I already said much of what follows, in my post about Alec Baldwin’s favorite records. But it needs saying again. It’s crucial for classical music’s future. Remember the commandment: Respect the culture we find outside classical music. So let’s take another look at what that culture is.

I was driving the other day, and listening to an NPR show about American vice-presidents, a subject it’s easy to have fun with. So when the host mentioned George Clinton — veep during Jefferson’s second term — all at once we heard music from George Clinton the funk god.

I was driving the other day, and listening to an NPR show about American vice-presidents, a subject it’s easy to have fun with. So when the host mentioned George Clinton — veep during Jefferson’s second term — all at once we heard music from George Clinton the funk god.

“No, not that George Clinton!” said the host.

And the moral of this story, for the future of classical music? NPR’s producers could assume that listeners would know the funk George Clinton, and in fact might have thought of him — I know I did — as soon as they heard the name.

Which is to say that pop music is everywhere in our culture, not just as the plague some intense classical music loyalists imagine it is, but as a common reference point, shared (let’s note) by just about everyone, includingeducated NPR listeners, whom I’d think would be a target audience for anyone trying to widen classical music’s reach.

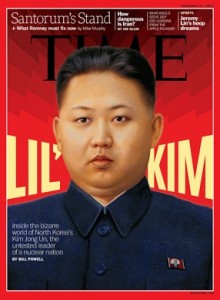

Another example: Time has a cover story about Kim Jong-eun, North Korea’s very young hereditary leader, and the words on the cover are “Lil’ Kim.” Which of course is a play on the hiphop star Lil’ Kim, the first woman to have a No. 1 pop hit with a rap song. A name Time figured its readers would know.

These pop references are everywhere. “Jailhouse Smock” as a front-page headline in the New York Daily News. Or this jokey aside in an otherwise serious New York Times piece on economics: “Weimar Germany’s inflation led to Hitler; some blame inflation in the United States in the ’70s for giving us disco.”

Or my favorite, a headline in a long-ago piece in the Times food section, about root vegetables: “10000 Maniocs.” Anyone reading the food section, the editors must have thought, would know Natalie Merchant’s band 10000 Maniacs.

WNYC, New York’s public radio station, is giving away Bruce Springsteen’s new album to people who donate money in the current pledge drive. Which means (to state the obvious) that a lot NPR listeners want to hear it. So again, NPR listeners surely are the precise demographic classical music needs to reach. And if you want to know what music they like, go to NPR’s terrific music page, on which classical music takes its place as one of many musical genres, and certainly not the main one.

All of this, for most people in our culture, is stating the obvious. But some people in classical music aren’t there yet, don’t understand how pop music — in all its great variety, with quite a bit of artistic depth — is what our culture’s music is. When I listen to public radio — Morning Edition, All Things Considered, the Brian Lehrer and Leonard Lopate shows on WNYC — almost all the theme music, the musical logos the shows us, has a beat.

Or else people think this is somehow horrible, a victory for the forces of noise and thoughtlessness. From which classical music proudly stands apart. It’s a shame that people think that. It’s so wrong, and — I’d think this is beyond dispute — will get us nowhere when we try to reach out beyond classical music’s borders.

Because who are the people who’ve fallen — allegedly — into noise and thoughtlessness? Or who, less strongly, have accepted music that’s shallower than the music we want them to like?

They’re our friends, neighbors, and family. Not to mention the editors of the New York Times, the producers at public radio, and, for that matter, the curators at the Hirschhorn Museum in Washington, where in May there’s going to be an art piece projected on the museum’s outside, accompanied by multiple versions (the original and covers) of “I Only Have Eyes for You.”

We’d better embrace the culture we’re in, enjoy our status as one of the many musical genres that give us so much diversity, and tell people not why we’re better, but why we deserve their attention even while they’re giving money to WNYC, so they’ll get the new Springsteen.

Or else we’re going to get very lonely.

