If you’ve been reading me for any length of time, you know I think classical music needs to modernize itself. Not that a lot of people don’t think that these days, but I’ve been pushing the thought for quite a while.

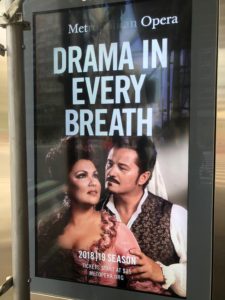

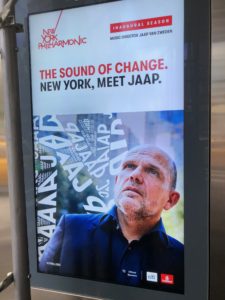

So you’d think I might love it when the Met Opera and the New York Philharmonic hyped their new seasons with these posters, done in the most up to date corporate marketing style:

But I don’t love it. To me these posters don’t, simply as advertising, do much to make their case. And they promise things that aren’t going to happen.

(I’m sorry, by the way, that I couldn’t photograph these from directly in front. There was something in the way.)

Start with the Met

“Drama in every breath!”Well, first, the photo on the poster doesn’t look dramatic. We’re seeing famous singers, who come off, in this poster, like models who are posing for no purpose except to look good.

And does the Met really give us drama with every breath onstage? I wouldn’t say so. This isn’t the Met’s best era. (See my wife Anne Midgette’s review of this season’s opening night.) And even years ago, when things were better, they didn’t offer every-breath drama.

Which is rare in opera anywhere. In my 50 years’ experience going to performances, I’d say opera is pretty much hit or miss. A few singers blaze, some light up intermittently, some just flicker. Some are perfect for their roles, in both looks and temperament, but some only meet the vocal requirements.

Sometimes there’s chemistry on stage, but often not, because the singers don’t really interact. Mostly they go their own way. (This is one big way that opera differs from film, TV, or spoken theater.)

At the end of the post, I’ll offer video examples, to demonstrate how undramatic opera even from the biggest stars can be. But for now, a story. Years ago, I took a friend to the Met who’d never been to an opera before. He was a composer in a style far from standard classical music, though since he had the personality of a romantic artist, he might have melted at the performance. If, that is, it really gave him drama in every breath.

The performance was of a production considered at the time one of the best the Met was doing, Boris Godunov, with Martti Talvela in the title role. And here’s how my friend reacted. Sometimes, he said, maybe 10% of the time, when the music and the staging came together, opera was the greatest thing in the world. But the other 90% was meaningless.

Maybe I’d give opera a higher score. 30 percent? But I haven’t seen drama in every breath. And I’d think anyone who goes to the Met expecting that will be disappointed.

As for the Philharmonic…

The sound of change!

The photo shows the Phil’s new music director, Jaap van Zwedeb. Aka a photo of their new music director, Jaap van Zweden. Looking, as someone I know said, like something out of Close Encounters. Like he’s in the Richard Dreyfuss role, looking to the sky for inspiration.

I get that they’re promoting him by his first name, just as the Philadelphia Orchestra has with their music director, who really seems to be exciting.

Maybe Jaap will also turn out to be first-name worthy. But does he really generate the sound of change? I don’t doubt that — under Deborah Borda, their new CEO — the Phil is changing, for instance by connecting with the liveliest part of New York’s new music scene. And their opening gala this year featured a new piece by Ashley Fure that (to judge from an excellent New York Times review by Anthony Tommasini) genuinely does seem different and arousing.

But even if Van Sweden (whom Borda didn’t hire) turns out to be terrific in New York, still he seems pretty much like a standard-issue conductor. So how will he produce the sound of change? Of course the orchestra will in some way sound different when he conducts, as it did with all its past music directors. But will a thrill surge through the audience, with people all but crying out, wow, the sound of change? Somehow I doubt that.

And so, it seems to me, reality again takes second place to hype.

Doing it right

Some people of course might say — maybe with a sigh of disapproval, but still taking these institutions’ side — that corporate marketing always pumps up the glitz.

