Magazine publishers were excited when Apple introduced the iPad. There were all sorts of plans for i-publishing ventures – a new generation of digital magazines that would look better than the web and were more portable than laptops. Then the iPad launched and publishers were screwed. Sure you could sell a digital copy of a magazine. But there was no option to buy subscriptions.

Single-copy sales on newsstands are not what drives magazine revenues, and it quickly became clear that single i-copies wouldn’t do it for the tablet world either. Wired went from selling 100,000 copies of its first iPad edition to 30,000 in just a few months.

So Apple has now launched a subscription scheme. While publishers can set their own prices and terms, Apple takes 30 percent. Publishers can sell their own subscriptions elsewhere, but Apple won’t let them sell subs for less than what they cost in the  iTunes store. And customers going through iTunes will be able to decide how much of their demographic data is shared with publishers.

The problems with this deal have been much discussed elsewhere. Apple’s 30 percent is excessive. Dictating price to publishers selling outside the Apple store puts a lot of control in Apple’s hands. And no publisher wants to give up control of subscriber info, which, in some ways, is the most valuable asset publishers have.

Apple’s overreach may or may not work. iTunes has a huge lead in selling digital products. But Google has jumped in with a subscription plan that offers a more favorable deal, and others will follow.

There’s a larger issue.

One of the reasons the internet “works” is because “everything” speaks to one another and is accessible. Our browsers go almost anywhere. But with everything accessible, it’s been difficult to charge for content; so much choice means that people have alternatives to paid content. This has upended traditional publishing business models.

Apple’s app market suggests this problem can be solved. Apps don’t talk universally. They offer content or services that can’t generally be accessed from the outside. They often only work on proprietary devices. Publishers can charge not only for the app, but also for the content, and the iTunes app store experience suggests that consumers will pay.

More and more pieces of what would formerly have been on the net are now finding refuge behind these walled gardens. Facebook, for example, while it’s great for pulling in links and content from the outside, is not much accessible from the outside, and Facebook controls privacy and dictates rules of interaction and who owns your content. Twitter can be displayed on the net, but it too decides rules of the road. Last week, for example, Twitter shut out the UberTwitter and Twidroyd applications after supposed policy violations. Apple regularly declines to allow apps it doesn’t like into its app store. And the iPad, as marvelous as it is, is frustrating as hell when you try to get content in or out if Apple hasn’t approved it.

Digital rights management (DRM) was an attempt to control distribution of content, but it irritates consumers, and many resist. Somehow, though, apps (which are even more restrictive in how they allow sharing) seem to be more acceptable with users.

As we become more digitally mobile, more and more content is being moved behind app walls, and mobile carriers are fighting to control content. In the recent net neutrality battles, some of the big providers were willing to concede neutrality for the traditional web as they pushed to be able to control the flow of data on mobile networks. If the future is mobile (and it is), then there’s a lot of power (and money) to be made on who decides what gets delivered and how.

The online world, which has been an untamed, Wild West in which anyone with access could play, may be evolving into an app-driven model with walls everywhere you turn. This more closely resembles the physical world in which access is controlled by those with the power and resources to pay for it.

One of the great things about the internet was that it democratized access to ideas and information, simply because it spoke a common language. But on such an internet where content moves freely, charging for content is more problematic.

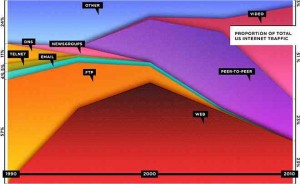

Digital subscriptions are seductive for publishers looking to be more profitable. Apps might be attractive to consumers wanting higher quality products and experiences. But apps – and the app stores that regulate the transactions and offerings – are beginning to change the nature of digital content and who can produce, distribute and see it. Maybe this was inevitable. A Wired cover story last August declared that the web is dead. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, just a different thing. But we ought to spend a little time thinking about what that next thing looks like.

[…] McLennan, D 2011, “The walled garden problemâ€, viewed 1 May 2013, http://www.artsjournal.com/rwx/2011/03/the-walled-garden-problem/ […]