Yes, the classical music crisis, which some don’t believe in, and others think has been going on forever.

This is the third post in a series. In the first, I asked, innocently enough, how long the classical music crisis (which is so widely talked about) has been going on. Answers poured in, here and on Facebook and Twitter. The answers — as I said in the second post — suggested that we don’t know how to talk about our crisis, because we don’t have enough information. Compared, as I’ve said before, with data that’s widely available about other industries in crisis, like newspapers.

In future posts, I’ll show why non-crisis beliefs — that we don’t really have a crisis and that the crisis has always been with us — don’t hold water. I’ve worked in classical music, as a student and professional, since the early 1960s, and I guarantee that there wasn’t widespread talk about a crisis, about classical music being endangered, until perhaps the 1990s. Though hints of it had surfaced earlier.

I’ll also offer data — from my own experience, and from what others report — that can teach us when and how our crisis showed itself.

But first, a crisis overview, a verbal diagram of what the crisis is. Starting with this: What was classical music like before the crisis?

A popular art

Yes, classical music was popular. Not as popular as popular music, not as popular as radio (going back before the age of TV) or the movies, but popular enough to be made fun of, in movies like the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera.

Classical music filled the airwaves. Dozens of orchestras, mostly American but some from abroad, had at least some of their concerts broadcast on commercial radio. Classical broadcasting was profitable. So was classical recording. In the 1930s, the leading American record company, RCA, made half its money from classical music. NBC, the parent company of RCA, created an orchestra for Arturo Toscanini to conduct — hyping him as the greatest musician who ever lived — and aired its concerts first on radio and later on TV, with commercial sponsors.

Classical music filled the airwaves. Dozens of orchestras, mostly American but some from abroad, had at least some of their concerts broadcast on commercial radio. Classical broadcasting was profitable. So was classical recording. In the 1930s, the leading American record company, RCA, made half its money from classical music. NBC, the parent company of RCA, created an orchestra for Arturo Toscanini to conduct — hyping him as the greatest musician who ever lived — and aired its concerts first on radio and later on TV, with commercial sponsors.

Orchestras survived the Great Depression virtually unhurt. The big orchestras made cutbacks, but not drastic ones. New orchestras were created. Half of all orchestras that existed in the US in 1940 were founded during the depression, despite 25% unemployment and a huge drop in industrial production. Which could hardly have happened if classical music had been in crisis.

The Metropolitan Opera, in the 1920s, made a profit from its operations.

Classical music was widely covered in the media, written about in newspapers and in the most popular magazines. Classical artists were often on the cover of Time, a magazine whose covers were for generations accepted as a measure of what mattered to Americans. (Does anyone remember one of the Landshark episodes from Saturday Night Live, when the landshark tries to get into an actor’s dressing room, by saying it can get the actor on the cover of Time?)

Renata Tebaldi was on the cover of Time when she opened the Met Opera season as Tosca in 1958. Crowds poured into the street to parade with her after the performance, and the New York Times called her “America’s sweetheart.”

Renata Tebaldi was on the cover of Time when she opened the Met Opera season as Tosca in 1958. Crowds poured into the street to parade with her after the performance, and the New York Times called her “America’s sweetheart.”

Operas ran commercially on Broadway. Not just Porgy and Bess, but also [rewritten in 2023] five productions of operas by Gian-Carlo Menotti, whose operas were also shown for a mass audience on network TV. One of Menotti’s operas ran for eight months on Broadway. These were real operas, with complex music, full operatic singing, and large symphonic orchestras. Britten’s Rape of Lucretia — which might not seem like a commercial piece at all — had a Broadway run.

[added in 2023] In 1951, the NBC network commissioned Menotti to write a Christmas opera, Amahl and the Night Visitors. When it was premiered, it was so popular that NBC showed it again each year, until well into the 1960s.

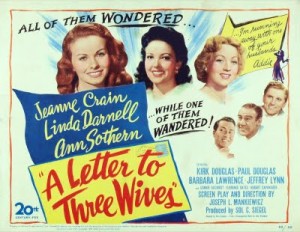

Classical music showed up in the movies. Not just in films that were about classical music and classical musicians, but in casual references, which more vividly show us how large a part of life classical music used to be.  To give just one example: in an Oscar-winning 1949 film, A Letter to Three Wives, [slightly rewritten in 2023] a character played by the big star Kirk Douglas gives a party, and entertains his guests by playing, on his spiffy new record player, a recording of the second Brahms piano concerto. All of it. Which his guests accept as perfectly normal.

