Now and then, from the deep, hidden river of life, great spirits in human form are thrown up,” Henry Miller wrote in 1956. Like semaphores in the night they warn of danger ahead,” he continues. The phrase is from The Time of Assassins and refers to the French poet Arthur Rimbaud.

On a hot Sunday afternoon I had this particular book, along with my journal, tucked under my arm when I returned to Houston’s Station Museum of Contemporary Art to re-examine Witness to War: George Gittoes. I’d been at the opening of the show, but really only skimmed the Australian-born artist’s work.

A new show in Houston is always an excuse for a big party. Food trucks, complimentary beverages, and live music are de rigueur. This opening was no exception, even if the lively mood of the crowd stood in odd contrast to the horrors depicted in the paintings, drawings, installations, sculpture and video. Half of a woman’s face sliced off by a machete. A boy learning how to behead an infidel. Nobody seemed to regard the notice on the door stating that some of the disturbing images were unsuitable for children.

On this particular Sunday, I spent nearly two hours alone in the gallery, until I ran into Gittoes setting up his camera next to one of his installations. What followed was a useful discussion and personal tour by the artist, for me an unforgettable experience. Gittoes strikes me as one of the semaphores” Miller indicated more than half a century ago. I have no doubt that he is a true genius, but I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

It was at another opening, the Stanley VanDerBeek retrospective at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, where I first met Gittoes. I’d hoped to write about both shows in the same blog, since VanDerBeek seemed to capture in his wonderful multi-media work certain aspects of the collective American mindset around potential nuclear war. I thought I could make some clever connection between the two artists. I’ll write about VanDerBeek here, but I’ve decided to do so in a separate column. Gittoes is a different brand of visionary, primarily because he’s been at the front lines of nearly every significant war that’s unfolded over the past four decades.

This might be why his extraordinary blue eyes have such a feeling of post-traumatic weariness. His epic Night Vision” diaries shown in Houston document his profound experiences in places like Cambodia, Rwanda, Nicaragua, Northern Ireland, Philippines, Bosnia, East Timor, Palestine, Congo, South Africa, Lebanon, Chechnya, Western Sahara, Yemen, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iraq. He is spellbinding, to say the least. I am both afraid of him and also worried about his physical safety. His work tends to piss off a lot of people.

I’ll admit that I was scared to return to the Station Museum. I’ve had this feeling of apprehension before, in galleries as well as performance halls, but I’ve learned to proceed anyway. I went alone because I prefer to deal with these emotions by myself, and also because it becomes necessary for me to write in such situations, and that’s difficult for any companion to endure. Some of the artists, musicians, and choreographers who have terrified me over the years include Pina Bausch, Mike Kelley, Bill T. Jones, Tony Oursler, Glenn Branca, Jasmin Vardimon, and Martin Creed. I write about them in order to understand my visceral reactions to their work.

One of Creed’s recent installations at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, for example, practically gave me a panic attack. Viewers were invited to enter a large room chock-solid with gold balloons. The smell of latex and the sound of children’s voices (real ones, exploring the room with parents), combined with the claustrophobic space, made for a truly nightmarish experience. I emerged nauseous and couldn’t even recover in the museum gift shop, where I thought a little souvenir shopping might soothe me.

Gift-shop syndrome. Even intelligent persons fall for it. The epitome, I think, came earlier this year at Houston Grand Opera, when my partner noticed Dead Man Walking T-shirts in kid’s sizes. Somehow, that seemed worse than a coffee mug or umbrella decorated with Monet’s water lilies.

There isn’t a gift-shop problem at the Station Museum. With the exception of a few books on Gittoes and some copies of his seminal film on the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Soundtrack to War, there isn’t anything to buy, nowhere to escape for a moment from the exhibit. When I asked about his relationship with dealers and collectors, he replied matter-of-factly, “Nobody buys my work. Everyone says how much they like it, but they never buy it.”

Gittoes makes me consider what is true in art, and what is propaganda. The latter is easy to make and sell. Propaganda usually involves a certain quality of sentimentality, as well. Norman Rockwell on America, for example. Truth, especially in abstract work, is complicated. Before we can determine whether or not art is true, the meaning of the word must be determined. When Mr. Gittoes and I discussed this, I offered one Buddhist definition of truth: a situation in which there is no deception. Later, Gittoes said, “I am a mystic, which is what makes all of this different from social realism.”

