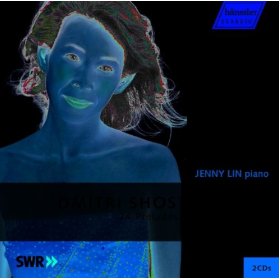

I was listening to my friend Jenny Lin’s strong recording of the Shostakovich piano preludes and fugues, and it made me think about my graduate study in composition at the Yale School of Music, from 1972 to 1974. And how Shostakovich was a nonperson. We never talked about him. He was bad. He wrote tonal music.

I was listening to my friend Jenny Lin’s strong recording of the Shostakovich piano preludes and fugues, and it made me think about my graduate study in composition at the Yale School of Music, from 1972 to 1974. And how Shostakovich was a nonperson. We never talked about him. He was bad. He wrote tonal music.

Likewise Benjamin Britten. Like Shostakovich, he didn’t count. In 1974 (after I got my degree) Britten’s last opera, Death in Venice, played at the Met. It overwhelmed me. I saw the error of my (and Yale’s) ways. (Funny: I’d sung in Peter Grimes, in a Yale production, doing the leading baritone role, Captain Balstrode. But somehow the quality of that piece — plain to me now — escaped me.)

The music we cared about: modernist music. Berio, Ligeti, Cage, Stockhausen, Carter, Mario Davidovsky (who came to teach at Yale). I gave a vocal recital, and sang music by Ligeti, Morton Feldman, and George Crumb. Somehow tonal works by Stravinsky and Bartok were allowed in our pantheon. But not Copland, Prokofiev, Britten. Or Shostakovich.

Though I didn’t realize it then, those were bad days for new classical music. Though I love a lot of modernist music, including the pieces I sang, and of course Webern (a composer who reaches a deep place in me). I think this music should be revived, promotoed, maybe in pop music contexts. And, I’d think, at art museums.

But the stress on modernism — and exclusion (at Yale, and other prestigious places) of masters like Shostakovich — did so much harm.

Oddball footnote: If you follow my link to the Amazon download of Jenny’s album, you’ll find the cover rendered as a photographic negative, with colors reversed. Weird!

We loved hearing her [Jenny Lin] alternate selections from The Well-Tempered Clavier and Shostakovich’s “24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87” at the Bach Festival at Baldwin-Wallace in April. So insight-provoking for many of us in the audience.

She’s a thoughtful, powerful pianist. Her recordings can be revelatory, about repertoire, among other things. Her Mompou CD, for instance, or the one of the Bloch piano concerto, which (to my ear) sounds like a film noir score.

She’s a phenomenal virtuoso, too, something often overlooked because she’s labelled a new music specialist. She’s played some pieces of mine, which you can find on the music page of my website, http://www.gregsandow.com/music.

That’s simply tragic how Shostakovich could be overlooked so easily. Was the reason really that his music is too tonal, or was it that it’s too accessible? Personally, Shostakovich is what inspired me to study music in the first place – yet it’s forbidden to learn his music because, although effective, he composed with the wrong toolkit? I would gladly trade my courses in twelve-tone combinatoriality for lessons in how to write music as moving as the Trio no. 2. (It’s also ironic he would be considered “too tonal” considering that his modernist leanings nearly cost him his life.)

There’s a kind of duality at work here, though, Simon… there were no “soviet’ composers writing atonal music (it wasn’t permitted), and ergo there was no soviet atonal music. So tonality was an automatic built-in feature of music written in the USSR (and ditto in Poland and other outposts of communist thinking). It’s hard to say whether DSCH’s music was suppressed in the USA because it was ‘tonal’ or because it was the work of a soviet composer… because these two things were effectively one and the same thing.

Perhaps I am too cynical, but I can’t somehow see post-McCarthyian America brimming with joy over works like ‘”The Oath to the People’s Commissar” or “October” – or their composer either.

I don’t think Shostakovich’s music was suppressed in the US. Nor was Prokofiev’s. Or, for that matter, Kabelevsky’s (hope I’m spelling his name right) or Khatchaturian’s. Shostakovich was just disapproved of by the modernist composers, who had tremendous influence on what got taught in leading universities and who got hired for major faculty positions.