Another fact some “purists” could be reminded of is how Elvis donated the money to keep the RCA classical label going. The Guarneri Quartet was indebted to Elvis for their recording career.

Totally agree. Having the idea that classical music is “better” than other types of music is being just as narrow as those who say they don’t like classical music. Right now I’m listening to a Byrd mass on Spotify. A minute ago I was rocking out to Blink-182. Before then I was listening to Common. You don’t get fans by saying, “like us because we’re so much better than that other music which really doesn’t even qualify as music.” You get fans by saying,”our music is timeless and awesome.”

I wonder what it would mean to ask Gerhard Richter or Mark Strand or William Gass to respect the equivalent of pop music in their fields. Why do we ask classical musicians to do something we wouldn’t ask of at least some practitioners in other fields? I once heard Terry Gross ask Pierre Boulez whether he likes pop music. Would she really ask Gass which airport novels he holds in esteem?

This is known as circular reasoning. You decide in advance that pop music, taken as a whole, is the equivalent of airport novels, and then rhetorically ask whether it makes sense to ask literary writers what they think of it. You’ve set the test up so only one answer is possible, but you’re also not dealing with reality. (Sorry to be blunt.) Pop music is far better than you make it out to be, and if you ask leading classical musicians what they think of it, they’ll often give you a ringing endorsement. Likewise people in the classical music business, and many classical music fans. Google Simon Rattle’s view of pop music, just for instance.

Greg, I always find your thoughts stimulating because they are different enough from mine to cause me to re-think things. This post makes we want to ask some questions. You cite “Respect the culture we find outside classical music” as a commandment. I want to ask is this mainly because that is how we can infiltrate the popular culture? Or is it mainly because respect is a basic ethical good? Can you respect something and still be critical? Can you, in other words, adopt a critical stance towards popular culture, or is that forbidden? To go further, what about a critical stance towards classical music new or old? Is it permitted to offer critical commentary on a new opera or symphony? Or to re-evaluate a composer in the ‘canon’?

Bryan,

In my experience, people fully immersed in popular culture take a critical view of it. At one point, when I gave talks on the future of classical music, I’d warn people in advance that I might not be too patient with questioners who denounced pop music. As I’d sometimes say, “If you want to say that much of the music on the pop charts is bad, congratulations. You’re a rock critic. That’s exactly what rock critics say.”

Of course we should take a critical view of everything. To respect something doesn’t mean not to find any fault with it. It means to take it seriously, and understand what its virtues are. Too many people involved with classical music talk as if popular culture is nothing much more than a cesspool. That’s radically wrong.

And if you want to know what area of discourse I most aimed my comment at, how about marketing? Can we really go out in the world to build an audience for classical music, and lead off our promotional pitch by saying, to the people we’re trying to reach, “The music you currently listen to is crap”?

Better to be lonely than to have really irritating, self-ingratiating friends like you.

Respect is certainly important and I agree that it is sometimes lacking in the classical community when it comes to pop. But I sometimes I wonder if that lack of respect is always as widespread as you make it out to be. (I could be wrong). But in my experience, nearly everybody I know who professes to like classical music, goes to the symphony, buys a few CDs etc. etc. likes other kinds of music that are not classical. Nearly every music student listens to other things as well, as we all know.

But this brings up an immediate question: Do all these different musics fall under pop? I must confess that I am not always sure how far your definition of pop culture extends, and I have been reading you for a long time. Is it more or less everything that is not classical, but has a modicum of circulation? I am assuming that it is because you seem to be talking about the entire general culture out there. For example, is easy listening (a very large demographic) included? But we do not hear much about the easy listening genre in this blog, nor is there much reference to country music (which appeals to the largest demographic in North America). Two genres that are definitely not cool among some in the pop world that I have known.

