I’ve enjoyed the comments on my post about ornamentation and rubato in past centuries. And I certainly agree with a point at least one commenter made, that when musicians (in the old days or now) change what the composer wrote, they can do it well or badly. But that, at least to me, doesn’t reflect badly on ornamentation as a practice. We judge all kinds of things about performances, and this just adds another element. If we flag it as especially troublesome — as if it’s worse to change the composer’s written notes in a bad way than it would be to play at the wrong tempo, or in the wrong mood — I think that’s only because we’re not used to changing the notes. Musicians in past centuries might not have felt that way.

I know some criticisms that were made of ornaments in past centuries. In the baroque era, singers were damned for inventing ornaments that made parallel fifths with the bass, a violation of the rules of harmony. In 18th century Germany, orchestra violinists were attacked for ornamenting their parts individually — each violinist (if we can believe this) adding his own ornaments to the written melody, without any coordination with the ornaments added by everybody else.

And Manuel Garcia, Jr., in his famous 19th century book on singing, offers two sets of ornaments for the opening tenor aria in The Barber of Seville, and says that one set is bad. Not for musical reasons, though — he says the bad ornaments are theatrically inappropriate, because they’re too languid for the character. (I assume the good ornaments are those used by Garcia’s father, who created the role.)

Many of you also talked in the comments about ornamenting Brahms, which I said just wouldn’t work. I guess I should clarify that I didn’t mean nobody could improvise on a Brahms piece. And in fact pianists in Brahms’s time routinely improvised in performances, inventing preludes to pieces they were going to play, and transitions between one piece and another. The practice survived into the 20 century, and there are recorded examples, including one from as late as 1969, played by Wilhelm Backhaus at his last recital.

What wouldn’t work, I think — or wouldn’t work most of the time — would be to play a Brahms piece, and change the melodies Brahms wrote, the way any 19th century singer would have changed the melody in a Rossini aria. Suppose, for instance, that some orchestra’s principal horn player adds something of his own to the first bars of the second symphony, playing the top line below, instead of the bottom line, which is what’s in the score:

That would be terrible, ecause the three-note figure in the third measure — the one that’s changed — is a key motif all through the first movement. Just before the passage I’ve quoted, it showed up inverted, in the cellos and basses. (Or, more likely, form the motif takes in the cellos and basses is the ur-version, and the horn plays the inversion.) During the 19th century, music — at least from classicist composers like Brahms, and avant-gardists like Wagner — began to suffuse itself with motifs. If you change them, you audibly spoil the coherence of the piece.

But back to Rossini, which is where this discussion started. In my post, I talked about how he started to write out the ornaments — or some of them, anyway — that he wanted singers to sing. We should understand that this is deceptive, first because not all the ornaments are written out, and secondly because singers would change the ones that Rossini wrote (and often have to, because passages are repeated, and nobody would sing repetitions without changing them).

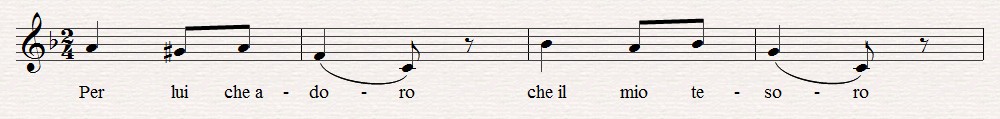

And Rossini’s scores are deceptive thirdly because his earlier operas — which in places look pretty bare — have to be ornamented just as fully as the pieces that bristle with ornaments. This goes against our present grain. We’ve all been taught to play what’s in the printed score, and now we have to learn that this passage, from L’Italiana in Algeri, an early work, with ornaments mostly not written out

would very likely be sung with as many ornaments as this one, from Semiramide, one of Rossini’s later scores, where he did write out suggested ornaments:

I tried improvising ornaments myself one afternoon, walking down the street in New York and singing one of my favorite moments in L’Italiana, making up changes for it. (It comes later in the aria whose beginning I quoted earlier, “Per lui che adoro.”) But I found that some of the wilder rubato variants that singers of the time might try — like the one I quoted in my earlier post — are hard for me to improvise, because I’m a classical musician, and I have trouble keeping the beat in my head while I make up melodies that phrase across beats and barlines, as jazz musicians know how to do.

