First Sight: The Performance

An extraordinary dancer doesn’t need to be discovered. He’s apparent. I had my first, startling, sight of Danny Tidwell last spring in one of the Guggenheim Museum’s show-and-tell Works & Process programs. The subject of the evening was ballet competitions. American Ballet Theatre, which harbors many a medalist, sent a bunch of them out to perform their winning numbers and then, without pause for breath, to chat about the competition phenomenon with John Meehan. Meehan heads the ABT Studio Company—a dozen hand-picked young hopefuls serving a critical apprenticeship. Tidwell, one of these aspirants, opened the show in the Corsaire pas de deux, offering a thrilling glimpse of nascent stardom.

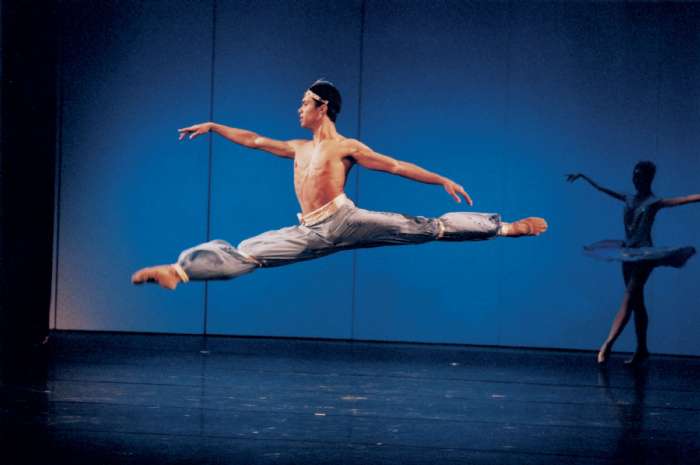

His performance was ardent. Passion for the sheer physical experience of the bravura choreography was fused with a vivid—indeed, blazing—idea of character and situation. It was evident immediately that this guy is a creature of the stage. His energy is extravagant. His technical ability in the big moves—-the huge, powerful leaps, the multiple turns coupling speed with control—is formidable. He grabs space the way a street gang carves out its territory, but he’s never strained or sloppy about it. Launched into the air, his body remains perfectly composed, as if suspended in time as well as place, creating an indelible image. He retains the rawness and wildness of a kid left to grow up on his own. This is balanced, somewhat eerily, with mature self-possession and authority. You look at him and think: This is why I watch dancing. This is the real thing.

His performance was ardent. Passion for the sheer physical experience of the bravura choreography was fused with a vivid—indeed, blazing—idea of character and situation. It was evident immediately that this guy is a creature of the stage. His energy is extravagant. His technical ability in the big moves—-the huge, powerful leaps, the multiple turns coupling speed with control—is formidable. He grabs space the way a street gang carves out its territory, but he’s never strained or sloppy about it. Launched into the air, his body remains perfectly composed, as if suspended in time as well as place, creating an indelible image. He retains the rawness and wildness of a kid left to grow up on his own. This is balanced, somewhat eerily, with mature self-possession and authority. You look at him and think: This is why I watch dancing. This is the real thing.

Second Sight: In Class

Intrigued, I ask to see him in class. Here’s what I notice, besides what I’d already noticed:

He’s got a lush plié, which gives him his extraordinary ballon. Not even the Danes in their heyday could produce a pas de chat as springy on ascent, as cushioned on its fall.

Turning: It’s not the number of pirouettes from fourth position (six, actually) that’s so remarkable. Everybody’s on ball bearings these days. It’s the ease with which he spools them out. It’s the illusion of the body’s rising vertically as it spins. It’s the controlled finish, which is velvety—and confident to the point of appearing almost casual.

Self-possession: He has beautiful line, along with an ability to hold extended positions while exuding calm mastery. He has none of the late-adolescent gawkiness and uncertainty that cling to most of the other young men in the class. While the other fellows are still moving in awkwardly joined pieces, he uses his body harmoniously. He seems more grown-up, more self-contained, more whole than his peers—utterly at ease in his own skin.