Respect can also be seen the other way. For example, I have met many people who not only do not like classical music, but have little respect for it as well. It would be interesting to see what sort of reactions would come out of that discussion in this blog. Would one get the same sort of denial that, as you point out, has been a problem with traditional classical audiences. And, within pop music, there is the problem of listeners who do not respect each others genres (which goes well beyond mere dislike). Pop culture is far from a unified world full of tolerance. We all know that because we all live in it. One finds out in a hurry how deep this can run in the average workplace when music is on that someone does not like and gets rather hostile about it. Not everybody likes, say, rap, pop, country and easy listening equally. That is why we ended up with Muzak in department stores. How does one please (or at least not offend) very different demographics in the concert hall with crossover genres like alt-classical?

One last point. Is respect really the same as embracing something? You say we “had better embrace” the culture we live in. To me the image of embracing signifies the expression of unreserved love. Must one really love everything about one’s culture? Is one even able too? “Had better” is pretty strong language, which in English is reserved for special contexts. You cannot force anyone to love something. But you can indeed ask for respect, which in any case is due to every human being.

Herbert, I wrote you a long, discursive answer. But I’m going to add this shorter one, addressed to your point about the pop music genres you say I don’t address.

If we were having this conversation about books, we’d understand that there are endless book genres — textbooks, self-help books new age spiritual books, cookbooks, computer manuals, guides to gardening, chess, and a myriad of other subjects. And much, much more. Romance novels.

But it wouldn’t occur to either of us to ask why the New York Times Book Review doesn’t review textbooks or gardening guides, or computer manuals. Or romance novels. That’s because we understand the cultural context in which the various book genres thrive, and also the context in which the Book Review is published. We know the Book Review mainly reviews literary fiction (with a little popular fiction mixed in), and serious journalistic nonfiction (with some scholarly nonfiction mixed in). And we see no need to question that.

But now we’re talking about pop music, and with all respect, I can see that you don’t understand the cultural context in which the various pop genres you mention function, and in which people in various demographic groups — particularly mine — experience pop music.

You treat these pop genres as if they ought to have equal importance, but the only people who treat them that way are a very few music business professionals — people who edit trade magazines, let’s say, who need to publish something about every genre out there.

The rest of us simply like what we like, which is very much a function of where we are in the world. I often go to a coffeehouse called Tryst, in the Adams-Morgan neighborhood in Washington, where I live. The other people there are almost all younger than me, and come from what I might describe as a smart, post-college, alternative-culture demographic. And so the music playing in Tryst speaks to that. It’s almost all indie rock. You won’t hear country music, showtunes, doowop, easy listening, R&B, or even much hiphop.

This is a musical demographic I’m very easy with. Seems like my native country, though I don’t know a lot of it. And because I’m older, I’d include people more my age, like Dylan, Springsteen, and Lucinda Williams.

The music playing in Tryst is also (very broadly speaking) the music I see reviewed in the NY Times and the Washington Post. It’s the music, by and large, that’s featured on the NPR website. It’s the music I hear on Saturday Night Live. (Again speaking very, very broadly.) It’s the music rock critics tend to like.

And why does this matter for the future of classical music? Because the people at Tryst are — as I look at them — essentially the same people I’ve seen at classical performances (especially of new music) that have succeeded in attracting a new, young audience. So this is the demographic — smart, educated young people, who make up their own mind about culture, like challenging music, and (about music) have developed taste and a sense of connoisseurship — that classical music might look to, in trying to expand its reach. I’ve seen thousands of people like this at certain classical events in New York. Or cheering classical music in other contexts.

Anyone is free to disagree with my description of this demographic and its musical taste. But that these demographic differences exist, no one can deny. And also that they’re crucial for

understanding how pop music functions. I might find it interesting to talk about country music (and, back in the early ’90s, was somewhat appalled that rock critics mostly didn’t write about Garth Brooks, the top-selling artist of that era, because his genre was country; how could it not be worth asking how country had suddenly jumped to this eminence?)

