[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”DcLxR7KIv8h3t7Xd3l54sBypZSlRABsl”]

NEW VERSION — LINKS WORK! I bungled many links in this post, for which I give so many apologies. Not helpful, to set out to show what ornamentation was like, and then block you from hearing it. Now it’s all fixed. I also bungled the link to Eva Podles in my last post. And then bungled it again, trying to fix it here. Here it is correctly. Podles is singing “Or la tromba” from Handel’s opera Rinaldo, giving a stunning display of go-for-broke virtuosity. And of how to properly ornament a da capo repeat in true — extravagant — 18th century style.

(As for why these mistakes — I didn’t quite understand how something new in my FTP software worked. But the lesson for all of us is: proofread! Check your links before you post.)

More on ornamentation — returning to the way musicians once ornamented and otherwise changed the music they performed — as a way of making old classical music sound contemporary. Continuing from my last post.

I’ll just cite examples here, notated and/or with audio, without giving much commentary.

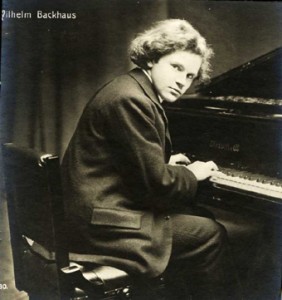

Listen to Wilhelm Backhaus, the great German pianist, improvising a prelude to a short Schumann piece, in a concert as late as 1969. Backhaus, born in 1884, was a musician of the old school. This recording comes from the last performance Backhaus gave. The announcement you hear, in German, tells the audience that Backhaus won’t be able to play Beethoven’s Op. 111 sonata, and will play Schumann instead.

It was common in past eras — the general practice — for musicians to improvise preludes and transitions in concerts that they gave. (You can read briefly about it in an excerpt from a scholarly paper I assign my Juilliard students to read. Go here, and scroll down till you find it.)

It was common in past eras — the general practice — for musicians to improvise preludes and transitions in concerts that they gave. (You can read briefly about it in an excerpt from a scholarly paper I assign my Juilliard students to read. Go here, and scroll down till you find it.)

***

In his famous 1752 book On Playing the Flute, Johann Joachim Quantz gives a short course in ornamentation, starting with the simplest of examples. What would you play if you saw, in your written music, three quarter notes, repeating the same pitch?

That’s about as simple as music can get, but in 1752, you wouldn’t have played it as written. Quantz gives 21 examples of what you might play instead:

He also shows an entire movement from a piece, written very simply, but not to be played that way. Here’s the beginning. Remember that this is just the way he would have played it. Someone else — or Quantz on another day — would play it differently.

***

Here’s a short passage from Bellini’s Norma, as it’s written in the score:

And here’s how it was sung by Giuditta Pasta, who created the title role in the opera:

I have to say I love that. So distinctive! Those quintuplets, hardly ever found in written music of the time. And that rhythmic sigh at the end — four routinely even eighth notes changed into something with more personality, a long note followed by a more flowing descent.

You can hear my notation software play these two passages: as written, and as sung.

***

That last measure, of the performed version, shows something else. It hints at how extensive ornamentation was in Italian opera, during the first part of the 19th century. Someone might do what Pasta did even in a passage that wasn’t otherwise changed. This was, in fact, the 19th century concept of rubato. Not, as we understand the word, that singer and accompaniment would together change tempo. But that the accompaniment would continue in tempo, while the singer changed the rhythm, maybe even getting ahead of the beat or behind it.

Here’s an astounding example of that, a passage from the Count and Figaro’s duet in the Barber of Seville, as sung by Manuel Garcia, the tenor who created the role of the count.

Going off the beat, almost like a jazz singer…and then that sunburst of 16th notes, replacing Rossini’s even triplets. I’m sorry that I haven’t yet worked out a rendering of this that sounds decent. (It’s not a trivial problem, as I found out, trying to get my software to play this so that the jazz-like phrasing came across.) Rossini’s original sounds, really, quite routine, next to what Garcia does with it.

And — can’t say this enough — another singer would have done something else.

(Garcia, Jr. prints this transposed a tone down, to F major. Could be that his father had a low-lying tenor voice. He also sang the title role (written for a baritone) in Don Giovanni. I thought I’d transpose it back up to Rossini’s key, so it wouldn’t look strange to those who know the music from the score.)

***

As I said, ornamentation was extensive in bel canto opera. Far more extensive than we hear today. Today, we might hear a star soprano, in a repeated section of a big aria, sing the repeat with ornaments. In the 19th century, everyone would have ornamented their repeats. (Many of these repeats aren’t even heard in current performances. They’re cut from the score, as if they were wasting time, or undignified. Whereas the point was to give the singers a chance to show how distinctive they were.)

