Every so often, a pianist comes along who changes my life. This happened in D.C., when I listened to Peter Serkin juxtapose Beethoven and Stefan Wolpe. It happened one night in a faded Victorian living room in Hartford, when Edmund Niemann played John Adams’ Phrygian Gates, only a few years after the piece had premiered in San Francisco. It certainly was the case for me when Barenboim played the late Beethoven sonatas. And it happened again last night in Houston, when Jeremy Denk realized Charles Ives’ first and second piano sonatas.

Fresh from an impromptu concert Sunday afternoon at Carnegie Hall, his first solo recital there (he filled in at the last minute for an ill Maurizio Pollini), Denk didn’t seem the least bit jet-lagged. On Monday in the New York Times, Anthony Tommasini aptly characterized him as an “adventurous pianist with boundless enthusiasm and stamina.” I think of him in the way folks used to think of David Tudor, namely, as an entirely versatile pianist capable of realizing any score without condition.

Denk’ s performance was presented by Da Camera of Houston  in the main entryway of The Menil Collection, a spacious if not austere gallery with white walls and black wood floors. The piano stood on a short platform just in front of Clyfford Still’s Untitled 1955-6, a large abstract-expressionist painting in dark red, black, and white oil with a dash of rust at the top  and some thin swipes of bright blue down the middle of the black pigment. The Ives piano sonatas went well in this setting,  invoking the behemoth in Still’s canvas. The concert was sold-out.

I admire the way Houstonians gather naturally to listen to great music, without pretension and with a receptive spirit. Denk spoke informally to the crowd before each of the sonatas, sharing a few anecdotes and playing excerpts. He is often a funny guy, and one feels instantly comfortable in his presence.

Once the gagantuan Sonata No. 1 was underway, however, the concert became a more complicated experience. Of course, I was stunned by Denk’s command of technique. But great pianists take us far beyond considerations of expertise, into a world of memories, reflections, shocking confrontations and desires. His reading of Ives is nearly cinematic, wide-ranging in color and dynamics, at times even terrifying. I felt transported to another planet, until I realized that, actually, Denk had taken me back home.

The Sonata No. 1 is music that evokes archetypal Connecticut, where I was born and grew up. The work’s more emphatic, multi-layered sections transported me to the cavernous music store of my childhood, Gallup & Alfred on Asylum Street in Hartford, where folks shopped for pianos in the basement, records and sheet music on the first floor. It was a dusty, slightly disorganized hub of activity. It’s also a kind of place that has nearly disappeared in America. Â

What ever happened to music stores? I’ll admit that I’ve been buying sheet music online for almost 20 years now. I don’t even remember the last time that I was inside an actual store that sold printed piano scores.

Getting music via the web is mostly a good thing, of course. It’s allowed me to order scores directly from Japan, Argentina, France, Germany, Holland and England and the prices aren’t bad. But I do miss the stores of my childhood and adolescence, in Hartford and New York, with composers’ busts in the windows, and where you could sit down at a piano and play the music before purchasing it. Or you would run into somebody you know, or see a local celebrity, a conductor or violinist from the symphony, for example.

When my mother and I weren’t shopping for new piano scores at Gallup & Alfred, we looked for used music at flea markets, tag sales and auctions. More often, it was hunting through the racks and boxes that provided the most excitement, anyway. “Look at these little piano pieces by D’Indy,” I’d say to my mother, hoping that she would agree that the price was reasonable. She rarely refused me a book of music.

As I browse through my piano music library here in Houston, it strikes me that more than half of my collection is second-hand. I particularly remember one box, which my father obtained at auction for almost nothing, and which represented a thorough survey of the piano repertory. Mother and I were thrilled when he returned home with it one night. Some ancillary notes and papers in the box indicated the former owner’s name, a guy  named Paul.

It’s possible that Paul had some kind of psychological instability, perhaps an obsessive-compulsive disorder. Maybe he was recovering from a mental breakdown. Most of his scores turned out to be  useless, because they had been heavily annotated in red and blue ballpoint pen. Maybe “annotated†isn’t quite the right word. In some of the music, Paul had written the name of the letter next to each and every note, making the staves nearly impossible to read. He underlined every word, often providing the English translation, as well as every pedal marking and all the dynamics. To what purpose? It must have taken him years to complete this seemingly futile activity.

Along with the music, there was a souvenir book from the Metropolitan Opera  in which Paul had carefully removed with an X-acto knife all the photos of African-American singers. Leontyne Price, Grace Bumbry, and Shirley Verrett had disappeared under his careful hand. Either this meant that these singers were distasteful to Paul, or instead that he had made a lovely collage celebrating them. I like to imagine that it was the latter. Â

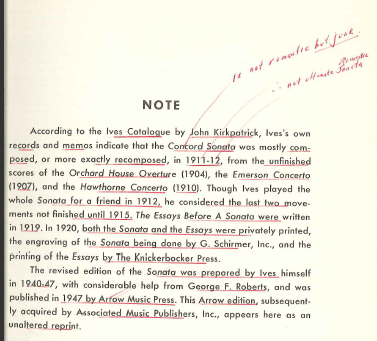

Occasionally Paul comments on aesthetic matters. On the inside cover page of Charles Ives’ Concord Sonata, for example, he’s written, “is not romantic but junk.†

And apparently Paul didn’t think too highly of the Concord Sonata, because he never filled in all the note names. He had only completed his standard underlining up to page 5. I imagine that the lack of bar lines drove him crazy. This was good for me, however, since the score is still mostly readable and therefore playable, and the original price ($8.00, it sells now for $24.00), was about what my father paid for the whole box. There was also a book of Scriabin etudes, autographed by Ruth Laredo, which were untouched, and I certainly didn’t part with those.

I tucked the slightly yellowing, partially annotated Concord Sonata score  under my arm last night as I headed to the Menil Collection to hear Denk.

While Denk used a score for Sonata No. 1, I was incredulous when he sat down and played the Concord entirely from memory. In his introduction the latter, he told us it was alright to laugh during the second Hawthorne “scherzo” movement. I found myself laughing as the section climbed from one extraordinary eccentricity to the next. And as themes fought with each other, vying for attention from both the pianist and the listeners, I remembered the piano store on Asylum Street, with its cacophony and smell of cigar smoke.

The Proustian comparison is trite, I know, but when it happens in an authentic way, as it did last night in Houston, the triteness doesn’t diminish the power. When it was over, I stepped out into the foggy night and watched bats scurrying over the Menil Collection lawn. I got in the car, and after starting the engine, Peter Gabriel came on the radio.

“I was feeling part of the scenery

I walked right out of the machinery

My heart going boom boom boom,” he sang.

Thanks so much for this terrific post! It resonated with me in so many ways. I heard Jeremy last season at the Ojai Festival, where he played a Sunday morning recital of the Ives’ 2nd Sonata and the Goldberg Variations, all from memory. His relaxed, comfortable manner at the piano was evident in both his speaking about and demonstration of both works, as well as his playing.

In my hometown of Pratt, Kansas, there was a furniture store that had a small side business of piano sales, instrument repair, and sheet music sales. I bought my copy of the G. Schirmer edition, hardbound, of The Marriage of Figaro, as well as so many other things. I live in Los Angeles now, and Old Town Music in Pasadena is one of my favorite places to shop. They carry a lot of varied materials, from books on music, to full scores and sets of parts, as well as instrument repair and assorted what-not.

Thanks again for reminding me of both of those experiences. You’re exactly correct – these kinds of things are what make up the entirety of Proust’s work.