But it’s not useful to talk about country music in the context of finding a larger classical audience, because country fans, by and large, aren’t going to be in that audience. If I had to point to one musical place where the new classical audience might be found, it would be NPR’s music website, which talks about a lot of music, but certainly doesn’t treat genres as equally worth talking about. The website represents the taste of NPR listeners, and of NPR’s staff, just as the NY Times Book Review represents the book-reading taste of Times readers, and the Times’s staff.

None of which would be remotely surprising to anyone with an everyday familiarity with pop music. In fact, it wouldn’t be necessary to say this at all. Everyone understands it all instinctively. These are some of the basic facts of pop music life.

And so forgive me if I say that having to explain it all, in the most basic terms, to people in the classical music world is really quite alarming. It shows, once more, that classical music lives in a cultural space all its own, and that at least a vocal minority of people inside that space don’t have much sense of what’s going on outside it

Which then makes it harder to find a new audience for classical music, because too many people in the classical music world don’t know who that new audience is.

[Here’s the first answer I wrote:]

Respect is indeed not the same as embracing something. I should have been more careful with my wording. In fact I do think the classical music world needs to embrace popular culture, since that’s where much of today’s art is being made. And it’s what the audience we’re looking for is involved with. Respect would be the minimum we owe (in my view) to popular culture, but I think we should go beyond that. I should stress that I’m not speaking theoretically, at least in my own case, because I go back and forth between high art and popular culture every day.

Easy listening isn’t a large demographic anymore. That was some decades ago. I remember listening, with a kind of bemused wonder, to Mantovani on the radio during the 1970s, but I don’t find that sound on the radio at all anymore.

But to address your larger point, Herbert, I can’t take every subject I discuss and go back to its roots, set forth all the most basic thinking about it that’s been going on for many, many years. I have to assume at least some familiarity with the kind of discussion that, for instance, goes on about pop music genres. You’re right to say that there are all those genres out there, and that some (country, which I’ve enjoyed quite a bit) don’t get mentioned here as much as others.

But then when I was a pop music critic, and when I was music editor of Entertainment Weekly, I didn’t deal with country music all that much either. Each pop genre has its place in the world, overlapping with many others (as a rule), and which you deal with depends a lot on your own demographic, and on the demographic of the people you’re talking with. There’s a huge critical and scholarly literature about pop music, not to mention endless journalistic writing about it, and the genres I implicitly or explicitly stress in my writing here are the genres, speaking generally, that are stressed in that literature. Which is to say they’re the genres stressed by the people most involved in discourse about pop music (people, for instance, who read about it very seriously), who in turn are the pop listeners most likely also to listen to classical music.

Or let me put it more concretely. If I don’t see Chris Richards, the pop critic of the Washington Post, talking about country music very much, and if I don’t see it featured very strongly on NPR’s music website, and if I don’t see Greil Marcus — maybe the leading rock critic, and quite a distinguished intellectual — talking about it, then I feel that I may not need to, either. There are times when this is wrong-headed (when, for instance, the top-selling pop music star was Garth Brooks, a country singer), but by and large it makes sense. I’m not trying to deal with pop music in some overarching scholarly way, treating all of it as a phenomenon in our culture. I’m dealing with it as a living reality, from the point of view of my own demographic, and the demographic most likely to be in the new, young audience classical music is trying to attract.

All of which wouldn’t need to be said in a pop music context! The idea of Rolling Stone or Spin or NPR’s website explaining in this way why they deal or don’t deal with various pop genres would be laughable. Their audience already knows all of this.

As for how many people in classical music strongly reject pop music, that’s a really good question. Every study I’ve seen of cultural taste says that people today are omnivores, comfortable with both high and popular culture. One European study didn’t even include any look at people whose tastes were only for high culture, because so few people like that were found that their number wasn’t statistically significant.

