[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”qiZ0zZXyVU8dA8tN3Eh9CMuKcMrZUavs”]

From Greg:

Anyone who’s read this blog will know why the words that follow caught my eye. They’re about what a journal article I was reading called “the traditional orientation of arts presenting organizations (particularly, but not exclusively, “classical” music groups).”

This, said the paper,

might be expressed, “this is what we have to offer; won’t you come and see it?”.… To put it bluntly and in market terms: “you should want to buy this. [Now eat your peas!]” When applied to an art form that is likely to have a smaller audience to begin with – such as contemporary chamber music – this attitude guarantees what is the accepted norm for such groups: tiny audiences, shoe-string financial survival, and an existence on the periphery of the larger cultural landscape.

Which is a refreshingly blunt statement of a big problem we’ve had in classical music. This paper was published inn 2012 in Artivate, an online journal of entrepreneurship and the arts, and had been brought to my attention by Artivate‘s editor, Linda Essig, in a comment on a blog post here.

I certainly knew the author of the piece — Jeffrey Nytch, director of the Entrepreneurship Center for Music and Assistant Professor of Composition at the College of Music at the University of Colorado Boulder. I know Jeff from the entrepreneurship-at-conservatories circuit, inaugurated a lecture series that’s part of his program, and on this blog ran a marvelous guest post from him about how he promoted a symphony he’d written.

And this Artivate piece — “The Case of the Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble: An Illustration of Entrepreneurial Theory in an Artistic Setting “— just blew me away. Not just because Jeff so well stated something I myself think, but because he details one truly marvelous solution to the problem, a way to orient arts presentations toward an audience, without for a moment compromising their quality, or their artistic intent.

And he does this from his own experience. He (as, modestly, he doesn’t say in the piece) was executive director of the Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble when it transformed itself in [years TK], learning to present performances that an audience might really want to see.

With Linda’s and Jeff’s permission, I’m reprinting much of Jeff’s piece as two guest blog posts, this one, and another that you’ll see here tomorrow. I’ve abridged the piece, again with Jeff’s permission, because Artivate is an academic journal, and Jeff not only describes what happened in Pittsburgh, but places his description in the context of theories of entrepreneurship (and related subjects). So I’ve left out much of the theoretical considerations, thinking that they’re less compelling for most readers of this blog than the intensely practical discussion of what Jeff and his colleagues actually did.

Jeff did want to retain some of his theoretical thinking, and so we decided to include it as an addendum to the second post, complete with references. I’ve also retained one reference in the first post. And of course anyone who wants all the references (along with the fascinating discussion of theory they’re part of) can find them in the original paper.

I think this is some of the most important wiring my guests and I have done on this blog. It addresses a crucial question. Why should anyone go to a classical music performance? In the past, as Jeff notes, we haven’t asked that question much. Or, rather, we’ve answered it in ways that don’t work anymore. For the more than 40 years I’ve been going to new music concerts, the reason to go was that new music was important, that new works should be heard. And the reason to go to symphonic concerts, or chamber music performances, or solo recitals was that great masterworks would be played and sung, by estimable artists. Opera was conceived in a somewhat more engaging way, since there’s a stage performance, a show, in addition to music.

But still the reason for going to opera, in the end, has been to see great operatic masterworks. All this works as long as there’s a sustainable audience invested in these things, an audience that wants to hear the masterworks. And as long as there’s funding to support that.

But what happens when both audience and funding (in sums large enough to support the enterprise) start to fade away? That’s where we are now, and that’s when we need a new approach, one that says, “Come to our concert, because you’ll have an experience worth spending an evening on.” Whether or not the idea of supporting new music — or hearing classical masterworks — was high on your agenda.

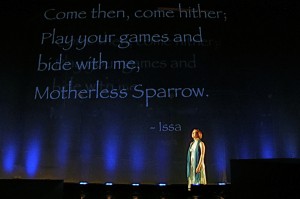

One note. Unfortunately Jeff doesn’t have photos of the PNME performance he discusses in his piece. So we’re using photos of other things they’ve done.

