This stopped me dead in my tracks the Sunday before last, when I was browsing through the New York Times.

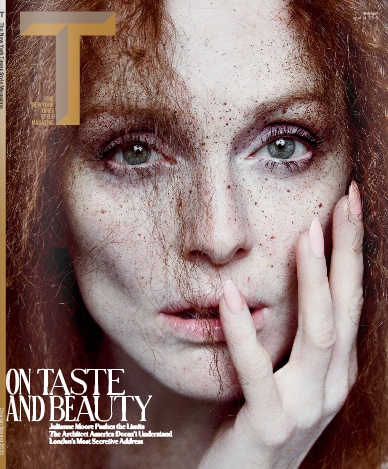

It’s a photo of Julianne Moore, on the cover of T, the Times‘s fashion magazine. Arrestingly beautiful, I thought. And certainly not an old-fashioned, clear and simple kind of beauty. Hair everywhere. And all those dark spots. Spots of dirt, my wife and I first thought. But in fact they’re some of the freckles that (as Moore says in the interview that goes with the photo) shower her body.

Contemporary beauty. Layered, deep, not entirely reassuring, grainy, with an undercurrent of focused visual noise. Elements of edge and danger.

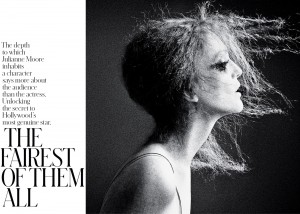

There were more photos:

And see how these photos are offered as exemplars of beauty, without any caveats about upset, dirt, or anything even a little bit strange. Moore is the fairest of them all. And the theme of this issue of the magazine, we’re told on the cover, is taste and beauty, with Moore’s photo as exhibit A.

So now we’re in a world very far from what we usually see in classical music. In classical music, beauty in its older forms still reigns. When we say, as we so often do, in conversation, in marketing blurbs, in classical music advocacy, that a masterwork is beautiful, we mean that its beauty is radiant and pure. Untroubled. The beauty may be threatened. The people who have it may meet a tragic end. But the beauty itself is never questioned. It’s simply…beautiful.

And we glory in that. But that’s not what our culture does now. The threat to beauty, the complexity of its existence, of its unfolding in the midst of many things that aren’t beauty (in the older sense) — all that has mingled now with beauty itself, so beauty now can be dangerous, unsettled, unclear, ambiguous.

As it is in lyrics I quoted years ago, in the blog, from Björk:

Emotional landscapes,

They puzzle me,

Then the riddle gets solved,

And you push me up to this

State of emergency,

How beautiful to be,

State of emergency,

Is where I want to be.

(From “Jóga,” on the Homogenic album.)

We need to understand this. I read so many eager hopes for classical music: strategic plans, ideas for advocacy, strategies for bringing classical music to a wider world, all based on the sweet but naive notion that classical music speaks for itself, that its power and (yes) beauty will sweep away nearly anyone who has a chance to hear it.

This might be called the “we love it so much” strategy. Because we love it, you will, too. Very sensibly, the people who — with all their hearts — buy into this understand that the presentation has to change, that we have to be less formal, more embedded in the world around us.

But what’s almost never talked about are the people we want to reach. Who they are, how they think, what their culture is. T magazine drops us, with no warning (because in its world none is needed) right into the coldest water in the deepest part of the pool. This is what the people we want to reach are looking at. This is what’s normal in their world. (Those photos weren’t in some obscure art or fashion journal. They were in the New York Times.)

And for the most part we don’t offer anything similar — anything contemporary, anything that fits the world the people we want to reach are in. Album covers for Naive’s Vivaldi series are exceptions:

And also ads on the sides of New York buses, from the Met Opera. And there are others. (I’m talking about mainstream classical music. When get to the indie classical world, then contemporary images are far more common: Sally Whitwell’s album covers, or the recent one from Lara Downes. (To cite just two of our guest bloggers here.)

Of course, we’ll hear that classical music doesn’t compete with fashion (T magazine) or movies (Julianne Moore). Or that it offers, like gentle rain on a junkyard, an antidote to horrid modern culture.

