That was on the Metropolitan Opera’s website, less than half an hour before opening night. They’d been running this countdown for days, and I loved it. How to create excitement! Or, rather, one way to do it, along with the free open house they’d had the day before; the announcement of the deal putting the Met on its own full-time channel on Sirius satellite radio. And, of course, the announcement of the video screens in Times Square and Lincoln Center Plaza, allowing anyone to see the opening night performance free.

Here’s an institution that knows what it’s doing, and especially knows that it needs a new relationship with the city it’s part of. I was at the opening performance (I live barely 10 minutes from Lincoln Center by cab, on a good day even less, and so I really could grab that countdown from the website, and then head off to the performance). And it was a triumph. The buzz was tangible, in part because there were celebrities around. My wife and I saw Sean Connery, which almost (though not quite) trumped the opera. I don’t mean to gush, but it was fun having stars around. Don’t think that some of the most serious music critics you might read didn’t enjoy it just as much as I did. And don’t think that the excitement doesn’t matter backstage. I ran into people from the Met’s orchestra, slipping into the house at intermission to look at the crowd. You think this isn’t good for the Met? And good for opera? You’d rather have an audience of musicologists, studying their scores?

And the performance was really good. You can quarrel with the singing (a Butterfly who could act the role, but pushed her voice, and still couldn’t make an impression at big moments like “Un bel di“; an apparently nervous tenor pushing his voice though he had no need to). But the new Anthony Minghella production (well, new to the Met) was both gorgeous and powerful. It was real theater, something you could take serious people to, who don’t usually like opera. There was lots of talk about the puppet that enacted Butterfly’s child. Yes, it was heart-wrenchingly grotesque, but at the same time it was heart-wrenchingly realistic, moving and yearning much like a real child (and more than a stage child ever could).

And its grotesque look, to me, at least, was part of the point. In many ways this production tore through the sometimes sentimental surface of the opera, and showed the ugly underside of the story, though without making any great fuss about that. Here’s another example. Far above the stage, on the lofty ceiling of the stage space, were mirrors, reflecting the scene below — but at an angle, so it looked uneasy and sometimes harsh. This paid off wonderfully in the last act, during the scene were Sharpless and Kate Pinkerton tell Suzuki the horrible truth. Butterfly is asleep offstage, but in this production, she was just behind some of the sliding screens that served as the house’s walls, and in the reflections above, you could see her sleeping, chillingly present in the production even though she had nothing to do onstage. Later, when she woke up, we could see that, and see her coming toward the door that would bring her onstage to her doom.

Many of the reviews I read were dubious — some of the critics found the production too modern, too abstract, not emotional enough. This, I think, means that music critics are in a cultural place that isn’t where many other cultured people are today. To anyone who goes to the theater, I don’t think this production would have seemed at all off-putting or even remarkable, except for its quality. I think of the Medea that was on Broadway a few seasons ago, or the fascinating Sweeney Todd with the actors playing all the musical instruments. Both were at least as abstract as this Butterfly, and nobody seemed to mind. So the question then becomes: Should the Met please the critics (and the more conservative part of its established audience), or should it do things that bring it into the wider world, full of people who aren’t yet going to the opera? Surely it needs to do some of both, but in the long run, the new people are more important. The old audience has been shrinking; without a new audience, there won’t be any Met. And if, to your hoped-for new audience, you look stodgy and inartistic, you’re in big trouble.

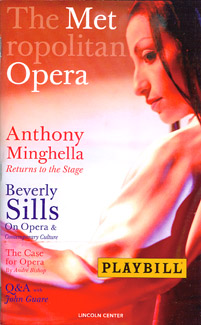

One last thing. The Met has revamped its program book:

Note that it now looks like a real magazine, complete with striking cover image, and what the trade calls “cover lines,” text that tells you what you’re going to find inside. I’ve been agitating for something like this for years. Program books should look like the kind of magazines people read in the outside world. Or at least they should if we want people to read them. I’m not going to say that nobody has moved in that direction. The New York Philharmonic program book, for instance, has a nicely spacious design, with lots of white space, and smart use of sidebars and other special text.

But the Met’s cover takes things to the next level. I’m not going to pretend that everything is terrific inside the book; the Philharmonic’s inside layout is often better, and in the Met’s book (or at least in this first edition this season) there are blocks of text in what I’m not alone in thinking is too small a typeface.

There’s also an unfortunate photo of Peter Gelb, one that manages an improbable trick — making it hard even to imagine what he really looks like, while at the same time making him look older than he really is.

These things, though, should be easy to fix. And what’s most important about the program book is its content. A lot of it addresses the Met’s central problem, which is also the central problem for classical music. I can’t do better than quote Peter Gelb’s introductory essay, written in a wonderfully informal but also very direct style. These words are highlighted in a pullquote: “My greatest challenge is to keep the Met — and opera, more broadly — connected to contemporary society.”

And that, in many ways, is the theme of the program book.

There’s an interview with Beverly Sills, titled “The Opera Singer as Pop Star,” with a teaser saying that Sills is going to talk about “the changing place of opera in contemporary culture.” Which she does, sometimes in pretty strong language. Best of all might be an essay by Andre Bishop, “The Case for Opera,” bearing this teaser: “Does the art form have a relevant place in contemporary culture?”

Bishop is the artistic director of the Lincoln Center Theater, and will be working with the Met on developing new works. And while his ideas about opera’s relevance are worth thinking about, his most provocative thought is about new operas:

And we must break away from what I call 19th-Century Thinking: not every good play or novel should be adapted for the musical stage. Most of them should be left alone. My favorite new operas (works like Adams’s Nixon in China and Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles) have been totally original; my least favorites have simply taken an old book or play and set it to music, to no real purpose beyond a stab at respectability.

Can you believe that? Serious artistic discussion in a classical music program book — and serious discussion that takes strong issue with the Met’s own most recent commissions, John Harbison’sThe Great Gatsby and Tobias Picker’s An American Tragedy (not to mention William Bolcom’s A View from the Bridge, which the Chicago Lyric Opera premiered, but which the Met also staged). If we’re going to have talk like that right out in the open, the Met could be a very interesting place.