Here’s Jeff:

The Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble, founded in 1976, is one of the nation’s first professional ensembles exclusively devoted to the performance of contemporary chamber music. For its first twenty-five years PNME was like most other new music ensembles: founder-driven, operating on small budgets that could fluctuate widely from year to year, and with a modest audience made up of professional associates, friends of the artists, and a small core of aficionados. As the organization aged and its founder’s energy flagged, the creative energy of the participants dissipated, audiences shrank, and performance quality sagged. When the founder retired in 2001, the situation was sufficiently dire that the board of directors recognized that nothing short of a radical rebuilding of the group would save it from oblivion. After a difficult transition, new artistic and executive directors were hired with a mandate to transform the organization both artistically and, if necessary, structurally.

With the help of a major grant from a local foundation, the group undertook a year-long planning process to contemplate what needed to be done. They began by reflecting on their own significant experience as music presenters generally and of contemporary music in particular, listened to feedback from frequent attendees, and engaged in informal discussions with peer groups across the country. These conversations revealed that the challenges PNME was facing – small audiences and inconsistent quality of performances – were not unique. The result of this evaluative stage was the realization that a completely new artistic product was necessary if the organization were to break out of the pure “survival mode” in which most groups of its kind were stuck. Such a new artistic product would, in turn, likely require an organizational restructuring to execute. The directors then engaged in a creative dialogue to determine what, precisely, this new artistic product might look like.

At the core of the resulting transformation was a change of focus away from the traditional orientation of arts presenting organizations (particularly, but not exclusively, “classical” music groups), which might be expressed, “this is what we have to offer; won’t you come and see it?” This is the entrepreneurial equivalent of inventing a new widget without consideration of the marketplace and then hoping one can convince the public to buy it; when such an approach is undertaken in a commercial venue, the new widget is not likely to be a success. Yet this is the approach that the traditional fine arts have taken with their products for the better share of the last 150 years, justifying their stance by arguing that appreciating offerings of so-called “high culture” is part and parcel of membership in a civilized society. To put it bluntly and in market terms: “you should want to buy this. [Now eat your peas!]” When applied to an art form that is likely to have a smaller audience to begin with – such as contemporary chamber music – this attitude guarantees what is the accepted norm for such groups: tiny audiences, shoe-string financial survival, and an existence on the periphery of the larger cultural landscape.

A different approach

The new directors of PNME took a different approach, however. They started with their own observations regarding the experience of the audience at contemporary music concerts, pondering what characteristics a new music concert needed to have in order to be more compelling both to existing patrons and to a broader range of people. By taking a critical look at the traditional concert paradigm and informed by numerous conversations with peer organizations and audience members, they concluded that a typical classical concert (and particularly a contemporary chamber music concert, with its frequent stage changes and a programming structure that tended to string together large numbers of shorter, unrelated works) created too many points at which the audience could (and likely would) disengage from the experience. Once disengaged, it is always difficult to regain focus. The result was a concert that only the most die-hard new music fans would endure; even then patrons would often lament the breaks between works and the disconnected nature of the concert itself. This was contrasted with the experience of a film, in which most patrons will continue to watch even if they do not think the film is particularly good: the continuous, integrated nature of the medium itself makes disengagement much more difficult.

This observation regarding how audiences interact with live art inspired a new format for PNME concerts, one in which programs were intentionally restructured to create thematic unity and theatrical continuity similar to that of a film. Set changes were carefully choreographed to eliminate the disruption between pieces, and non-musical elements such as video, projected images and spoken word maintained continuity over the arc of the program (which often flowed without intermission or even pauses between works). Finally, theatrical elements such as lighting, costuming, and movement framed the program as a dramatic experience, one in which the continuous engagement of the audience was of paramount importance. The use of additional visual and theatrical elements is always with a specific intent: they must either serve the dramatic thread of the program or aid in maintaining a seamless flow (as in a video or spoken word piece that draws the audience’s focus away from a set change happening elsewhere on stage). PNME Artistic Director Kevin Noe has dubbed this model the “Theatre of Music.”