But even the slickest corporate marketing can touch on truth, and that can be why it works. When McDonald’s says “I’m lovin’ it,” maybe I roll my eyes, knowing that they want us to eat unhealthy food. But they’re responding to a very real love that many people have for them, even as a guilty pleasure.

And remember Apple’s famous “Think different” campaign. So very slick, but grounded in reality. It launched in 1997, when Macs weren’t nearly as ubiquitous as they are now, and Apple didn’t yet rule the world.

So all they wanted was for us to think that Macs were different from PCs. Which they were. Anyone could feel the difference from the moment they turned a Mac on.

Video evidence: undramatic opera

- The Met Opera’s video teaser for this year’s opening night new production of Samson et Dalila. Using the “drama in every breath” slogan, and evidently filmed in rehearsal. Watch this without the sound, and it looks like a horror movie. Turn the sound on, and you hear Elina Garanča and Roberto Alagna yelling at each other. Which to me isn’t drama. It’s only yelling. To me this TV spot fails so much that Garanča and Alagna don’t even seem like they could be substantial people — let alone the big stars they are — in any field.

- “A te o cara” from Bellini’s I Puritani, live performance from Madrid, with Javier Camarena and Diana Damrau, two big stars. One of my favorite moments in all opera, and one of the hardest opera arias to sing. The tenor has to be both gentle and virile, soaring up to a high C sharp. Camarena sounds fabulous, and his appearance at least doesn’t contradict the hero he’s supposed to be. But Damrau! Her character is supposed to swoon so much for the tenor that she goes mad when later on he disappears. And what does she do here? She preens. I don’t see any interaction between her and the man who, at this moment in the opera, she can barely believe she’ll be allowed to marry.

- The famous duet from the Pearl Fishers, sung in concert by tenor Jonas Kaufmann and the late baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky. Huge stars, both of them, at the top of the opera totem pole. Hvorostovsky is truly dramatic, with the vision of the woman he’s singing about flooding into him from within. Kaufmann just emptily emotes. No meaning. He doesn’t seem to feel much. And there’s no contact between the two men. (The difference is so marked that when the two sing together, I can’t pay attention to Kaufmann, even though he has the melody, with high B flats that ought to soar. Hvorostovsky — as riveting vocally as he is visually — takes over my ears.)

What happens when opera truly is dramatic:

There’s a 1957 Italian film of Verdi’s Il Trovatore, with Mario del Monaco, Leyla Gencer, Ettore Bastianini, and Fedora Barbieri. del Monaco and Bastianini are so aroused you can’t believe their characters could be in the same room without wanting to kill each other. Which is exactly what the opera is about. And Barbieri seems deranged, murderous, and at the same time so crushed and miserable that I don’t know whether to hug her or run from her.. One of the most stunning — and real — opera performances ever.

Greg – As I understand your position, some great opera singers are also great actors, but most are only great singers. Unfortunately, that’s true. Also, unfortunately, not many great actors are also great singers. As for your friend who wasn’t very impressed by the Boris Godunov performance, performances of operas, symphonies, or piano sonatas very often don’t bowl over people who aren’t very familiar with the art form.

This is true of practically all art forms. I’m not very stunned by Paradise Lost, but a lot of people consider it one of the glories of English literature; I’m probably not qualified to judge. This is clearly a big problem with a lot of classical music. There are some pieces that immediately hit the spot with many people. For example, the Ride of the Valkyries is used in films and many other places, but it takes some real preparation for most people to sit through all of the Ring, and there are long stretches of it, when Wagner is filling in the back story, that pretty much bore even me, who have been enjoying it for years.

I would agree with the argument that “corporate marketing always pumps up the glitz.” I don’t know anything about best marketing practices, but I would guess that it’s far more difficult to sell the general public on opera and symphonic music through posters, etc., than it is to sell the more popular arts. I don’t have any idea how to greatly increase the classical music audience, though I think that the fact that nearly everything is now available on YouTube makes it a lot easier than when I was a kid, when getting familiar with classical music required listening to huge albums of 78s.

