Royal Danish Ballet / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / September 20 & 21, 2003

Copenhagen

Nearly two centuries after August Bournonville’s birth, the ballets of this peerless Romantic-era choreographer and the unique style in which they are danced still define the profile of the Royal Danish Ballet. The Bournonville heritage calls for dancing that is both fleet and buoyant, delivered with an effortless air. Simultaneously, it demands acting that tells a story clearly, animated by emotions that are deeply and truly felt. Danish dancers’ loyalty to this tradition has had its ups and downs because of the perennial yen to be up to date, but at heart the Danes know that Bournonville is the key not just to their past, but to their future as well. The 1836 La Sylphide, Bournonville’s first big hit, is produced all over the world today, yet the RDB rendition remains the definitive one.

While I was in Copenhagen, the company unveiled its new staging of La Sylphide at the Royal Theatre, a late nineteenth-century jewel box, in the presence of the Danish queen, Margrethe II, herself a balletomane. The production was entrusted to Nikolaj Hübbe—a senior principal with the New York City Ballet who is Danish-born, trained from childhood in the venerable school of the RDB, and one of several superb Danish male dancers who left home for the States early in their careers, lured by the siren song of Balanchine. Hübbe’s assignment seems to be part of a move by the RDB’s present artistic director, Frank Andersen, to hand over to a new generation the responsibility for keeping the Bournonville repertory faithful to its roots yet alive in the present moment.

While I was in Copenhagen, the company unveiled its new staging of La Sylphide at the Royal Theatre, a late nineteenth-century jewel box, in the presence of the Danish queen, Margrethe II, herself a balletomane. The production was entrusted to Nikolaj Hübbe—a senior principal with the New York City Ballet who is Danish-born, trained from childhood in the venerable school of the RDB, and one of several superb Danish male dancers who left home for the States early in their careers, lured by the siren song of Balanchine. Hübbe’s assignment seems to be part of a move by the RDB’s present artistic director, Frank Andersen, to hand over to a new generation the responsibility for keeping the Bournonville repertory faithful to its roots yet alive in the present moment.

To his great credit, Hübbe has not meddled with La Sylphide in the sense of marring it with latter-day “concepts” and gimmicks, as contemporary directors are fatally tempted to do. He has also refrained from imposing a specific meaning on the ballet, which is rich in metaphoric possibility. It tells the tale of a young man (James) who forsakes his fiancée (Effy) and the down-to-earth Scottish farming community she represents to pursue a dangerous dream of ecstasy, following the Sylphide, a creature as poetic and ephemeral as a drifting cloud, out into the wilds. Hübbe’s reticence in dictating a point of view—though cynics may take it as evidence that he doesn’t have one—is probably all to the good. It leaves the production room to develop one slowly and organically, through successive performances. This process is, fortunately, a Danish specialty.

Hübbe has retained the basic choreographic text established for the ballet in the middle of the last century, just clearing the air a little here and there where he sensed fustiness had accumulated and obscured the view. For the most part, he respected the “old-fashioned” qualities of the ballet, his one significant alteration being to accelerate the tempo. This, I think, was a mistake, as it robs both the dancing and the mime of the weight and calm both need in order to register. I can’t say to what degree he coached the leading dancers in their roles or to what degree he left these resourceful artists to their own devices, but the resulting performances—in the leading roles and the all-important secondary ones as well—were astonishing.

Thomas Lund, an exemplar of the Bournonville style, played James. At the peak of his performing career, Lund offers his technical prowess as a given. His space-seizing leaps, shaped with infallible grace, float in the air; their landings are confident and lushly cushioned. Swift and rhythmically precise, the multiple beats that adorn his jumps bring to mind the heartbeat of a bird. Timing is everything in Bournonville, and Lund gives the choreography, in danced and mimed sequences alike, the musical phrasing essential to it. In this new production, though, Lund has come alive as an actor for the first time. Perhaps modeling his approach on Hübbe’s own dramatically fervent James, Lund creates a powerful and original temperament. In his James, the appearance of the Sylphide suddenly awakens an overwhelming unconscious desire to escape the world he knows. This James is utterly disconcerted—even to the brink of madness—by the prospect of abandoning the familiar for the fatal attraction of the unknown and irrevocably doomed to do so. Lund takes the risk of working at the outer margin of control and it makes for the kind of theater in which the performer himself, caught, all senses aflame, in the middle of the story being told, doesn’t appear to know how it will end.