But in fact we compete with everything out there, because people who spend time with us choose to do that, when they could have spent time with something else. And the people we want to reach don’t think — no surprise — that their culture is horrible. As in fact it isn’t.

Besides, who in their right mind — in the world outside ours — would plan strategies to reach new people, without learning who these people were? When I was an editor at Entertainment Weekly, we surveyed our present and potential readers, learning everything about them, even what vegetables they liked. Not the same ones, it turned out, that readers of Rolling Stone preferred. Vegetable research sounds a little silly, and may, for all I know, have been overkill.

But there it was. We tried to learn about the people we wanted to reach. If we in classical music don’t do that — and we don’t need high-priced research; just open eyes and common sense — our bright and optimistic strategies may well be doomed.

Well said, Greg.

Unfortunately, the industry isn’t going to listen. If classical music organizations started asking what new audiences wanted, they learn that they couldn’t just keep telling the world how wonderful they were and producing self-aggrandizing, self-important, self-flattering marketing materials that have no grounding in contemporary audience’s expectations.

The promotional materials most classical organizations produce now are hand mirrors they can hold up in front of their faces to reflect the beauty they want to see and screen out the freckly worlds they’d prefer to ignore.

I often think it’s innocent on their part. They just can’t perceive the outside world. Or understand how different it is from what they think and do. But it does end up being a self-serving belief. “We’re fine! We’re terrific! We just have to figure out how to show that to others.” Though there”s one crucial problem: self-serving as this naiveté might be, it doesn’t actually serve these classical music organizations, because it won’t help them get a new audience. In fact, it will stand in the way.

Why do you always express yourself so polemically – so melodramatically? I barely recognise the industry I live and breathe from your descriptions of it.

Exactly my point, Ted. The industry you live and breathe in doesn’t recognize itself — doesn’t understand how it looks to the wide world outside it. Takes for granted a lot of things about itself that need to be seriously questioned. I’m sorry if that seems harsh to you, but the decline of classical music as an enterprise in our current world is a pretty strong demonstration that I might be right.

I think what popular culture is saying about beauty and taste is that it isn’t limited to a definable list of attributes. They’re saying beauty isn’t even KNOWABLE for any given person in a radically individualized, polyglot society such as ours. Your words are beautifully written… to a degree I can’t fully appreciate. But the classical establishment seems to be saying, if we can’t proscribe what beauty is any longer, we can at least cater to the ones that can afford to finance it… hence the perception of an elite is self-fulfilling and not necessarily derogatory. To break this cycle, I hope the union will embrace the phrase “responsibility to build future audiences” and managements/governing boards, “wild and crazy”. Otherwise experimentation by those with the best resources is limited and extremely slow.

The big question you raised for me is, can the artistic taste-makers who prop up the high standards relinquish those standards long enough for a new audience to take root? Put another way, can the taste-makers shift their sense of beauty or quality from an art-centric POV to a new-audience-centric POV? I do it by recognizing that art WANTS to belong to everyone and an audience that connects on its own terms IS quality art-making.

I remember your post perhaps a year ago about attending concerts with the point of view (POV) of someone new and finding it very unconvincing… not by the programs but because the performers weren’t convincing. In part you meant body language but largely you meant the musical climax was dull or otherwise missing. I agree that permission to exude over-the-top musicianship in America seems to be reserved for soloists. But our trade is in the intangibles; as in, let us somehow communicate WHY we love to play what we are playing. Exaggerate the details and characters. Heighten the drama. Shape EACH phrase so its climax and role are relative and clear. Conductors don’t always give us that in an orchestra. But without tension & release, we’re wasting the time of our veteran audience and failing to convince any new audience this is MORE than just beautiful music. The musicians MUST lead!

