[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”o70SCvjPg0M7pqCGxfbql5xcDGwHDu54″]

I’m glad my joy posts seem to resonate with many people. This is the last of them. (See the end for links to the others.)

I’m doing this last one because in the one before, I went out on a limb, and said I loved a Rolling Stones song more than any Brahms symphony. Gasp! Making the point that — as a mark of the value we put on any music — shouldn’t be censored in any way.

But now I want to correct any thought that entertainment makes me happier than art. Which isn’t a distinction I’d make, between art and entertainment, but others make it, and I guess I’m speaking to them. I’m completely into art. It’s just that I’m an equal opportunity enjoyer.

But in the realm of literary joy, my favorite writer is Proust, who transports me. Nothing complicated about my reaction to him. I’ve never seen such precision used to map so many shades of feeling and insight. All the time describing what might be called emotional swoons. Which appear to be his own, but still he maps them precisely, the mark of an artist who doesn’t lose his footing in his art.

And my favorite movie, the one that brought me to what felt like transcendence in 1960, when it was new and I was in high school, is Antonioni’s L’avventura. A film that’s famously slow, whose narrative leaves unconcealed loose ends, and which comes to no tangible conclusion (though the wordless core of its ending, conveyed in images, a bench at dawn, a woman’s hand hesitating at first, and then touching a man’s hair, left me, and still leaves me, in tears).

Ridiculed in the New York Times when it was first reviewed. Booed at Cannes. And then, after a second screening, awarded a special prize. I thought, without being able to speak my thought, that it told my story. Just now, checking to be sure I remembered the Cannes events properly, I read in its Wikipedia entry that, in one view, it’s about “the malady of the emotional life in contemporary times,” and I think I caught on to that, finding myself in wealthy, lost Italians in all external ways different from me.

Ridiculed in the New York Times when it was first reviewed. Booed at Cannes. And then, after a second screening, awarded a special prize. I thought, without being able to speak my thought, that it told my story. Just now, checking to be sure I remembered the Cannes events properly, I read in its Wikipedia entry that, in one view, it’s about “the malady of the emotional life in contemporary times,” and I think I caught on to that, finding myself in wealthy, lost Italians in all external ways different from me.

Another kind of craziness

And then there’s my love of Webern, who can also send me into transports of joy. The way notes recur in the same register — every F sharp, for instance, being the one just above middle C — in portions of the first movement of the Op. 21 Symphony, for instance. Climaxing, maybe, in the dance of two clarinets on E and G in the octave above, like imagined, fleeting birdsong.

(It’s a mistake, by the way, to think that Webern’s music is abstract. More than half his pieces are vocal works, for a start, which means they’re explicitly about what’s in their texts. In his first sketch for an instrumental piece, Webern listed places on a walk up a mountain that passages in the music would evoke. And when he coached a pianist in his Piano Variations, Op. 27, he sang and danced to show how the music should go, and asked for dynamic and tempo constrasts beyond what he’d written in the score. An earthier composer, I’d say, than his reputation would indicate.)

And there’s the end of the last of the Five Sacred Songs for Soprano and Five Instruments, Op. 15, which is a double canon in contrary motion. As the music comes to a close, as it runs out of notes, as it comes to the finish of what it’s allowed to do, structured the way it is, I had an image of Webern suspended in the air, accepting what the canon gave him. Letting himself write notes that another way of composing might not have suggested to him, submitting himself to a discipline that might not have given him music he’d have wanted to write at any time before. Allowing the process of composition to lead him into new air, where he might find he loved thoughts, feelings, breezes, sounds unlike the ones he’d known before.

Like Schoenberg writing atonal music for the first time in his Second String Quartet, setting a Stefan Georg text that translates, “I breathe the air of other planets.”

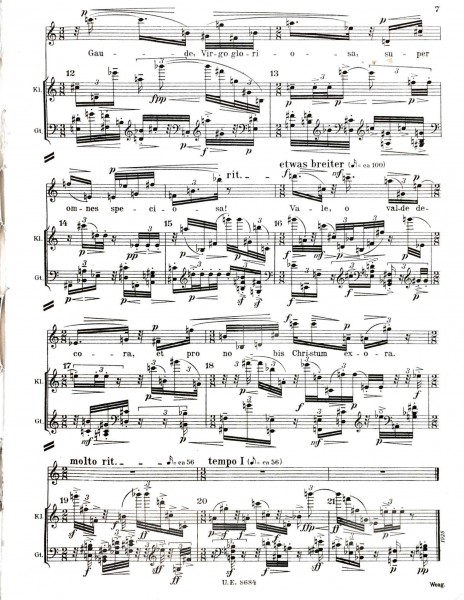

And one last thing about Webern, a crazy thing that makes me crazy with joy. How difficult his music is, and how short his pieces are. Perhaps becoming shortest and most difficult in the Three Songs for Soprano, E flat Clarinet and Guitar, Op. 18 (the instrumentation alone is pretty crazy). Which are (on the first of the two Boulez recordings of Webern’s complete works) one minute two seconds, one minute eight seconds, and one minute twenty-three second long.

And look like this (this is the last page of the last song):

Which is crazy difficult, both each part separately and all three together. To get just the rhythms right could take hours. And the soprano, ranging from high D downward as if every note in her range could be produced with equal ease, has to be superwoman.

You could say that Webern is impractical, that very few musicians (even among those good enough to handle the music at all) will devote the kind of practice and rehearsal time these pieces need, just to fill not even four minutes of a concert progrm.

But I think he’s devoted to his art. That he sees nothing but that. Which fills me full of joy.

My other joy posts:

Related to your admission that you loved a Rolling Stones song more than any Brahms Symphony, here is an insight I experienced comparing Michael Jackson and European classical composers:

“While acknowledging that such comparisons may be incommensurable for some if not most, sometimes interrelations between diverse musical forms leap out for myself transcending translucent borders, and I came to the unexpected yet undeniable conclusion that if we consider Shake Your Body, Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough, Rock With You, and Off the Wall (the song) as a single entity with four parts that one may listen to in sequence (these songs seem to naturally unify as one), the combined and greatly varied rhythmic pulsation and propulsion surpasses, in these core regards, works like Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries, Part One of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, the second movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the third movement of Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata, the Savoy recording of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie playing Cherokee, the John Coltrane Quartet playing Impressions, LA Woman by The Doors, Whole Lotta Love by Led Zeppelin, and any other rhythmically charged music I know of in the entire spectrum of Western music, possibly excepting the song Beads of Sweat recorded by Laura Nyro. A simple explanation for Michael’s accomplishment is that he managed to harness the full potency of his African and African American roots and innovations through a timely symbiosis with producer Quincy Jones.”

For those interested here is the full context: http://www.azuremilesrecords.com/thatrhythmdanceyouintosunlightthemusicofmichaeljackson.html

“An earthier composer, I’d say, than his reputation would indicate.” It seems to me that Webern, even more than Schoenberg, is a victim of his advocates in this respect: Performers giving coolly objective readings (when they don’t ignore his dynamic indications altogether) that might work for Stravinsky, but not at all for the Viennese expressionists; teachers and critics concentrating on his technical processes as though he were the Boulez of Structures I. (Maybe somebody could start a campaign stipulating that every concert of, record of, essay on, or class covering Webern’s work should be accompanied by prints of paintings by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner…)

Thank you for this wonderful appreciation!

Don’t see anything bad in loving Rolling Stones more than Brahms. Popular art is the combination that is much harder to achieve than the pure art itself.