To give just one example: in an Oscar-winning 1949 film, A Letter to Three Wives, [slightly rewritten in 2023] a character played by the big star Kirk Douglas gives a party, and entertains his guests by playing, on his spiffy new record player, a recording of the second Brahms piano concerto. All of it. Which his guests accept as perfectly normal.

Chamber ensembles and vocal and instrumental soloists toured throughout the US, performing even In small towns. In 1962, Life magazine, one of the most popular American magazines, commissioned a piano piece from Aaron Copland, and printed it for its readers to play at home.

[rewritten in 2023] And people of all ages were in the audience. College students went to symphony concerts on dates. Teenage fans mobbed the Met for the star soprano Geraldine Farrar’s farewell performance, and threw flowers on the stage, hung banners from the balcony, and followed her in the street after the opera was over.

[added in 2023] Studies showed how young the audience was. One, done in Minneapolis in 1955, showed that people attending a symphony concert had a median age of 35, meaning that half of them were younger. A New York Times story on the study didn’t mention the audience age, from which we can guess that the data seemed normal at the time. Another study of orchestral audiences, done in two cities late in the 1930s, showed a median age of 33 in Los Angeles, and 27 in Grand Rapids, MI, which seems strikingly young. The results of the study were reported in a 1940 book on orchestra finances, The authors of the book had no comment on the age of the audience, which, again, suggests they thought the data was no surprise, that this was what they saw when they went to orchestra concerts.

MIT students snakedanced through the streets when it was MIT night at the Boston Pops. Harvard students came to the Pops and made trouble, loudly demanding the Brahms Academic Festival Overture, which features college songs (one of which, “Gaudeamus igitur,” I myself sang in my high school glee club in the 1950s).

None of this meant that classical music institutions didn’t have problems. The Met Opera considered canceling a season in the 1970s, as its general manager at the time, Schuyler Chapin, once told me. (They didn’t do it because, when they ran the numbers, they found they’d lose more money shutting down the house than they would be keeping it open.)

[everything after this rewritten in 2023] Major American orchestras faced financial disaster late in the 1960s, and feared — as was reported in newspaper stories — that they’d go out of business. But that didn’t mean that classical music itself was in trouble.

The orchestras hired a major consulting firm to give them help in this crisis, and I’ve read the consultants’ report (which is in in the New York Philharmonic archives). One thing the report says is that the orchestras were playing to full houses — they were selling 100% of their tickets.

So clearly they had an eager audience. Their trouble was purely financial. Many orchestras now play all year, signing their musicians to 52-week concerts. But before the 1960s they didn’t do that. They played only about 40 weeks each year. During the summer, they didn’t pay their musicians, who had to take whatever other jobs they could get. Some of them worked as salesclerks in stores.

It was in the 1960s that the big orchestras expanded to 52-week seasons. But their financial planning was bad. The expansion cost more than they expected, and the income they got from additional ticket sales was lower than they’d hoped. That’s why they faced financial disaster at the end of the decade. So this was a crisis of bad financial planning, not a crisis of classical music. Other forms of classical music — opera, for instance, or chamber music — weren’t affected.

The late-’60s financial crisis used to be cited by people who didn’t believe classical music is in any special crisis now. They thought it showed that classical music is always in crisis. But that’s not right. There was nothing wrong with classical music at that time. The larger picture shows classical music as a healthy, vibrant, central part of our society all through the 1960s.

And then…

Stay tuned for the next post in this series.

Why do you spend so much time arguing with crisis deniers, Greg? You’re like Nate Silver before the election and they’re like Karl Rove. History will prove that numbers trump wishful thinking so there’s no sense in trying to appeal to people who don’t count.

Very good point, Trevor. I spend time with them because they have a surprising amount of influence inside the classical music business. If I were arguing these points simply from a scholar’s or a journalist’s point of view, I agree — it would be like working on global warming, and spending half my time with climate change deniers.

But I’m working inside the classical music field in a more practical way, and if people in a position to change things are going to deny that the crisis exists, then they have to be refuted.

