No, not the surge in Iraq. This is a surge, or at least a heartening

increase, in ticket sales, which I’ve been hearing about for the past

couple of years. Of course — since, as I’ve said, we just don’t have

reliable data for classical music ticket sales and finances (I should put that in bold type) — I don’t

know how big this surge is, or how broad, by which I mean how

widespread it is in the classical music world.

We know the

Metropolitan Opera has been selling more tickets, but that might be a

special case, caused by Peter Gelb’s unique innovations. The surge I

hear about informally involves big orchestras, and while that might not

mean that smaller orchestras are selling more tickets — or that

chamber music concerts are — it’s certainly a good thing, and worth

thinking about, even if we don’t know very much about it. And while I won’t just now pore through orchestras’ annual reports and tax returns, looking for data, I’ve noticed that the Pittsburgh Symphony shows a notable increase in concert revenue from 2005 to 2007, which could be due to increased ticket sales (or might not be, if, for instance, they raised ticket prices a lot), and that the Cleveland Orchestra shows a similar but smaller increase from 2005 to 2006. (I’m using annual reports available on both orchestras’ websites.)

I’ll also note that last October, in an obscure press release announcing senior staff promotions, the New York Philharmonic mentioned something that you’d think they’d trumpet from the rooftops, that combined subscription and non-subscription ticket sales have gone up 38% over the last three years. This was in a paragraph about their marketing director, who’d been promoted to the higher rank of vice president. So there we have testimony to the surge, from one orchestra, at least. (If anyone has further documented evidence, please let me know! I’d also be happy to have private data, which I’ll keep confidential.)

So assuming that this surge is real, what does it mean? My working assumption — thinking especially of what I know about orchestras — might go like this. Having seen that their ticket sales were falling, many institutions upped their marketing, using solid, well-established, traditional techniques, based on solid research. That’s the first thing anyone should do, faced with falling ticket sales. Of course I think more radical changes will be needed in the long run, but the first thing to try is the traditional approach. It might work better than you think, which is another way of saying that your marketing right now might not be all it could be.

But then we have to ask if institutions are selling more tickets to their established customers, or whether they’re selling to new people. The first seems likely, if only because it’s where — in your heightened marketing — you’d want to start. Get a database of people who used to buy tickets, but aren’t buying now, or who are buying fewer tickets than they used to. Do some research — questionnaires, phone surveys, focus groups, individual interviews — and find out why. Then address those problems, and above all target marketing directly to these people. If you do this well, you’ll get results.

So then — I’m theorizing, I should stress — we might have something like the following. Ticket sales were falling. Hard-core ticket buyers now are truly hard-core. They’re your most loyal audience, the people whom nothing short of death can keep away. You’re left with them, I’d further theorize, because (perhaps not meaning to) you’ve neglected those who lie outside the inner circle. So now you pay attention to them again, and you bring them back.

But now you’d have another question. How large is your welcome recent sales increase? Does it wipe out the longer-term decline you’re remedying? Or is it just an uptick whose meaning isn’t clear yet, which might turn out to only be a bump in what will soon turn out to be continuing decline?

That might be the case, if — as I’ve theorized before — the decline is due to cultural changes that you haven’t addressed. That is, you’ve mobilized your marketing, and brought back people who share the old classical music culture that your institution is part of. You sell more tickets. But the number of those people is, over many years, steadily declining. So your current rise in ticket sales can’t be sustained. In not too long, your sales will fall again.

This is why you’d like to bring in new people — and ideally younger people. That’s the only way — if my theories are correct — that the decline can be reversed.

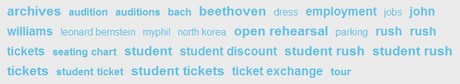

And here the Philharmonic presents an interesting, maybe hopeful picture. Go to the search page of their website. It’s nicely up to date, featuring a “tag cloud” of searches people made, with the largest words showing the most popular searches. Here it is:

Some of the most popular searches are for student tickets! Most likely, then, the Philharmonic is selling many student tickets. I don’t know, of course, how many “many” is, but let’s suppose it’s more than they sold in earlier years. Does this mean they’ve found a younger audience?

Some of the most popular searches are for student tickets! Most likely, then, the Philharmonic is selling many student tickets. I don’t know, of course, how many “many” is, but let’s suppose it’s more than they sold in earlier years. Does this mean they’ve found a younger audience?

Yes and no (as I go on theorizing). Yes, because they have some younger people coming. And no, because I’d guess they don’t and couldn’t know if these student ticket buyers will keep coming. Younger people now are open to many forms of music, classical among them. They’re open-minded, curious. Prime targets for Philharmonic marketing (if their offered low-priced tickets).