Or was it a bit of Cold War-era jingoism that made the composer of the “May Day” and “Leningrad” symphonies a composer who could not entirely be taken seriously?

John, I never ran into even a trace of any feeling like that. Certainly not in my own case. As an undergraduate, I majored in political science, with a specialty in Soviet affairs. I had nothing but the greatest interest and sympathy for everything Russian, and to the extent that I thought about Shostakovich at all, didn’t regard him as a Stalinist. We didn’t know then where he really stood, but I thought of him as a victim of Stalin even then, not as a perpetrator of Stalinist ideology.

Britten was gay. Shostakovich & Prokofiev were ‘soviet’ composers.

What did you *expect* they would allow Yale? 😉

Don’t think these things were considerations. The singers at the Yale School of Music sang Ned Rorem songs, for instance. And Shos and Prok were studied in music history courses. The ideology I’m talking about involved only composers, and was about modernism, not sexual identity or the Cold War.

How could we explain permitting Stravinsky (the emigre Russian who typified the flight from the Evil Empire in pursuit of creative freedom) but not permitting DSCH? Both born before the Revolution – one stayed, one didn’t. DSCH’s location in the USSR could surely be the only rationale?

Stravinsky made the cut because (1) he’d been a revolutionary, writing complex, dissonant music of the kind the modernists liked, and (of course) (2) he’d converted to 12-tone writing. It’s sweet, in a way, that because of those two things, a modernist-oriented theorist, Alan Forte, could do set-theory analyses of Stravinsky’s harmony in his neoclassic works, using (Forte) the same tools he used in analyzing Schoenberg or Berg. The same tools could have been used for Britten, but as far as I can remember they weren’t.

I take the point that Stravinsky was blackmailed into writing dodecaphonic music by the coterie who ran “new music” at the time. Almost all of his late serial works are sad failures. I wonder if that was why Prokofiev decided to return to the USSR?

However, it didn’t always work that way. Lourie’s USSR-written works were extreme and uncompromising – but he started writing mush when he went to America.

Alex Ross’s book, “The Rest is Noise”, one of the best narratives of music in the 20th century that I have encountered, has much to say about the postwar attitude toward new music and the supposed need to denounce anything that was remotely tonal. Indeed, there is one chapter entitled “Beethoven Was Wrong”.

Like you, Greg, I lived through that time but always managed to appreciate the links between Mahler and Shostakovich, Brahms and Schoenberg, and even Bruckner and Varese. Cage, Boulez, Berio, Stockhausen, Xenakis (and others) fascinated me though I never really loved their music (and still don’t, really, though I own and frequently play Cage’s “Indeterminacy” just for the wide range of his one-minute stories (profound to downright hilarious). But I stray. There was indeed a condescending attitude toward tonal music of people like Britten and Shostakovich. Interesting that Brahms was fascinated with the compositions of the young Mahler, and that Mahler and Strauss were equally fascinated with Schoenberg’s atonal works. And Boulez has made a great second career as a conductor performing many of the works he denounced so strongly in his earlier life as a young rebel composer. It really doesn’t seem that the titans had any problems with either C major or tone rows.

People who write of Percy Grainger as the writer of endless ditties know nothing of his musical philosophy or experiments in ‘free music’ (his term), or his some of his earlier work (The Warriors) that contains sections that as Charles Ives-ish as most anything Ives wrote.

I never have understood the need to denounce any of what came before as a way of embracing the new.

Ross points out that sexuality was not a big deal in the reasons people dismissed Britten. His relationship with Peter Pears was common knowledge and his preference for young boys was kept tightly under wraps at the time. If anything, his pacifist views caused him more grief in England, but as you point out, his musical language came into full flower in the age of post WWII era when Schoenberg and the New Viennese School and even Stravinsky were being viewed as terribly outdated.

Leonard Bernstein, in his Harvard Lectures from the early 70s came out strongly for tonality. Granted most of his output was in that style, but he had spent a good amount of time performing music of the post-war composers (including Cage) before arriving at that conclusion. And then came the new tonalists after him . . . (It’s also interesting to see how Berio’s musical language evolved more and more back toward tonality.)

I still listen to Webern and Boulez. Just bought a new set of the complete Webern last week. I like that music, really do. But as I said about others above, I’m not sure I’ll ever love it. And for that matter, I’ve never quite warmed up to most of Britten, but that’s my problem, not Ben’s.

