Black History Month is over. But classical music stills needs to be more diverse, every month of the year.

So another post on that subject, recycling one I wrote in 2013.

That year I led a workshop at the national conference of the League of American Orchestras. My job was to ask participants — mostly orchestra staff and board members — to imagine a glorious future. Just suppose, 10 years from now, all the problems orchestras now have will be solved! Orchestras — yours included — will have vibrant young audiences, eager support from their communities, no funding problems, and freedom to play any music they like.

That year I led a workshop at the national conference of the League of American Orchestras. My job was to ask participants — mostly orchestra staff and board members — to imagine a glorious future. Just suppose, 10 years from now, all the problems orchestras now have will be solved! Orchestras — yours included — will have vibrant young audiences, eager support from their communities, no funding problems, and freedom to play any music they like.

Yes, that’s a dream. But dreams can be freeing. Especially when, as we did in this workshop, we imagine — in generous detail — how we’d reach the dream, how we’d get from here to there.

This is so worthwhile, I think, that soon I’ll recycle my full discussion of the workshop. Of how, in this exercise of our imagination, we all freed ourselves.

But I’m mentioning it now, because during the session I threw out a challenge. We’re heading toward our bright, bright future, and now…

…it’s Black History Month!

What does an orchestra do?

Imagine that the mayor of your city — a dynamic young Latina — is leading celebrations this year of all the leading ethnic groups in your town. She’s asked all the city’s arts and community groups to take part. So again: for Black History Month, what does your orchestra do?

A nonstarter

I asked the workshop participants — there were around 80 of them — for ideas. The first I heard was one I’d expected: Play music by black composers. But, as I told everyone, there are problems with that idea. Is this music you honestly like? Is it music you play when it isn’t Black History Month? Will you play it again?

And an important point here. Black History Month is an opportunity to highlight these questions, to think harder than we usually do about diversity. But really we should address these things all year round. And, if we really want to reach the black community, do things involving them every month, not just in February.

If your answers to the questions I asked are “no,” then you’re not addressing the problem in an honest or workable way. And, as I found, years ago, talking to African-Americans involved with classical music, the black community will see right through yo. sees what you do, and thinks that you’ve failed. You draw them in, with (true examples) an opera about Malcolm X, or a piece by a jazz composer, using a gospel choir. And then you never go back to them. They don’t like that. And who could blame them?

The African-American community might also say that it doesn’t know the composers you’ve chosen, and that their music might not reflect community concerns.

Better ideas

To move further along, I imagined what other arts groups in town might be doing. For the theater company, Black History Week can be a slam dunk. They can stage one of the plays from August Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle, which, in 10 installments, looks at life in the Pittsburgh black community in each decade of the 20th century. Or, to celebrate this very special Black History Month, the one the mayor cares so much about, they can announce a 10-year project to do the whole cycle.

The dance company could commission a new dance, celebrating black life both in the past and now. Using, in alternate sections, blues recordings from the past, and current hiphop hits.

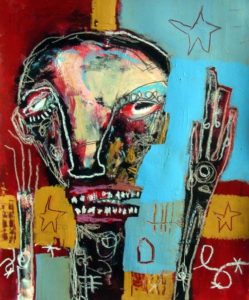

The art museum could do a show of outsider art from your town’s black community. A few years ago, at Baltimore’s stunning American Visionary Art Museum, I saw a show full of outsider art, much of it by African-Americans, and it changed my view of what art is. “Outsider art” seemed a silly term. Why label this stuff, in a way that sets it off from art by “real” artists? It’s just as strong, just as transforming as work by those with, so to speak, official arts status.

The art museum could do a show of outsider art from your town’s black community. A few years ago, at Baltimore’s stunning American Visionary Art Museum, I saw a show full of outsider art, much of it by African-Americans, and it changed my view of what art is. “Outsider art” seemed a silly term. Why label this stuff, in a way that sets it off from art by “real” artists? It’s just as strong, just as transforming as work by those with, so to speak, official arts status.

The art museum in your town, doing what I’m imagining, may knock you flat on your back, with the power of what they show. And also reveal an up to now unwritten chapter in the history of your town’s black community.

History we didn’t know

The historical society, finally, might do a show about a pioneering doowop record label, which flourished in your town back in the ’50s, even if it never had a national hit. This label (I imagined) was black-owned, which in those early days — before Motown Records, before the Civil Rights movement, before the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision had any wide impact beyond schools — would have been rare.

The lead singer of this label’s most successful group, I imagined, has run a barbershop for the last 40 years. He’s widely known in his community, and he’ll be featured in a panel discussion of what this record label did.

Back to us

So given all that, what does your orchestra do? How do you stand side by side with these other efforts?

I offered three ideas.

Years ago, I talked to an African-American cellist in the Cincinnati Symphony. In the late ’60s, he told me, Aretha Franklin (then in her first flush of stardom) did a show in a big New Jersey club. She asked for a string section, and said its members had to be black. At that point, nobody knew of many black string players, including black string players themselves. But Aretha (as I’ve seen first-hand) is a commanding woman. We don’t call her the Queen of Soul for nothing. So black string players were found. And, for the first time, realized how many of them there were.

That’s a historical moment most people — whatever their skin color — might not know about. Is there someone in your orchestra with another revealing story?

Second: the Brooklyn Philharmonic, in 2012, conferred with community leaders in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, one of the leading African-American communities in New York. They wanted to find programs that made sense both to the orchestra and to the community.

They ended up with hiphop star Mos Def, who comes from Bed-Stuy, doing some of his hits, with the orchestra playing arrangements of their instrumental tracks, made by Derek Bermel, a terrific composer who’s had commissions from big orchestras, and who’s also (as I know from talking with him) a mad hiphop fan.

So when Mos Def did his songs with the orchestra, the result was both real orchestral music and real hiphop. Mos Def (who’s now known as Yasiin Bey) also did — powerfully! — Frederic Rzewski’s Coming Together, a piece about an event in black history, which requires a speaking voice.

That’s one more model for how your orchestra might engage African-Americans, not just with something theoretical, but with something that really connects.

A third way

Finally, I mentioned a warm, revealing book by Elaine Mack, Black Classical Musicians in Philadelphia: Oral Histories Covering Four Generations. The book shows us (in such full, deep, human detail) an active classical music life inside the African-American community, much of it in generations past. Much of this, it’s safe to say, has been forgotten (except, of course, by those involved).

So one last thing your orchestra might do, to deeply observe Black History Month, would be to find people in your own black community who took part in this African-American classical music life, and celebrate them, with exhibits, and, best of all, discussions in which they can talk about their history.

Your partner in this could be the local historical society. They and your orchestra might even publish a book like Elaine’s, about your own city.

And in this way you might be going further than anyone else, because you’d be uncovering something that even the historical society might not previously have known about.

Why all this?

Here are my last words for now about Black History Month and diversity. If you expect your community — in 10 years, or right now — to take a great interest in you, you, in turn, will have to take a great interest in your community. I’ve italicized that because it’s important. Read it again! Think about it. Community relationships go both ways, something I fear that we in classical music sometimes forget.

And when you truly get involved in the community around you, it may lead you to places — including an explosive new freedom in the music you make — that you never knew you could go.

Forget about diversity–it is the perversity you learn at the university. Fight for excellence. That will draw the people who want it in their lives.