And yet, in spite of this, people with this point of view keep popping up in comments on my blog. I wonder, sometimes, if I should even bother answering them, because — again, as studies show — very, very, very few people (if you look at all of our culture) think that way.

When I talk to younger people who are classical music professionals, they’re complete omnivores, and some say they don’t make any distinction between high and popular culture. They just take each sample of either one for what it is. Mahler, great music. Bjork, great music. Justin Bieber, popular fluff. Massenet, popular fluff. (That last opinion, by the way, comes from Renee Fleming, who offered it at a panel discussion at Juilliard, when she was asked to state the difference between art and entertainment. She refused to do it, and then, in perfect honestly, said that the Massenet opera she was then singing at the Met was pure entertainment fluff.)

Greg, thanks so much for taking the time to reply. I really appreciate that. Your work is extremely important, and deals with general problems that I have been trying to make sense of for a long time. When one actually meets the challenge of expanding our concert audience, I had not really thought so much in terms of, to put it in a somewhat crude way, “strategic marketing”. But I suppose other avenues of life do it so why not classical. Which would then naturally mean that the strategy you speak of (attracting the “smart crowd,” however one manages to determine that – it is a tricky notion that has been problematic within classical music as well, as we all know) would then, realistically speaking, have to be modified and tailored as one moved into other regions of the country. For example, what would work in New York or Boston might not work equally well in, say, Dallas or Fort Worth, where Van Cliburn, certainly, turned countless country fans into supporters and lovers of classical music. And further, there is probably a wider range of possibilities in a giant metropolis than in medium and (especially) smaller sized centers. In any case, I honestly do not see how the same ideas would necessarily have the desired effect on the Canadian Prairies (where I grew up). For example, in NY or London there seems to be a bigger potential audience for avant-garde/pop fusions (a notion that occasionally pops – pardon the pun – up on this blog in one way or another). But I really wonder about the efficacy of that in some of the more outlying areas of North America. In any case, the more far-flung regions all have at least some kind of orchestra and musical community which has to meet the challenge of attracting a new generation of listeners if the so-called “classical” institutions are to survive in some form. The (re)development of a choral culture, I think, always has potential. And yes, pops concerts with a classical/country theme have been known to fill halls. And there is always the impetus and inspiration of immigrants from Asia and parts of South America. Why do they have so many young people interested? I believe that it is partly because they have somehow developed a profound respect for a European tradition that is hundreds of years old. Connoisseurship of European classical music in Japan has astounding depth (and enough market attraction to maintain a vital if small niche ever since the 1930s). Japanese record labels are in a way better custodians of historic classical recordings than the major European and American record labels. In a related way, music lovers of European descent are in awe of the long traditions of classical Japanese or Indian music to the extent that we bother to inform ourselves of those areas.