Anatomy: Dancing can’t help being about bodies, though the flaws legendary dancers have “overcome” are edifying legends in themselves. This dancer’s feet are somewhat stiff, which is worrisome; he’s unlikely to shine in petit allegro. His thighs are bulky—worrisome, perhaps, in one still so young, but remediable. He’s not tall enough to partner the new breed of Amazon-scaled ballerinas; still, he’s two inches taller than Baryshnikov and the more diminutive ballerina hasn’t gone out of style. As for those muscular thighs, they simply weren’t noticeable in performance. (It’s imperative to remember when scrutinizing dancers in class that, in the end, performance is the only thing that counts.) He has a beautifully shaped head poised on a long, strong neck, and his hands are infallibly elegant. (Always notice a dancer’s hands; they’re as much a key to character as the face.) He’s got a killer smile, which he bestows only, it seems, on people and occasions that have earned it.

Personality: There’s something of the sulky antihero about him. At the barre, he doesn’t exert himself unduly. You wouldn’t single him out from his peers on the evidence of these bread-and-butter exercises—except, perhaps, for his instinctive musical phrasing of them. Later, when the instructor sets a traveling combination so thorny he apologizes for it in advance, Tidwell adds a gratuitous spate of pirouettes and a leg-switching split jeté—with a slightly disengaged-from-it-all air. What’s this about? Boredom? Veiled defiance? His attitude is just the opposite in performance, where he’s all eagerness. Apart from the intermittent displays of disaffection, his manner has an old-fashioned grace. A stage persona is already emerging: macho and at the same time very tender. In this he might be a cousin of ABT’s Jose Manuel Carreño. Above all, he’s noble. A danseur noble in the making.

Insight: The Interview Here’s where you find out, perhaps, more than you want to know, more than you should know. Usually the best thing about an artist is his art. Yet we can’t help being curious. Shortly after the Guggenheim sighting, I get to see Danny Tidwell close to, ask some generic questions, get some surprising answers.

Here’s where you find out, perhaps, more than you want to know, more than you should know. Usually the best thing about an artist is his art. Yet we can’t help being curious. Shortly after the Guggenheim sighting, I get to see Danny Tidwell close to, ask some generic questions, get some surprising answers.

He is eighteen years old. He grew up in a Virginia beach town. “I lived with my original family, my mom and two sisters, until I was about ten. My home life was not, let’s say, an ideal situation.” I’m as reluctant to ask for details about his precarious childhood as he is to offer them. “My dance teacher let me move in with her. I was always at her studio anyway, taking classes: jazz, tap, ballet. Denise Wall’s Dance Energy. I call her my mom.”

Competition and competitions were the spur. “I got outside my own little town and saw so many other kids from all over who were so good—a hundred times better than me—and so excited about what they were doing. That’s where I saw what was happening and what was possible.” He noticed that several of the most adept kids were pupils of the Kirov Academy in Washington, D.C. He decided that’s where he needed to be. Doors open to evident talent; the Kirov Academy gave him a scholarship.

What brought about his conversion from jazz to ballet? “Jazz is raw, edgy, and real. It’s a release. And when you get onstage and the audience receives what you’re doing, it’s so fantastic. Ballet is the opposite; everything you do is about rules. It’s harder to get this dance form across to an audience, and there’s always something you could do so much better. Those challenges keep me interested. Ballet is very idealized and very glamorous to me. You get onstage and you can just stand and move your arms and everyone knows how you want to be. I love the music. I love the movements. I love doing tricks. I love partnering with a girl—the feeling that you’re together with another human being. I love connecting with the audience. I love it all, every part of it.”

“I was at the Kirov Academy for two years. It was the best and the worst experience of my whole life.” The unremitting rigor of the Russian training system, as he describes it, makes the place sound like a cross between boot camp and a monastery. The social isolation only intensified the pressure. The academy is a boarding school for an international crop of gifted students who have nothing in common but dancing and, it would seem, no space in which to do anything else. “I was totally shocked and totally stressed out. It worked for me, developing me as a dancer, but I saw it not working for others.” After a summer of intensive preparation for the Shanghai International Ballet Competition, where he took the silver medal (no gold was awarded), he quit the Kirov program. “I couldn’t live without my freedom.”

“I went home, took a year off and did a lot of finding myself, went to New York and did jobs here and there—you know, Debbie Allen’s shows, stuff like that. Then I got a scholarship to SAB [the School of American Ballet], which I hated even worse than I hated the Kirov Academy, the kids were so unaccepting, the teachers so unmovtivating. I needed to be pushed, I needed to know that ballet was more than just taking class, I needed for someone to care about me. I lasted there about two months.”