Jon, I think what’s compelling about my friend’s comment is that he made a distinction between moments when the action on stage rose to the level of the music, and when it didn’t (which he thought was most of the time). That would suggest he could see what was going on, even if the art form was new to him. In any case, opera isn’t all that unfamiliar. People have seen drama, they’ve heard music. And I haven’t noticed that people have trouble responding to opera when it’s superb. Remembering now a colleague on the staff of Entertainment Weekly, who watched the first Three Tenors video and couldn’t understand why people would like it much. I played her Franco Corelli, and she was completely convinced.

I think the problem in selling classical music is that people don’t care about it to begin with. So marketing doesn’t have much to build on. The same goes for popular culture. There seems to be a belief that big record companies, for instance, can sell just about anything they want, that they create markets for what they release. In the years when I worked in pop music, I didn’t see anything like that. I saw the big record labels rushing to catch up with popular taste, and mostly being successful selling things people already cared about.

Which also can be true in classical music. I heard once from a classical music marketer in a big US city that coverage — a big feature article — in the local paper wasn’t guaranteed to sell tickets. If something was going to draw a big audience on its own, an advance feature would make that audience a little bigger. But if there wasn’t much advance interest from an audience, advance publicity wouldn’t bring people in. I’m sure there are exceptions, but that seemed to be the general rule.

Yes, the American people don’t much care for classical music, these days. I suspect that if someone doesn’t start relating to it as a very young kid, as I did, it’s very hard to care about it. Now and then, someone starts to relate to in later in life, but not many do. There are so many things to spend one’s spare time on now.

As a short-term try at fixing this, there are all kinds of classical performances designed for younger audiences. I’ve seen them draw large crowds. Here in DC, the National Symphony will play several times this season in a large club. They filled a club a few years ago that held 2000 people.

The problem then is to get these people to come back. Why would they want to spend big money to come to much more formal performances in the inconveniently located Kennedy Center?

In the longer run, I think classical music has to reinvent itself as a contemporary art, and also as a contemporary kind of entertainment. What that means would take longer to tell than I have time for right now, but it’s something for the blog down the road.

I am having a bit of a problem distinguishing your complaint. Is it about marketing or is it about the performance or is it about what is being performed?

Do you have any box office figures for sold seats at the Met or the NYPhil? I cannot find them but I am not connected. What were the figures for last year?

I was writing about marketing, as I’ve often done on this blog before. In the background were thoughts about what these institutions do artistically. I’m sorry if you had trouble sorting it out. These discussions have gone on for a long time on this blog and elsewhere, so (maybe my bad) it doesn’t occur to me to set it all out clearly for those who (maybe like you) are newer to the ideas.

As for ticket sales, it’s generally known that these have declined over a long period. Getting specific data can be tricky. Orchestras, for instance, report their ticket sales figures to the League of American Orchestras, which keeps the numbers secret. There’s been a fear in the past (which I’ve had expressed to me very plainly by high-ranking people in the orchestra field) that if the public saw how bad things are, it might hurt donations to orchestras.

Some years ago I saw some of these secret figures, and things didn’t look good at all. Orchestras may be able to report an improvement in recent years, but that has to be looked at carefully. There’s been a great expansion in the number of concerts orchestras do apart from their main subscription series. So while the ticket sales to serious classical concerts may decline, it’s offset for the institution as a whole by sales to family concerts, performances of the Star Wars score while showing the movies, and many other performances designed to appeal to a large audience. There’s almost no way to sort the numbers out, because orchestras don’t disclose them.

As for opera, Opera America gave me some numbers a few years ago, showing a years-long decline in ticket sales for the largest opera companies. They once told my wife (chief classical music critic for the Washington Post) that the Santa Fe Opera was the most successful company in the US because their ticket sales decline was the smallest. Peter Gelb, who runs the Met, has been remarkably frank about their decline in sales. He was recently quoted in the NY Times as saying that classical music was having trouble maintaining its position in our culture. He called this “an uphill struggle.” https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/23/arts/music/metropolitan-opera-bam-public-theater-women.html?rref=collection%2Fbyline%2Fmichael-cooper&action=click&contentCollection=undefined®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=collection&login=smartlock&auth=login-smartlock

Another recent Times piece reported that last year the Met took in only 67% of its potential box office revenue, which was close to an all-time low. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/14/arts/music/met-opera-contract-sunday.html

Greg,

I think these reported facts are perfectly believable, which seems to me to imply that classical music organizations are financially crucially dependent on big donors, whether governments, corporations, foundations, individuals, or our space sisters and brothers, or whoever.

