Here’s something I’ve mentioned on the blog before. Also something I assign in my Juilliard course on the future of classical music.

But it’s worth showing you again. Back in the 19th century, pianists improvised preludes to everything they played in recitals. Preludes either simply to lead into a piece, or maybe also to make a transition between one piece and another.

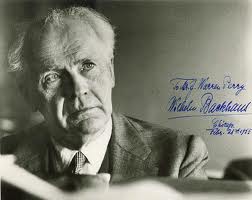

This survived even into the 20th century, into the age of recording. And Wilhelm Backaus — a great German pianist of the old school was doing it as late as the 1960s. (He was my introduction to late Beethoven sonatas, which I had with him playing on a treasured LP when I was in high school.)

So here he is improvising a prelude in 1969, on the last recital he ever gave. First you hear someone saying in German that Backhaus isn’t well, that he won’t play the next piece listed on the program, Beethoven’s Op. 111. Instead he’ll play a short Schumann piece (“Des Abends,” though the title isn’t announced.). Which he then plays, so beautifully, with a touching prelude improvised to lead into it.

So here he is improvising a prelude in 1969, on the last recital he ever gave. First you hear someone saying in German that Backhaus isn’t well, that he won’t play the next piece listed on the program, Beethoven’s Op. 111. Instead he’ll play a short Schumann piece (“Des Abends,” though the title isn’t announced.). Which he then plays, so beautifully, with a touching prelude improvised to lead into it.

See what you think. For me, the prelude settles my mind, prepares me to listen. And puts Schumann in the loveliest of frames. I wish pianists did this today.

Of course, the tradition of “preluding” is not a vestige of the 19th-Century, but was-well accepted in the Renaissance, especially the lute tradition, and Baroque eras. Preludes were published for those less adept at improvising, (J. Hotteterre-L’art de prélude) as well as in some cases, simply as a vehicle for a composer to capture his or her own creativity. L. Couperin, Rameau, É.J. de la Guerre, and others. Backaus’s offering is indeed touching. If he had written out his preludes, would they still be “preludes”? Do you think his “improvisations” were not prepared in advance?

Music is integral and has an absolute time and place. The performer is always responsible for the sound in the room, listening for the response of the instrument to fingers and lips and the reaction of the room and audience to program. It is not a great gap then to deciding the notes, and this has been common practice throughout musical history.

I would argue that improvisation and composer/performers have been a part of every Golden Age. It was only when affordable factory instruments permeated the middle class in the late 19th Century that the schism between professional performer and composer became hardened, until today when any deviation from the printed instructions is judged to invalidate an entire piece.

Musical dynamic comes from establishing expectations and then surprising – so NOT knowing what comes next is an essential part of the experience, and it is best when the future knowledge is double blind. It is rare (if ever) when a note perfect interpretation of standard repertoire moves me so much as an improvised cadenza, a performance fresh from a workshop with the composer which transforms the praxis, a composer performing their own piece or a long form spontaneous composition.

For example, I heard Harry Bickett breathe new fire into the always enjoyable Brandenburgs with a display of spontaneous harpsichord bravado that made the whole set of six memorable evening. The next season he let Rachel Podger free reign in a Vivaldi Concerto and she rocked the house in the manner of Europa Galante or The Venice Baroque Orchestra, who are steeped in the aural tradition of the Red Priest.

Thomas Ades engages in all stages by performing, conducting and instructing and it shows. This is not necessarily popular with the score slaves of elite Manhattan orchestras; but I heard a brilliant program in the Music Mondays series which included the Maestro on piano and baton, and SpectrumNYC recently hosted the first public appearance of a string quartet formed to play “Arcadiana” following a workshop with the composer and it was intoxicating.

We also presented Ramin Arjomand, a pianist who is developing a long form classically based improvisational piece equivalent to Keith Jarrett’s solo concerts. This is the vanguard of the third wave, with neo-Baroque fugal and rhythmic elements, Romantic arpeggiation, dense 20th Century harmonic structures and at times sparse silences like contemporary Northern European composers as well as frequent quotations.

Unfortunately, appreciation of improvisation suggests knowledge of the history as in Jazz; but the aging classical audience has been programmed to predictable repeat performances and younger potential patrons don’t have the attention span to absorb 400 years of history nor sit still for a 65 minute sonata.

Australian pianist Geoffrey Lancaster preludes in recitals and it’s an absolute delight.

I enjoyed listening to that Prelude. In London there is a young generation of classical musicians who can improvise in a classical style which is wonderful. I recently had a work of mine performed where all three improvised. In one section the three improvising together sounded like Pousseur in places.

This is such a welcome change, as at one time improvising in classical music seemed to be either bad jazz or avant-garde ‘fire in a pet shop’ noises.

I’ve started doing this after intermission and it’s one of the most liberating things I could have added to my concert experience…for me and the audience. Thanks for sharing!