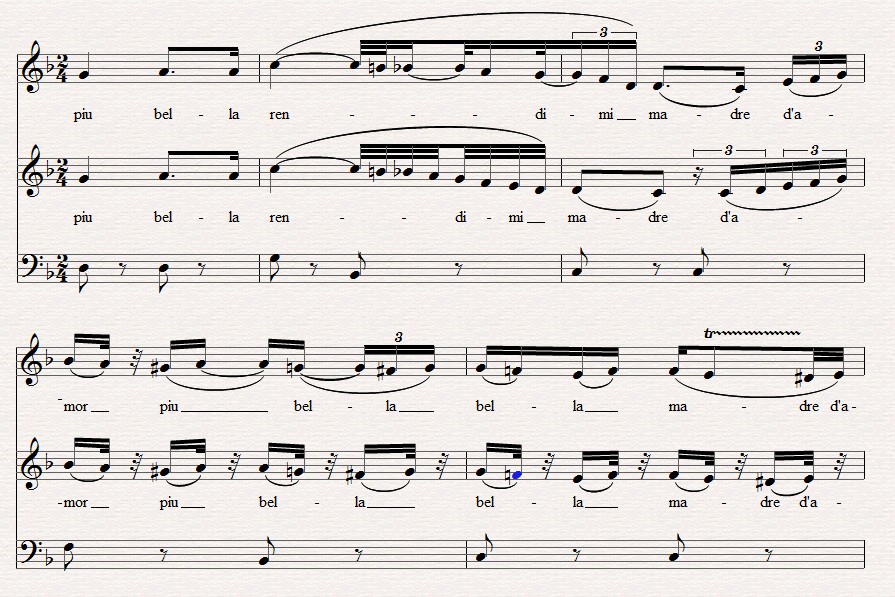

I came up with simpler variants, which were nice enough. But that night I got out my notation software, and started having fun. Here’s what I came up with. What Rossini put in his score is in the bottom staff, and my variant is on top of it. I added the bass, so you can see how my ornaments stretch across the measured pace of the harmony:

I really like my version. The original — which I used to think was wonderfully elegant — now seems bland to me.

And what I wrote is theatrically appropriate. The character singing the aria is a smart and beautiful woman who’s dressing and putting on makeup, knowing full well that the silly man who loves her is watching. She’s playing a trick on him, and nothing could be more appropriate than to put makeup on the aria as well, making it less innocent and more seductive, to exactly match the singer’s acting.

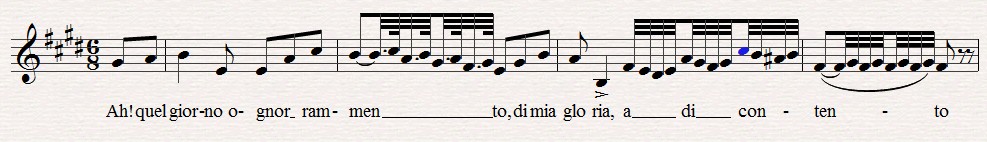

As a footnote, here are some elegant ornaments for a passage in “Oh bella a me ritorno,” the cabaletta to “Casta Diva,” the great soprano aria from Bellini’s Norma, as sung by Giuditta Pasta, the singer who created the role. Again they’re from Manuel Garcia’s book. The bottom line, as usual, is what’s written in the score, and the top line is what Pasta sang. Just look at those quintuplets, a rhythm never (or, outside Chopin, virtually never) found in written music of this period. And look also at the lovely rubato in the final measure. Pasta, we should remember, was considered one of the great artists of her time, certainly the greatest of the bel canto era sopranos. This is how she made this passage her own (I left out the words because I don’t have the Garcia book with me, and can’t recall exactly where Pasta put them):

The enemy is the recording.

Take those early music performers who’ve revived and become conversant and comfortable with the idea of extemporised ornamentation (whether truly on the spot or prepared or a bit of both*): what exactly do they commit to a recording that can be played over and over again.

And why does that “immortalisation” of a moment in time bother classical musicians in a way it doesn’t seem to bother jazz musicians. Or does it? How do jazz musicians feel about what is at heart an extemporised art being captured for all eternity on a recording?

*We know from contemporary sources that even in the 18th century there was an assumption that some musicians at least some of the time would “prepare” their extemporisations (as you’ve been doing Greg) and with it is the implied acknowledgement that the “extemporisation” would be all the better for the preparation. So in a sense all this ornamentation and variation was a game in which composer, performer and listener were complicit.

Early singers were trained in creating poetry in Latin,Greek and Italian. They also had to learn how to improvise extemporaneously, and they were drilled and tested on all these subjects, plus harmony and composition.

At one point there were four kinds of trills they had to learn. We still no what they are but taste has changed since the days of Farinelli.

According to Jean Baptiste Faure in “La Voix et le Chant”, Paris, 1886, and in English, 2007, NY Vox Mentor, Rossini, by writing out his ornaments, killed off the old style (bel canto), becasue singers no longer had to study to become composers, and they got lazy!

More entertaining and informative insight, Greg–thanks again. I think Yvonne’s comment is interesting, especially in regards to the “immortalisation” of a moment she refers to.