This has always been true since the Church and nobility paid for the music in the Middle Ages. I don’t see how it will ever be different.

The problem is that most of the donors are as old as the audience, and may not be replaced. A complaint from David Gockley, some years ago when he was general director of the San Francisco Opera: Half the money he raised came from just nine people (or some number like that), all of whom were over 70.

But there’s a lot of classical music history that isn’t well known. The big classical music institutions in the US used to get a much higher percentage of their income from ticket sales — up to 80 or 90 percent, for the biggest orchestras in 1940, according to a book published then.

And a lot of classical music activity in the past was entrepreneurial. Beethoven and Berlioz, for instance, produced concerts of their works hoping to make a profit. Other composers did, too. Handel’s opera companies in London were profit-making ventures. (Or that was the intention.) Italian opera in the 19th century was thoroughly commercial. Impresarios would rent a theater, hire singers, commission a composer, and hope for the best. The impresario in Naples had perhaps a unique solution. He opened a casino in the opera house, and ran the opera with the profits that it made. Rossini became what we’d call composer in residence at that opera house, and was so impressed with the operation that he invested in the casino.

I’m not saying we can recreate those long-gone days. But we should free ourselves from what I’m afraid is a myth, that somehow it’s built into the DNA of classical music to be supported by donors.

Greg,

Thanks for reminding me of some history that had slipped my mind. Handel, Beethoven, and Berlioz did pay their own way, in a sense, especially in their later careers. I think the idea of opening a casino may be something that ought to be looked at again, too. Hey, proceeds from the state lottery is paying for us seniors getting free mass transit in Philly. As long as people want to throw their money away on games of chance, let’s profit from it (although they should be entertaining themselves by listening to and paying for upper-class music, of course).

Even if old individual donors die off, they might be replaced by younger ones. It used to be feared by some people that the old classical musicians would die off and not be replaced, but that doesn’t seem to be happening. What I worry about is the corporate donors. Nowadays, they seem to want their names plastered on everything. The Philly Orch. plays in Verizon Hall. What if Google demanded that they change their name to the Google Orchestra for a big stipend? Ugh!

Donors often come from the audience, and more broadly from the community around the classical music institution. So if the audience ages and shrinks, and the community isn’t interested in classical music, then the donor pool shrinks. Interesting straw in the wind about that, which I read about maybe 10 years ago. In NYC, the richest zip code, and the one with the people with the most clout, used to be 10021, the upper east side. Then there was a change. Richest zipcode with the most powerful people became 10012, in Tribeca. One big difference was that the 10021 people sat on arts boards. The 10012 people didn’t. I was able to find out that vanishingly few of them went to Lincoln Center performances. So there’s a large cultural shift suggesting that in the future there might not be as many donors. Not a happy prospect.

I wish you had found an example of opera performance you find dramatic among the 100,000 options on YouTube. I don’t have $90 to drop on a cd reviewed as “hammy” by its only reviewer. I will say, I’m unconvinced that acting has gotten any worse, particularly if you get out of the enormous “barns” where facial expression goes to die. I think the problems with opera are the same as they have always been: what to do when the other guy is singing, how to make sense of singing the same words over and over again, etc. There’s something essentially unnaturalistic and stylized about opera that requires directors and singing actors of genuine genius to overcome.

Very good objection you’re making. I’ll see if I can find something. Though in fact you can find excerpts from this very performance on YouTube.

