[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”0r9ca5TFWpUXf04Mo0vvkAc7rPMbjw1M”]

There’s been a lot of fuss online about a piece that showed up on Slate, about the death of classical music. Well, maybe it meant to be about the decline of classical music, and certainly included a strong array of facts and figures, more than I’ve usually seen in writing on this subject, no matter what point of view the writer take.

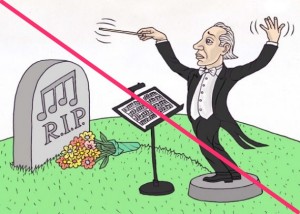

But because the headline on the piece was “Requiem: Classical Music in America Is Dead”…because of the graphic I’ve reproduced here, which led off the piece (and which I’ve crossed out, because I disagree with what it’s telling us)…and because the piece began with a quick one-liner, more clever than wise, that made a joke about classical music being dead…because of all these things, people understandably think the piece is about the death of classical music.

But because the headline on the piece was “Requiem: Classical Music in America Is Dead”…because of the graphic I’ve reproduced here, which led off the piece (and which I’ve crossed out, because I disagree with what it’s telling us)…and because the piece began with a quick one-liner, more clever than wise, that made a joke about classical music being dead…because of all these things, people understandably think the piece is about the death of classical music.

When it comes to classical music and American culture, the fat lady hasn’t just sung. Brünnhilde has packed her bags and moved to Boca Raton.

Because this has stirred up so much fuss — and because I was interviewed for the piece — I thought I’d say a few words about it. Of course I had nothing to do with the context anything I said was put in (though I do think my quotes were accurate). Or with what larger points the piece might make.

But I do think it’s both wrong and unwise to say that classical music is dead. Unwise, because the statement is imprecise. Do we mean the music itself is dead? Or the industry supporting it? Has Beethoven lost all vitality and meaning, or is it just your local orchestra?

That’s a minor quibble, though. What matters most is that the statement is — so very clearly — wrong. Classical music may be in all kinds of trouble, but it plainly isn’t dead. The music still gets performed. Many people love it. Many people learn to play it. The institutions, troubled as some of them may be, still function. Even if you think that they’re declining, even if you think some of them will be out of business in a decade, they still exist.

And then, as the piece in fact does say (though without the force of its death one-liners; I only quoted one of them), classical music is changing. New things are happening, vital new things, which can — and very likely will — transform the field. So far from being dead, classical music is reviving. And may be transformed. Reborn. Come dramatically to more invigorating life than it might be showing now.

So when we talk about the problems that the field is having — and what dark places they might take us, if things don’t change — we ought to use more measured language. That’s why I don’t talk of life or death. Instead I try to say, more carefully, that classical music, in its present form, as an enterprise in our society, might not be sustainable.

Which of course is because of that familiar one-two punch, declining audience and funding. And then we have to add, very quickly, that things are changing, and that the field may change enough to be sustainable once more, though my belief (which you’re free to disagree with) is that things will have to change a lot. And that when the changes have deeply taken root, classical music will look, much more than it does now, like the culture that surrounds it.

It’s always good to restate these things, to keep our discussions sane. I’d add that, at least for me, it doesn’t matter much that someone uses scary language. I take a longer view. It’s just a momentary outburst.

But I do understand why people get upset. Some, I think, don’t want to believe that classical music really is in any danger, because they love it so very much, and so to say it’s dead outrages them. Others (out of just as deep a love) are working hard to fix the problems, and so they, too, are upset, because they so passionately don’t want classical music to die.

Maybe some good can come from this Slate piece, if it inspires some of us to do even more to fix the problems classical music has.

Well Greg, as you know, ROCO focuses on our musicians who are alive. We are not necromancers. The relationship through our language of music with our audience and collaborators and community has never been stronger. Our musicians know the names of our audience members. A place to belong and be present.

The WQXR follow-up says the author’s EDITOR came up with the sensational title. I’d assume the picture too.

Personally, I think it’s very clear that classical music IS in fact dead for let’s say HALF of Americans. It is up to us to RESURRECT it for as many as possible. In fact, the music is just silent dots, circles and lines on a sheet of paper until musicians read it, imagine it and bring it back to compelling life. It’s an appropriate metaphor when we examine it as a raw truth rather than feeling personally offended.

Amusing, I blogged on this same subject this morning using the very same graphic – Oi vey! Not Another One! http://bit.ly/1d6q27W At The Discovery Orchestra we believe the real “crisis in classical music” is this. It is the absence of perceptive music listening as a consciously cultivated behavior in our society. Becoming better listeners in general would help so many aspects of American personal and civil life. From a personal growth standpoint, a widespread embrace of perceptive music listening would bring heightened pleasure to millions of individuals as they listen to music of all genres…classical, jazz, pop, rock – you name it.

Yo-Yo Ma recently contributed a wonderful article to the Huffington World Post – ironically on the very same day Mark Vanhoenacker posted his Requiem for classical music on Slate. Maestro Ma wrote: “Underneath the water is the life I’m leading, the thoughts I’m thinking and the emotions that well up in me. We all get into trouble if we think the universe only exists of the matter that we can see and measure, and not the anti-matter that is the counterpart that holds it all together.”

Yo-Yo Ma here underscores the very essence of abstract music. Like Yo-Yo Ma’s unseen “anti-matter,” the powerful emotional communications of abstract, wordless music are invisible. Whether a movement from a Bach Unaccompanied Cello Suite or Angels on My Mind by jazz pianist Joe Sample (click “show more” and then click 49:12 by No.10) – these wordless musical expressions give us access to “the life I’m leading, the thoughts I’m thinking and the emotions that well up in me…underneath the water.” This is why it is so vitally important for us to become perceptive listeners who notice the myriad musical details of abstract music as its invisible sound waves penetrate us – and to encourage others to do likewise. At The Discovery Orchestra, we will persist in this endeavor!

