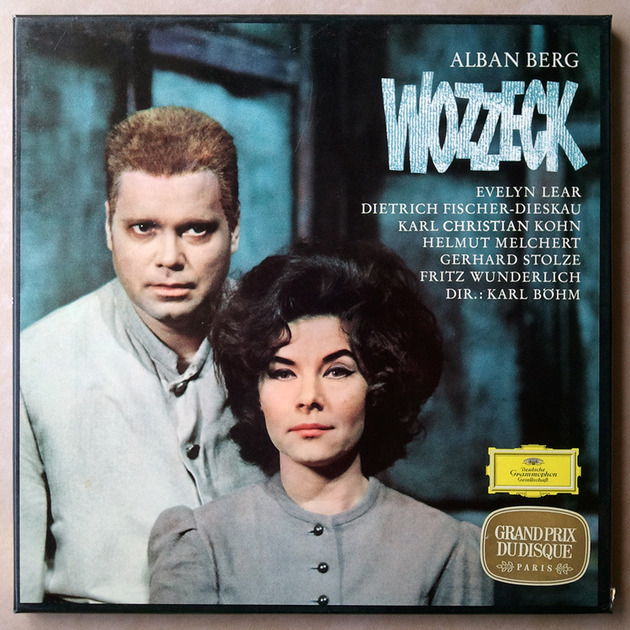

It was, without doubt, the frightening photo of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Evelyn Lear on the Deutsche Grammophon boxed vinyl recording of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck that first attracted me to this modern masterpiece. The cover promised whatever was contained inside was bound to be completely different. I was still an undergraduate music student at the time, and I’d had the pleasure of meeting Karl Böhm, conductor on the recording, when The Hartt School gave him an honorary doctorate degree. If Böhm was involved, it had to be something serious.

Witnessing Wozzeck in the privacy of one of the school’s music library listening rooms was similar to hearing Einstein on the Beach for the first time, as crazy as that sounds. Both operas were unlike anything else I’d ever heard and both left me with an exhilarating sense of groundlessness. In Wozzeck, I became pre-occupied with the passacaglia variations in the fourth scene of Act I, which centers on Wozzeck and the self-interested, maniacal Herr Doktor. The scene raises the matter of who is more insane, scientist or subject. Â

I’d studied German in high school and I was studying it again in college. I read the fragments of Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck in German, and remarked at how the music had a kind of kaleidoscope effect on the text. During this period, I noted as well that in Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach, the compositional structure was audible. In Berg’s Wozzeck, however, the score had to be studied and analyzed. I couldn’t “hear†its structure necessarily, but admired it all the same. In terms of the emotions, Einstein was a “bright†piece, while Wozzeck was disturbing and hopeless. “When nature ends, and the world gets so dark,” as Wozzeck says in the first act, made that clear from the outset.

As I have asserted before in this blog, artistic experiences are amplified as they mix with one’s personal experiences. As time went by, I never stopped thinking about the plight of Wozzeck. During my early years in Boston, I moonlighted as a research study subject, just as Wozzeck does in the opera. The research experiments I participated in were strange and sometimes upsetting, but they paid well, and always in cash. Once a pathologist painted my upper left arm with a poison ivy solution. A week later, when I had a full breakout, he paid me $600 for two punch biopsies of the bubbled skin, which took months to heal over. In another experiment, I went on a high-sodium diet for two weeks as a “healthy young control†in a geriatric study of cardiac function. I was required to save all of my urine in a gallon jug I carried with me in a backpack. And in yet another, the least invasive (at least physically), I wore EEG monitors for a couple hours while I read and explained the meaning of proverbs, for a study in the cognitive function of left-handed males. These experiments left me with some sense of what it means to serve another person’s career interests, which are often disguised as the vague desire to “help humanity.” And they make the Doctor’s experiments in Wozzeck with a legume-based diet and daily urinalysis seem tame by comparison.

I considered my long stint as a lab rat when Hans Graf conducted his farewell offering here in Houston: Berg’s Wozzeck in concert with the Houston Symphony. “It will remain in your memory forever. It will be one of the most important and exciting things I’ve done in my 12 years here,†Graf wrote in program notes. The Maestro was not mistaken. In the inferiority complex known as Houston, this might be the greatest musical offering I’ve witnessed since I moved to the city in 2010.

I say “inferiority complex,†because so many people here in Houston continue to think of the city as no competitor for New York, Boston, Chicago, or any of the other “great†American musical cities. Graf’s interpretation of Wozzeck is the finest I have ever witnessed, live or recorded, and stunning evidence that the city can hold its own as an artistic center. I haven’t heard the orchestra give such an inspired performance since Christoph Eschenbach’s conducting last season of the Mahler 5th.

Graf secured a dream cast, featuring Roman Trekel and Anne Schwanewilms as Wozzeck and Marie, Marc Molomot as the Captain, Nathan Berg as the Doctor, and Gordon Gietz as the Drum Major (full cast and creative team is available at the HSO website). Trekel and Schwanewilms didn’t have to “play†their roles as young and sexy. Both have a natural physical and vocal appeal and effortlessly project a sense of youthfulness. Previously, I had thought of the characters as foreshadowing the diminished qualities of middle age. Here, they were definitely interpreted as passionate and young, in sharp contrast to the Captain and Doctor, and more poignant in their hopelessness.

I’d thought the audience who had gathered to hear Graf’s farewell offering would start to walk once the unrelenting atonality of Wozzeck became evident, but I didn’t see one person leave. The audience was rapt for the evening. The opera was performed without any intermission.

Two main points are asserted by this stunning production in Houston. The first is that the opera does not require a lavish staging. I remember seeing it at the Metropolitan Opera, some years ago, immersed in red lighting. It was a heavy-handed and too-literal interpretation of the text. If the opera is well-acted and sung with conviction, costumes and sets are really a distraction. Here the blocking was kept very simple and the text translated with supertitles. The important thing is to get the full orchestra up on the stage, in view of the audience, for the orchestra is the most prominent character in the opera! The ancillary chamber orchestra, dance hall band, and cabaret players, all of whom play simultaneously (very Ives) with the orchestra as the story unfolds, need to be seen as well as heard.

The other point has to do with stance. Why offer Wozzeck to contemporary audiences? Graf’s deep feeling for the work has to do with his appreciation of its overwhelming embodiment of suffering. “The whole aim of the opera is to show compassion – to empathize with a poor man and a poor woman, who are prisoners of their fate and are driven to this catastrophic ending,†Graf wrote in his program notes. “You don’t blame anybody after this opera – neither Marie for being an adulterous wife, nor Wozzeck for murdering her. You just feel very deeply moved and sad, and I think this is a highly ethical thing. It invites you to contribute to a world which does not allow such a catastrophe.†Â

I directed scenes from WOYZECK in College that was thrilling and shocking for students in the 1970’s; later I heard rehersala for Abbado at LaScala in Ronconi’s production that were unforgettable. The Met, has done

Berg’s opera somewhat regularly over the years but noth renditions I saw were dull or rudely unimaginative,

as The Met can be w/MAHAGONNY as well. One of these days….maybe a shattering production in my mind.

the Wozzeck story is truly timeless. The characters archetypes. One would think this opens the script up to a wide variety of interpretation, but strangely enough the opposite has occurred. I hope you will pursue again in your work!

Excellent perspective…. Got me thinking about many issues.

Thanks so much for commenting. The performance here in Houston was brilliantly multi-layered. The main revelation was having the orchestra on the stage.