Further changes

These artistic changes in turn mandated organizational changes. In order to attract the most qualified artists capable of assuming a variety of roles beyond that of a traditional classical musician, PNME had to draw on artists from across the U.S. and internationally. Since conducting a traditional fall-spring season in this way would be prohibitively expensive, the season was converted to a summer festival format, presenting five weeks of concerts during late June and July. Given the intensity of the rehearsal schedule – and the need to schedule additional rehearsals for the many theatrical elements involved – artists were signed to contracts in which PNME was their sole commitment for the duration of the season. This in turn resulted in a different contract structure, a different rental arrangement with the venue (and indeed, a different venue), and a radically different cash flow in which the vast majority of expenditures happened during a very narrow span of the calendar, requiring that nearly all of the year’s fundraising needed to happen before the beginning of the season.

It is important to stress that the Theatre of Music has never amounted to a “dumbing down” of the artistic product for the sake of hopefully reaching new audiences, an unfortunate mistake many classical music organizations make. My observations of classical music groups across the country reveal that the first mistake made when trying to attract new audiences is to assume audience members are incapable of interacting with the music on a sophisticated level. This condescension is in fact one major reason why “dumbing down” tends to have the opposite of its intended effect. In contrast, a central tenet of the Theatre of Music paradigm is that, as stated by Elizabeth C. Hirschman and Morris B. Holbrook, audiences seeking an aesthetic experience actually welcome the “substantial mental activity” required of such experiences, and therefore demanding audience engagement with the art is not something to be shied away from but rather embraced. The trick is to create the necessary setting in which an audience can experience a meaningful mental and emotional connection to the art even when the repertoire is challenging and unfamiliar. The various elements of the Theatre of Music, coupled with extreme care and intentionality in the choosing of repertoire to create continuity and a dramatic thread, allows PNME to program challenging contemporary repertoire chosen purely on its own merits.

A single spotlight

An excellent example of how a Theatre of Music concert is structured is the Quartet for the End of Time concert, first premiered in 2009 and being revived for the 2012 season. The show opens with a single spotlight on three clay flowerpots, downstage center. The percussionist enters, sits cross-legged in front of the flowerpots, and performs Frederic Rzewski’s mystical piece, To the Earth. The staging for Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time is pre-set upstage of the percussionist in total darkness with the exception of the three candle pedestals that have been lit as the percussionist enters. During the last section of the Rzewski, the performers for the Messiaen quietly enter and take their places, so that as soon as the Rzewski concludes and the spotlight fades, the lights come up on the Messiaen set and the players begin the Quartet. To stage the conclusion of the piece – nearly an hour later – director Noe was faced with critical questions: “how does one follow such a monumental and arresting work? And how will the group transition to the rest of the program? We could just end with the Messiaen, but the reason for programming it was to place it in context and provide commentary on its impact. How do we handle that critical moment immediately following its conclusion, however?”

Recognizing that the success of the entire show hinged on this crucial point, Noe spent literally months pondering its solution. Eventually, he found the answer: John Cage’s iconic 4’ 33”, in which the time indicated is broken up into three movements of silence. What better way to follow the powerful mysticism of the Messiaen than to simply give the audience four and a half minutes of silence to contemplate what they have just heard? Furthermore, the structure of the Cage piece allowed the players of the Messiaen to exit, in sequence, and extinguish the three candles as they did. As the pianist – the designated performer for the Cage – finished the piece and extinguishes the final candle, the thunderous drum beats of George Crumb’s Idyll for the Misbegotten resound through the hall, accompanied by a blaze of lights illuminating portions of the stage that have hitherto been dark; the transition to the final piece of the program is complete. The resulting program is 70 minutes long without any breaks or applause, and creates a mystical journey of the utmost power and impact. The use of lighting is critical; no other theatrical devices were required in this case. The addition of other visual and theatrical elements are simply tools employed to transform the overall aesthetic experience of the audience; the ultimate goal is to maintain engagement so that patrons can effectively connect with the expressive impact of the music.

Framing the art

This approach to concert design is in direct contrast to artists or arts organizations that consciously choose their material based on what they believe will appeal to the broadest possible audience by asking the least of them (i.e., modifying the core artistic content to cater to the lowest common denominator in perceived audience tastes). Therefore, what distinguishes the PNME model is not a compromise of traditional artistic standards (quality of repertoire and/or performance), but rather an innovative approach to how the art is framed and integrated into a dramatic/theatrical experience. The entire concert becomes a work of art in itself – a work designed with the utmost attention to detail and polish at every level and structured with the audience’s experience of that work always foremost in mind.