We stood talking in between his installation of a mosque and another of a DVD store. He wanted to install a dress shop in the museum as well, because these are the three things the Taliban seeks to destroy, at least in northwestern Pakistan. On the floor next to the mosque Gittoes has placed iron arabic letters arranged in the phrase, ‘The martyrs rise to paradise through the blood of the innocents.”

What’s missing from this photo of the mosque is a curious sculpture, which looked other-worldly to me, perhaps some kind of pacifying force. When I asked about it, Gittoes called it a fourth-dimensional shape. “I invented it as a mathematician. I love Islamic mathematics, pure geometry. It was my final minimalist work,” he said, adding, “I wanted something inexplicable in there.”

Resonating with my experience of the Gittoes retrospective (the first major exhibit of his work in the U.S.) is Ft. Worth Opera’s recent stunning production of Philip Glass and Allen Ginsberg’s Hydrogen Jukebox, which premiered 21 years ago at the Spoleto Festival in South Carolina. There is nothing old-fashioned about the opera, however, which integrates poetry spanning Ginsberg’s career with a heartfelt score by Glass. The fact that it was sung by an outstanding cast of young artists (many of whom were likely born just around the time the opera premiered) makes it feel even more up-to-date.

Ginsberg has said that the “secret message” of this collaboration was “to relieve human suffering by communicating some kind of enlightened awareness.” This aim seems very much like that of Gittoes. I would add that all three artists present their work in a highly stylized “language” (in the greater sense of that word) that is entirely free of deception. In this way, it is true art.

Hydrogen Jukebox presents the political and the personal at once, and much of it is quite controversial, at least for those of a more conservative mindset. If Walt Whitman sang the body electric, Ginsberg shouted it from the rooftop of America, and I’ve never stopped applauding him. During my youth, I never thought America would enter into such a shockingly pro-war period. The past several years, I’ve listened to all the tired rhetoric about how our troops are “protecting our freedom,” for example, as they invaded Iraq and Afghanistan. And this kind of thinking is, for me, the worst sort of intentional deception.

During the performance in Ft. Worth I realized it was also the first time I ‘ve witnessed on the operatic stage gay characters engaged in erotic encounters who are happy, rather than creepy and filled with self-loathing. In Houston, we’ve had plenty of scary pedophiles à la Benjamin Britten (Peter Grimes, The Turn of the Screw) at Houston Grand Opera for the past two seasons, so Ginsberg and Glass in Ft. Worth were more than a welcome relief. I haven’t seen Stewart Wallace and Michael Korie’s 3-act Harvey Milk, which premiered at HGO in 1995, so I can’t speak to the representation of gay men in that work, but I’ve heard it’s favorable. Such positive portrayals are precious, and the young men in this production did a stellar job, giving these characters (Ginsberg and his life-partner Peter Orlovsky) dignity and complexity. It was so much more sophisticated than Aaron Tveit and James Franco’s ridiculously sentimental interpretations of the same men in Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman’s hokey Howl, released last year. This is what I call the cute-ification of modernity in the film industry. Other fine examples of this disturbing trend exist in Julie Taymor’s awful Frida and Agnieszka Holland’s dreadful Total Eclipse, starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Rimbaud.