Thanks for the Nate Silver reference. He’s one of my heroes. And I happened to be watching Fox News election night (just about the only time I’ve ever watched) when Karl Rove threw his incredible hissy fit, rejecting the work of Fox’s own researchers. Who came on camera to say that they had 99% confidence in their projections. (Which of course turned out to be correct.) A moment I’m not likely to forget!

It’s so important to keep this particular conversation happening for precisely the reasons you’ve outlined, dear Greg! Like it’s important to keep talking about climate change here in Australia at a time when our ruling conservative party has abolished our Climate Change Commission, the body who used to inform the parliament about the latest scientific data in regards to global warming. Sceptics have power and we need to keep fighting the proverbial good fight.

It happened due to the WPA and Federal Music project funding. Nearly all the WPA orchestra formed during the depression era no longer exist. It’s actually a similar to the economic bubble that happened during the Rockefeller/Ford funding years (and to a lesser extent the 90s boom). In both periods there was rapid expansion, and after the funding ceased the industry was forced to adapt for funding. Few enough of us would recognize popular music from that era. With the exception of niche groups like Pink Martini we have no more Sinatras, Dean Martins, Edith Piafs singing to full scale backing orchestras and the era of the big band is effectively over too. The cost disease will eventually negatively affect any kind of industry where the product (e.g. live performance) requires significant human labor. With the funding that came from the dying broadcast media and big labels drying up as those industries hemorrhage, sports and popular music will follow course too as they are already showing signs of doing.

Jon, you and I should get our facts aligned. When I said the number of American orchestras doubled during the depression, I was paraphrasing something in Grant and Hettinger’s 1940 book, America’s Symphony Orchestras and How They Are Supported. Which, as I think you know, is the main source (and in fact, as far as I know, the only thorough source) for information on American orchestras in that period. Grant and Hettinger say that, of all the orchestras in the US in 1940, half had been founded since 1929. Which meant they were founded during the depression.

Were they WPA orchestras? For the most part, they couldn’t have been. Grant and Hettinger say there were about 300 orchestras in the US in 1939. (This means professional or semiprofessional orchestras, and excludes orchestras in schools, of which there were an astounding number.) 36 of the 300 were WPA orchestras. (Or, more specifically, Federal Music Project orchestras, since it was the Federal Music Project, not the WPA, that created the orchestras.) So if half the 300 orchestras were founded since 1929, that’s 150 orchestras. Federal Music Project orchestras were only 24% of them.

Chapter two of Grant and Hettinger’s book is titled “Forces Underlying Recent Expansion,” a logical subject to explore, since the great expansion in the number of orchestras was one of the most striking facts about orchestral life at the time the book was written. This chapter doesn’t mention the Federal Music Project (or the WPA) at all. Many reasons were suggested for the increase in the number of orchestras. Music education in schools, which increased the number of musicians available. Movie theater orchestras, in the days of silent films, which got large audiences used to hearing symphonic music. And then, when sound films came in and the movie orchestras disbanded, made large numbers of musicians available for symphonic work.

Another factor was the rise in recorded music, which again helped to increase demand for live orchestral concerts. Many people heard orchestral music — in school courses, for instance — who’d never heard it before. Radio was a big factor. As I said in my post, many orchestral concerts were broadcast commercially. Again that created demand. (In a survey Grant and Hettinger quote later in the book, when people were asked what had gotten them interested in going to hear orchestras live, radio broadcasts were the most common reason given.)

And then finally economic factors — the great rise in prosperity in the ten years before 1929 created a hunger for finer things like orchestras, which persisted even during the depression.

So, Jon, if I believe this authoritative book, it would seem that WPA (or Federal Music Project) orchestras didn’t loom at all large in the big orchestral expansion of the 1930s. If you have other data from other sources, I’d love to see it.

Yes, Greg–I know that’s the source you were paraphrasing and I said as much when I responded to your posting of this blog on your facebook page. Yes, only 36 of the FMP/WPA (really just two stages of the same program when the former transitioned into the latter) constituted the 150 (or half) of the founded orchestras from 1930-1940. However, as I said in my facebook reply that number “implies the fully funded (36) WPA Orchestras as well as the joint efforts of the FMP/WPA and communities initiatives.” The Hettinger/Grant books doesn’t give the numbers of the jointly formed FMP/Communitive funded orchestras.

I also find it odd that there is no mention in chapter two of the FMP/WPA since the program was also responsible for education initiatives and recordings which they also distributed to radio stations.

apologies for not closing the ‘blockquote’ tag–hope it’s still clear what I was quoting and which words are mine.