And singers ornamented passages that weren’t repeats. They might change something the first time that it was heard. They even ornamented parts of their recitatives. If you can find a copy of The Art of Singing, by Manuel Garcia, Jr, son of the man who created the tenor role in the Barber of Seville, you’ll see all this documented.

Cadenzas might be very long, and might even change key. Garcia gives an example from one of the tenors who created many Rossini roles in Naples. He begins with something almost unknown today, a messa di voce, which means that he started a note very softly, held it, increasing in volume, until it was loud, and then diminished it to something near silence.

And not only did he do this once. He did it four times, presumably on a single breath. And then broke into a fireworks display of scales and roulades.

The purpose of all this, it’s important to say, wasn’t simply vocal display. Ornamentation could be a form of acting. That is, you change the notes of your part to give the music nuances that correspond with your conception of the character you’re playing.

Or you might change the music to accommodate your vocal range, or style of singing. The title role in Rossini’s Semiramide, to give a striking example, was written for Rossini’s wife, Isabella Colbran, who may never have had much of a high range, and who in any case wasn’t getting any younger, and maybe couldn’t sing high anymore.

So her part, as written, lies rather low. You can download a score, look at the soprano’s big aria, “Bel raggio lusinghier,” and then listen to Joan Sutherland sing the music on her first spectacular record release, a two-CD (originally two-LP) set called The Art of the Prima Donna. Sutherland, with a much higher range than Colbran (and with spectacular high notes to glory in), rewrites some of the aria so it lies more comfortably for her. Which no one in the 19th century would have blinked at. Why wouldn’t you do that? Why limit yourself, by singing notes written for someone whose voice worked much differently from yours?

***

Here’s an example of how extensive ornamentation could be, in a single aria, taken from Manuel Garcia, Jr.’s book. He gives two sets of ornaments for “Ecco ridente in cielo,” the Count’s aria at the start of the Barber of Seville. He doesn’t say whether either is what his father sang, but he much prefers the first set, saying that they fit the Count’s character better. The second set, he says, are too languid, too emotional. (I’m paraphrasing, since I don’t have the book with me.) Which again shows that the purpose of ornaments was more than vocal display.

Look at how copious, and how detailed, the many changes are. How many lovely moments come and go. And, of course, how long the cadenzas in both versions are. We just wouldn’t hear this today.

***

One problem with ornamentation, in our time, is that it clashes with the imperative — absorbed by classical musicians of the past couple of generations, like a religious edict — to perform music exactly as the composer wrote it. Because the point of playing or singing the music is to realize the composer’s intentions.

But what if the composer’s intentions were to have the music changed? That goes against the orthodoxy so many of us were taught. And so even if we make changes, we make them modestly, not quite daring to imbue every moment of the music with intentions of our own, as performers of the past wouldn’t have hesitated to do.

***

I’ll end with some musical archeology. Three recordings of “Ecco ridente,” going back in time from the modern era of classical music performance. The modern performance — modern, even if it’s from 1963 — is by Luigi Alva (from a studio recording by a cast that sang the opera at Glyndebourne, with Victoria de los Angeles as Rosina and Sesto Bruscantini as Figaro; Vittorio Gui conducted). Alva sings exactly what Rossini wrote in the score, except at the very end, when like all modern tenors he goes up the scale to a high G, instead of gracefully reclining on a lower one.

I’ll end with some musical archeology. Three recordings of “Ecco ridente,” going back in time from the modern era of classical music performance. The modern performance — modern, even if it’s from 1963 — is by Luigi Alva (from a studio recording by a cast that sang the opera at Glyndebourne, with Victoria de los Angeles as Rosina and Sesto Bruscantini as Figaro; Vittorio Gui conducted). Alva sings exactly what Rossini wrote in the score, except at the very end, when like all modern tenors he goes up the scale to a high G, instead of gracefully reclining on a lower one.

The second performance was sung live at the Met Opera in 1941, by Bruno  Landi, a tenor I otherwise haven’t heard of. A very graceful, relaxed, and winning performance (not that Alva’s any slouch), with ornaments added here and there. (This comes from a CD set I don’t think is currently available, and which had excerpts from every Met Opera broadcast in the 1940-41 season. Such a wonderful way to see what performances were like back then, and how high the performing standard was.)

Landi, a tenor I otherwise haven’t heard of. A very graceful, relaxed, and winning performance (not that Alva’s any slouch), with ornaments added here and there. (This comes from a CD set I don’t think is currently available, and which had excerpts from every Met Opera broadcast in the 1940-41 season. Such a wonderful way to see what performances were like back then, and how high the performing standard was.)

And then finally, from 1904, a recording by Fernando De Lucia, sung with a most relaxed, most personal (some might say self-indulgent) sense of tempo, with many ornaments.