George Marriner Maull, Artistic Director

The Discovery Orchestra

Whether it’s dead or dying or whatever I don’t know. I do know that the orchestra in which I spent most of my active career (Boston) is very much alive and that they deposit a pension check in my account every month (which is more than a lot of “alive” companies do for their retirees).

But of course it is in trouble; it has always been, ever since I remember (and I began in Cleveland in 1960). However I don’t believe it is in any more trouble than all the other institutions of our failing society (not that that is much comfort) and I have some doubt that in 50 years, long after I am gone) that any of the entities which I have taken for granted all my life (like, say, reliable electric power, safe water, or fresh produce at the corner market).

Anyway, as long as we are doing an autopsy (or vivsection?) let me add my perspective.

It is remarkable at all that our art has lasted as long as it has; it’s vital period lasted around 250 years, and that is a long time for any institution at any time, especially given the rapidity of change in our time (think about it, someone who was five when the CSA surrendered in 1865 would have been 85 when the first A-bomb exploded over Hiroshima — one lifetime!) And it was a living art mainly because it was not primarily the preserve of highly trained professionals (as it is today, for which broadcasting and recording have much responsibility) but was OF NECESSITY practiced by a relatively small but relatively influential group of proficient amateurs. And since music doesn’t exist on the printed page but must be realized in sound, that was the main way in which it was both performed and heard. Before recordings, when a new symphony by Brahms or a new piano sonata by Beethoven was published, the best and sometimes only way for music lovers to get to know it was TO PLAY IT THEMSELVES. A first-class performance by well-trained professionals was like to be an event remembered for decades (much the way I remember being taken to Ebbetts Field by my father at age 10, in 1950 — no ball game seen on TV has made such an impression on me.) and that is why there is a huge repertoire of symphonies and even string quartets arranged sometimes by the composers themselves for piano four-hands; it is also why no upper middle class person was considered cultured unless they were adept at an instrument. This arrangement, once copyright laws were in place, enabled composers like Brahms and others far less skillful to make comfortable livings off of the sale of printed copies of their works. When I was a student and young professional, I played late Beethoven Quartets with older men who were doctors, mathematicians, and physicists —- all of them of European. Do such people exist now? if they are, they are mostly old and dying off. And “classical” music (how I hate that misnomer!!!) is too often just more sonic wallpaper, which presages a slow death from indifference.

What can be done?….that one is beyond me. I’m content to enjoy my retirement as a passionate amateur (root meaning = lover) and let whatever music is to come come in its own time. But for me at least, the past is not dead….it’s not even past!

Yes, it is dead. And it’s a tradgedy. It’s dead because the people in charge of it mismanaged it. Made it too elitist, made it a snobby game not only to shut out people who are unfamiliar with it but for those musicians that don’t fit in with the snobby establishment. It’s dead and I blame them. So many fine musicians come out of conservatory and university programs, but so few can find meaningful and gainful employment. It is a bitter pill to swallow. All those fine minds could be spreading the beauty of music, but it’s an old boys club perpetuated by its old boy audiences. R.I.P.

I have to agree with C. Loveworthy above. I am a “highly-trained, finely-seasoned” classical musician myself. And posting under a pseudonym. I have loved playing and even then teaching music in days less recent when student numbers were more healthy. But a good number of the classical musicians in my city tend to use any knowledge of the form as some kind of snooty competitive leverage against each other, and certainly as a means to make those who aren’t trained feel like lesser class. Everybody snicker and throw your nose up if some poor innocent pronounces Wagner or Johannes the way that it looks. After awhile, I stopped attending concerts, just because I couldn’t stand that mentality in too many of my colleagues.

C. Loveworthy states categorically “Yes, it (classical music) is dead.” Why? Because it is mismanaged, elitist, snobby, shuts out people who don’t understand it or musicians who don’t fit in. And, it’s an old boys club perpetuated by its old boy audiences. There you have it, all the stereotypical arguments against classical music. Now all we need is for this person to be identified as a female ethnic minority and the picture is complete.

I say “hogwash.” (Or words to that effect.) Yes, in some very well-known cases it is mismanaged. (See: Minnesota Orchestra) But the rest of the critique is defeatist and misinformed. To begin, a degree in any subject does not guarantee gainful employment, whether it’s business, law, medicine, art, philosophy, journalism, architecture, or music. We have too many well-trained graduates of music schools for all of the available jobs. (The same is true for athletes, actors, and journalists.) But, all that education. Training, and talent is not wasted unless they are waiting for the world to come to them. There is no one stopping them from creating their own venues, genres, and opportunities. This is happening with every new string quartet, chamber orchestra, or community music school.

Music is not a male-dominated field with male audiences. Women equal or exceed the number of men in the majority of American orchestras. Audiences have been largely older females, although that is changing. You need only look at the first comment in this article to find a female founder and director of a new chamber orchestra. Other comments offer new and creative ways to reach new audiences.

While we musicians recreate the music of master composers, most of whom are dead, we also have creative minds that invite, even demand use. I would encourage Ms. Loveworthy to use her obviously intelligent mind to break through a few glass ceilings of her own creation. My guess is she has a lot to offer.

The problem starts with those snobs who insisted on calling it ‘Serious Music.’ The implication being that other music was what? Frivolous? Serious music for serious people. So those that enjoy other forms are not serious people. Listen to the blues some time and you’ll hear some serious music.

Along with “classical” music, jazz isn’t faring very well. I think the “elephant in the room” is that purely instrumental music has little traction. It is too abstract: folks seem to need something more than just music, it needs to be sung.

Great. A tyranny of singers.

I fail to understand why it is so hard for people to sit quietly and listen.