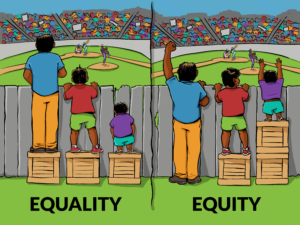

Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire

Thinking about orchestras and equity, two things have helped me frame a perspective: Angus Maguire’s reboot of Craig Froehle’s graphic (featured above) and Createquity’s article Making Sense of Cultural Equity.

The Maguire/Froehle graphic is well known for good reason. With a simple image it explains a complex idea: that equality doesn’t necessarily achieve equity. For a great piece about this graphic, its shortcomings and non profit arts funding, check out this blog post (full disclosure/shout out: it’s by my brother, Justin)

The Createquity article defines four visions for cultural equity:

- Diversity: mainstream institutions become more diverse and reflective of their communities.

- Prosperity: large budget organizations focused on artists of color present work to a broad audience.

- Redistribution: funders provide more resources to organizations rooted in communities of color.

- Self determination: people of color have ownership over shaping cultural life in their communities.

I wanted to better understand what these visions would mean for orchestras. To help me with that, I took each of Createquity’s frameworks and tried to figure out: using the different visions to look at the Maguire graphic, how would I ‘cast’ the graphic and where would I locate orchestras?

(One note: in the graphic there is an equitably resourced figure (the middle figure) who’s resources don’t change between panels one and two; in these scenarios I’ve not cast anyone in that role. Also, I use the phrase ‘classical orchestra complex’ – by this I mean the network of schools of music, orchestras and funders that enable us to have professional American orchestras.)

Under diversity I would cast the predominantly white classical orchestra complex as the tall figure. Aspiring black and brown orchestral musicians are cast as the short figure. The baseball game then, are our professional American orchestra activities as they are today. Between panel one and two some of the resources (‘the box’) that support the classical orchestra complex relocates. Aspiring black and brown musicians get the resources and support they need to participate in professional American orchestras. Pretty straightforward.

Prosperity is cast similarly: the tall figure is played by the predominantly white classical orchestral complex; black and brown classical orchestral institutions and organizations (rather than individuals) are cast as the short figure. The baseball game is, as before, the work of professional orchestras. In the first panel, participation in those activities are dominated by the tall figure. Between panels one and two, some of the classical orchestral complex’s resources relocate to support black and brown classical orchestral institutions and organizations. This leads to professional black and brown classical orchestral institutions and organizations participating significantly more in the nation’s professional orchestral activities. Still pretty straightforward.

However, with redistribution and self determination it was harder to locate orchestras within the Maguire graphic. Right off the bat I realized that, under these visions, orchestras can’t be the baseball game – the thing everyone is trying to see. Instead, I had to see the baseball game as the people that art music performs for, engages and serves. Getting to ‘see over the fence’ would be akin to getting your work in front of an audience. The tall figure then, is the status quo which privileges large budget, European art forms (a status quo of which orchestras are a part) while the short figure became individuals, groups and art forms that have been marginalized.

So, what did I learn with from this exercise?

Not surprisingly, I see progressively more disruption for orchestras as the vision for cultural equity moves from diversity towards self determination. I think this tracks with the increasingly less central, controlling role orchestras play in the Maguire graphic as we move through the frameworks. In this regard, it makes sense that a diversity framework would be the framework most embraced by the field – it’s the least disruptive. Lord knows, orchestras don’t want any more disruption than they’ve already got. I get that on a personal level.

But the degree of disruption caused to orchestras can’t be the only thing we consider as we chart a more equitable path forward. In fact, it’s worth asking: should the level of disruption to orchestras be part of how we determine what vision of equity we embrace?

Beyond that, I think its simply not practical to think that other folks in the mix care about what level of disruption suits orchestras. Given all that, I tried to consider the disruption from an assets based perspective: what might we, as a field, gain from the more disruptive visions of equity?

One thing: we might get to see what happens when things we value – like musical athleticism – are put in service of different goals and how that opens up new spaces for the practice and the art form.

For instance: what happens when artistic quality is defined differently – like, if how engaged an orchestra were with its community, or how much art helps people connect, were weighted more heavily? What happens when those things become the goal and things like virtuosity are put in service of that?

What happens when content isn’t king?

(For more on this, look here for a great podcast about how connection rather than content is king.)

Sistema in Venezuela provides some striking examples for social change through music that might apply to the theme of disruption. Sistema works in Venezuela because it is culturally isomorphic with the spirit of revolution that imbues the country. Orchestral culture has piggy-backed on a larger, very vibrant social movement .

That it is why Sistema-like systems in the USA aren’t having nearly the same effect. Far from being connected to a sense of revolution, they are placed in the context of ghettos that have faced political and social stagnation for decades. There’s a sense of hopelessness, that nothing is going to change.

Instead of revolutionary zeal, we see another project of rich, white, do-gooders who will not even consider the systemic transformations needed to bring an end to our soul-destroying racist, economic class system. No revolution, no significant change in orchestras.

So is it really true that orchestras can only deeply change when they are a manifestation of larger reforms taking place in society as a whole? I think of Philadelphia which has 180,000 people living in deep poverty. That’s 12% of city, and equal to the entire population of Salt Lake City. That number includes about 60,000 children who face daily problems with hunger, to say nothing of their often dysfunctional families.

Even if we can work around the family problems, and the problems with hunger, how do we give the community a revolutionary spirit like Venezuela has, a very real sense that they are throwing off oppression and taking charge of their own destiny? Without that spirit, will youth orchestra be able to make meaningful changes?

Are the very things that might enliven the arts in America virtually forbidden because they would disrupt the social order? If you *genuinely* disrupt orchestras, which means disrupting the society that surrounds them, will it create ripples that are essentially forbidden, and with the result that those efforts will be crushed?

Shall we get rid of the plate of manure, or simply put an orchestral cherry on the top? Given the gravity of America’s social problems and the state of our cities, aren’t most of the proposals all these white folks are making about more diversity in the arts a bit naïve, if not downright candy-assed?

Whatever, I hope you will continue writing these blogs. It’s high time that orchestra musicians begin thinking a bit, especially if they dare to step out of classical music’s rows and columns and not march in step.