In addition to being of interest to artists and presenters, the PNME case is an important entrepreneurial study as well. The premiere performance of the “new PNME” enjoyed attendance that was a company record at that time. In the eight years since the Theatre of Music was unveiled, season attendance has grown more than 600 percent, a trend driven primarily by word-of-mouth and leveraging social networks as opposed to traditional marketing methods. In addition, the company has released two commercial recordings and received numerous accolades from critics, including special recognition at the International Fringe Festival in Edinburgh, Scotland. PNME’s transformation was an extraordinary entrepreneurial success – success driven by artistic innovation designed to connect their audience with their art.

This post is excerpted from “The Case of the Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble: An Illustration of Entrepreneurship Theory in an Artistic Setting” by Jeffrey Nytch, originally published in Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, volume 1, issue 1. You can access the full text at http://artivate.org.

The content of this article is copyright by the author. All rights reserved.

Jeffrey Nytch enjoys a diverse career as composer, educator, and consultant. He holds dual degrees in geology and music from Franklin & Marshall College and masters and doctoral degrees in composition from Rice University. Previous to his tenure as Director of the Entrepreneurship Center for Music at The University of Colorado-Boulder, he was Executive Director of Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble and maintained a busy freelance career as a composer. In addition to these ongoing pursuits, Nytch has begun a consulting practice in which entrepreneurial principles are applied to strategic planning for arts organizations and other non-profits.

Jeffrey Nytch enjoys a diverse career as composer, educator, and consultant. He holds dual degrees in geology and music from Franklin & Marshall College and masters and doctoral degrees in composition from Rice University. Previous to his tenure as Director of the Entrepreneurship Center for Music at The University of Colorado-Boulder, he was Executive Director of Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble and maintained a busy freelance career as a composer. In addition to these ongoing pursuits, Nytch has begun a consulting practice in which entrepreneurial principles are applied to strategic planning for arts organizations and other non-profits.

Reference

Holbrook, M., and Hirschman, E. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research 9 (September), 132-140.

What a phenomenal post. You’re right that this article hits the nail on the head about the problem with the approach of most classical music organizations. The description of a sample contemporary music concert paints a picture of a breathtaking musical and emotional experience – which, of course, we all want our performances to be.

I’m most interested in the line between this kind of “theater of music” experience and “dumbing down.” For me as a performer, “dumbing down” doesn’t have to do with repertoire selection per se, as the article implies. Perhaps this impression comes simply from the choice of a contemporary music ensemble as subject for the analysis. For other classical music ensembles, there’s plenty of musical and artistic depth to offer in Beethoven 5; we would be foolish to eschew it specifically _because_ it is popular.

“Dumbing down” to me concerns the core musical and artistic values of the piece. Do we sacrifice technique? Do we sacrifice musicality, or preparation? That’s dumbing down. When we put a pop singer onstage to croon Nessun Dorma, we are dumbing down. When an ensemble stops striving for top caliber musicality because they can get away with it, they are dumbing down. But there are many improvements to accessibility that we can make without making such core sacrifices. Picking hummable pieces or adding bright lights and costumes is not necessarily dumbing down. Pick whatever rep you want, and turn on whatever lights you want – as long as _an extraordinary musical experience for the audience_ is the core focus, I will never accuse you of dumbing down.

Furthermore, with some (great) pieces of music, the simple fun of the piece is a core part of the musical experience. It’s OK to find Callas’ high notes in Sempre libera thrilling and exciting – that’s a big point of the piece. The fireworks in Ah non giunge are musically critical, so enjoying them on a “shallow”, visceral level is a totally valid musical experience. It is in no way musically less valid or valuable than the contemplation available in Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder; it is simply a different kind of extraordinary musical experience.

Another way to express this is that the moment the _production_, rather than the musical experience, becomes the focus, we are dumbing down. All of those “cast proof” productions of La Bohème at major respected opera houses, I’m looking at you. I’d prefer a Pavarotti singing the guts out of Nessun Dorma on a rock’n’roll stage using Sting to sell tickets, thank you very much.