Just imagine going to the opera, hearing De Lucia and other singers doing all those ornaments, each in his or her own way. Or singers of earlier generations doing even more. And then going to hear the opera again, with different singers, and now it sounds remarkably different. If you hadn’t heard a singer in one of those roles before, you might have no idea of what was coming next.

Just imagine going to the opera, hearing De Lucia and other singers doing all those ornaments, each in his or her own way. Or singers of earlier generations doing even more. And then going to hear the opera again, with different singers, and now it sounds remarkably different. If you hadn’t heard a singer in one of those roles before, you might have no idea of what was coming next.

Gives going to the opera a new and different meaning. And changes the relationship of performer and audience. I’m not saying no one does anything like this today (though maybe freewheeling invention might come more often in cadenzas in concertos than on the opera stage). But we could use a lot more of it.

Afterthought: Another striking recording, with free use of ornamentation. The Ensemble Organum singing the Kyrie from Machaut’s Notre Dame mass.

When I was studying oboe in high school I improvised my own cadenzas for the Handel Concerto I was learning. I had been reading about baroque music and so assumed this what was was done. One week my oboe teacher said “You’re playing your cadenzas different every week. I don’t mind if you write your own but you need to decide on something and stick with it.” A heated discussion ensued and he left me to my own devices.

Flash forward 20 years and I am purposefully writing music in which the performers MUST improvise or make some of their own choices in the midst of performing.

I still love classical music but I love it most when the performers enliven it in some way, not play it the way it “should” be played.

Hi, Lia. Your oboe teacher — and no blame to him; that was how people thought back then — wasn’t imagining the situation from the audience’s point of view. If your cadenzas are different every night, then no one knows what to expect. And they’re on the edge of their seats. Plus what it does for you! Gives you something to look forward to, a way to stretch yourself, in every performance. Walking in the footsteps of the great composers — stepping exactly where they stepped — is a miraculous discipline, done right. But it’s not the only way to make music. Especially when, as in this case, the great composer left the cadenza up to you.

It also strikes me that a high school teacher might tell a student to pick a cadenza and stick with it so that she wouldn’t be struck with nerves and suddenly find herself unable to think of any cadenza at all while in front of an audience or an audition committee. It would be a different matter coming from a graduate conservatory professor, whose students need to learn to do whatever they’re going to do despite stage fright.

Even so, if that’s the high school teacher’s reason, he should be able to explain it.

I’m pretty sure that wasn’t his reason. I was already an accomplished improvisor on piano and oboe and performing with a free improv group. I really did get the feeling he was just trying to rein me in because of what he thought was the “right” way to do things.

I am thankful for the fact that the whole situation caused me to have to explain my creative choices at a young age. It has served me well.

Excellent points.

Greg Sandow – the man who told us that the trumpet should “obliterate’ the recorder in Brandenburg 2 – gives advice on Baroque music.

Truly laughable.

Mr. Sandow has wandered off into the desert of supposition on what will once again fill

our concert halls if only we went back to the

days of” free wheeling ” ornamentation.

This from those free wheeling Garcia days ,,

Milan .”. latest opera Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore ” theatre full of people talking in normal voices with their backs to the stage. The singers undeterred gesticulated and

yelled their lungs out…but the noise of the audience was such that no sound penetrated except the bass drum….people were gambling, eating supper in their boxes

etc. etc …..it was useless to hear anything

..so I left ……. What is common in Italy more than anywhere else are good voices …and

the public’s instinctive love of glitter and display reaction on each other , hence the the mania for “fioriture ” which debases the

finest melodies …. and leaves the singer to embroider at will but maddens by its perfunctoriness and dreadful inevitability….”.

Berlioz

To bring in Ms. Sutherland as an example

though she pleased many as a” singer” her

yodeling had the dreadful inevitability that

Berloz speaks to ..The superiority of Podles

as a singer and master of the fioritura has

not drawn enough of an audience to her recitals to make it worthwhile her touring

the US… the yodeler in her day could

draw the large crowds as she was presented as the “real thing “to an audience

that didn’t know better and all they wanted was a high E or a shrieked out F whenever

possible.The only thing that will bring back a discerning audience is a good basic musical education beginning in public schools taught by people who know the craft beyond the musical appreciation nonsense

that now passes for some sort of music

education .

_”The only thing that will bring back a discerning audience is a good basic musical education beginning in public schools taught by people who know the craft beyond the musical appreciation nonsense that now passes for some sort of music education.”_

“Bring back” implies that there WAS a discerning audience at some point in the past – in reply to which I can also ask: When, exactly?

That said, basic musical education in public schools would certain be a good thing: even if it didn’t solve the problem of how, exactly, a composer can be original today (a problem in all past eras too, of course), it would at least intellectually and affectively enrich the general public, make classical music performances and recordings more profitable (or less unprofitable), and maybe produce a more sophisticated pop music.