I’d guess the reviewer found this performance hammy, as you say, because the acting isn’t realistic acting of the kind we’re used to today. You could compare it to a movie from many decades ago, rather to what we’d see in a movie now. Opera singers now are better at realistic acting, on the whole, than they used to be. But they don’t, at least in my judgment, perform the older operas with as much passion as singers in previous generations had. That’s of course a judgment call, and (like all generalizations) it’s not 100% true. As the Hvorostovsky performance in the Pearl Fishers duet shows.In general, though, classical music performance used to be freer and more individual than it is now, in both instrumental and vocal music, as can be verified in old videos and recordings. My Juilliard students encounter this each year in the course I give on the future of classical music, and I’ve never had anyone disagree about this, once they hear the recordings and see the videos.

I’ll come back to the blog or this comments page with some links to videos you can see without paying anything. Thanks for raising that point! It helps me, and I’ll be able to help others when I post these links. Can’t get to it today, but I can do it later in the week. Thanks again!

I absolutely agree that performances used to be “freer and more individual.” One can hardly dispute it. The reasons for this certainly include the normalizing effect of recordings, the professionalization of the field, and the ossification of the art form (its conversion into a museum). These are all things that are hard to reverse.

As for the “hammy” acting, you are probably right, and though I’ve not seen it, I would guess that if it was not realistic acting then the performers were probably “performing” passion. And to someone attuned to that kind of acting, performed passion feels more passionate than the subtler effects of realism. But I think today’s viewers, trained by television. don’t find such performances passionate, but hammy. And wishing it weren’t so, I’m sure you agree, is not a practical response. Audiences today expect realism, and realism in opera production is, as I mentioned in my earlier comment, a terrific challenge, because the art form is designed for old-fashioned, “hammy” acting that no longer convinces.

I’d add a couple of items to your list of causes. Causes, that is, of relatively impersonal classical performance. First, the rise of analysis (of classical pieces) after World War II. Serious classical music people now believe that the heart of a classical piece may lie in analytical details. That’s going to encourage impersonal performance.

And then there’s the idea that a performer is there to realize the composer’s intentions. That puts performance in a subordinate position, and certainly doesn’t encourage musicians to explore their own intentions in a piece. Got to stick with the composer’s!

But as for people now finding older classical performances hammy, I’m not so sure. Can’t believe, for instance, that a modern audience wouldn’t fall at the feet of Artur Rubinstein. I’m old enough to have heard him in recital, and I’d swear the temperature of the room went up 10 degrees when he came onstage. He radiated warmth, excitement, personality. Both as a person and a pianist.

And I don’t see that people today are looking for realism in drama. I’m thinking, for instance, of the Black Panther, a huge hit film which apart from its pathbreaking African emphasis is a dizzyily fun superhero movie, totally over the top in the most delightful ways. Or Beyoncé’s Lemonade video, again full of wild images, many not realistic. Or think of the behavior of bands onstage. Think of music videos. I think what people expect is for things they see to be technically well-made, and there opera is likely to fall down, simply because it isn’t done well enough, whatever style it’s in.

Another straw in this wind. I was at Lang Lang’s New York debut (he played the Grieg concerto with the Baltimore Symphony). Of course he’s not a “realistic” pianist. Plays his own way, moves a lot, in some eyes makes a spectacle of himself. But the Carnegie Hall audience shot to its feet when he finished. As if there were springs in their seats! I’ve never seen such a spontaneous standing ovation.

And more recently, when I’ve seen him play in DC, he has his own audience. Not the classical audience. Younger, for one thing. So I think individuality brings people in. And authenticity. And excitement! If opera productions were more fanciful, I think they’d start to be like many of the movies people like.

Great to think about these things!

I’d add a couple of items to your list of causes. First, the emphasis on technical analysis, the idea that the heart of a classical work might lie in analytical details. That won’t encourage individuality in performance. Since, after all, the objective now is to communicate factual date.

And second, the idea that a performer’s job is to realize the composer’s intentions. That puts musicians in a subordinate position, where their intentions regarding a piece rank way behind the composer’s. So again, they’re going to step carefully.

As for audiences today and realism…I see lots of nonrealistic stuff — and wildly expressive stuff — in things people like. The Black Panther, for instance. Apart from the pathbreaking African emphasis, the film is a giddy, crazy fun superhero movie. Way over the top, and I’m sure intentionally so. The villain is about as hammy as anyone could be, and that’s part of the joy. Or Beyoncé’s Lemonade video. Full of powerful, not realistic images. Plus people watch old movies, and love them.