It’s a pretty common thought that improvisation can best be defined as spontaneous composition. Jazz improvising, in that regard, is simply using the vocabulary you’ve developed to create something meaningful on the spot. It’s the difference between reading a speech and speaking extemporaneously. I don’t think a jazz musician would be that upset at an improvisation being forever immortalized, since it is merely a representation of his or her composition on that given night, and it likely is reflective of that musician’s control of jazz vocabulary. Consider the myriad alternate takes that never made it on to original albums. On of my favorites is Freddie Hubbard’s “Hub Tones.” The alternate take of “You’re my Everything” contains solos all around that are good, but not as good as the ones on the main take. Freddie wanted to put his and his bandmates’ best foot forward in the presentation of their spontaneous compositions.

I would, in the interest of curiosity, reverse the question: do classical musicians really fear their improvisations being recorded? And to add to that (although this may be another very different topic), can we as listeners really “trust” a recording–improvised or not–anymore with the level of editing that is currently possible, even for live recordings?

I hope you’ll have mercy on my Mozart sonata cycle–for I’ve added what I hope will reflect spontaneous Mozartean embellishments in the repeat sections–true, they can be played over and over again, but the idea is to provide a snapshot of a performance as if it would be ‘live’ and ‘in the moment’.

There are a few things at YouTube, and in 1997, I recorded a simulcast cybercast–that first internet recital–was out on cd, but now at http://www.rhapsody.com; Cui Preludes are on Naxos; Leroy Anderson Concerto on Naxos; Schifrin 2nd Concerto on Aleph; and the Vivaldi disc will be on Naxos in June, and the first three Mozart sonata cds on Koch in July. If you email your address to me, I will send the Anderson to you and then the Vivaldi and Mozart next summer. The YouTube is, for now, the sampler if you like Chopin Etudes, Schulz-Evler Blue Danube and video of Prokofiev 3-

Thanks for the immunity on the Mozart!!

Yvonne makes a great point about “somewhat prepared” extemporisations. Absolutely. Whether you are realizing figured bass or embellishing a composed melody, you need a high-level knowledge of harmony, stylistic conventions, etc. Improvising embellishments, a performer is creating, in essence, a variation of the melody, and needs to know not just the melody but it’s harmonic and structural context.

Yvonne’s point goes well with Chris’s comment, “Jazz improvising . . . is simply using the vocabulary you’ve developed to create something meaningful on the spot. It’s the difference between reading a speech and speaking extemporaneously.”

To do improvised ornamentation well, whether in classical, jazz, Indian, or any other music, you have to have developed a wide and deep enough vocabulary to fluently vary the written text in a meaningful way. And that takes years of study and practice, including tremendous amounts of avid listening and formal and/or informal coaching by more experienced mentors to reach a level where it’s fair to ask an audience to pay money to hear you do it.

Most of the proficient early-music performers who have reached this level of proficiency, at least those I know personally, aren’t adverse to having their performances recorded. Those who are new at it, still experimenting with it, whether young or old, often don’t want those experiments shared, especially with posterity.

This combines with the shrinking of the CD market. In the comments on another post, Lindemann mentioned Jason Moran’s improv on the Brahms Intermezzo, Op. 118, No. 2. It’s on a Blue Note CD, recorded in late 2002 at the Village Vanguard; released in 2003, it’s already out of print and not available on ITunes or as an Amazon.com download. I bought a used copy through Amazon because I wanted to hear it.

Getting anything commercially recorded is next-to-impossible now, and whatever level of a conglomerate makes a decision doesn’t seem inclined at present to record those classical musicians who improvise or to keep them in print. I mentioned in another thread the Levin/Hogwood recording of the Beethoven Choral Fantasy with improvised alternate piano cadenzas; it’s out of print as well, as are so many classical recordings, including a huge number released by RCA in the 1990s.

It’s a joy to have three different CD sets of the Corelli violin sonatas by early-music performers and listen to the vastly different realizations and embellishments. (I wonder how many are still in print?) But someone buying one CD set or, even more so, downloading a recording, isn’t going to know what’s composed and what’s added by the performers without a score, good liner notes (absent in a download) that they actually read, or multiple recordings to compare.

And Chris’s question about trusting live recordings, which I take to mean as a document of a single live performance–there’s no way to trust it, unless there’s a printed assurance that the recording is unedited. Even the Jason Moran album I mentioned is a combination of the shows from two nights, and it’s not clear if portions of individual numbers have been edited together or it’s just the best versions of each tune.

There are probably more jazz musicians than classical musicians comfortable with having performances with improvised elements recorded and made public. The main reason, I imagine, is that there are more jazz musicians comfortable with and confident in their improvising. And even jazz musicians are highly selective about what they release.

My experience with early music performers suggests that for many the fact of a recording does change their approach.

For example, some who might normally be quite “wild” and flamboyant (and successfully so, given much experience, practice and skilful good taste) can be observed to significantly tone down their extemporisations and bring them closer to the unadorned score when they’re conscious that the performance will be available for repeated listening. Whether that’s concern on their own part or a kind of respect for the listener I’m not sure! Perhaps a mix.