But that doesn’t mean that they’ll come back. Or, more to the point, it doesn’t mean that they’ll come back very often. And the ticket sales that orchestras depend on are repeat ticket sales, even though subscription numbers have been falling now for many years. A reasonably large proportion of the audience still subscribes, and if a future audience doesn’t subscribe, or subscribes in lower numbers, then orchestras — despite the recent bump in sales, and even if we think they’ve found a younger audience — will shrink.

Theorizing still, I’d say the burden of proof lies on those who think that ticket sales can be as high in the future as they are now. Maybe college students who try out a Philharmonic concert will become subscribers, but given the culture that younger people have, I’d say it isn’t likely. They may enjoy the orchestra, but they identify with other kinds of music, unlike the core audience today, which might like other kinds of music, but most closely bonds with classical. Maybe that will change, as the student audience (whose numbers, let’s remember, we don’t even know) grows up. But I don’t think it’s likely. If I’m right, the surge won’t be sustained, and in the longer run, mainstream classical music institutions will be forced to cut back.

When I was at the Baltimore Symphony, we began a major surge in attendance. As I mentioned elsewhere this was due primarily to a freeze in ticket prices, and a cut in some. This surge accelerated after I left, due to a generous gift from a large bank which subsidized a massive cut in prices.

I also should report, in line with your observations about New York, that the fastest-growing demographic in Baltimore was students. We offered $10 ‘rush’ tickets (available only in the last hour before curtain, so they were basically unsold) and also sponsored a party in the lounge afterward with snacks, hosted by our younger staff members.

While I was excited to see these increases (and those at the Met as well), I don’t think they’re sustainable. Our analysis indicated that you could sell lots of seats at $20-25, and that the median age would come down. But the cost per seat of a symphony orchestra concert was over $75! (The math is easy: the total budget of the Baltimore SO was about $27 million, divided by about 150 concerts, and the hall maximum attendance is 2400; that’s assuming that the concerts all sell out). So the only way to make it work is to get large subsidies.

Enter here the spectre of irrelevance. I love your baseball analogy; I used to make the same case in Baltimore. The generation coming to power (whether that means politically, or wealth-wise) that can make the subsidies happen are not fans of classical music. Or, even if they are, they realize that public or philanthropic spending on classical music benefits a small segment of the population, which should be able to afford to fund their own entertainment. Baseball appeals to everyone; that’s why municipalities line up to subsidize new stadiums.

One highly placed politician in Maryland told me (when I came hat in hand asking for more money) that he had to choose that day between closing a fire station in a depressed neighborhood or installing metal detectors in 50 schools. ‘You want me to divert that money to pay for a symphony orchestra program?’ he asked me incredulously.

The root of the problem is, as you have suggested, massive cultural change. You need look no further than my own kids: educated at top boarding schools, going on to elite colleges, with a father who works in classical music. Yet they groan when I suggest going to a concert. They’re articulate about why they groan: they can’t sit for 60 minutes at a time, without a drink, without taking a break, without texting, talking, etc. You’d think they’d want a break from multi-tasking, but they don’t.

I am also a lover of jazz, and my kids love to go to jazz clubs with me. There are some lessons to be learned here. Smaller venues enable them to get close to the performers and feel the intensity (come to think of it, they loved chamber music in the Wigmore Hall too). If a slow song comes on, and they’re not into it, they can go get a Coke, or go to the bathroom. They can text their friends, or even upload a picture or video and share it on Facebook. They can talk too, quietly, or tap their feet, squirm around in their chairs, write notes to each other….all the things that kids (and young adults) do.

But adopting the jazz model would be difficult/impossible unless the classical music world as we know it crashes. The musicians (and the ‘administrators’ too) make a small fraction of what orchestral musicians make. And to say that most of the musicians I know would bristle at the suggestion that people could text or talk during their performance(0r that it should be amplified to counter this) would be an understatement.

Why has their been so little experimentation in this area? Several of the ‘jazz model’ features are used by the Boston Pops (table service, drinks, snacks etc). Why don’t more do this? I once proposed that we build a ‘skybox’ at the symphony (‘baseball model’) to see if we could get a big corporate donor to pay for it; I found no supporters.

For now, I’ve taken refuge in the recorded music market. This (and video) is one area orchestras should excel in, and many are getting back into the game with their own labels. The cost of recording has reached almost nil, and the musicians have shown incredible flexibility in how they are paid. While I see this as an interesting and vital area, I don’t want to see live performance disappear.