Gudrun Bojesen, making a remarkable home-base debut as the Sylphide, is the prototype of the Danish ballerina, operating in a golden glow, all tenderness and radiance. The ideal relates to the beauty embodied in Danish Golden Age painting, contemporary with the first half of Bournonville’s life—a loveliness that needn’t proclaim itself but can serenely wait to be discovered. Bojesen is the most adept female Bournonville technician of her generation, and her scudding-cloud lightness and instinctive musicality serve her particularly well in this role. Fresh, natural, and spontaneous, by turns dulcet and capricious, her Sylphide is an innocent, as unaware as sun and rain of the consequences her behavior effects. Though she has only just gotten started on the role—her death scene will no doubt acquire more texture—she is the most wonderful Sylphide I’ve seen.

It’s early days, too, for the interplay between Bojesen’s Sylphide and Lund’s James, but the pair have made a sensitive start on the partnership and a few moments are already perfect. When the Sylphide appears at James’s window, lighting up the dark room in which he dwells, Bojesen and Lund remain utterly still, gazing at each other as they recognize their mutual desire: You—nothing and no one else—are what I want. Then they let their open arms fall, slowly and simultaneously, as they stand in awe of their happiness, alas a tragically fleeting one. The moment goes beyond La Sylphide to the very purpose of art, which is to convey to us what it means to be human.

The performances of the second-cast Sylphide and James were fine enough, but something of a letdown when seen in the shadow of the first cast. The veteran principal dancer Rose Gad, who looks like a Dresden china shepherdess, delivered her familiar exquisitely studied rendition, but her heart no longer seems to be in it, and its filigree quality has begun to blur. As James, Mads Blangstrup aims, rightly, at hectic passion, which now just requires a clearer focus. His technique isn’t as solid or confident as Lund’s, though, and his dancing is nowhere nearly as well phrased. Gad and Blangstrup were at their best in the final scene, where James destroys the Sylphide who has simultaneously tempted and eluded him by finally possessing her. Blangstrup’s James becomes the picture of uncontrollable desire succeeded by anguish, while Gad’s Sylphide dies a picturesque and quite moving death.

The role of the witch, Madge—as pivotal a character in La Sylphide as the Sylph and James, being the catalyst for the plot’s calamities—is haunted by the searing interpretations Sorella Englund has given it over the last two decades. Jette Buchwald, making her debut in the part in this production, is promising. She needs more time, though, to clarify and deepen her interpretation, as well as the courage to trust more to visceral emotion and depend less on the careful thinking that invariably characterizes her work. Lis Jeppesen, in her ballerina days an irresistible soubrette with a streak of dramatic passion, has so far been a disappointment in the mime roles Bournonville’s ballets offer dancers in mid- to late-career. Her Madge, unfortunately, is no exception. Jeppesen hasn’t yet been able to shed the ballerina’s poised-for-flight stance for the rooted, gnarled moves that are a mime’s province. (The transition can take years to accomplish.) She also needs to curb her instinct for self-mockery, a defensive mechanism that keeps her mime portrayals shallow.

The secondary roles of Effy and Gurn (the stolid suitor she accepts on the rebound) were imaginatively cast and sincerely played. I wonder, though, if Hübbe hasn’t encouraged his Effys to be somewhat too tragic when James jilts them to pursue the Sylphide. I suspect that, for all Effy offers of a warm, settled life, what she lacks as a prospective mate for James is the capacity for tragedy that goes hand in hand with the ability to experience the utmost reaches of joy. Isn’t it this very limitation—the stultifying this-far-and-no-further code of bourgeois life—that makes James forsake hearth and home to follow the Sylph?

In the cameo role of Anna—the nurturing mother figure who tries to keep her little close-knit society on an even keel, shielding it from the disaster inevitable when wild dreams are allowed free rein—Kirsten Simone embodied Danish ballet tradition. A former Sylphide and a former Madge, Simone played the small part now assigned to her with inexhaustible attention to detail, reacting fully and truly to everything happening around her and to her fellow creatures in the action. But she managed all this with a carefully modulated intensity, never threatening to steal the spotlight from the ballet’s chief figures and their fate.

The ballet’s new décor and costumes, by Mikael Melbye, are neither highly original nor particularly enhancing. (I had hoped for much more after seeing Melbye’s designs for the Royal Danish Opera’s production of The Magic Flute, which respond to the fantasy of Mozart’s theme and music by devising a world a child might imagine if he’d been nurtured on myths and picture books.)

