Seven years ago in Toronto, at a Kalachakra initiation given by H.H. The 14th Dalai Lama, I saw secular Tibetan dancing for the first time. Of course, I saw much “devotional†dancing there as well, if that’s the right term. Â

The preparations for this important Buddhist ritual require at least a week of effort from hundreds of people. In addition to creating an intricate sand mandala, the lamas perform Dance of the Earth, which pacifies invading spirits and helps establish a proper mindset for participants. It is epic, filled with many symbolic gestures, difficult for an American to decipher or even to discern. The lamas need considerable strength to finish, and often they are exhausted when it’s over.

In Toronto, the local Tibetan community wanted to offer His Holiness a secular dance as well, as another way of expressing gratitude. As the lamas continued with the ritual dance, a long serpentine procession of Tibetans (men and women in separate lines) surrounded the sacred space, chanting another melody and wearing traditional silk brocade outfits. They were loud, clapping, very cheerful, some with drums. It was fascinating to see these two dances collide, with none of the participants on either side minding one bit. Some Westerners regard dancing solely as an entertainment, but Kalachakra is not entertainment, it is ritual. I never forgot this incident, so spontaneous and so reminiscent of Cage and Cunningham’s parallel pursuits. The two musical events running simultaneously were like an Ives symphony. Seven years later, I can still hear them in my head.Â

Over the years, Buddhism has taken me on some fascinating ancillary paths. For several years I studied the dharma art practices of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a Tibetan lama who came to the West in the early 1960s. In writings he lamented what he felt was the absence of secular art forms in traditional Tibetan culture. Trungpa became quite taken with Japanese “Zen†art, often promoting the study of ikebana, calligraphy, and archery at the numerous meditation centers he founded around the world. His experience as a young man with traditional lama dancing contributed to his later development of something he called “Maitri Space Awareness,†as well as the founding of his own performance ensemble, Mudra Theater Group. As I understand him, Trungpa toggled between Buddhism and secularity in his theater exercises and dance. His work could be seen as a first-step synthesis of Tibetan traditions and Western theatrical modernity.

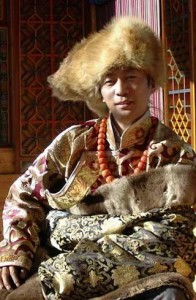

This past weekend, Houston’s celebrated Dance Salad Festival featured the work of Sang Jijia, a Tibetan choreographer who appears to be in his mid-30s. Tall and handsome, his long hair tied back, he looked contemporary and mysterious at the festival, differently than he does in the picture above. This is the first time I’ve seen a young Tibetan choreographer who isn’t working overtly within Buddhist tradition. Well, at least it doesn’t appear that way. The Buddhist mindset flavors his work even if it isn’t immediately evident.

Sang Jijia’s dances have intriguing up-to-date names, such as Happening Continuous and 365 Ways of Doing and Undoing Orientalism. For his 2007 solo Snow, he even had a score by Flemish Belgian composer Wim Mertens.

In Houston, Beijing Lei Dong Tian Xia Modern Dance Company offered his stunning Standing Before Darkness, a large ensemble piece with a sampled electronic score by Dickson Lee and  featuring a stage strewn with white plastic chairs. In my review of the performance for Houston Chronicle (see sidebar), I compared Sang Jijia’s choreography to that of Forsythe’s, in particular his One Flat Thing, Reproduced. This is always the problem for critics, though. We love to discover an influence and then we love to show how clever we are for making the connection.

In Houston, Beijing Lei Dong Tian Xia Modern Dance Company offered his stunning Standing Before Darkness, a large ensemble piece with a sampled electronic score by Dickson Lee and  featuring a stage strewn with white plastic chairs. In my review of the performance for Houston Chronicle (see sidebar), I compared Sang Jijia’s choreography to that of Forsythe’s, in particular his One Flat Thing, Reproduced. This is always the problem for critics, though. We love to discover an influence and then we love to show how clever we are for making the connection.

These two dances are related because they are both abstract spectacles, and because they share the kind of similarly emphatic, “crazy” modern style often associated with Forsythe. I watched Jijia’s dance three nights in a row, with increasing interest. A few days later, I’m wondering about the artistic children of Forsythe. So many of them have made impressive careers on their own, employing his far-reaching strategies but within their own original aesthetic. Crystal Pite, whose choreography was just presented in Houston by Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet, is a good example. Helen Pickett is yet another. Jijia certainly belongs to this prestigious group, and his Tibetan heritage and association with contemporary Chinese companies (he danced from 1993 to 1998 with Guangdong Modern Dance Company) make him unlike any Western choreographer.  Â

This draws us to the question of masters. For years following Balanchine’s death, I listened to dance critics speculate about who would follow in his path. What we’ve had is really more like a series of cheap imitations and no true successor. What about the living? Forsythe’s collaboration with Dutch composer Thom Willems has been, in my estimation, as important as that of Balanchine and Stravinsky. It’s not discussed much in America, since we haven’t seen very much of their work staged here. And if anyone has created a situation in which choreographers flourish and develop, it is Forsythe.

Another thing I heard for years: New York is no longer the center of international contemporary dance. American dance critics have been looking to London, Paris, Brussels, Berlin, Wuppertal and other European cities for at least two decades to learn about the newest of the new. We might want to consider Beijing, however. The Buddhist maxim, “everything changes,” is apt.

Last year during an informal teaching in Dallas, Tibetan Lama Dudjom Dorjee said to his students, “you clean your house, you clean your clothes, why don’t you clean your mind?” Sang Jijia’s choreography appears to be an attempt to clean the mind-of the viewer, the dancer, even the choreographer. In this way, it is Buddhist work.

Is Sang Jijia in fact Tibetan? (Ethnically, I mean.) The name doesn’t sound Tibetan; it sounds Han Chinese.

Perhaps he is, or his parents were, Han Chinese migrants to Tibet? Or perhaps he (as an ethnic Tibetan) had to take a Han Chinese name to be able to work in dance companies in the Chinese heartland?

Ideally, an artist’s ethnic background ought not matter much, of course. But in the context of Tibet and China today – i.e., the longstanding worry that Tibetan culture within Tibet will drown in a great sea of Han Chinese migrants – maybe it does matter.

In particular, Sang’s ethnicity could matter inasmuch as he is “a young Tibetan choreographer who isn’t working overtly within Buddhist tradition.” A young Han Chinese who grew up in the People’s Republic (even in Lhasa) would have a rather different relationship with Buddhist tradition than would a young ethnic Tibetan.

Thanks for making this important point. His bio in the festival program says: “Tibetan born in Gansu, Sang Jijia graduated from the Beijing Central University for Nationalities and was a dancer with Guangdong Modern Dance Company from 1993-1998.”

Fantastic, Tedd.

I love the connections you make here because the connections also serve to educate. I’ve never understood why Forsythe often seems so readily dismissed in the States. In any case, I look forward to seeing Sang Jijia’s choreography, but your review will tide me over for now! (I’m pretty sure I saw him perform with Guangdong years ago.)

In all respects, thanks very much for this!

–Renee

The interplay/influence of traditional ritual dance and contemporary work is always fascinating. Many contemporary choreographers are exploring Buddhist thought as both process and aesthetic in secular works. Meredith Monk certainly comes to mind. This is a direction that my work has been exploring in the last few years also.

I’m sure you have seen Thierry de Mey’s amazing film, “One Flat Thing Reproduced.” Not pure documentation, it is a re-imagining of the Forsythe work in a particular site for the cinematic medium.

Thanks for the article, Tedd.