stymied talent, has been doing for the last quarter-century. The pieces—six of them on the program I saw—are typically astutely crafted but rigid, confined, and obsessively repetitive. The very antithesis of early Feld works like Intermezzo and At Midnight, they say no to organic flow and depth of feeling, substituting aren’t-I-clever? gimmicks for the qualities that lie at the heart of expressive dancing.

In Backchat, a trio of ballet boyz climbs up, down, and over a free-standing made-to-look-like-brick wall over and over again, performing the athletic feats of neighborhood thugs in picturesque formations. The wall is only  some 10 feet wide and stands in a vast field of empty stage space, but the three guys remain attached to their prop as if they were shackled to it. It’s not long before the viewer feels shackled too. Granted, Feld wants his audience to feel for these tough yet vulnerable guys; after all, he made his Broadway debut as a teenager in West Side Story. So he allots them a “dream” sequence in which they buddy up in slow motion (“Somewhere there’s a place for us”) and finishes by having them hang upside down from the top of their wall like victims of an atrocious crucifixion. Why, then, does he devote the bulk of his effort to making them look like a video commercial for athletic shoes?

some 10 feet wide and stands in a vast field of empty stage space, but the three guys remain attached to their prop as if they were shackled to it. It’s not long before the viewer feels shackled too. Granted, Feld wants his audience to feel for these tough yet vulnerable guys; after all, he made his Broadway debut as a teenager in West Side Story. So he allots them a “dream” sequence in which they buddy up in slow motion (“Somewhere there’s a place for us”) and finishes by having them hang upside down from the top of their wall like victims of an atrocious crucifixion. Why, then, does he devote the bulk of his effort to making them look like a video commercial for athletic shoes?

In Proverb, the young, sensuous, intensely concentrated Sean Suozzi is stripped to his flesh-tinted jock strap, a pair of Prodigal Son sandals, and lights that he cradles in his palms. These provide what seems to be the only illumination on the stage. At one point, he seems to hold the world’s last spark of fire in his hand; elsewhere the gigantic, blurry shadows he casts on the backdrop threaten to engulf him. Much like similar Feld undertakings, this hackneyed business goes on far too long after it has made whatever point it’s going to make.

Rumors has three men and a woman in s&m black webbing hanging from metal hooks upstage, like meat in a butcher shop window. We peer at them through a downstage row of gleaming jointed metal rods that seem to have some industrial—possibly lethal—purpose. When finally (and not a moment too soon), the figures free themselves and enter the clear available space centerstage, they thrash and droop like a quartet of tortured Petrouchkas, each rooted to his or her individual spot. The finale allows them a measure of locomotion—which they employ to crash noisily through the curtain of rods—but then re-condemns them to their hooks. The suggestion of human atrocities sits ill with the chic look of the dance. Admittedly, this incompatibility has been popular for some time. Did it come to the dance stage via fashion photography or is it merely a sign of these dismal times? Rumors gives you all the time in the world to ponder this question.

A Stair Dance, a tribute to Gregory Hines (and, surely, a couple of older legendary tappers), sets five dancers on five abutting five-step staircases and—guess what?—sends them up and down. Also, in the belated fullness of time, around. Jiving on the steps, the dancers might be notes on a musical staff. The accompanying music is by Steve Reich, a composer to whom Feld frequently turns, almost as if he were using Reich’s repetition, which usually results in a freeing ecstasy, as an excuse for his own iterative compulsions. These, however, are more likely to make viewers feel as if they’ve been sentenced to an indefinite term in a box that keeps (very, very slowly, mind you) getting smaller and more devoid of oxygen.

Yazoo, originally created for Mikhail Baryshnikov, is an endless series of shenanigans with a Western twang, beautifully performed by Wu-Kang Chen. Jawbone, beautifully performed by Damien Woetzel, is yet another one of those Feld experiments in how long you can keep a dancer interesting onstage without material that has any intrinsic interest. Feld, with his exaggerated estimate of that length, has, over the years, reduced far too many superb performing artists to choreography that’s the equivalent of reading aloud from the phone book.

The dancers chosen for the Mandance Project (note the company name’s reference to Baryshnikov’s White Oak Project, with its implication of impermanence) deserve richer material. Nickemil Concepcion, Jason Jordan, and the alluring Patricia Tuthill were the standouts of Feld’s now disbanded Ballet Tech (and trained from the start in its innovative school). They, along with the equally outstanding Chen, hold their own with Woetzel, a veteran New York City Ballet principal, and Suozzi, who has been with NYCB for four years without that company’s yet recognizing his true worth. Mandance makes them look like six dancers in search of a choreographer.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

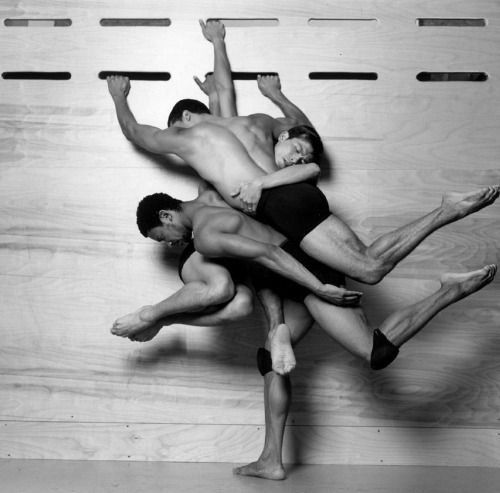

Photo © Bruce Weber 2004: Studio photograph, uncostumed, of Jason Jordan, Nickemil Concepcion, and Wu-Kang Chen in Eliot Feld’s

Backchat.Henning Rubsam / Sensedance

The radiance the program possessed was due largely to the presence of performers borrowed from the beleaguered Dance Theatre of Harlem, who seem to operate from sources deep inside them. Village Voice 11/08/04