But this is all wishful thinking until you have some idea about how to overcome political obstacles: from rightists who are not only against the necessarily additional spending on public schooling, but think that, if only you cut public education funding sufficiently, and government spending and taxes in general, everybody will suddenly be able to afford high quality private schooling; and from leftists who think teaching western music notation and using Bach and Mozart as examples is hegemonic.

Good lord, did that last comment ever need more proofreading than I gave it. Apologize to anyone who struggled through it.

@ Greg Sandow

You identify a real problem, but I would say it’s a problem that’s already basically been solved, and that you even intimate as much with your mention of Ewa Podleś recording of “Or la tromba.” The historically informed performance, and those standard practitioners who are influenced by it, have been working for decades – at least in theory – to make classical compositions sound of their time, including liberal application of improvised ornamention and even improvisation between written passages. At worst, the result is stupid mannerisms that are neither historical nor musically effective, but every method has its pitfalls.

The HIPers have already extended their territory from the baroque forward to the early romantics; in theory all that’s left is for them to mop up the rest of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th, and then merge with performers of more recent music. Maybe it won’t happen that way, but it seems almost ultimately inevitable, if the HIP movement itself is seen as an inevitable step in the history of performing non-contemporary classical music: from Mozart recorchestrating Handel and Mendelssohn doing the same to Bach – even though he admonished Liszt for taking too many liberties with Beethoven – to the mid 20th century standard approach of sticking roughly to the notes and parting written by the composer, but playing on modern instruments and with (then) modern performance practices – to where we are today.

Graham, the HIPsters – whom I’ve been following since the early days of Hogwood and the Harnoncourt/Leonhardt Bach cantata cycle (my infancy, of course!) – have indeed been exploring improvised ornamentation for a long time now, but in 18th-century music, they’ve tended to be a bit conservative about it, especially compared to the examples from Quantz’s treatise. (And singers tend to be more conservative than instrumentalists.) In 17th-century music they tend to be braver.

To answer “Bring back “– the 40s 50s -60s to some small degree had a more discerning

audience -they were coming from a different educational background than the

generation of to-day .Many public schools taught solfeggio as part of the teaching plan .

A great many homes still had a piano of one type or another-many people could play instruments to varying

degrees of acceptability and were acquainted with

what it took to be “good ” at the craft and

if they did go to a “music recital “could to

some degree discern a poor performance from a good one in having a more than passing acquaintance to art of music .

It would

be interesting to learn how many young people today study the piano for the sheer pleasure of playing the music ,without

a career of sorts in mind . How many

public schools teach solfege?.Mr. Clark must be aware of how difficult it is to give away a good piano -that there is a destruction site

in NY for good and not not so good unwanted pianos, grands included .With a first hand acquaintance gone the discerning audience is gone and we get the likes of Lang Lang or Bocelli who please to no end

an audience that has little knowledge of

singing or piano playing and which the clever performers dumb down to that knowledge . Remember the 3 tenors ???????

A composer is not original by forethought,

all the education in the world cannot make

one “original “nor does politics enter the

equation in a” free” society though it can cause mischief. The difference is the age ……

once in our spare time we may have played some musical instrument for our pleasure now we play video games ….

Far be if from me to deny the stupidity of today’s audience. I only question whether it was ever really better.

We had the Three Tenors and have André Rieu, but the mid-20th century had Mario Lanza and Liberace, and the nineteenth had the likes of Eduard Reményi. Maybe we played instruments in our spare time in the 19th century – though most of us would have been playing the local popular music rather than Chopin – but in the 20th we played records. On the other hand, I don’t think the number of young people who play music for pleasure is all that small even today, though many of them are playing guitar rather than piano. Then again, the guitar was good enough for Berlioz, and the piano is gaining back share of territory anyway, as rock’s popularity yields to hip hop and electronic dance music.

As for how much the rather perfunctory efforts at teaching music in public school actually stuck, I defer to Leonard Bernstein in the mid 1960s (The Infinite Variety of Music):

‘Almost nobody can read music. Or if they do, it’s a laborious torture of counting lines and spaces while mumbling “All Cows Eat Grass” or “Every Good Boy Deserves Fun” like perfect idiots. And here we have stumbled on at least one constructive step…: Teach people to read music… Any gentleman worthy of the the name in the Italian or English Renaissance could (hypothetically) read music. But what percentage of the population could that have been?… in general… it’s never been true that reading music was a common ability in any given society. But then, there has never been a society like ours, so democratically and universally educated, so open to knowledge. This is the perfect moment to begin.’

(Those last two sentences are more than a bit heartbreaking at the present moment.)

I should also note that through the time of Monteverdi, the great composers tended to be not primarily instrumentalists but singers. People certainly still sing – though admittedly, this does perhaps even less than playing piano by ear to facilitate learning to read music (and, just as important, CONTINUALLY READING music, without which people forget and may as well not have learned in the first place).