Well, I can return the compliment. Your words are beautifully written. I think we’re in a promising situation, even if the big institutions seem to be hanging on to their old ways. But there’s so much change. Even inside the big institutions, there’s lots of private acknowledgment of how badly we need change, as I wrote in my post about the coming tipping point. And finally there’s generational change — a new group of younger people coming into power. They see things differently. I realized in the past few months that the very problem I’m describing — the cultural gap between classical music and the rest of the current world — contains its own solution. Since the outside culture is, after all, our culture, people in classical music share it, even while they function inside the classical culture. As time goes on, more and more of them start doing inside classical music the things they see in the outside culture, simply because it feels right to them. And so things change. We still need that larger tipping point, but it’s coming.

“permission to exude over-the-top musicianship in America seems to be reserved for soloists.” What? You should move to Australia! We have an extraordinary orchestra here that you would love, the Australian Chamber Orchestra. Here’s a splendidly over-the-top performance they did of Janacek’s 1st string quartet, “Kreutzer Sonata” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TlNBvvsMr-g The arrangement works splendidly, don’t you think?

Sally, I’d LOVE to come to Australia! The ACO sounds AMAZING… thanks for sharing that great clip! I love that they stand and play chanber music style (no conductor). This reinforces the elements of dance and gesture within instrumental music. The risk of making the music matter is slightly different from the original. This is not only a welcome refresh of the famous work, but they negotiated an excellent balance between inherently personal and larger expressions switching between solo and tutti this way. I specify the same switching when string orchestras perform my sextets. I’ll look for more videos from ACO!

Btw, was that a narrator waiting his turn off sides? I like to see and create such context-setting: It maximizes the impact for most audiences, new or veteran.

Here’s a tribute to the ACO. I was talking to someone high-ranking at a well-known British orchestra, one that can pride itself on its Beethoven performances. He said they’d been touring Australia, and played the Fifth Symphony, and thought they’d done it wonderfully. The next night the ACO was doing it, and people from this orchestra went, with a little skepticism that the ACO could ever match the previous night’s performance. But they came away thinking the ACO had done it better!

They really are marvellous at just performing this incredible repertoire with sensational energy and complete commitment. You could also look up something they recently did called “The Reef”. Their Artistic Director Richard Tognetti is a keen surfer (I’ll leave you to add two and two together!)

Sally, the ACO comes to the US pretty regularly. I don’t know if Greg himself has seen them, but plenty of other American critics have, and the group generally gets quite good reviews here.

For whatever reasons, the ACO has not caught fire with audiences here the way they have at home. They seem to impress the folks who hear them, as far as I can tell, but they haven’t become the stars they are in Australia, even though their work may deserve it.

I don’t know if that’s because of marketing failures by the organizations that present the ACO in the US, wider classical music marketing issues, or (most likely, I think) it’s just that much harder for a group like the ACO to make itself known to people in the enormous, expensive US media marketplace(s) than in its home country of only 23 million people where the bulk of the classical music audience is concentrated in only four or five cities.

I haven’t seen them, Matt, and very much wish I had. Anne raved about them when they last came to Washington. Somehow when they come to NY I’m in Washington, and when they came to Washington I was in NY. When I was in Australia, they weren’t performing. Very sad that I’ve missed them.

So you do know about them! Greg, do you have any thoughts as to why they might not have caught on in the States quite the way they have in Australia? From the quality of their work, one would expect sold-out houses and US imitators.

I don’t think they’ve toured here much. That’s a partial explanation.

But then I don’t find that information on even the finest classical music innovations travels nearly as much as it should. So it’s very possible many people don’t know about the ACO. Also, they may not do much to publicize themselves in the US, which might be a reasonable choice, if they don’t come here much. I could imagine them making a huge push for audience and attention, selling videos, recordings, merchandise, whatever. But maybe they don’t think that way.

Imitation is difficult, especially when you’re imitating a group whose greatest strengths are intangibles — the excitement of their playing. One US group that’s worth looking at is the River Oaks Chamber Orchestra in Houston, which works on a very different model. Only performs in Houston, and cultivates an audience there. Not at all a national perspective. Which, finally, is a more daunting challenge in the US than in Australia, because we have a vastly larger population, and many more cities you’d need to go to.