I was at Lang Lang’s NY debut, playing the Grieg concerto with the Baltimore Symphony. He’s not a “realistic” pianist. Plays very much his own way, moves around, some people think he makes a spectacle of himself. Well, the Carnegie Hall audience shot to its feet the moment he finished, as if they had springs in their seats. I’ve never seen such a spontaneous standing ovation. When I’ve seen him more recently play recitals in DC, he draws an audience all his own. Not the standard classical crowd. People whom I’d guess aren’t at many other classical concerts. I suspect that if we really studied this we’d find a big potential audience for things that aren’t restrained or realistic. Worth studying! I think the place to start is what people like now. Is Star Wars, for instance, realistic? The pitfall I think for classical music, and especially opera, is that people now expect things to be notable visually, and above all that the visual aspects be strikingly and professionally done. By the standards of film and TV. Won’t find that in very much opera, I fear.

“Drama in Every Breath” – love the slogan, hate the font. But I guess it has to look OK on a phone as the highest priority.

In my case, what you might call a cooler approach to opera was what I needed to get into the art form. Coming in to teenage musical awareness in the mid-70s, I hated those big vibrato scary (almost)-out-of-control voices. Nothing seemed more phony (well, country music sounded quite fake to me too, especially growing up in Texas). To fall in love with the voice and eventually opera, I had to approach vocal music through things like the Joshua Rifkin Bach B minor Mass. As has been pointed out, historically informed practice is really just a modernist performance style, so I guess I was a just an anti-Romantic. But to the larger point, perhaps each generation needs its own style of performance, which may or may not be to the taste of other generations. I have since broadened my taste in performance style, and listen most eagerly to the oldest Met performances on Sirius XM radio, but I certainly would not enjoy them if they were my first experience of opera.

Good thoughts. It’s hard to generalize, I think, about what attracts people to something unfamiliar. Or at least it’s hard to generalize without extensive research. Since the heart of the opera repertoire is 19th century opera, it’s not surprising that opera companies emphasize romance and passion. As a scrap of evidence that people outside opera think that way, think of the scene in Moonstruck where the lovers go to La boheme and are swept away.

I wonder what research the Met has on what their prospective audience thinks, or is looking for. As I said in response to another comment, I’m not sure they have much research. Or that they’ll do any in the future to see if this campaign works.

I’m sure the Met did extensive research into the motivations of opera audiences before developing this strategic content. It would be irresponsible for an institution of this size and at this professional level (and in this much trouble) to create content that wasn’t designed in direct response to market intelligence.

We weren’t privy to the focus group research, of course, but clearly the respondents said they had a powerful desire for drama in every breath and for performers who look like characters in Mexican telenovelas. Who are we to question the Met when they must certainly have zeroed in on exactly what their most promising potential audiences told them they were looking for in leisure entertainment?

I wouldn’t be certain they did research in advance. I’ve known big classical music institutions to run campaigns without research. And, which is a crucial problem, not doing research afterwards to see whether the campaign was successful. Research costs money. These institutions, no matter how large their budgets, are strapped for cash. So they may not, often don’t, do what big commercial corporations do.

I remember one story from a number of years ago. The marketing VP of a major classical music institution did some thorough research on the prospective audience, on people who weren’t coming to performances, but might. This VP told me that the board members of this institution were astonished when they saw the research. These board members included CEOs of major corporations. The VP, a good friend of mine at the time, said she sensed that the board members didn’t even expect an arts institution to do research of this kind. Of course their corporations did it, but they just didn’t expect it in the arts. Even though as board members they could have urged it!

On another occasion, I was working with a major orchestra, one of the biggest in the US. They had a campaign to interest a new young audience in their performances, and had identified “access points,” or in other words performances they thought a younger audience would be attracted to. One of these was a concert performance of Hansel and Gretel. I was surprised to hear that, and suggested to the people running the campaign that maybe millennials wouldn’t be interested in that performance. Let’s put aside the question of whether or not I was right. My point is that they were astonished to hear me say that, hadn’t thought about the question at all. Hadn’t done any research at all, had only followed their own inclinations, which I fear weren’t very well developed.