I will add, to get back to the original theme of your discussion, which is respect. Along with what you are addressing, there is another issue of respect within the classical culture itself that still lingers, and that is the simple but old problem of putting the lighter and more entertaining “classical” idioms on a lower plane. Over time, that subtle or not so subtle lack of respect has had catastrophic consequences for us all. I believe that it has bearing on your general discussions here. Schumann mercilessly trashed Italian opera and Parisian salon music. As it turns out, he gravely misjudged the staying power of Rossini and the beloved bel canto tradition and now even 19th C salon music is making a huge comeback in the small world of highly dedicated classical connoisseurs. (My own shelves are full of it). In the tradition of Schumann, later generations trashed cheap transcriptions and the shallow virtuosity of showy concertos. It eventually led to an utterly crass and sweeping differentiation between art and entertainment, both within the classical world, and in terms of the classical world versus the rest of the world (the tendency to view post 1950 pop culture as garbage is merely a symptom of this). For a long time even composers like Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Puccini and Rachmaninoff were seen as more on the entertainment side, and certainly no worthy of “smart” discussion. Wagner and Schoenberg of course represented art. If a classical lover enjoyed the entertainment side, it was more as a guilty pleasure to be apologetic about. To solve the classical-pop problem of respect I think we can, and may have to, go even deeper to really get to the philosophical root of the problem within the classical world. Busoni knew there was something wrong. He spoke acidly about those he called the “apostles of the Ninth Symphony” and said that they had a much too narrow view of “depth” in music. Depth for Busoni was vastly increased by mixing in lighter genres. For him, to enjoy one’s self during carnival time was to show more depth of feeling than slinking about the streets morosely while everyone else was having a good time. Within the small world of diehard classical record connoisseurs (the kind of music lovers who buy all those thousands of Chandos, Hyperion and Naxos CDs), there is an unimaginably huge increase in the valuing of lighter genres from the 19th and early 20th centuries. I consider it a minor sea change in aesthetics. We are talking about people who love lighter genres, can discuss them intelligently, and they no longer accept being told that such tastes are beneath notice. All the young pianists at Juilliard, etc. now playing transcriptions by Horowitz, Godowsky, Cziffra, Volodos, Hough and Hamelin are but a tiny symptom of this. It may not seem like much in the larger pop world (or in your general blog – not a criticism!), but I have a hunch, after much thought, that it is of profound significance in helping the classical world get its own aesthetic house in order. Some of the “classical” attitudes you do battle against in this blog are the unconsciously product of attitudes developed over many generations and the people who express them do not necessarily know the deeper historical reasons how they really came to hold them. I do not like to come down hard on them for that reason.

I did not really mean it as a deep or fatal criticism that you had not treated genres equally. I am well aware that such is not a realistic goal for anyone and would not show a whole lot of musical discrimination (in the good sense) in any case. It was more by way of observation based on what I have seen over time. But thanks for explaining and thanks for being patient.

Thanks so much for these thoughtful comments. Very much to ponder there!

I think we need to be as imaginative and resourceful as possible. And, of course, that the resources will differ in different places.

Two thoughts, though. About the smart pop/classical overlap, yes, it’s biggest in major cities. But a Facebook friend of mine, Lia Pas, started a choral group in Saskatoon, which gets a much larger audience, Lia says, than the local chamber music series, singing mainly contemporary classical pieces. She does this by stressing pieces that are spiritual, meditative, by composers like Meredith Monk and Pauline Oliveros (which certainly isn’t easy-listening programming).

I think we can do well in smaller places with approaches like these. We’ll just have smaller crowds. It’s not the audiences don’t exist.

You have put forward good arguments Greg but I am not sure I agree with them. In the U.K. the media hotshots largely share similar views and tastes in most things, they are really a class apart. It has long been known that a New Age performer who fills a large concert hall may well not get reviewed, whereas a cool, politically savvy post punk band, that plays in a trendy bar to a handful of people, will get reviewed. Combine this with the fact that the B.B.C., press arts pages and the Arts Council largely employ the same small group of people.

In order to reach the audience you are talking about classical music is continually thwarted by the few gate keepers that run the media.

I sincerely hope the business adviser Dan Kennedy does not mind me quoting his three principles as I believe they are definitely applicable to classical music. Here they are:

Every morning, I repeat three concepts to myself:

I will do the opposite of whatever the majority does. I will run toward the fire.

I will find breakthroughs outside the majority’s approach to any given business…not inside it.

I will stay relentlessly focused on the obstacle to, and the source of all wealth: attraction of customers.

Speaking of NPR – their latest “First Listen” is the collaboration album between Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood and Krzysztof Penderecki – talk about respecting the culture. The respect goes both ways and exploring connections, as well as celebrating differences, is what makes music (not genre specific) stronger, exciting, resilient, sustainable.

Thanks for telling us about this, Libby. When I heard Greenwood’s “Popcorn Superhet Receiver” a few years ago, I thought of Penderecki. Many similarities, though Greenwood sounded entirely original to me, and if anything (for me) did texture writing better than P. Glad to know they’re working together!