Parallel example: the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment has done wonders to cultivate a young audience in London, but I doubt many people in the US (or at least among people who don’t read this blog) know that. And the OAE doesn’t make a point of touring here, or of publicizing in the US what they do.

The OAE makes it to New York about once a year, if only for a gig at Mostly Mozart; I don’t think they tour more widely in the US much unless they’re traveling with a well-known soloist.

As for publicizing activities in the US, my guess is that both the OAE and the ACO would say that that’s the responsibility of the presenting venues; after all, they’re just popping in and out of any given media market.

If, say, the ACO were to undertake the sort of campaign you’re imagining, it would probably be good for classical music in the US overall, but it would cost a lot of money that they probably can’t spare.

As for the cultivation of young audiences that the OAE is doing in clubs and other places, I think that’s the kind of longer-term project that a group can only undertake on its own home ground.

Very good points, everything you say. So no blame to these terrific groups that concentrate on their home turf.

Still, the options for partnership with touring venues are very tasty. The Washington Performing ARts Society, now under fine new leadership, could invite the OAE to replicate its Night Shift in Washington. Or bring the ACO in for a residency, maybe in conjunction with a music school in the area, Peabody or the University of Maryland.

And the OAE and ACO and other groups could look for opportunities like that. Wonder if I can broker something?

Maybe you could broker something – though that would, of course, make any coverage by the WashPost problematic …

The final judges of any potential conflict of interest would be the Post’s editors, who of course would be consulted.

Beethoven’s Opus 135 — or just about any piece composed by Beethoven.

This isn’t a helpful way to continue the discussion, in effect by waving flags. You wave the Beethoven flag (easy to do), I wage the Björk flag. And we’ve proved nothing.

Of course Beethoven’s music is both beautiful, and deep. And, because Beethoven is a great artist, there’s texture to his beauty, a mixture of things that can be unsettling. There’s a famous passage in E.M. Forster’s novel Howards End, which I’ve often quoted, in which a 1904 listener (in her 20s) admires the Fifth Symphony precisely because it has darkness and danger in it. And look at Bach — a dark view of earthly life, nestled next to and within his beauty, a view that comes from his Lutheran religion. Or Mozart — Cosi fan tutte offers beauty right next to the unsettling idea that love can be undermined at any moment. The E major trio in the first act is almost unbearably beautiful for that reason — three people wishing godspeed to the lovers of two of them, when the love affairs are about to unravel very painfully, and the third person has schemed to make that happen. At the height of the piece, the flutes join the orchestration on a shivery diminished 7th chord, on the word “desir” (desire). Suggesting that desire, love, beauty, all those things are badly fraught.

So the classical masterworks aren’t themselves a problem. Of course art of the past still talks to us. The problem in the classical music world is first that we have too much art of the past and not enough of present-day culture (though that’s changing). And then secondly that we too often talk about the art of the past as if it was simplistic — “beautiful,” “masterworks,” “beloved,” “profound,” “transcendent.” Thereby smoothing out their kinks. It’s not at all hard to present older music from our current perspective, and when that happens, the results are often dramatically powerful.

If “the people we are trying to reach” continues to be narrowly defined as “those who read The New York Times,” there will be no way out of the elitism that is causing the decline in audiences for music whose “beauty” is easily discerned by people who have never set foot at Lincoln Center. The definition restricts not only the audience for performances and recordings, but also the children who can have access to music instruction of any kind.

You’re jumping to conclusions here. If I defined the people we want to reach as people who read the NY Times, I’d leave out most people under 40 (who mostly don’t read any newspaper). I was using the Times to demonstrate what’s current in our culture. You’ll find the same culture more or less anywhere you look. The Times was only an example of it.