Jon, I think we should talk about one subject at a time. You made a very broad statement about the expansion in the number of US orchestras in the 1930s — that the new orchestras were Federal Music Project orchestras, that most didn’t survive the end of the FMP, and that this was a bubble, leading to a kind of collapse.

The figures I quoted show that what you said couldn’t be true. If you now want to talk with me about the overall role of the FMP in the classical music world of that time, I can’t help you, because it’s not a subject I know much about.

Though if you wonder why you and Grant and Hettinger might have different views on the FMP’s role, I’d offer one thought. They (very thorough observers) were there, and you weren’t.

Actually, Greg, the FMP role in the expansion and growth of music, mjusic education, the recording industry, and radio during that period is a matter of public record–it was a Federally funded project after all. Which is why I found it odd that the Hettinger and Grant book don’t really mention it.

I understand there my have been a conflict of interest given that Nikolai Sokoloff (director of the FMP) was one of the National Orchestra Survey directors and that Harry L. Hewes (project supervisor of the FMP) was one of the main sources for information about the state of orchestras via the 1936-1939 interviews–especially given their not so congenial relationship (see the chapter Contradictions of Creation in the book, All of This Music Belongs to the Nation: The Wpa’s Federal Music Project and American Society).

I never said the bubble collapsed. Speculative bubbles refer to the phenomenon of artificially inflating economic environments, hence why I quoted the Russell Taylor quote as that was the Ford Foundation report was also stating.

I’m not even claiming the crisis was perpetual so much as it ebbed and flowed depending on the circumstances.

Jon, be a historian, please. A real one. Or at least think like one, while we’re having these discussions. Look at the larger picture, not just individual facts, no matter how many of them you might accumulate. You need to put those facts in a context. The classical music crisis isn’t about immediate financial problems that anyone might report, for any institution or group of institutions, at any time. And least of all is it about the orchestra financial problems of the late ’60s, which were (as everyone in the field knows, and as has been said many times) entirely due to overexpansion earlier in the decade. This has nothing at all to do with a larger classical music crisis. A larger crisis would affect the whole field, all (or almost all aspects of it). So if the ’60s orchestra problems had been an overall classical music crisis, it would have hit opera companies. Chamber music groups. Presenting organizations would (as they did in the early ’90s) start cutting back on classical concerts because the audience for them wasn’t there. None of that happened. Record companies would have cut back on their releases, and sold notably fewer copies of their records than they did in past decades.

Etc., etc., etc. I’m going to set forth the dimensions of the present crisis in a future post, and anyone will be able to see that — if they believe that what I describe has really happened — that what we’re seeing now is like nothing we ever saw before.

One detail from the McKinsey report (or rather one of them, because there were two). The Big Five orchestras, at the end of the ’60s, were selling 100% of their tickets. Or so the consultants said. Not likely, then, that there could be a crisis in classical music, as an art form with a social position in US culture of the time. A financial crisis, yes. But not a crisis of the art form in any larger sense. As someone said here in response to you (I’m chagrined at not remembering his name) the perpetual financial crises of the airline industry don’t mean that air travel hasn’t been popular. They have causes of their own. What we see in classical music, though, is much bigger than that. It’s a crisis of long-term sustainability. To give just one example of how that’s true: You can find any cause you like for the present financial problems of orchestras, but when you learn that corporations, foundations, and individuals are less likely to give money to orchestras than they used to be, then you see a larger crisis very likely looming. There simply is less interest — by a lot — in classical music in our culture, less than there used to be, to a degree that calls into question whether classical music institutions can be sustained at the level they’re at now. A question, I might add, that for years has been asked privately inside those institutions.

As for the bubble, you originally said — very definitively — that you were talking about a bubble in the growth of orchestras in the 1930s. That this had been unsustainable, because it was funded by the federal government, and that the orchestras created this way quickly disappeared. As I showed, using a source we both respect, this couldn’t have been true. If you now want to change the subject and talk about the really, really well-known bubble in orchestra expansion in the 1960s, God bless you, may you thrive and prosper. But you’re shifting the discussion from a place where your position is unsustainable, without saying that you’re doing it.

And Grant and Hechinger vs. your impressions of the FMP. Yes, what the FMP did is a matter of public record, but its impact on the larger orchestra community is a matter of interpretation. G&H were on the scene, and so possibly have some authority to interpret what they saw differently from the way you interpret what you read about.