I think that audiences today are adult enough to hear all kinds of music from all kinds of style periods and genres.

Thanks, John. I’m with you in all of that. And, a question — what’s the new set of the complete Webern? I don’t know of it, and would love to hear it. I’m not a great fan of the two Boulez versions, because I think Boulez isn’t romantic enough. Webern, it’s known, wanted dynamic and tempo changes to come out really strongly, and Boulez doesn’t conduct like that. To hear the difference in a very striking way, compare Webern’s conducting of his orchestral arrangements of Schubert dances (included on the Sony complete Webern set) with Boulez’s performance, on the complete DG set. Webern’s performance, a miracle of expressive nuance, seems to me a window into how Webern would have wanted his own music to go. Boulez, in the Schubert arrangements, doesn’t come close.

Sorry, new for me, not new. It was the Boulez on CBS Sony. Different strokes for different folks.

But the bias against tonal composers was not only directed against foreigners. Look at the fate of composers like Menotti and Barber? It seems as though America will never forgive Barber for having the gall to write tonal music – even today he’s sidelined and studiously ignored (with the exception of the Adagio, of course).

Where are his operas performed now? VANESSA is a masterpiece no-one will perform. ANTONY & CLEOPATRA has dropped into a black hole.

Agreed. Just a little plug for the Central City Opera in Colorado which did a very successful run of Vanessa a couple of years back. I’m sure there have been more productions of this and other deserving operas, but Neil, you’re right. The anti-tonal crowd — and I knew them when I was in music school — was kind of the tea party of it’s day.

I well remember a friend studying composition at a well-known university that I will not name, and being told that Ives was off-limits as well.

Even today, in a recent article, Gunther Schuller called composers who were once serialists now composing tonal music “turncoats.” I leave this to others to comment.

David Del Tredici and George Rochberg were the two most famous turncoats. I remember listening to Rochberg’s Third Quartet (the one with the Mahler-like slow movement) in the ’70s, when I was at Yale, and being astonished and inspired.

In the ’80s, when I was a critic, I wrote about one of David’s Alice pieces. I had the score, and commented in some detail, as I remember, on his orchestration, particularly his handling of inner voices. I didn’t know David at all back then. We’d never met, never communicated in any way.

So imagine my surprise when a letter arrived in the mail one day from David, asking if I’d write a letter of recommendation for him. He was being considered for a faculty position at a major school, but some people at the school objected to hiring him, on the grounds that his tonal music was trash, that it was empty, shallow junk. Since I’d said otherwise, talking about concrete compositional details, he wanted me to support him.

There you have a vivid demonstration of how potent the modernist prejudices were. David had to reach out to a mere critic, in order to be hired to teach composition at a university.

I had a serialist prof who believed Ives would have been a “great” composer if he had jettisoned the “useless” tonality. He thought that “Three Places ” (one of my favorites) would have been “better” if he avoided all that tonality. Serialist ideology was almost as unforgiving as Marxiism, or modern day Ayn Rand Objectivism/Anarcho-Liberitarianism. God deliver us from the wrath of the Idealogues.

Well, I was in NYC and we were thrilled to the work of Pierre Boulez, the RUG concerts and all. Shostakovich made a trip to NYC but was not too thrilled (from news reports) w/the Rug concerts. Too bad, but I remember his

15th symphony with its evocation of the history of Western music as a brooding odd masterpiece. And I have been studying these late works in recent years, as I catch up to them. Not really listening at all to most of the 70’s composers except Berio and Poulenc more and more. Also Bussotti a undiscovered wild man but revered in Florence and too little known in the USA. But I am trying to rectify this and present him, Eisler, Dessau and Gottschalk all too little known as well. ArtsPRunlimited, Inc., has presented several innovative production of these figures at the Morris Museum, Landmark Tavern, Snug Harbor and hopefully Newark, NJ as well..

I had the same experience doing a couple of music degrees at McGill University in Montreal in the mid to late 70s. The only time Shostakovich was mentioned was in the context of Bartok’s satire of him in the Concerto for Orchestra. Other unmentionable composers were Britten and Sibelius. Not too surprising as one of the theory teachers had been a student of Milton Babbitt’s at Princeton.

