Rembrandt: Painter as Printmaker, which opened Sept. 16 at the Denver Art Museum, showcases the known glories of his work—but with an eye-opening twist. It displays Rembrandt a master market manipulator, as well as a great artist.

We know, but rarely acknowledge in exhibitions, that many great artists were good at business too. Certainly, Renoir and Martin Johnson Heade, to name two on opposite sides of the Atlantic and in different time periods, churned out paintings they knew they could sell, often to tourists. So, for that matter, did Canaletto.

And Rembrandt, we know, painted some of those self-portraits as “calling cards” to demonstrate his skills in that genre to prospective portrait commissioners.

The exhibition in Denver goes deeper. With its display of nearly 110 prints, 17 drawings and five paintings–spanning his biblical, portrait, allegory, still life, landscape and genre subjects–curators Timothy Standring and Jaco Rutgers set out to show how Rembrandt manipulated the market for his prints.

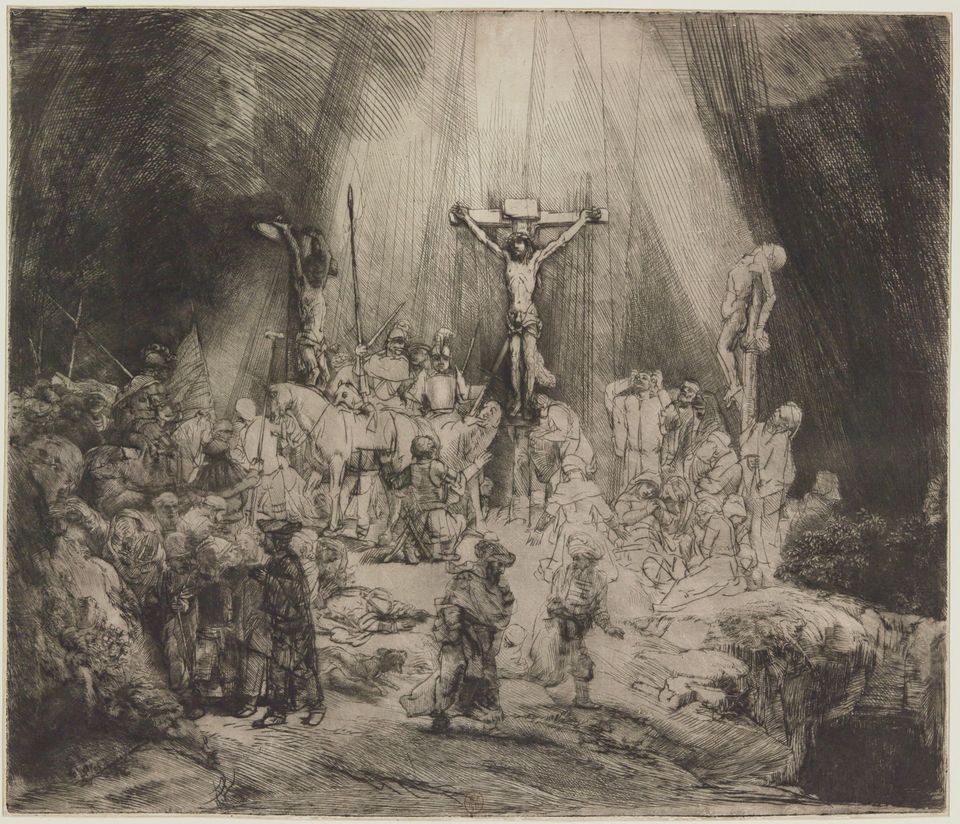

“Rembrandt intentionally made rarities for his admiring collectors who sought out rare states,†Standring said. That is, in creating his etchings, Rembrandt refined his copper-plate designs in small steps, known as “states,†that were seemingly unnecessary or at least not aligned with common practice among other artists of the the time. They generally use these early versions as a “status report†on the composition.

Because he needed the money (evidenced by his 1656 bankruptcy declaration) and knew that his collectors wanted rarities, which sold for high prices, Rembrandt purposely many more versions of his images. (About those rarities, Rembrandt was already known as a more innovative printmaker than his contemporaries, frequently experimenting with different inks and papers.)

You can read about some specific examples–such as The Jewish Bride and The Three Crosses in a little piece I wrote on this for The Art Newspaper, published in the September issue. There you’ll find some of the very impressive lenders to the exhibit as well.

The scholarship behind this exhibition, which will not travel, stems largely from Rutger’s research as co-editor of the new catalogue raisonné of Rembrandt’s etchings, which was completed in 2014.