Beauty untethered from the other two elements of the classical triad – truth and goodness –becomes just one more item subject to contemporary whims. The attributes of beauty – harmony, proportion, integrity, clarity – can encompass a very wide range of concrete expressions. What it cannot survive is a radically subjective redefinition that demands that older concepts of beauty be replaced – rather than expanded – by newer ways of understanding the good, the true and the beautiful. When objective criteria are supplanted with a purely subjective judgment that can change with the fashions of the day, we have lost a concept of beauty that is true and good and that exists in itself, rather than in our fickle assessments.

As C.S. Lewis wrote, observing that the primary feeling aroused by beauty is not pleasure, but longing: “[T]he books or the music in which we thought beauty was located will betray us if we trust in them. It was not in them, it only came through them; and what came through them was longing.”

You remind me of the critic John Simon, who on a panel I chaired a couple of decades ago said — with brave but somewhat sad defiance — that he could _prove_ that his controversial reviews were correct, that any person open to reason would have to agree with them. What would you make of the dramatic shifts in the concept of beauty that have come in the past? Abstract art, atonality. Wagner, whose music was in its time “proved” (by conservative critics) to be incoherent. Etc. I’d love to see your critique of the Julianne Moore photos, if you have one. And of the Björk song, too. Best to be specific about these things, and not utter too many grand generalities.

Greg – your understanding of beauty, from the examples given in the photos and Björk’s lyrics (which lack context since I’ve never heard the music that sets them) seems to lean towards the transgressive – and is very typically contemporary in that regard. With respect to the photos, I would say that the judgment about beauty depends on whether one regards Ms. Moore as an abstract canvas or a human person. As a canvas, they are beautifully lit and composed. But they do not in any way enhance or celebrate her natural womanhood, rather the opposite, presenting her as an object.

With regard to atonality, there’s beautiful atonality and there’s not-beautiful atonality. The difference lies in whether the composer was able to achieve a work with its own harmony, proportion, integrity and clarity. Messiaien would be one composer who seems to have found ways to do this consistently whether his language is atonal or just hyper-extended tonality. The same is true, I think, of Berg.

We have to speak in “grand generalities” (you do, too: “so beauty now can be dangerous, unsettled, unclear, ambiguous”) because we’re discussing a philosophy, not so much individual works.

I do not share your view that the New York Times grants canonical status to this or that trend in perceptions of beauty. I do agree with Simon that an understanding of beauty is accessible to reason, though it certainly does not end there.

Without reason we cannot know beauty and your commenter Rick Robinson makes that very case: (“I think what popular culture is saying about beauty and taste is that it isn’t limited to a definable list of attributes. They’re saying beauty isn’t even KNOWABLE for any given person in a radically individualized, polyglot society such as ours.)

If beauty is not even knowable, why should I read anything you (or other like-minded observers) have to say on the subject?

We are soaring into outer space here. I’m talking very simply about what mainstream taste is like these days. The New York Times, God save the mark, has no canonical status in any definition of beauty. It’s just — I wonder how many times I’ll have to say this in comment replies — a good indicator of educated mainstream taste. Nothing more, nothing less.

“But they do not in any way enhance or celebrate her natural womanhood, rather the opposite, presenting her as an object.” Well, I disagree. And what a thing for you to say! You are, I take it, the guardian of “natural womanhood.” whatever on earth that may be? Perhaps related to the “ewige weiblichkeit” of Goethe fame? Sounds like a concept wafting in from another time. A time when men defined what women were. I thought we were past that. But I guess not all of us are.

Leaving “natural” womanhood out of the discussion, I’m impressed, if that’s the word, by how confidently you take charge of defining what’s what. You say with utter confidence that no person shows in those wonderful photos, only an object. And yet I see it completely differently. From the moment I glimpsed the cover, I thought, “What a gorgeous woman. What a gorgeous person!” I saw full, rich personhood. I suppose you’re now going to say that my perceptions have somehow been debased. Or how _will_ you deal with the simple fact that people see things differently?

Well Greg, if all you are doing is pointing out what mainstream taste is like these days, you’ll have to cast a wider net than the pages of the New York Times, whose readership is a small – if elite – subcategory of people whose tastes in fashion and art tend towards the transgressive.