The Cold War did have influence on compositional ideology, though. The US government supported a lot of the European modernists by helping to finance courses at Darmstadt, for example. In the US, the ideology of modernism involved technical and stylistic innovation–these were virtually the only values that mattered. For a time, at least, the most influential composer in the US was Milton Babbitt, certainly in academic circles. The cultural context that Shostakovich had to deal with was utterly different.

I have posted a lot on the Shostakovich preludes and fugues:

Most recently:

http://themusicsalon.blogspot.mx/2012/04/very-interesting-program.html

http://themusicsalon.blogspot.mx/2012/05/more-on-very-interesting-program.html

And more thoroughly here:

http://themusicsalon.blogspot.mx/2011/12/shostakovich-and-fugue.html

Yes!…Jenny Lin is an outstanding pianist. I didn’t hear her Shostakovich Preludes and Fugues – I have Konstantin Scherbakov’s disc for these pieces . Phenomenal! ….If you want to hear more incredible performances from Jenny , get her cd “CHINOISERIE” (if you didn’t yet, of course)….amazing!!! ….

I do agree with you , Shostakovich’s exclusion was also a shame! The “modernism” fashion that took place in the 70’s harmed Classical music in many ways; many great composers weren’t almost even mentioned in those days . Shostakovich suffered a kind of “double censorship” : In the Soviet Union for being “too modernist ” and in America for being ” old fashion” or “too tonal” . thankfully, what remains is the general recognition of a truly “great master”. My perception (i could be wrong on this) is that many great current composers are suffering the same exclusion at some places like Yale ; in my personal view, an also truly great master like Einojuhani Rautavaara could be the 21th century nonperson composer in some circles.

Shostakovich was always one of my favorite composers. Not everything. But most of it. He is sadly underrated in composition circles and overrated in typical classical circles due to his fifth symphony. I write post minimalist stuff. But DSCH is never very far.

Shostakovich is overrated?? What???

Greg …I posted the same comment yesterday …it seems that it got lost. Anyway..i comment again

Yes! Jenny Lin is an outstanding pianist. I didn’t hear her Shostakovich Preludes and Fugues ; i have Konstantin Sherbakov’s Cd for these pieces..Phenomenal! If you want more amazing performances from Jenny , get her Cd “CHINOSERIE” ( if you didn’t yet …of course)…..incredible playing and beautiful music!

I do agree with you …Shostakovich( and others) exclusion was also a shame! Shostakovich suffered a kind of “double censorship” : In the Soviet union, for being “too modernist” and in America for being “old fashion” and “too tonal”..funny!! The modernist fashion that took place in the 70’s harmed Classical music in many ways ..thankfully and fairly , Shostakovich is recognized as a truly great master …in my opinion, the greatest Russian composer. My perception (i may be wrong on this) is that in places like Yale and in some music criticism circles there’s still this kind of exclusion on today’s great composers such as Einojuhani Rautavaara who writes “very tonal” music and is (in my opinion, again) a truly great master ..and living composer.

At about the same time Greg was studying in New Haven, I was studying in Cleveland, and my mentors were having me study the Britten “War Requiem” and “Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings”, not Babbitt’s “Partitions” for piano. I can’t deny Greg’s experience, but it wasn’t like that everywhere.

Readers may want to look at Joseph Straus’s book, “Twelve-Tone Music in America” , which includes a sub-chapter called “The Myth of Serial Tyranny.”

I don’t mean to say my education focused only on Britten and Shostakovich; in fact, my teachers tried to point out a “third path” (not “third stream”), that was more progressive than Shostakovich, but less hermetic than some of the high modernists. This meant Crumb and Lutoslawski were important influences; Berio and Ligeti were valued more than Boulez and Babbitt.

I think it is important to avoid simple equations like tonal=good, atonal=bad. Britten and Rochberg (in both his tonal and atonal guises) mean more to me than Shostakovich and Del Tredici.

Greg, I’m glad to hear you speak of modernist music with affection – it’s important to recognize that it is OK to love Britten AND Berio AND Davidovsky AND Rochberg. I agree, inclusion is better than exclusion.

I’ve read the Straus book, and I also was at the 2nd performance of the “Concord Quartets” while in Grad school, and let me tell you, all hell broke out in central Jersey.