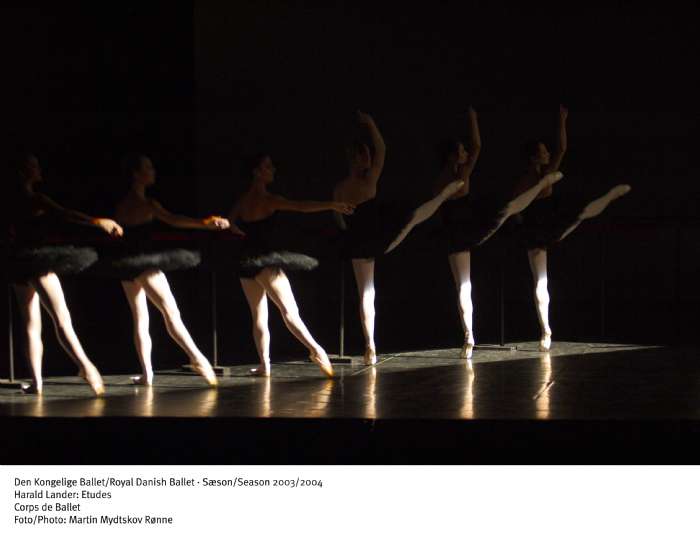

In a program aiming for high contrast, La Sylphide was followed by another Danish staple, Harald Lander’s Etudes, created in 1948 on the RDB, then revised for the Paris Opera Ballet, when Lander left Denmark for France. Artistic director of the Danish company from 1932 to 1951, Lander played the key role in its transition from a history-laden institution creating wonders at home, isolated from the view and the influence of the wider world, to a significant position in the international dance community. He was also a prolific choreographer, but hardly a top-notch one.

In a program aiming for high contrast, La Sylphide was followed by another Danish staple, Harald Lander’s Etudes, created in 1948 on the RDB, then revised for the Paris Opera Ballet, when Lander left Denmark for France. Artistic director of the Danish company from 1932 to 1951, Lander played the key role in its transition from a history-laden institution creating wonders at home, isolated from the view and the influence of the wider world, to a significant position in the international dance community. He was also a prolific choreographer, but hardly a top-notch one.

Etudes presents itself as a quickie course in the classical ballet vocabulary and its two major nineteenth-century styles, but it’s really a shameless showpiece—hokey and thrilling by turns, like the carnival rides at Tivoli, Copenhagen’s famous amusement park. It opens with a line-up of women—lighted dramatically to emphasize their svelte and muscular legs and feet—executing a picturesque version of the daily exercises at the barre that develop the classical dancer’s exotic anatomy. It proceeds through passages—disconcertingly detached from specific narrative—in both the gauzy, evocative Romantic mode (think La Sylphide and Giselle) and the brilliant, objective Classical mode (think Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty). It climaxes in a pull-out-all-stops exhibition of gyroscopic turns, vertical jumps adorned with small, throbbing beats of the feet, and huge cross-stage leaps at high speed on interlacing diagonal paths—this last tour de force resembling nothing so much as a traffic accident waiting to happen. While highbrow ballet aficionados love to despise the cheap exhibitionism of Etudes and its kitsch sentiments, it’s a perennial crowd pleaser, performed all over the world. It speaks to the general public’s need to understand ballet dancing as something at once heroically athletic and unfathomably beautiful.

The RDB’s current production was mounted last year by the former Paris Opera ballerina Josette Amiel. She was in town again this season to coach the present crew of dancers and she made them look marvelous. At its best, traditional Danish style produces a pearly glow; Paris Opera style typically creates a diamond-like effect, all precision and dazzle. Under Amiel’s direction, the two approaches were happily combined. The Danish dancers performed at the height of their technical capacity (which, on the average, is not world-class), on a larger, bolder scale than is their norm—without forsaking the graciousness that makes them universally appealing. The two casts I saw of the three leading roles—a ballerina and a pair of cavaliers—revealed the limitations of the company’s modest talent pool. Yet Caroline Cavallo’s musicality was memorable, as was the lush fluency of Andrew Bowman, dancing as if impelled by joy.

The RDB will be in Washington, D.C., at the Kennedy Center January 13-18, 2004, performing La Sylphide and Etudes along with Napoli, the Bournonville ballet generally thought of as its trademark. The engagement will give an audience far from Denmark the chance to see the only company among ballet’s Big Six (the others being American Ballet Theatre and the Kirov, Bolshoi, Paris Opera, and New York City Ballets) that has achieved its status without putting bravura technique first. Not coincidentally, the Danish company is the one that’s almost impossible to encounter without falling in love.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias