Last month I had the opportunity to spend a couple of days with senior educators from Interlochen Center for the Arts, where I am a board member. We were doing a deep dive into the ways teaching and learning are changing, given the immediate availability of information and ideas via digital devices in the classroom.

Last month I had the opportunity to spend a couple of days with senior educators from Interlochen Center for the Arts, where I am a board member. We were doing a deep dive into the ways teaching and learning are changing, given the immediate availability of information and ideas via digital devices in the classroom.

I am not an expert in educational theory, having never taken a class or read very much about how teachers learn to teach.   But I have been fortunate to have been on the receiving end of memorable teaching from a handful of great teachers who made their classes pure joy and who made a lifelong imprint on me. After the Interlochen meeting I got to thinking about this because personally I associate great teaching with great presenting, with  teachers who used a lecture-based format to bring their subject matter to life with intensity, clarity, and passion.

Now it looks like my ideas about great teaching are outdated. And it isn’t just me who needs to make the adjustment. Educational institutions are training new teachers, or re-training teachers “of a certain age,” to take advantage of digital tools and to evolve their teaching styles based on the idea that the best teachers are not “the sage on the stage” but rather act as “the guide at the side.”  In fact if you put that phrase into Google, you’ll get a few million hits, explaining that the “transmittal” method of teaching is increasingly unhelpful (the teacher knows something that the student does not, and his/her job is to transmit it to the class) because it won’t prepare people for the lives they will need to lead in the future (particularly since we expect the rate of change to increase).  Instead, we need to help students learn to teach themselves throughout their lifetimes.  The underlying premise is that information is readily available, but knowledge must be constructed by the individual. And this is best nurtured through inquiry-based teaching methods.  The teacher’s job is not to impart information but to create the context within which students discover what is important to be known. Questions, games, or “challenges” are designed to facilitate discovery, and the teacher is the resource for problem-solving, not the one with the Answer Key.

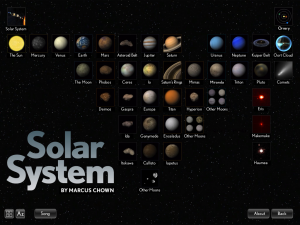

Debates about the best teaching methods have been going on for a long time (centuries) and would not be particularly noteworthy, except that with the advent of portable computing devices, the ability to discover information has never been easier. As classrooms move to “one to one” computing (each student has her own untethered device), teaching methods can be device-powered in new ways. Apps that support inquiry-based classroom education are proliferating, making education more easily self-directed and rendering printed textbooks obsolete. (Check out, for example, the beautiful educational apps from Touch Press, including the Solar System app pictured above.)  Teachers can use these tools to power student learning, but their styles and methods need to evolve.

Assuming these trends in education are pervasive and increasing,  the next generation of graduates will expect to interact in new ways not only in their workplaces, but also in our theaters, museums, and concert halls.  In the workplace, people will have greater expectations for independent and team-based problem-solving, and will be comfortable working with minimal hierarchical supervisory structures.  In other words, bosses who are bossy will need to adjust their styles. This trend is already underway, and seems favorable for employee engagement and for making work interesting and fun.

In terms of audience and community engagement, audiences will expect us to offer them a meaningful role within more open systems of curation and presentation (asking our organizations to behave more like the guide and less like the sage). Cultural groups that today are experimenting with ways of giving the audience a voice in their artistic projects are on the right track. Projects like the Walker Art Center’s Open Field project, Spring for Music’s Fantasy Program Contest, or philanthropic sites that let the public help decide which works to commission through online donations (check out the London Sinfonietta’s Sinfonietta Shorts program, one of many such examples) — all these are inspired by digital tools and the engagement possibilities that they enable.  Organizations that continue to practice rigid or cloistered decision-making will lose out on the benefits that audience engagement will bring to the mix.  It will be interesting to see how this plays out in the next decade or so, and to see how the nonprofit cultural sector learns to take advantage of changed expectations.  Do you have any examples to share?