I took a long trip over Labor Day, to attend anniversary celebrations for a marvelous art project my wife’s stepfather has funded for the past 40 years. And while I was there, I made my debut as a free improviser, either on piano (when one was available), or else with anything that might make sound — chairs I could drag along a concrete floor, my voice, resonant steel stairs I could stamp on — when we improvised inside a sculpture as large as a house (larger than many houses) that my stepfather-in-law commissioned on the land near his home.

All this was very informal. But I was working with experienced musicians, from Boston and Germany, both of them partners of artists at the celebration. So the musical circumstances were highly professional, though also quirky. I was right at home. Certainly I’ve been hearing free improvisation (and sometimes reviewing it) for more than 30 years. But what surprised me was how authoritative I felt. I’m not saying I sounded authoritative; that’s for others to judge. But I felt as if I’d been doing this all my life, which really wowed me, since I haven’t performed in public for maybe 20 years (I used to sing opera, conduct, and sometimes play keyboards), and especially since I’ve never felt this comfortable at the piano. I blanch whenever I want to play some musical example for the classes I teach.

Now, for whatever reason, everything feels changed, and I want to do lots more of this. As I don’t have to tell some of the regular readers here (Eric Barnhill, Eric Edberg, to name two), there’s a great freedom in improvisation, when you hit a groove, and the ideas just come to you. When I felt self-conscious, or cut off from the other musicians, I’d remember a Pauline Oliveros piece I heard at Lincoln Center a few weeks ago (and wrote about for the Wall Street Journal). She has the audience performing; you take a breath and then sing a sound to match what someone else is singing. Then you take another breath, and make a sound of your own. I could do that just as well on the piano, and it helped focus me on the others, as well as on myself. One marvelous moment, that happened each time we played — when you know you’re at the end, and you also know (with no doubt at all) that the others know it, too.

A wonderful thing: Nonmusicians can do this. When we improvised inside the sculpture, the artists joined their partners, making whatever sounds they felt like, including whistling and tongue clicks, which brought alive some very quiet moments. We wondered if we’d disturbed a colony of bats. My wife came in after we’d started, and told me later that she could hear the whole sculpture vibrating, from outside it.

*

On the plane coming home, I took out my iPod, and started listening to Stockhausen’s Mantra, a richly detailed piece for two pianos, with some added percussion, and also with electronic transformation of some of the piano sounds, so you think you’re hearing some electronic version of John Cage’s prepared piano. Or two prepared pianos. This is intricate music, which I’m learning very slowly, going back over the first few tracks many times, to make sure I’ve absorbed it all. It’s not that the events are tricky to grasp; they’re pretty simple, in some ways (lots of repeated notes). But there are so many of them! And so richly varied, so many harmonies (for instance) passing under and around a repeated minor third in the introductory first section of the piece.

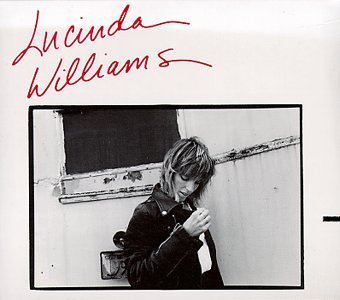

On the plane, though, it all seemed abstract, cold, uninteresting. So I listened to Lucinda Williams. I have all her albums on my iPod, except the eponymous one, her long-ago breakthrough, which — and can you believe it, for someone so important? — is out of print, available only for huge prices used. (Somewhere I might still have my LP copy, in a box in my basement. My LPs went through a fire, but I wish I’d kept better track of them.)

She grabbed me right away, from the first catch in her voice in “Right in Time,” from Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (“You left your mark on me/It’s permanent, a tattoo”). This was what I wanted; something for my heart. “Lake Charles,” from the same album, apparently about someone who died, though death is never spoken out loud; she keeps naming places the man lived or liked, or music they heard, as if those nameable remembered wisps were all she had to hang on to. Or “Ventura,” from World Without Tears, where she wants “to get swallowed up in an ocean of love,” and evokes that ocean with a single chord progression, four chords, repeating all through the song, over which she somehow creates both a verse and the kind of soaring chorus that normally gets its impetus from new chords. That’s harder, compositionally (just try it), than writing a fugue.

I listened to her for more than hour, as happy as I’ve ever been on a plane. And then she wore me out. It was too much. Back to Stockhausen. Now Mantra was everything I wanted — abstract, absorbing, detached. I was happy again. And that’s how it is, at least for me, with classical music and pop. They do different things (and not only the things I’ve described; pop can be detached, classical music can set me on fire). I could never say which was better. “Better for what?” I’d have to ask. I need them both in my life.

*

Note to Seth Rosenbloom: I’m going to post and reply to the passionate comment you posted. It’s too long simply to stand as a comment; it needs a blog post of its own, especially since it raises so many crucial issues. Forgive me for not acknowledging it sooner.

Improvisation has always been a difficult art for me, personally, since I have always been a re-creator at the piano. However, I am now finding that in playing the classics, there is a non-student feeling that comes upon me which renders me nearly in an improvisatory sense, which I like at my age now.

I wish I was there to hear the sculpture vibrate–there have been occasions in certain situations when I was able to hear building sounds from the vibrations of the orchestra–although, one time, it wasn’t just the tympani playing so well–simultaneously, it was indeed a mild earthquake at the very same time. I knew it was simply too good to be true that the tympanist was able to get such a dynamic sensaround sound.

Flying in airplanes, depending on the furation of the flight, wields the time to either read, listen to music, and for me, occasionally writing music or short stories. It’s a quiet time, that which is without emails, telephones, etc. We can focus on things we don’t typically have the time and space for. Perhaps record companies can come out with cds titled, ‘Flights of Fancy’–various compilations of works that make flying time easiest!

Thank you, Greg, for an interesting and thoughtful entry.

I cam to classical music after a love of jazz for many years and I do miss improvisation. It does seem odd that composers who try to use jazz themes in classical music they still want to put all the notes on paper. Or are there exceptions?

I use my iPod mostly at the gym and on long flights. I haven’t found Stockhausen suitable for either. For him I need to be at home, preferably with headphones to aid concentration.

Re: Lucinda…I happened to see her perform last December at UCLA with her father, a wonderful and well-known poet named Miller Williams. He would read a poem, she would play a song, and so on, back and forth. But her songs were so powerful that soon she had him reading two poems per song, and even that wasn’t enough…after “Lake Charles,” with its heartbreaking chorus (“Did an angel whisper in your ear/hold you close and take away your fear/in those long last moments”) he admitted as much. She wore him out too!

congratulations to you! you must be a one full of ambition, and also a one who would work hard to achieve it. by the way, i think the two words: niceful and excitingful should be altered to “nice and exciting”