I’ll agree with you that there is a difference between an Orchestra crisis and an overall Classical Music crisis, and I’ll grant you that a financial crisis is different than a legitimacy (popularity?) crisis for Classical music. But I think your talk about the growing (and relatively popular) new music (or alt-classical) culture simply shows there’s a crisis of the traditional ensembles, not of the field as a whole. You can’t expect me to make those distinctions in what I might mean by a “crisis” without understanding how your definition is also selective.

We might take note that charitable giving has been increasing since the recession and that giving to arts organizations have increased faster than the average. While it’s yet to be seen how much of that will filter into the SOBs, I’m not sure how much we can rely on giving studies done during the recession years.

Yes, and I referenced the the Rockefeller/Ford years and the 90s boom: “It’s actually a similar to the economic bubble that happened during the Rockefeller/Ford funding years (and to a lesser extent the 90s boom). In both periods there was rapid expansion” Point was, there was expansion in all three periods, and none of it was sustainable.

See, I actually agree with that, but for different reasons–or rather, I think the cause is less directly related to any inherent lack of interest in classical music so much as with a changing ethnic demographic, non-European-Americans have been building orchestras (e.g. New York Arabic Orchestra, Michigan Arab Orchestra, Seattle Chinese Orchestra) that have more to do with their own cultural histories. The explosion of non-Western Orchestras in the past 20 years is simply a reflection of growing ethnic communities and the increasing aggregate economic power they are starting to have due to that growth.

Given that the White demographic is aging much faster than the population of the US as a whole, we have a younger demographic that’s inherently not Euro-American and have much less interest in Euro-American art forms.

I see many problems with the Grant and Hettinger source, to be frank, and as I’ve recently acquired a copy of the Pierre Key Music Year Book from where the authors got their numbers for the orchestras my thoughts were largely on the mark.

There is no consistency in the list of orchestras provided in the volume–there are a number of WPA orchestras included in the “private orchestras” list despite the fact that they editor has given us a list of WPA Orchestras in its own section. The editor also includes organizations which are not active as well as subsets of other organizations which are already on the list elsewhere. There is even one University Orchestra on the list though the editor also has a separate section for University Orchestras The smallest ensemble listed is a 15 player string group (as I recall) which brings into question why would Grant and Hettinger choose to leave out of the count the 36 (which is erroneous–there were 48 at the time) much less the 110 concert orchestras of the WPA.

Had the total [adjusted] number of 158 WPA orchestras been added to the 84 private orchestras formed during the 1930-1937 period, we’d have a far larger percentage of orchestras formed. As it stands, I think we’ll have to question the accuracy of the list in the Music Year Book (not to mention the Grant and Hettinger book).

The impact that the FMP had is up for debate as most anything is, but when we don’t even know what orchestras existed when, and how and when and why they failed, but it’s interesting to note that another observer from the same period (as well as the editor of the Music Year Book Grant & Hettinger gather their orchestras in existence data from) said this in that very same work:

What’s ironic is that most of the entrepreneurial initiatives that you advocate here, were being done by the FMP orchestras (but not the private orchestras). And many of the things that you criticize in current orchestra culture were the very things the private orchestras were doing back then and that Sokoloff was intent on changing with the FMP groups.

Like you, I attended school and was part of the Classical music scene in the 60’s. Lots of TV shows had classical music.

Also, why pay players of acoustic or electro-acoustic when synthesizers are so much cheaper.

Greg,

Thanks for continuing to articulate so well the issues surrounding classical music’s place in American life. I am old enough to remember when a classical music segment was a regular feature on such TV shows as CBS Sunday Morning. I am always so heartened when classical musicians take the time to go into schools to connect with students through performance and conversation. Such events make a difference. Sadly, I don’t think this is as easy to do as it used to be. Thank you for noting many ways classical music can be promoted and also for highlighting musicians who consider outreach as important as performance.

Thanks back to you, Jim. We’re all in this together.

I wonder how you define “crisis”. The industry has been in hardship from the 90’s, true, but that doesn’t equal “crisis” to me – there was still means of survival for most orchestras, albeit a struggle. People were giving and orchestras were playing. The “crisis” – which to me means orchestras started folding, began believing they could no longer survive, labor disputes ensued, etc – is relatively recent.