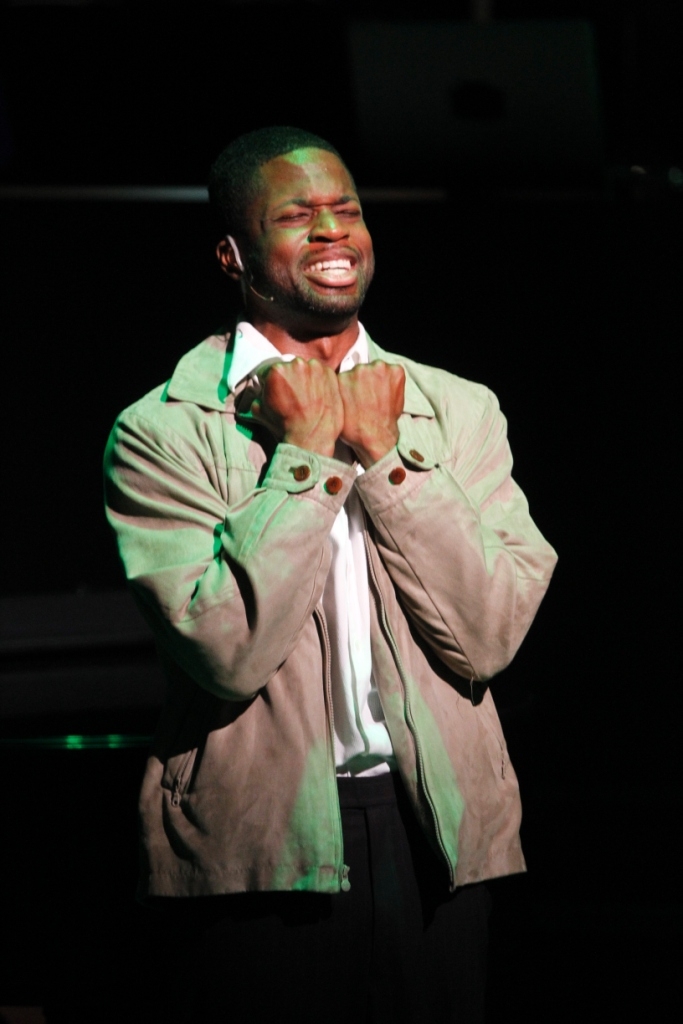

One of the most emotionally-charged moments was the recitation of Ginsberg’s seminal 1966 Wichita Vortex Sutra, which comes at the end of the first act. Talented Justin Hopkins sat on the edge of the piano lid, legs dangling, to deliver this lengthy masterpiece. Nothing but the piano accompaniment to support his “singing,” it was nonetheless a theatrical miracle. The poem is filled with the kind of performative utterances we need today more than ever: “I lift my voice aloud, make Mantra of American language now, I here declare the end of the War!”

Dear Tedd,

Thanks for your cogent musings on these artists who are unafraid of our harshest realities. Wish there were more! Somehow we are trying very hard to find a voice or a dance or a story etc. which can allow us to face the pain. Keep at it and I will too. Kathy

Thanks so much for reading. Ginsberg’s poem, 45 years later, is startingly apt for our present time. Here’s another brief excerpt from the final section:

“Let the States tremble,

let the Nation weep,

let Congress legislate its own delight

let the President execute his own desire—

this Act done by my own voice,

nameless Mystery—

published to my own senses,

blissfully received by my own form

approved with pleasure by my sensations

manifestation of my very thought

accomplished in my own imagination

all realms within my consciousness fulfilled

60 miles from Wichita

near El Dorado,

The Golden One,

in chill earthly mist

houseless brown farmland plains rolling heavenward

in every direction

one midwinter afternoon Sunday called the day of the Lord—

Pure Spring Water gathered in one tower

where Florence is

set on a hill,

stop for tea & gas”

HI:

Just letting you know I read your article. I am writing a libretto at the moment and very interested in these operas you mentioned here.

Gene Elder

Archives Director

HAPPY Foundation

411 Bonham, by the Alamo

San Antonio, Texas, 78205

210 732-3238

elder4tomato@yahoo.com

“Art, like the Alamo, has to draw the line somewhere.” –Gene Elder

Thank you for writing such a profoundly honest and powerful consideration of Gittoes’ work.

Wow. This was fantastic. I have to run to the Station and the CAMH asap.

Houston seems a long way behind, having returned to Afghanistan ,so it was wonderful to be sent this review. It is a one of the rare pleasures to speak with someone who knows, with such depth and feeling ,the traditions of poetry , music and art . Theodore looked around my show and said he could see Arthur Rimbaud. This was an amazingly accurate perception . I have carried Rimbaud with me everywhere I have travelled since discovering him at about 14. Season in Hell remains all the wars.

I met Ginsberg and performed with him in a most unlikely place , Adelaide , South Australia at the first Adelaide Arts Festival in 1971. Ginsberg turned the Clear Water Cafe into his own salon. I had brought a small circus of clowns and mime artists from Sydney’s experimental arts commune, the Yellow House. My troupe were performing Sufi dances. Whirling on one of the festival stages when Allen spontaneously joined in. We then became friends and shared our love of Rumi and Sufi poetry.Houston has been a time of completing the circles and Theodore’s relinking with Ginsberg is another one. Thanks Theo. George Gittoes