I am not the “guardian of natural womanhood” and I am not attempting to “define what a woman is” – those are red herrings. By natural womanhood I mean simply her attributes as a woman in the way nature itself formed her into an individual female human being. That third photo seems more suited to a periodontal exam than an appreciation of the shape of her mouth, for example.

People see things differently for all sorts of reasons. One such reason might be commitments to incompatible philosophical positions. I believe that’s the case here with our disagreement. I hold that the good, the true and the beautiful are transcendental values, all of which are convertible to their counterparts (i.e. what is true is beautiful and what is beautiful is good, etc.) and that these values can be known through the exercise of natural reason (even if this discernment is sometimes a long and difficult endeavor). This may be the source of your remark about the “confidence” with which I “take charge of defining what’s what.” I am not taking charge, I am instead recognizing a truth – even one that may lie outside the realm of my subjective impressions.

You appear to be skeptical of making such claims. Perhaps we’ll just have to leave it at that.

There are various mainstreams we could talk about. One would be, let’s say, the NASCAR audience. Very transgressive, actually, or at least a large subset of it is. Tattoos galore. In fact, the spread of tattoos is a good measure of the growth of transgression in mainstream taste.

“Elite” is a fascinating word. If we’re talking about an audience for classical music, that’s bound to be upscale. The NASCAR audience (or the country music audience, or the evangelical community — to name various largish parts of the US mainstream) — these audiences aren’t likely to be where anyone would go to recruit new classical music listeners. Whereas attempts to go to the young, upscale, educated audience, including people with tattoos and piercings — the indie rock audience would be one way to quickly label it — have been spectacularly successful.

I love it, by the way, that you see the Times as elite and transgressive! I’ve been reading it for decades, and the way it’s normally thought of by transgressive people — or simply people with contemporary taste in art and culture — is that it’s way behind the times. (No pun intended.) So the outbreak in the last decade of contemporary art and culture in it is quite a revelation. Suggests that these things have broken out far more widely than most of us know. I’ve seen them covered even in small-market newspapers, when I travel. I once went to a fabulous art show — way off the old-fashioned mainstream conception of art — because I saw it written up in the New York Daily News, which is far from elite.

If you look at hiphop — not an elite artform, doesn’t have an elite audience — you’ll find all kinds of advanced and transgressive things going on. Likewise in many pop genres, metal for example (about as nonelite as a pop genre can get). Or look at Richard Florida’s description of contemporary nightlife in The Rise of the Creative Class, either the old or the new edition.

Or just hang out in coffeehouses in any large city, or any college town.

As for natural womanhood, you’ve defined your position very well. As you see it, your tastes are laws of nature. Good luck with that. A lonely position to hold these days, I’d think. That in itself doesn’t mean that you’re wrong, but the conversation between you and anyone who sees things differently doesn’t seem like it could be very productive. I’ve had wonderful times discussing art and culture with people who see things differently from me. We end up learning from each others’ points of view, and understanding that these views come from different life experiences, to name just one factor. So then we end up with a larger understanding of the world than we started with.

I’m not sure you could do that! Because you start with the belief that you’re right, and that other views aren’t in accord with nature. Would be lovely to see you discuss natural womanhood with a Muslim, who might say that a headscarf or even a full veil is a very high-ranking grace of natural womanhood. Or, if you could travel back in time, have the discussion with a Chinese of generations past, who thought the same of bound feet. Or someone in Africa, saying the same about distended lips. Everyone believing that their views were grounded in nature.

Greg, you actually told him he reminded you of John Simon??

Dude, them’s fightin’ words …

😉

Thanks so much Greg for the shout out re my album covers. I am super proud of them!

I think the solution is pretty simple actually – artists need to think harder about how their recordings are put together in every single way. All they need to do is to decide to take some responsibility for how their art is presented to the world, not only as an exciting and coherent listening experience but also visually and conversationally. Yes, conversationally, by which I mean they need to get better at communicating through the music AND about the music.

Actually, I might just write my own post about this. Stay tuned!

De gustibus non est disputandam—