The lure of competing saved a career that might have been over before it had even began. Tidwell decided to whip himself into shape “for Jackson” [the USA International Ballet Competition in Jackson, Mississippi—these things have fancy names] and copped the silver. Kevin McKenzie, ABT’s artistic director, saw a video of his prize-winning performance and suggested to John Meehan that he offer Tidwell a place in the Studio Company. No audition was required.

Now, toward the end of a year with this springboard group, Tidwell is sure he has found his place. His immediate goal is a slot in the parent company, though he still keeps up his jazz and acting lessons “so that Broadway will be an option if ballet doesn’t pan out.” Joining the ABT corps, it turns out, is only the first in a series of escalating aims. Call them dreams, if you prefer, but, while Tidwell’s manner is disarmingly modest in talking about them, his focus is precise. When it comes to roles, he hankers after the hero parts, which obviously means attaining high rank on the roster. “I want to do my Swan Lake, my Giselle, my Don Q, my Bayadère. I want to conquer those roles. I’d also like to do Romeo and Juliet. Of course I’d like to learn how to dance Balanchine the right way, but my training has been for those ‘big’ parts. I also love contemporary stuff. I feel sometimes that I’m better at it than I am at ballet,” he adds wistfully.

Stalwartly, he continues, as if, once having confessed to ambition, he can reveal the full extent of his hopes. “I want to choreograph, too. I’ve made some dances already. Naturally I want to be a principal dancer. Then, when I’m finished dancing”—deep breath before he dares to bring it out—”I’d like to be the artistic director of ABT.” He has the grace to pause after this, note my astonished silence, and add, “Well, if not here, then maybe somewhere else.”

Meanwhile, he’s still young enough in his career to be looking for role models. His choices, keen-eyed and intuitive, suit the kind of dancer he promises to become. “First, Jose Manuel Carreño. He’s beautiful. It’s the way his muscles work and the way he makes everything look effortless. His dancing is so clean and clear, and yet it’s not finished, ever. When he’s offstage, you want him to come back, because you don’t want him to finish. And he never does; he never stops. When he performs, he’s not showing off his talent; no, it’s a conversation with the audience. He seems to be saying, ‘I’m dancing for you.’ This is so comforting and inspiring.

“Then Carlos Acosta. He’s a freak of nature. He’s so tall and his movement is so huge. He’s such a story. When he runs—well, he’s just this big, massive man just running and turning and jumping. He defies gravity and he turns more than you’d ever think possible—and he still holds his fifth position perfect. Amazing.

“And Desmond Richardson, especially in his contemporary dancing, which is absolutely brilliant. You should see him in hip-hop class—moving and isolating and just living.”

“But the one is Jose Manuel.”

Fast Forward

Shortly after our interview last spring, Tidwell’s career took off. The Studio Company toured to Belfast and London, where, according to eyewitness reports and newspaper reviews, the young dancer was a sensation. Back in New York, following performances at the Kaye Playhouse, he was summoned by the parent company to join its ranks, without having to do the customary apprentice stint. Like every newcomer, he learned a slew of corps de ballet roles and, with just a single rehearsal, carried out a soloist assignment—the bravura Neapolitan Dance in Kevin McKenzie’s Swan Lake. “He did tremendously well,” John Meehan reports, adding dryly, “He has not gone unnoticed by the powers that be.” At the same time, Meehan counsels patience. “In a large classical ballet company, you have to learn to wait.” And Tidwell himself has grown more temperate—cautious, perhaps—in expressing his hopes for the future. He’s still going for the gold but reports, “This is my year for observing.” Meanwhile, New York balletomanes will be observing him, in the course of ABT’s upcoming engagement at the City Center, October 22-November 9, which will feature two of his role models, Acosta and Carreño. Every move these heroes make will serve the young dancer as a lesson.

Coda

Will Danny Tidwell be “the one” of his generation? There’s no telling, really. To become and remain a memorable dancer takes staying power, the kind of talent that continues to expand as it rises to ever-increasing challenge, an imagination that refuses to be extinguished by the relentless pressure of the banal—and lavish good luck. Whoever the great ones in the rising generation turn out to be, though, right now they probably look a lot like Danny Tidwell.

Photo credits:

1. Rosalie O’Connor: Danny Tidwell in Le Corsaire

2. Marty Sohl: Portrait of Danny Tidwell

© 2003 Tobi Tobias