I could multiply these stories. The arts presenter whose CEO and marketing director I had lunch with not so long ago. So many questions came up, including whether it made sense to have a page of their season announcement booklet in which there was a tiny photo of the CEO surrounded by oceans of poorly formatted text. I suggested that people wouldn’t be drawn to read it. She thought they would be. The closest thing she could cite for research to back up her feeling was to say, “But some people told me they read it.”

Meanwhile the marketing director was excited about being able to send targeted messages on Facebook. If they had a cellist playing, he could send something to Facebook members who’d shown an interest in the cello. But no research to show whether this would be effective, either before sending the messages or after.

I don’t know what happens at the Met, but I’m not optimistic, based on what I’ve seen over the years. I hope I’m wrong, and that their present campaign succeeds.

Market research, ah yes! Major corporations, and even rather small ones, do it all the time, and put great faith in the practice, so much so that these CEOs were astonished that classical music folks did it on one occasion.

I’m a bit skeptical about “market research” for classical music. First of all, the term “market” implies supply and demand, sales to customers, etc. I guess that’s what opera companies, orchestras, and even individual musicians have to do to pay the rent and keep eating, but is market research as corporations do it the best approach for classical music organizations? Are there other ways to do it, besides random experiences of people working in those organizations, such as the ones you cite?

One thing that would be very useful, I think–and I suppose it’s being done–would be for many classical music organizations to try all sorts of ways of drawing in new audiences (and retaining present ones), and then have people rigorously examine which ones get the best results. This is the way scientists do experiments, e.g., how medical researchers find out which therapies work. Maybe that is the way major corporations do it too, but considering the Classic Coke/New Coke story and the like, I’m not sure they know what they’re doing all the time, either.

Of course the Met didn’t do research for these campaigns. It’s why they’re so painfully trite. This poster could have been designed fifty years ago. Nothing about it speaks to tomorrow’s audience.

If the Met isn’t researching what motivates new audiences to buy tickets, and then designing content based on their desires and expectations, Peter Gelb has no right to complain about poor ticket sales.

“This poster could have been designed fifty years ago.” — my interpretation is that the photo is deliberately retro, but perhaps it should be in b&w if so! ‘Nostalgia is not what it used to be.’

When my wife Anne Midgette reviewed the Met’s opening night, she thought the new Samson et Dalila production was deliberately retro. Imagining the piece as a past-generation Hollywood spectacular. I wish I saw some intention like that in this photo. I could imagine a deliberately retro poster looking very cool. Suggesting that some artistic ideas were brewing at the Met. Curious that the Met’s video teaser for the production shows the singers in rehearsal clothes, as if to emphasize unfancy realism. Which is not what the production offers.

I’m head of marketing for a regional choral organization.

“Market research” these days can include outgoing surveys, focus groups, etc., but can also include a lot of info that is just sitting there waiting to be examined, such as the data that can be gleaned about attendees’ demographics and ticket-buying behavior from online ticket sale platforms. Increasingly we have the ability to identify when and how people are buying tickets, and more importantly, where the clicks come from (social media? website? email campaign?). Most of these tools are free or low-cost, and their developers design them to integrate with each other, and any arts org that is not doing using these tools and taking the trouble to do this kind of gleaning and analysis is wasting an opportunity to learn about how to connect with a changing world.

BTW, nicer fonts ARE perfectly legible on mobile. More than half of marketing emails are opened on mobile devices. I agree that ugly fonts are … ugly!

From what I’ve seen, the kind of market research you’re talking about is done a lot at big classical music institutions. I’ve known a couple of experts. People who can massage audience data, and find ways to get more people to come.

But that’s all about the people who are already coming. Getting them to come more. When you want to reach to a new audience, people who don’t currently come to your performances, that’s a very different ballgame. There you’d have to think long and hard about what data you’d need, and where you could get it.